For centuries, Pahari School painters working in the lower Himalayan hill kingdoms of northern India used a dazzling and remarkable technique to represent pieces of jewelry and other adornments in paintings. Artists active in the small court of Basohli within the Pahari region affixed parts of iridescent beetles, commonly referred to as jewel beetles, to the surface of miniature paintings to create shimmering inlays. Sparkling as they caught the light, these small pieces, made from the hardened protective forewings (or elytra) of insects, became an effective method to infuse vibrancy and life into artworks, which were often experienced within an intimate, devotional context. When held in the hands of the viewer, the shimmer produced with the slightest movement would activate the image and animate the interaction between devotee and deity.

Three paintings in The Met collection, dated between the late seventeenth century and early eighteenth century, showcase the wide range of color and optical effects that artists achieved through transforming beetle elytra into pictorial inlays. Made with opaque watercolor on paper no more than 12 inches in width, these detailed works also exemplify the bold lines, saturated colors, and imaginative style characteristic of the Basohli School of painting, which has been thoroughly described by scholars like John Guy and Jorrit Britschgi. The inlays in our study range from 5 millimeters (.2 inches) to as small as 0.7 millimeters (.03 inches) in diameter. The smallest is about half the size of a pinhead. These inlays also vary widely in color, texture, thickness, and shape. A closer look at each of these paintings offers the opportunity to investigate exactly how artists incorporated beetles into their palettes to represent the craftsmanship of the jewelry they invoked.

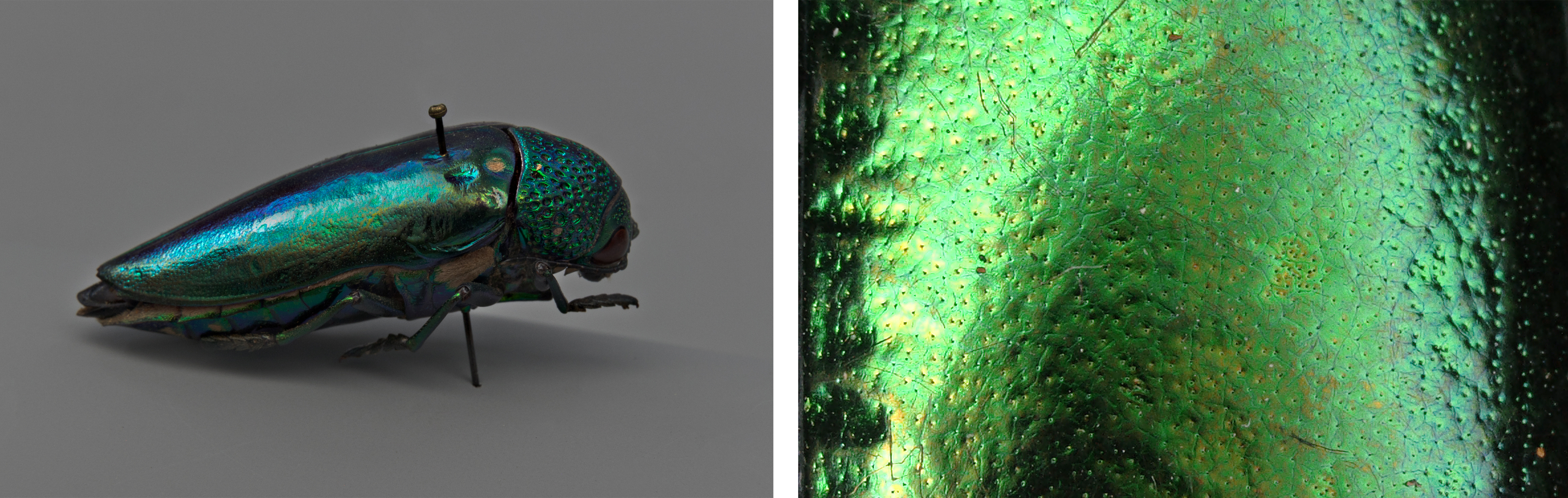

Left: Specimen identified as Sternocera aequisignata (American Museum of Natural History Coleoptera Collection). Although the most prevalent color for this species is green, it is also possible to see areas of purple, blue, and orange coloration in this image. Right: Detail of elytron (30x). The characteristic pitted pattern (or striae) on the surface of these insects is apparent with magnification.

As part of our investigation, we alternated between looking at the artworks with the naked eye, photographing the objects under different lighting conditions, and examining the works under a microscope. We also carefully studied a selection of intact jewel beetles from the Coleoptera collection at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH). Finally, we recreated period-appropriate mock-ups using commercially available elytra, which allowed us to reenact a process that accounts for some of the most distinctive features we observed in the art.

Beetles as media

Many species of iridescent beetles are native to regions in and around India. While examining beetles from the Sternocera genus in the AMNH collection, we encountered specimens originating in Calcutta, Malabar, Dindigul, Jahalpur, Sikkim, and Assam, among other regions.

