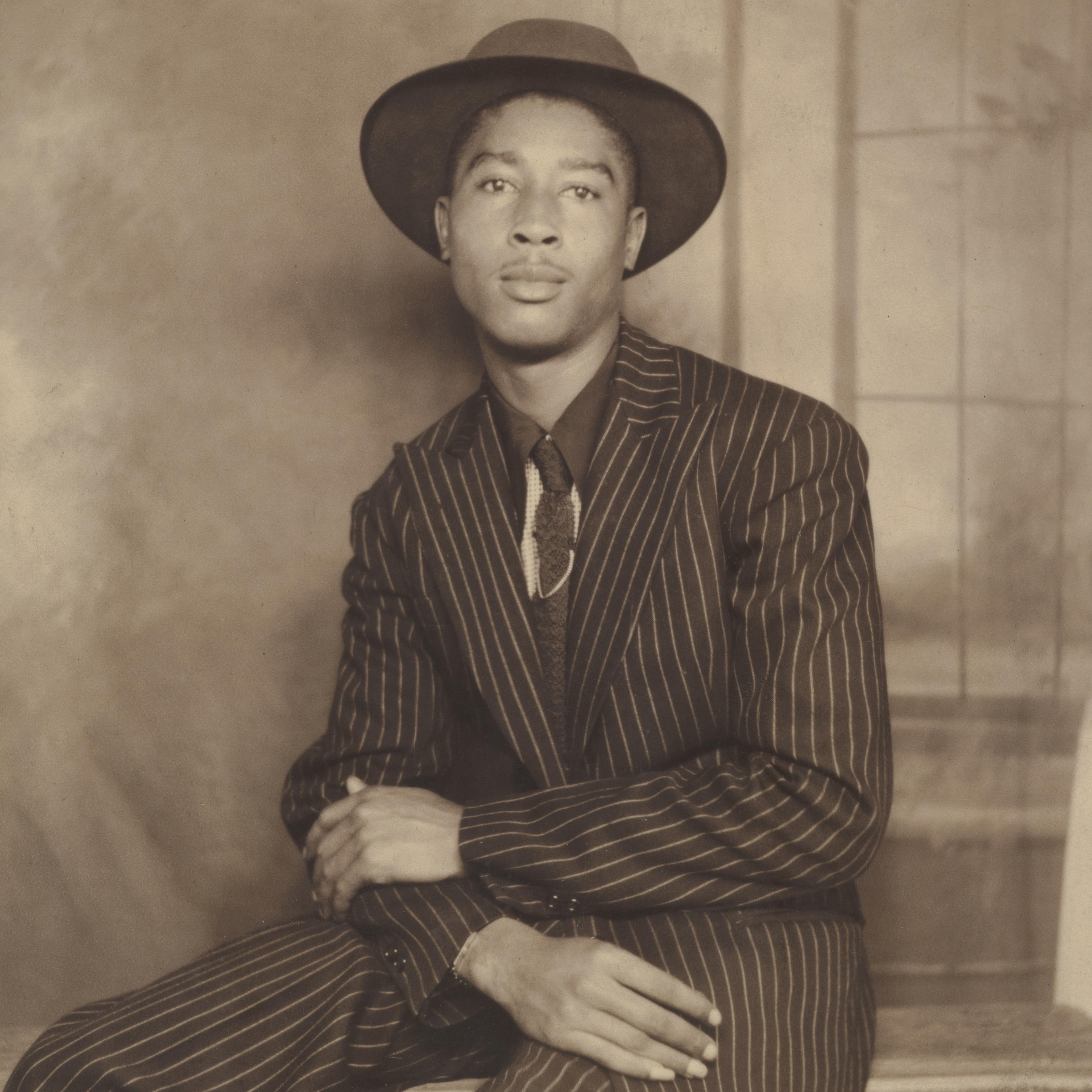

In 1789 Olaudah Equiano, who was also known as Gustavus Vassa, published a memoir that recounted his remarkable life. Enslaved in West Africa at the age of eleven, he was transported to the Caribbean and eventually to colonial Virginia, where a British naval captain bought him. He sailed on British warships for a number of years until he was again sold, this time to a merchant trading sugar and slaves between the American South and the Caribbean. Equiano’s travels taught him the value of letters and numbers; he also knew his own worth as an experienced, literate sailor who was well versed in the merchants’ trade. Equiano began to buy, sell, and trade goods on his own in the hope of saving money to purchase his freedom. When he had assembled nearly all of the funds and emancipation appeared certain, he explains in his autobiography, “I laid out above eight pounds of my money for a suit of superfine clothes to dance with at my freedom.” For Equiano, a “suit of superfine clothes” would be made from finely woven wool, an expensive luxury item, and it would be a manifestation of his newfound ability to define his future self. To procure and wear this particular form of dress represented liberation for him—a decisive and poignant moment of literal and metaphorical self-fashioning.