The exoskeletons of iridescent beetles can produce colors that range between purple, blue, green, yellow, orange, red, and black (or an absence of color). This variety of coloration, or iridescence, is not caused by pigmentation, but rather by a wondrous phenomenon of physics that takes place when light interacts with the surface of extremely thin, multilayered films lining the outer shell of the insect.

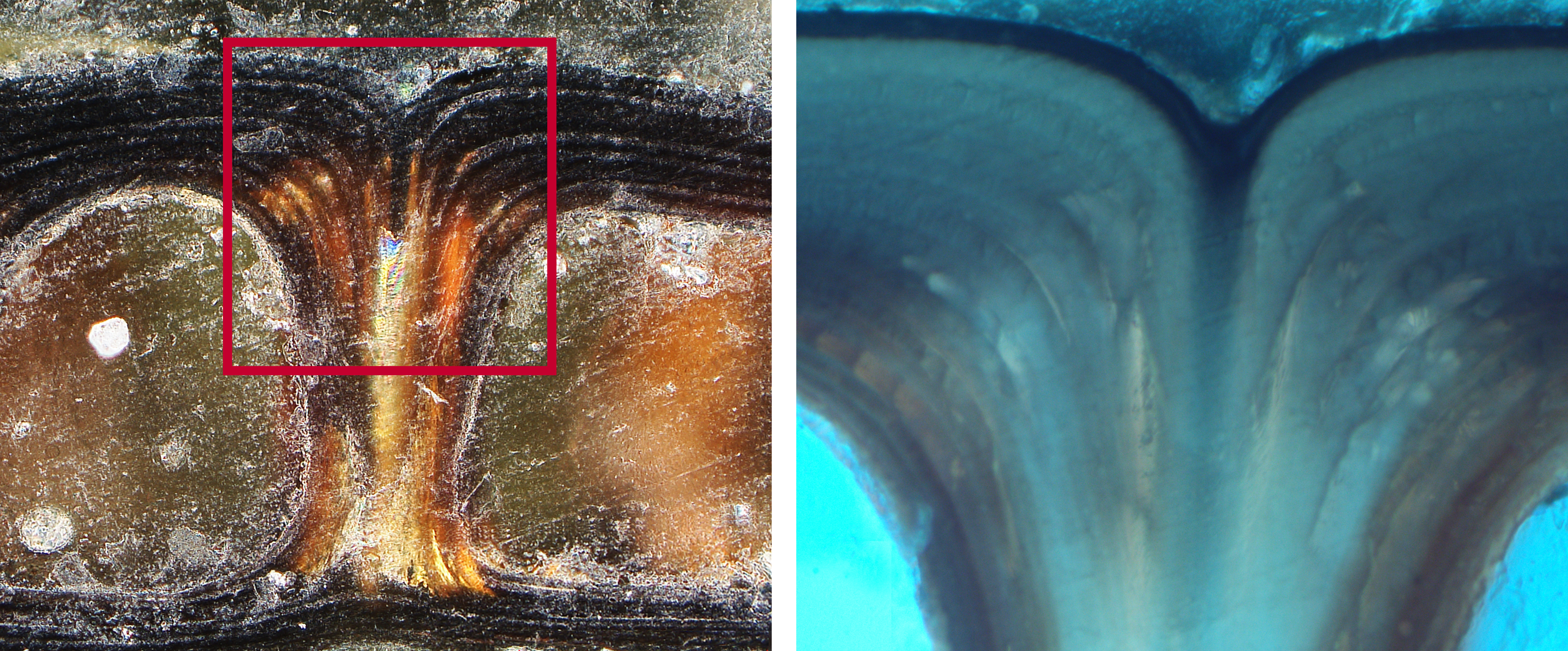

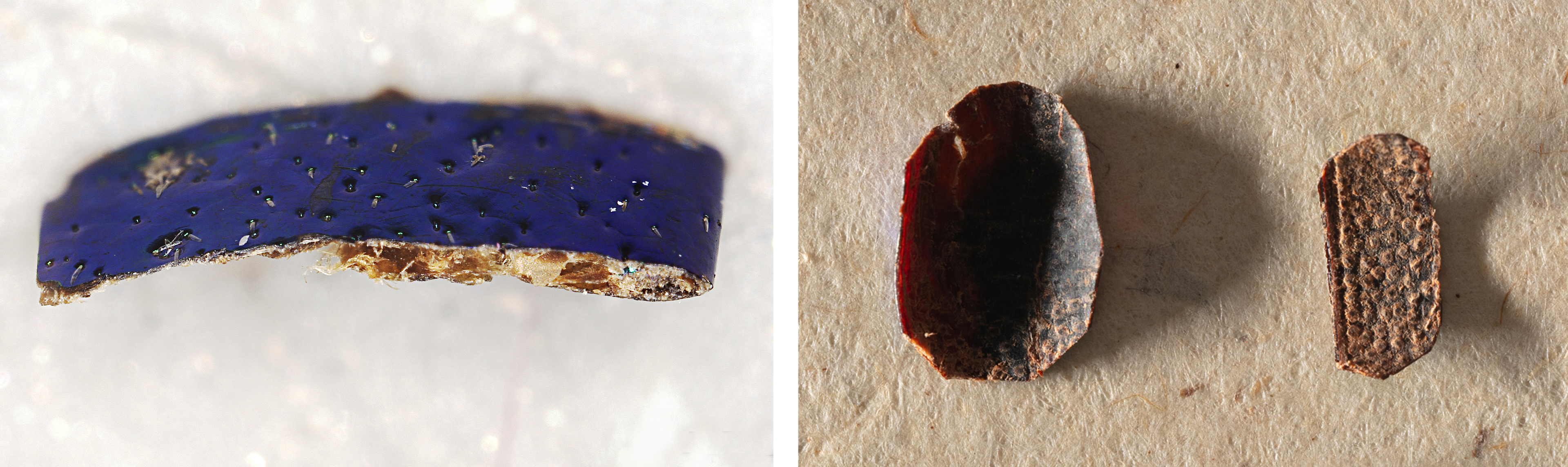

Left: Cross-section of a sample taken from a jewel beetle in the Paper Conservation Historic Materials Study Collection (40x) measuring approximately 400 microns from bottom to top, illuminated with visible light. Right: Sample illuminated with ultraviolet light at a higher magnification (100x).

The thick inner structure of elytra can be appreciated in cross-section images. Multiple layers of chitin—a tough, semi-transparent polymer that is the main component of insect coverings—are arranged in a vault-like structure capable of providing a remarkable level of protection. At the very top layer, it is possible to see that the shell has a distinct response to ultraviolet radiation, appearing dark on the right above. It is in this thin part of the shell, composed also of even thinner layers of chitin that cannot be discerned in these images, that the phenomenon of iridescence takes place.

When light enters the shell structure, it bends (refracts) and bounces (reflects) off of each layer. Light waves refracting at different angles interfere with each other and cancel or enhance specific portions of the spectrum of light. Scientists like Serge Berthier who have described the mechanism of iridescence (or interference) in beetles explain that the colors seen on their surfaces are produced by light at different wavelengths refracting by different amounts at each of these very thin layers. The specific color that one sees will depend on variables such as the index of refraction and the thickness of the layers in the shell, as well as the angle of incidence of the light source.

Basohli painters recognized this enticing attribute—as well as the durability of elytra and, likely, the stability of their color over time—and used the beetles to depict gemstones in all kinds of bejeweled elements, including earrings, finger rings, nose rings, toe rings, pendants, bracelets, headpieces, crowns, as well as embellishments to armor and warfare accoutrements.

In a sheet from the important tantric devi series, we see at center the great goddess in the form of Bhadrakali, the destroyer of the universe, standing on a slain body, her teeth bared and eyes wide. Bhadrakali is bedecked with jewelry meant to look like emeralds. Toe rings, earrings, pendants hanging around her neck: all consist of tiny fragments of jewel beetle elytra. As a devotee held the painting in their hands and moved it during the process of meditation on the great goddess, the green “gems” would have shimmered, animating the sheet and especially the goddess. By transforming beetles into media, the artist of this masterpiece added drama, presence, and animacy to a gripping devotional image.

Bhadrakali, Destroyer of the Universe, from the Tantric Devi series, ca. 1660–70. India, Himachal Pradesh, Basohli. Opaque watercolor, gold, silver, and beetle-wing cases on paper, 9 1/8 x 8 1/4 in. (23 x 21 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Howard Hodgkin Collection, Purchase, Gift of Florence and Herbert Irving, by exchange, 2022 (2022.243). Image © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

In the video below, we used Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) to simulate different light angles in order to evoke the iridescent nature of the beetle inlay, which shifts in color depending on the angle of illumination. Note the green gemstones surrounded by pearls in the furious deity’s nose ring and earring shift from green to black.