Daniel Orme (British, 1766–1837), after a composition by William Denton (British, active 1792–95). Frontispiece to The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African. Written by Himself, 1789. Stipple engraving, 6 1/8 in. x 3 3/4 in. (15.6 x 9.5 cm). British Library, London (1489.g.50)

In the 1780s, men who paid distinct and sometimes excessive attention to dress were known as dandies. The Oxford English Dictionary defines the figure from this time as one who “studies above everything else to dress elegantly and fashionably.” Historical manifestations of dandyism range from absolute precision in dress and tailoring to flamboyance and fabulousness in dress and style. Whether a dandy is subtle or spectacular, we recognize and respect the deliberateness of the dress, the self-conscious display, the reach for tailored perfection, and the sometimes subversive self-expression. Dandyism can seem frivolous, but it often poses a challenge to or a transcendence of social and cultural hierarchies. When Equiano imagined his superfine suit, or commissioned a portrait of himself beautifully clad for the frontispiece of his memoir, he participated in dandyism, using fine or fancy clothing as part of a repertoire of self-definition.

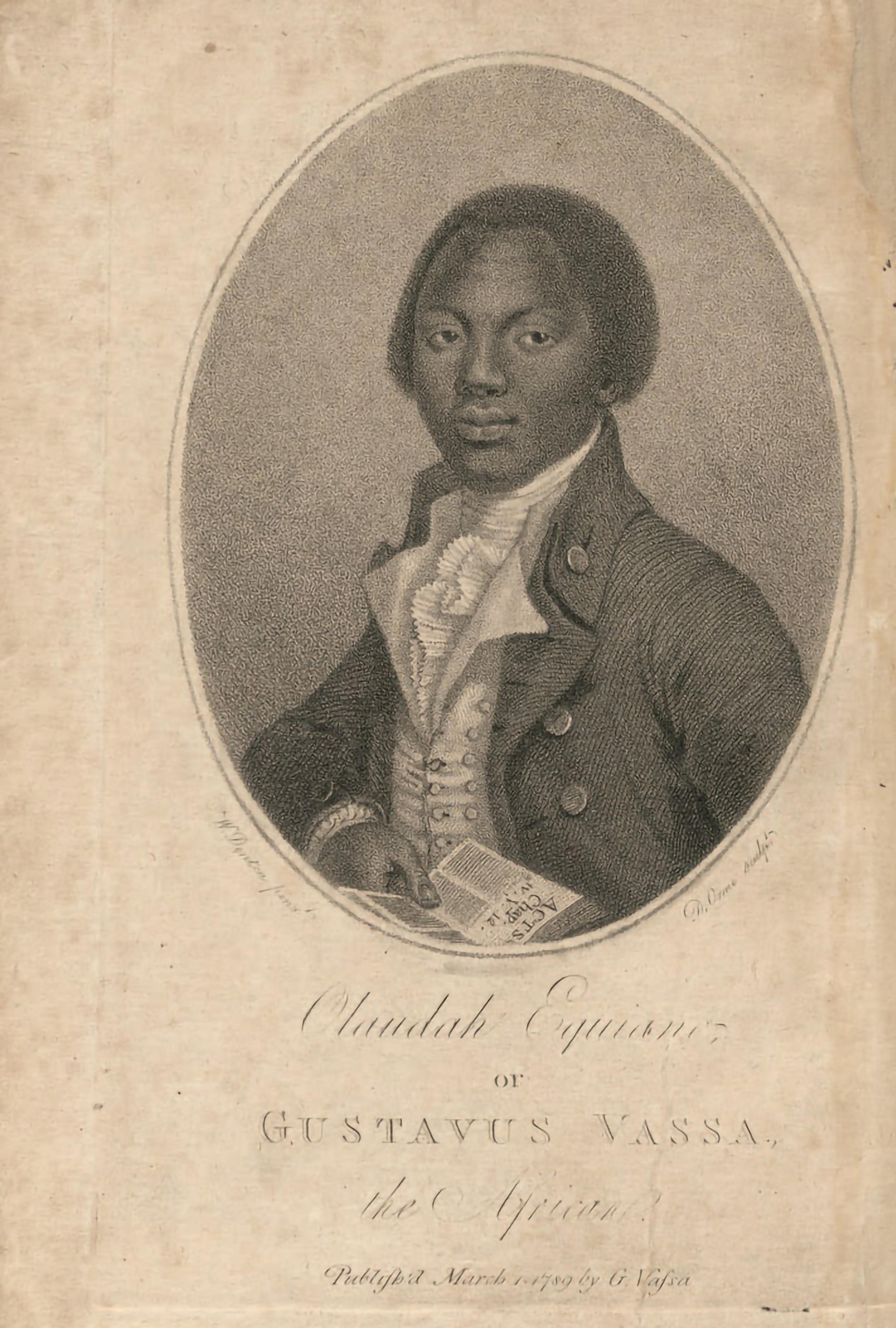

How and when does Black dandyism begin, and what are its multiple meanings? What other enslaved and free people experienced and manipulated the power of clothing and dress to define a social position or enhance cultural and political possibility? In the eighteenth century, dandyism was imposed on and used by Black people swept up into the political realities of the time—namely, the slave trade, colonization, imperialism, revolution, and liberation. Dandified servants, then known as “luxury slaves,” were used as figures of conspicuous consumption, their finery evidence of symbolic rather than manual labor. Others, like Equiano, might not have been dressed in this way, but through their necessary observation of the social world around them—the appreciation of which was central to their survival—they understood where and when “fancy” dress mattered and how it could signify as liberatory and oppressive. Part of the facility for reading and comprehending these codes and values had to do with West African traditions of dress and display, especially as Western and African cultures and styles confronted each other on the Atlantic coast. Fine textiles were used as currency and a means of exchange: a bolt of fabric could pay for a person; African merchants adorned themselves in abaya-like garments and tophats. Those situated in the Atlantic diaspora had indigenous traditions that strategically utilized fancy dress; they immediately understood and redeployed the effects of dressing elegantly and fashionably and its relationship to race and power.

Left: Untitled [Portrait of four young men], ca. 1890. Possibly Congolese or Angolan. Photo courtesy of Michael Graham-Stewart. Right: Neils Walwin Holm. Untitled [Portrait of two men], 1890–92. © Musée du Quai Branly–Jacques Chirac, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, New York

Thus, Black dandyism is a sartorial style that asks questions about identity, representation, and mobility in relation to race, class, gender, sexuality, and power. Superfine: Tailoring Black Style (2025) explores dandyism as, among many other things, a dialectic—a movement between being dandified and taking on dandyism as a means of self-fashioning. In Superfine, dandyism is both an aesthetic and politics, a pronouncement and provocation.

When Equiano danced in his new superfine suit at his freedom, he broadcast the importance and profundity of the joy of self-possession and agency. Although he knew the word superfine in relation to the quality of a fabric, over two hundred and fifty years later we also understand it as a particular mood and attitude associated with feeling especially good—fantastic even—in one’s own body and in clothes that profoundly express the self. This feeling is often so evident that it is instantly recognized by others, who will announce—with admiration and enthusiasm on seeing you in that suit, with that hat, as you strut—that you are superfine. Wearing superfine and being superfine are, in many ways, the subject of this exhibition. The separateness, distinction, and movement between these two states of being in the African diaspora from the 1780s to the present animate this show. Having bought his freedom and wearing his suit, Equiano recounts, “In short, the fair as well as the black people immediately styled me by a new appellation, to me the most desirable in the world, which was freeman; and at the dances I gave, my Georgia super-fine blue clothes made no indifferent appearance, I thought.”

The exhibition is inspired by my book Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity, a cultural history of the phenomenon published in 2009. This literary and visual study primarily examines Black dandyism from Enlightenment England to contemporary New York and London. It chronicles how the representation of Black people transformed from them being dandified, costumed, and dressed luxury slaves during enslavement, colonization, and imperialism to self-fashioning individuals who use fashion, dress, and style to assert their humanity and agency. As such, Black dandies create and experience moments of mobility and transcendence in the personal and the political realms, critically questioning and redeploying their relationship to consumption and self-regard. To discern the distinctive nature and power of Black dandyism as a tool of self-definition, this analysis relies on what literary scholars call “close reading” techniques of the cultural and historical contexts of various literary, visual, and filmic texts.