Color and texture

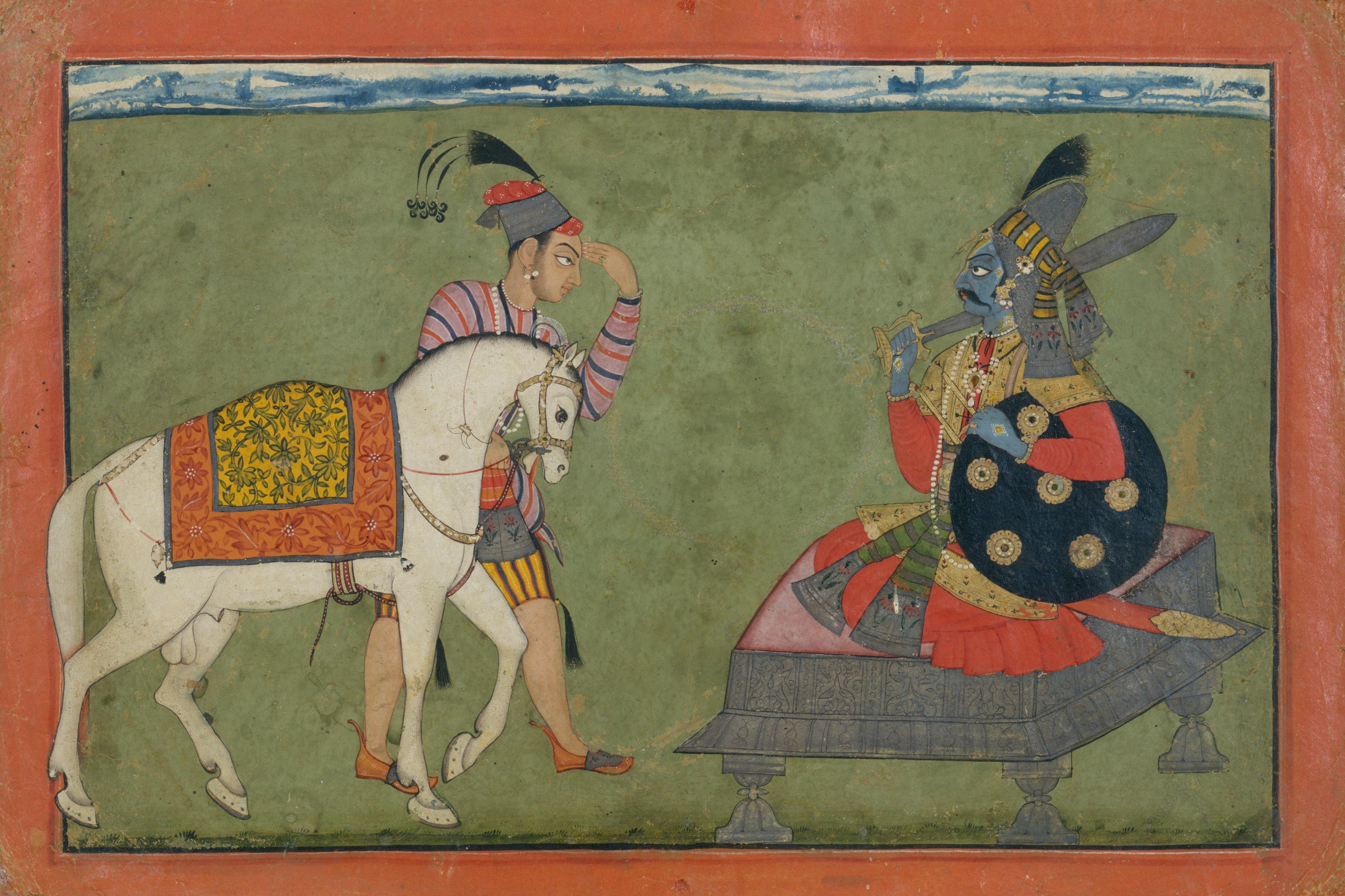

The divine figures in Kalki Avatar, the Future Incarnation of Vishnu, which depicts Vishnu as a blue-skin warrior visited by a future incarnation of himself in the form of a groom leading a white horse, bear jewelry that is painted with beetles. They are incorporated into the warrior’s armor and pendant, as well as the shield he holds, and also into the horse’s gilded bridle, where they appear as two small emeralds. These are the smallest fragments of elytra found in The Met collection, each measuring less than a millimeter in diameter.

Kalki Avatar, the Future Incarnation of Vishnu, ca. 1700–1710. India, Basohli, Jammu. Opaque watercolor, gold, silver, and beetle-wing cases on paper, 6 3/4 x 10 1/2 in. (17.1 x 26.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Cynthia Hazen Polsky, 1991 (1991.32.1)

Emeralds were a favorite gemstone of court jewelers across India, also worn by the elites in the Punjab Hills at the foot of the Himalayas where these paintings were produced. In most cases, inlays appear to have been used to render the brilliant green appearance of these valued stones, which, according to scholars Navina Haidar and Courtney Stewart, were at the time imported from places as remote as Colombia.

Although green is the prevalent color in gems painted with beetles, it is not the only color. The warrior here wears a golden embellishment on his silver helmet that, despite being damaged and partially missing, prominently displays blue and purple hues, suggesting that the gemstone he wears on his forehead is a sapphire or perhaps an amethyst.

Left: Kalki Avatar, the Future Incarnation of Vishnu (detail). Right: Magnification (90x) of Vishnu’s helmet revealing beetle-wing case.