Dandyism is both an aesthetic and politics, a pronouncement and provocation.

Dandyism is identified as a phenomenon that has particular meaning in times of political, social, and cultural transition—say, for example, during the abolition of slavery and the subsequent emancipation, the Great Migration, urbanization, and decolonization. In these moments, changing clothes and “stylin’ out” announces and explores new identities; Black folks do this for themselves, their communities, and the societies in which they live. In this setting, dandyism is an interrogative practice: a Black person in fancy dress—exquisitely styled, accessorized, and coiffed—calls into question what we think we know about race, gender, class, and sexuality. Black dandies press and propel, serving as agents of what Iké Udé, the aesthete-artist whose self-portrait is featured on the cover of Slaves to Fashion, calls “the luxurious deliberation of intelligence in the face of boundaries” in Kobena Mercer’s essay “Post-Colonial Flaneur.”

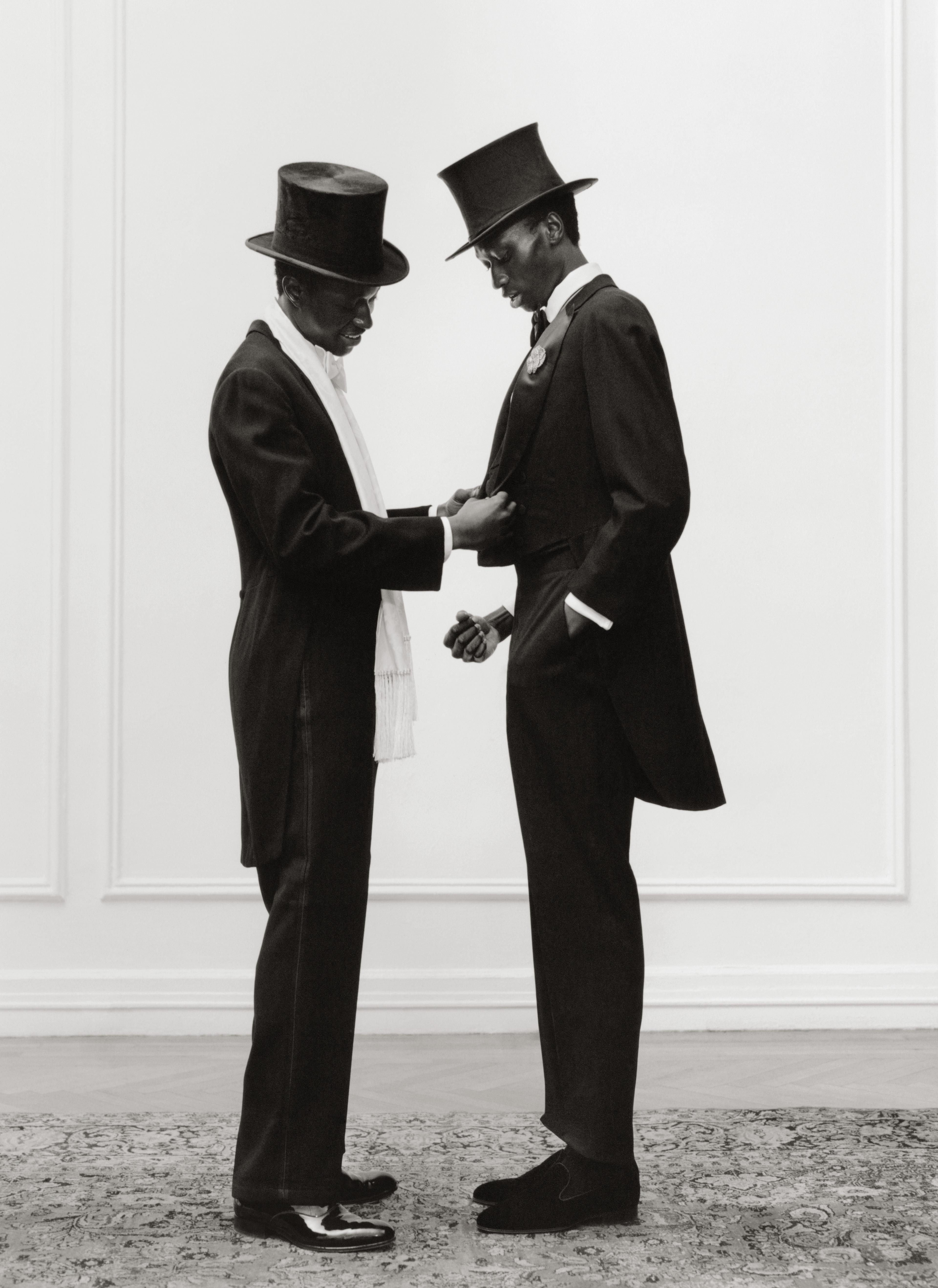

Tyler Mitchell (American, b. 1995). True Care. © Tyler Mitchell. Photo courtesy of Tyler Mitchell

In the last twenty-five years, the study and exhibition of Black fashion and dress cultures have exploded, changing and growing significantly along the way. I hoped a book on Black dandyism would be of interest to scholars in African American studies and of the Black diaspora. But amazingly it also had an impact on fashion studies. Written at the same time as the appearance of new scholarship on the history of slavery and emancipation—when the varying archives of Black life were being theorized and explored, when race was being seen as both a materiality and a performance, when identities and disciplines were being queered—Slaves to Fashion captures a moment of inflection for Black studies and fashion studies. In the wake of Thelma Golden’s groundbreaking 1995 exhibition Black Male and a new wave of Black dandyism that could be seen in popular culture and, more importantly, on the streets, Black dandy style came into vogue just as I was writing about it.

While Superfine is clearly related to Slaves to Fashion, they are not the same. As a guest curator at The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute, I have had to think about the relationship between fashion, dress, style, and costume, as these concepts are defined differently and communicate variously depending on how or where they are referenced inside or outside of the academy, the museum, the media, and the fashion industry. I have had to translate the book from text and image to garment and object—from an interdisciplinary cultural analysis of Black dandyism that privileges literature and visual culture to a transtemporal, multigeneric exploration of Black dandyism that centers fashion objects. Slaves to Fashion is about Black self-fashioning—the power of clothing and dress as a tool and strategy for identity formation—but it is not about Fashion with a capital F and all that word seems to imply: fashion design, designers in the industry, or the business of fashion.

What makes Slaves to Fashion possible as an inspiration for a Costume Institute exhibition is its focus on “high style.” The Costume Institute collection includes historical and contemporary menswear illustrative of this sensibility and of dandyism. Even though the vast majority of the menswear collection was not worn by or created by people of African descent, it offers a base and background on-site for imagining what this exhibition can look like.

Tyler Mitchell (American, b. 1995). The Group Portrait (2024). © Tyler Mitchell. Photo courtesy of Tyler Mitchell