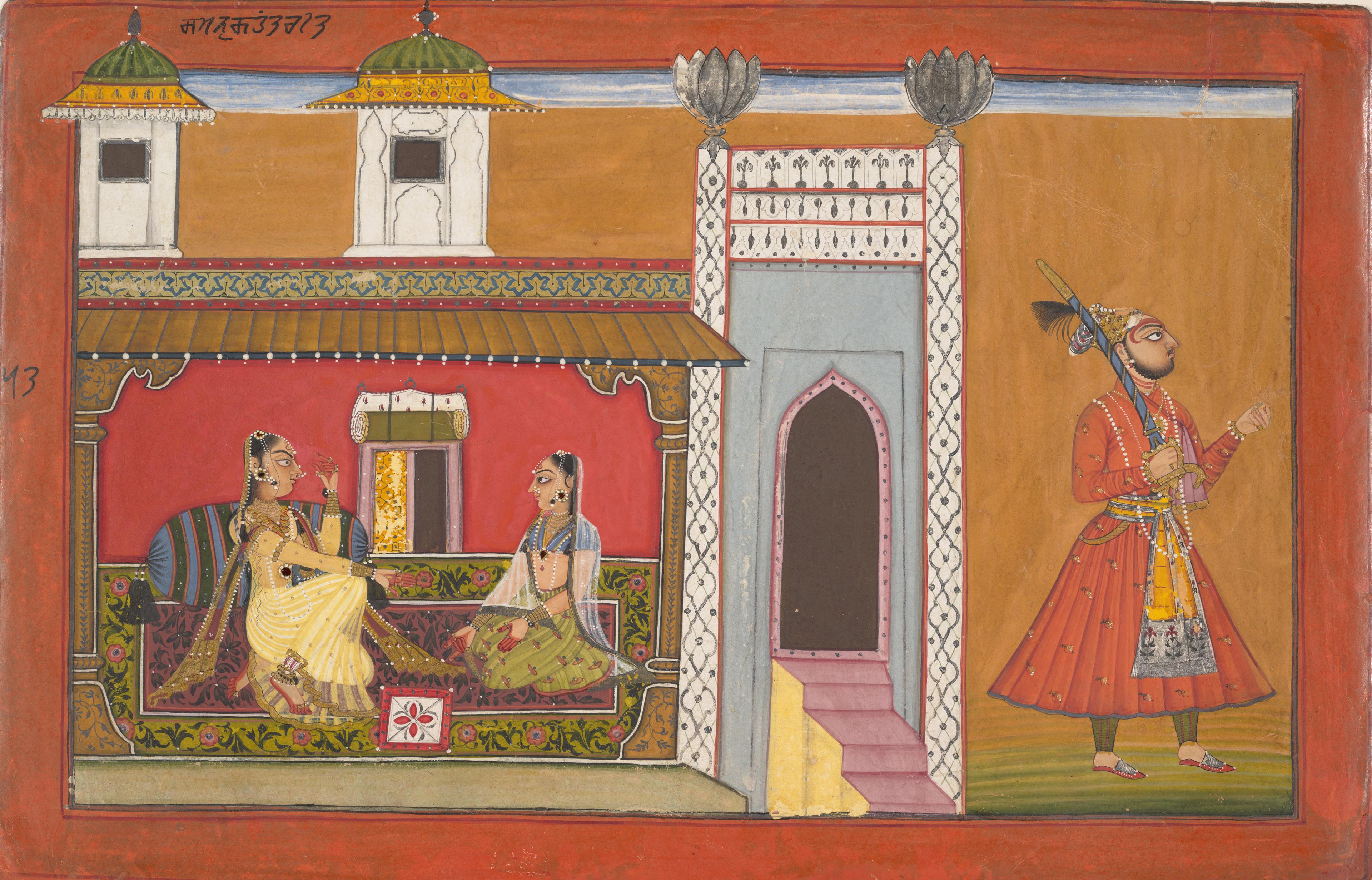

A similar case is noted in the painting A Courtesan and Her Lover Estranged by a Quarrel (1694–95), where the status of the ladies seated in their palace in the left hand side of the composition is emphasized by their opulent garments and ornaments.

Devidasa of Nurpur (active ca. 1680–1720). A Courtesan and Her Lover Estranged by a Quarrel: Page from a Rasamanjari series, 1694–95. Opaque watercolor, ink, silver, gold, and beetle-wing cases on paper, 8 5/8 x 12 3/4in. (21.9 x 32.4cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Cora Timken Burnett, 1956 (57.51.14)

The woman on the left, portrayed here soon after rejection by her princely lover, wears a red gemstone adorned with pearls on her head, suggesting the presence of a ruby.

Left: A Courtesan and Her Lover Estranged by a Quarrel (detail). Right: Right: Magnification (140x) of an unidentified reddish insect’s shell accenting the woman’s hair.

Different species of iridescent beetles display a wide range of hues and surface textures. Even within the same species, color and texture may vary. Artists must have identified not just a suitable species, but also determined which specimens and perhaps which parts of those specimens would achieve their desired effects. Furthermore, in selecting the beetles for this practice, artists may have weighed factors beyond aesthetics, such as a species’ relationship to foodways, spiritual or religious connotations, or other cultural associations.

Different species of iridescent beetles from the genus Sternocera, loaned for our study from the AMNH Coleoptera Collection. Prior literature (Rivers) states that Pahari artists favored the elytra of beetles from the genus Sternocera, like the species Sternocera aequisguata. For our study, we chose elytra of this species sourced from contemporary sellers.