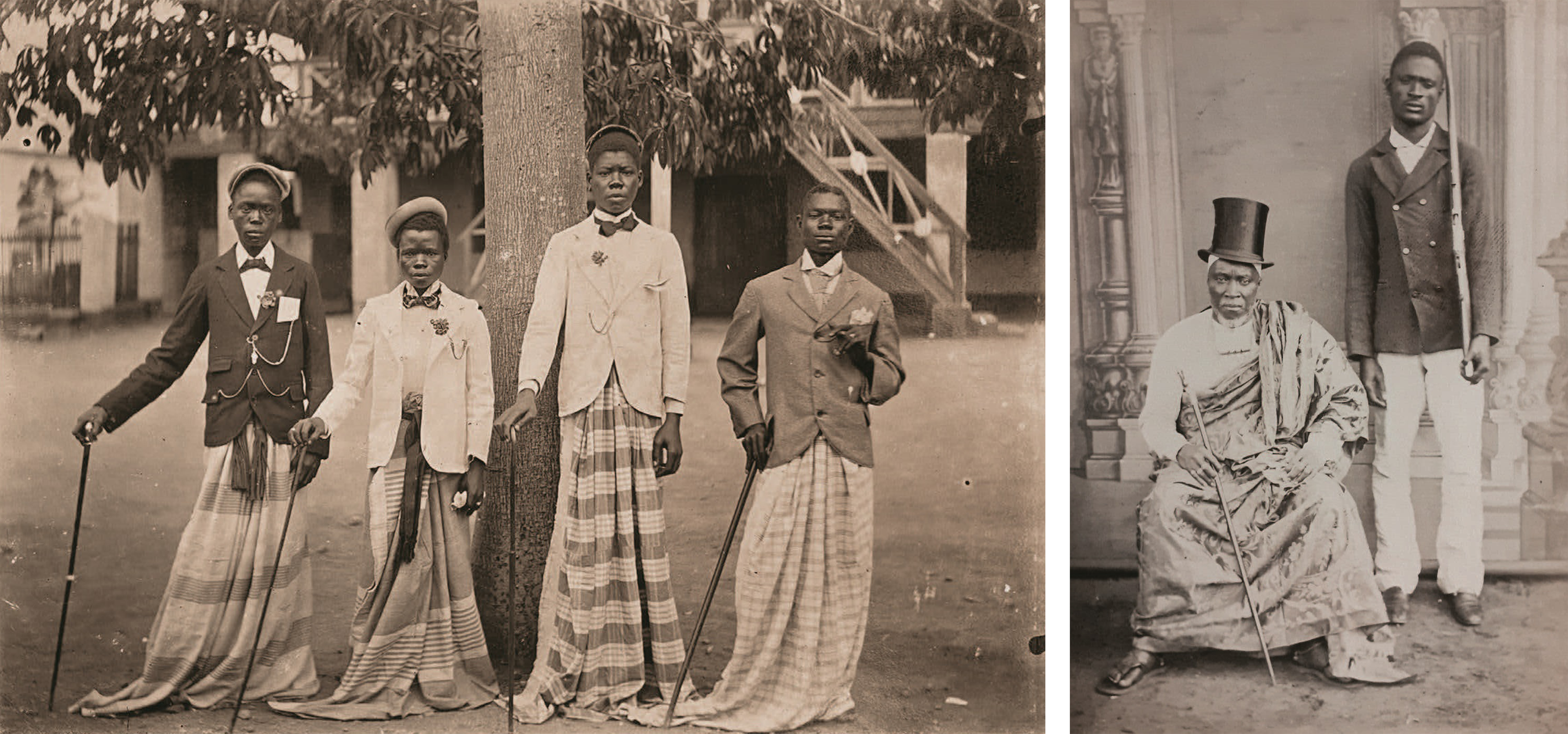

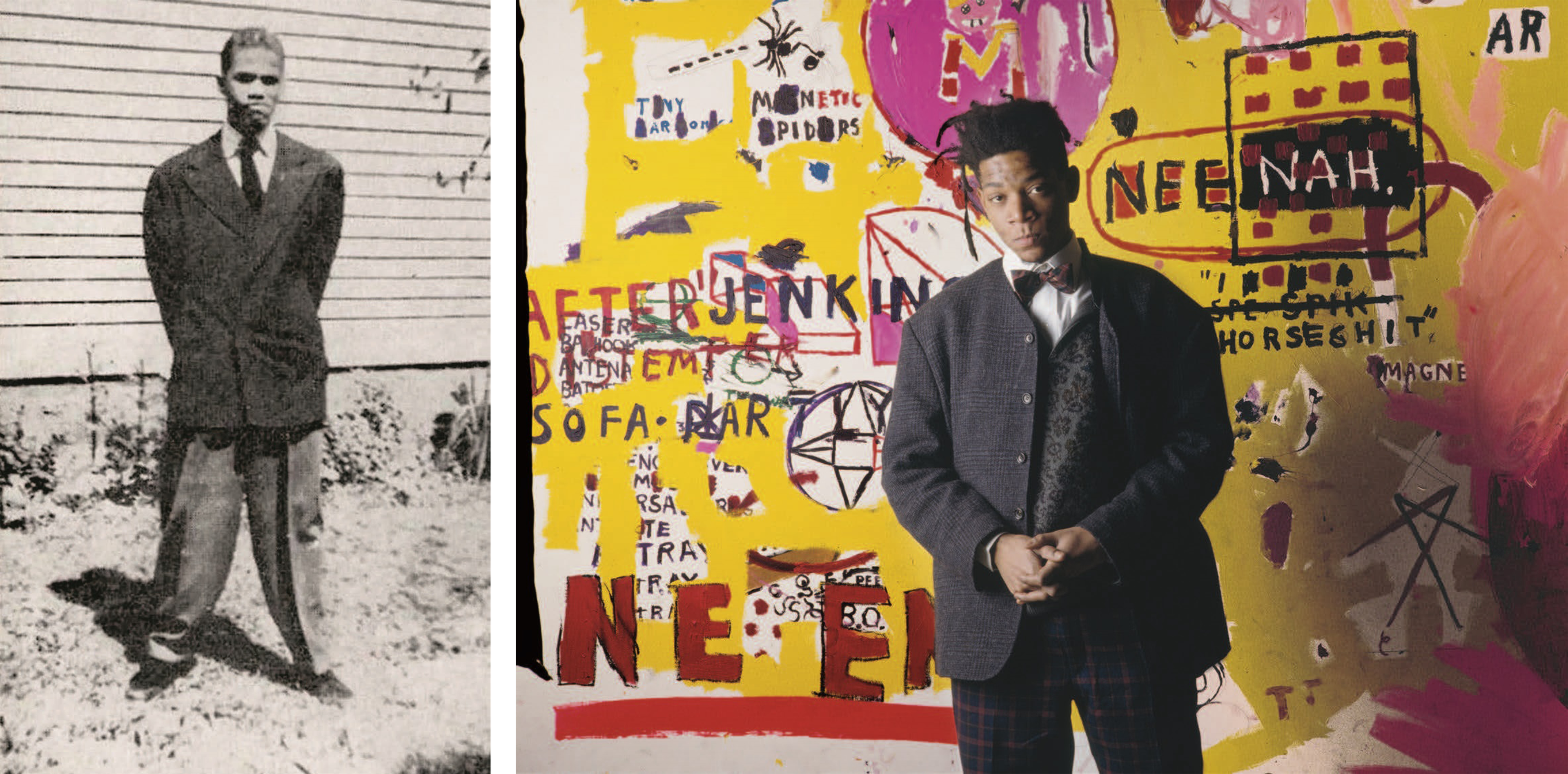

Being tasked with thinking like a curator has allowed me to transform and expand the narrative of my original analysis. For Slaves to Fashion, I had followed the written, visual, and performance-based archive. Parsing a single footnote about W. E. B. Du Bois’s dandyism (and his fury at being referenced in this way) sent me backward in time in search of understanding a dandy’s social, political, and cultural critique as well as the figure’s specific resonances and tensions within Black history and culture. At the time, my references for dandyism were not only straight out of my childhood in the 1970s and '80s but also literary: I recalled my father and my uncles in three-piece plaid suits, accessorized with cocked hats and heeled shoes in contrasting leather when the occasion called for it (and sometimes when it did not). I observed my cousins building entire outfits around gold chains, links both curbed and roped, repping hip-hop styles just emerging from New York. I had read Regency drama, Oscar Wilde, and modernist fiction, all of which included dandy figures for whom the sartorial practice was a gesture at control or a strategy of rebellious, subversive distinction in a rapidly changing modern world. I had also pored over The Autobiography of Malcolm X (1965), in which a young Malcolm Little, preparing himself for the Lindy Hop dance floor and a career as a hustler, glories in his first zoot suit. I had ripped from a newspaper article and hung on my teenage bedroom wall a photograph of a young Jean-Michel Basquiat, cool and regal in a combination of formal suiting and streetwear.

Left: Untitled [Malcolm Little, 15], ca. 1940. Published in The Saturday Evening Post, September 12, 1964. Right: Julio Donoso (Chilean, active 1980s). American painter Jean-Michel Basquiat, 1988. Photo courtesy of Getty Images

Understanding the tension and relation between these things—what it means when a dandy is racialized and when a Black person uses dandyism as a tool or strategy—sent me back to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, to moments of contact between Africans and Europeans, when clothing, dress, and even cloth became noticeable vessels of power. I saw Africans and then men of African descent thrust into a burgeoning diaspora negotiating their identities and possibilities with the clothes on their backs. Men were most visible in this archive, as they were the most chronicled in travel narratives and some of the first authors of memoirs detailing their enslavement and actual and metaphorical liberation; their expanded mobility, when compared to that of women, garnered more notice and helped enter their experiences into the historical record. I could trace their use of dandyism from the eighteenth century to the present, in their own words and others’ words, in histories of the stage and theatrical productions, in fiction, prints, caricature, and painting, in film and photography.