Comparative examination among inlays in the artworks under the same conditions also helped identify a wide range of textures. The four inlays in the images below represent emeralds set in a shield, a bejeweled horse bridle, a pendant, and an earring, respectively. They appear to express not only several hues of green, but also very different textures. This is because the pitted patterns on the surface of the insect shell display dissimilar designs. In the first and third examples, the pitted pattern is tight; in the second and fourth below, dispersed. The presence of different textures, as with other intricate texturing techniques employed in these paintings, might simply enhance the richness and visual appeal of the work, or perhaps may be alluding to variants in gem cutting techniques.

From top: Details (90x) from the shield and the horse bridle in Kalki Avatar, the Future Incarnation of Vishnu; detail (90x) from a pendant in Bhadrakali, Destroyer of the Universe; detail (90x) from an earring in A Courtesan and Her Lover Estranged by a Quarrel

In the specimens borrowed from the AMNH, we observed color and surface texture vary across species, specimens, and even between different anatomical sections of the same insect. Artists may have chosen specific species or sections of insects’ exoskeletons to leverage these different properties and achieve different effects in finished artworks. Future research on a larger body of artworks and beetle species may reveal whether anatomy or species might help identify geography, artist, or production date.

Magnified images (100x) showing different anatomical parts for specimens from several species in the genus Sternocera. Each column represents a different specimen and each row represents a different portion of anatomy. Specimens belong to the AMNH Coleoptera Collection.

Thickness and shape

We also observed a variety of thicknesses in the paintings’ beetle-wing inlays. Some appeared very thin compared to others where more of the hardened interior structure of the elytra was visible. Some variation may be natural—different parts of the beetle shells vary not only in surface texture, but also in thickness and rigidity, and thickness may also be unique to a specimen. However, many jewel beetle inlays in the artworks studied here appear significantly thinner than any of the intact elytra we observed. We interpreted this as evidence that artists often selectively controlled the thickness by thinning the elytra, removing internal layers of material and leaving the outermost iridescent layers intact.

In this detail from Kalki Avatar, the Future Incarnation of Vishnu, the distance between the paint layer and the top of the elytra is 84.6 microns, measured using a 3-D scanning microphotograph. We cannot know exactly how thick each inlay is without a cross section, but the measurement is much smaller than the thickness of intact elytra (about 400 microns). This suggests that this inlay was thinned prior to its application.

We also determined that the thickness of elytra may sometimes play an important role in the visualization of color. An inlay that is thin enough becomes translucent, allowing light to pass through and transmit the color painted underneath if there is a small gap. In the Kalki Avatar painting, the teardrop pendant worn by the deity rests over his red coat. This inlay is extremely thin, and when catching light from different angles, it displays shades of green, orange, yellow, and dark brown, but predominantly appears red in certain lighting conditions.

Detail (30x) from Kalki Avatar, the Future Incarnation of Vishnu captured in different lighting conditions.

Thinning elytra would have required remarkable precision on the part of artists. Interior layers of elytra can be scraped away with a metal tool, but with too much pressure, one can easily puncture the iridescent surface or snap the more fragile wing into pieces. Soaking the elytra in water softens the interior layers, which become easier to peel away while the exterior remains rigid.

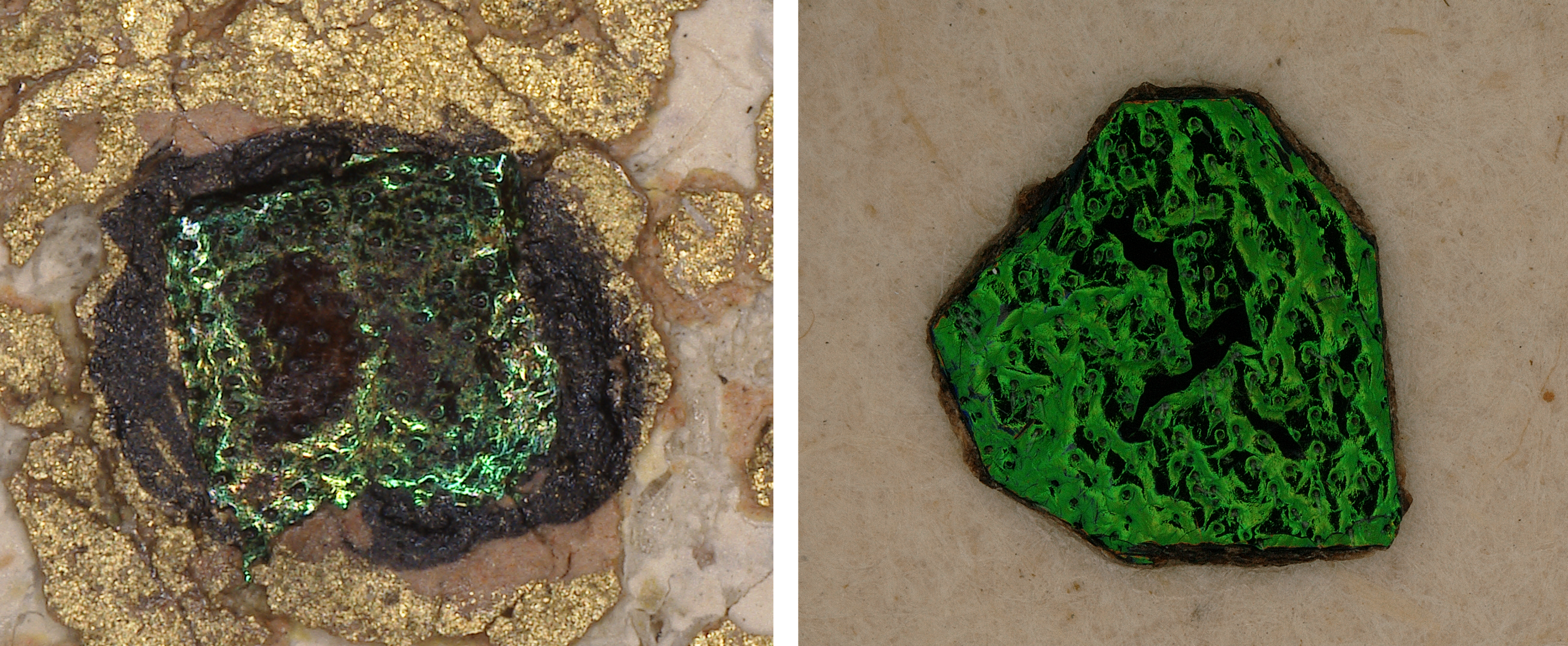

Left: Cross-section of a partially-thinned elytra fragment, illustrating the difference in thickness between thinned (left half) and intact (right half) elytra. Right: Sections of elytra that have been thinned and curled are seen here showing the inner side.

The thinning of the elytra may contribute to the appearance of distinctively non-iridescent dark spots in some inlays, shown at left below. In our initial observations, these dark spots appeared to be the result of a disturbance of the outer surface, possibly an unintended consequence of the transformation of media over time or the effect of polishing the painted surfaces, a common practice in Indian miniature painting. But we could not replicate this effect by abrading the elytra samples. Polishing the exterior of our elytra mock-ups created a disturbance of the iridescence, but the visual effect was very different from what can be seen in the artworks. We concluded that these non-iridescent spots were not the result of paintings having been abraded or polished after the application of the inlay, and we speculate that it might instead be connected with the manipulation of the inner part of the elytra. These observations also seem to confirm that the application of the beetle inlays took place in the end stages of the painting process, after the paint layers had been polished.

Left: Detail (90x) from Kalki Avatar, the Future Incarnation of Vishnu showing dark spot. Right: Mockup (90x) that was polished against a marble slab.

Once artists had achieved the desired thickness, they would cut the elytra into any number of different shapes: triangles, rectangles, ovals, circles, diamonds, tear drops—mimicking the specific profiles of different types of jewelry. In the painting of Bhadrakali, we can see a toe ring inlay cut into an elongated edge to indicate foreshortening, a device that adds perspective to the rendering of the figure.

Details from Bhadrakali, Destroyer of the Universe at two different magnifications. The square on the left image corresponds to the enlarged image on the right (100x).

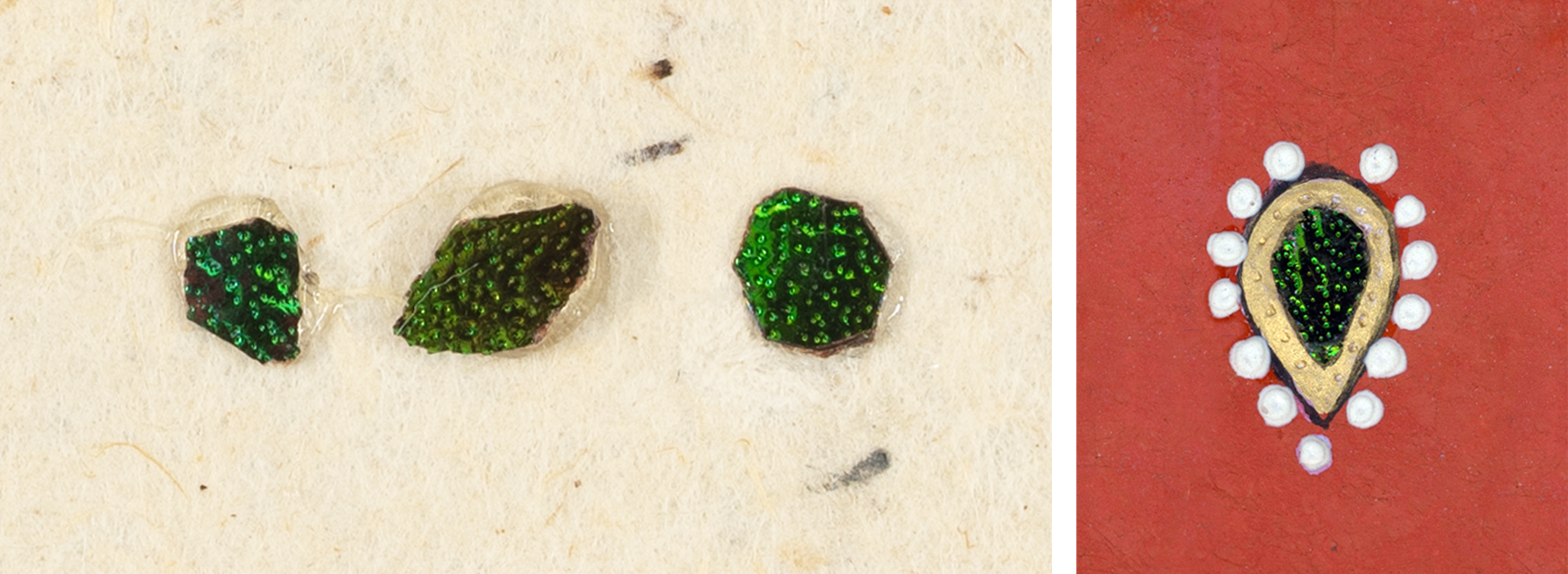

Scholars have asserted that a blade would have been used for this process, and through testing different tools—scissors, a blunt edge, a scalpel, and a blade—we found that indeed a sharp blade most closely replicated the free edges we observed. From one elytron we were able to produce approximately ten fragments. The shaped fragments were then attached to the surface of the painted paper using an adhesive.

Left: Recreated inlays thinned to different thicknesses and cut into different shapes using a thick blade (30x). Right: Inlay technique recreation with period-appropriate materials, including vermillion opaque watercolor, shell gold, and pearls painted with white pigments, outlined with black ink (30x).

Finally the inlays were finished with opaque watercolor and shell gold (a paint made from powderized gold leaves), often embellished with punchwork, a technique locally known as suikari, and surrounded by pearls portrayed with white watercolor. In our recreations, we found that the surfaces of elytra interact poorly with watercolor—they repel water such that the paint beads and resists forming a smooth line. This quality explains the uneven edges of paint bordering many inlays in paintings, despite the clear attention to detail and finesse in other areas of the same work.

Beetles as jewelry

Artists applied a remarkable level of discernment and finesse to create very refined pictorial effects in these paintings. The care lavished on the inlaid gems reflected the preciousness and experiences of the objects they referenced. In most examples, the inlays are paired in the paintings with gold and raised dots of white paint. These painterly illustrations mirror a combination of materials regularly found in actual jewelry, such as gems, gold, and pearls. Beetle elytra themselves were also used in real jewelry and other adornment for centuries in India outside the Pahari region.

Left: Detail from Bhadrakali, Destroyer of the Universe. Right: Necklace (detail, 30x), 18th–19th century. Attributed to India, Punjab or Rajasthan. Gold, diamonds, colorless sapphires, rubies, imitation emeralds (colorless rock crystal over green foil), and pearls. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, John Stewart Kennedy Fund, 1915 (15.95.77)

The inlays are sometimes level with the painting, but other times they are cambered and elevated, bulging above a flat, colored surface. Frequently, they are set inside areas of raised gold, suggesting distinct jewelry-making methods. A style often conjured in these Basohli paintings is the quintessential Indian gem setting technique known as kundan. In kundan, the gems are not held by prongs or other such elements. Instead, they are set inside patterns of gold foil filled with lac, like in the example on the right above.

In the Bhadrakali detail on the left above, the artist is using the inlay technique to emulate an earring with two emeralds. The top inlay is cambered and round, encircled in raised opaque watercolor that partially covers the edges, perhaps alluding to the kundan setting technique. The bottom inlay represents a teardrop emerald hanging from what appears to be a golden hook and eye clasp and a pearl drop.

Next steps

The examination of the details in Bhadrakali, Destroyer of the Universe, A Courtesan and Her Lover Estranged by a Quarrel, and Kalki Avatar, the Future Incarnation of Vishnu, suggests that the artists who produced these sophisticated paintings understood the complex phenomenon of light interference in beetles and were able to control it to produce very specific jewel-like effects.

We hope that this examination will encourage a more thorough characterization and understanding of similar works. The creation of a database of reference images of artworks and specimens could help determine whether the comparative analysis of visual features may provide a noninvasive means of identifying which species were used in artworks or specifying with more precision the date and place of production for artworks. Future studies will cover the identification of materials related to the inlay technique, including adhesives and opaque paints employed to render other components of the jewel elements, such as raised areas around the inlays and pearls.

The authors wish to gratefully acknowledge collaboration with and support from Tina Hagelskamp, Anne Grady, Lee Herman, Yana van Dyke, Hideyuki Masui from Hirox, Maati McKinney, Alicia McGeachy, Laura Margaret Ramsey, and Anna Serotta.