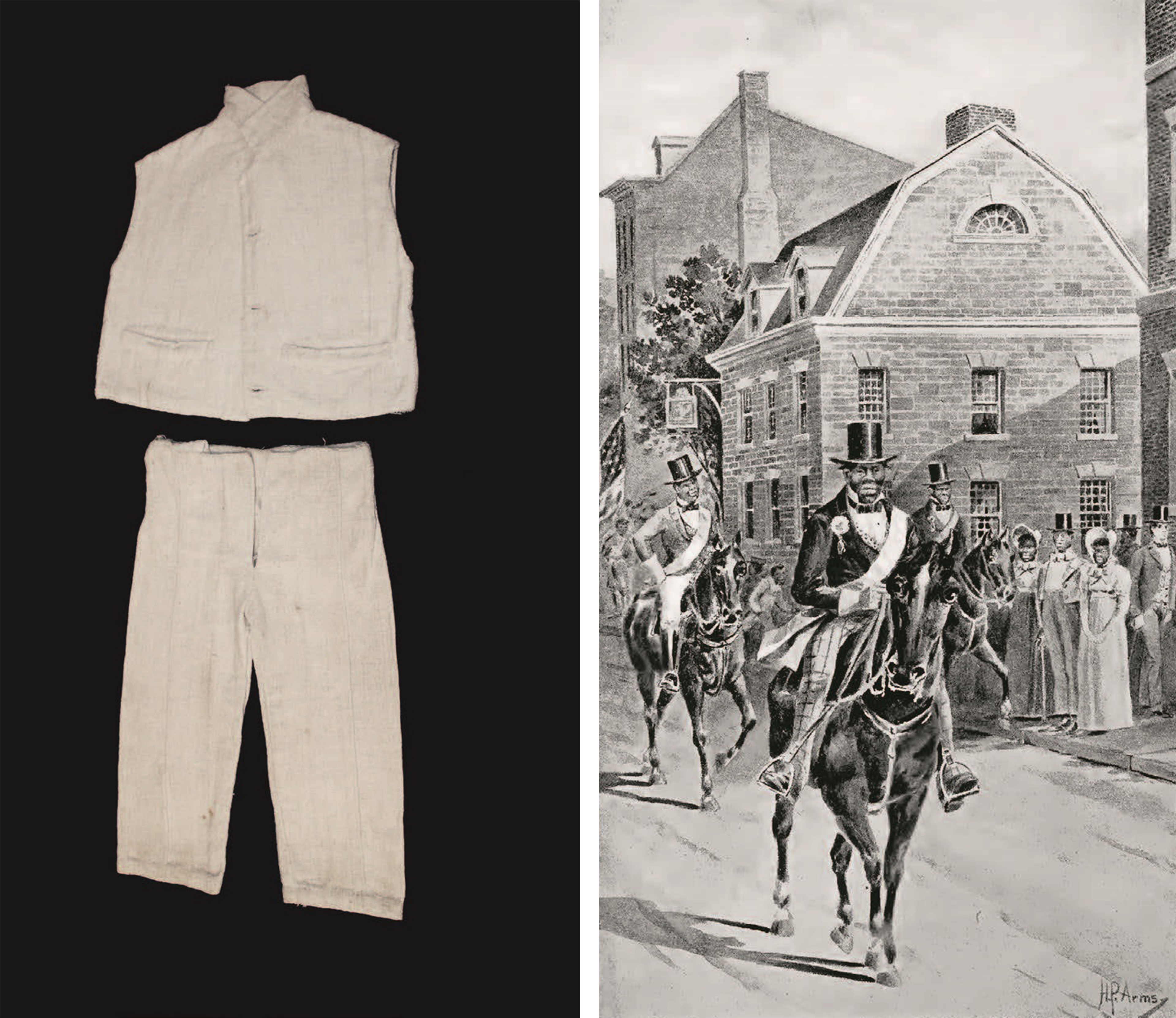

While the textual archive of Black self-fashioning might go back to the eighteenth century—or even earlier, if one knows where and how to look—the material archive is much more limited. Clothing worn (or made) by enslaved individuals, regardless of whether they toiled in domestic settings or in the fields for Southern planters, Northern merchants, royalty, or aristocracy in the Americas or Europe, was overwhelmingly neither valued nor preserved. Standard-issue clothing was often made of homespun, coarse fabric like osnaburg, hemp, flax, or cotton, which disintegrates with use and over time, as Katherine Gruber explains in “Clothing and Adornment of Enslaved People in Virginia.” While I knew of festivals such as Jonkonnu, Negro Election Day, and Pinkster, in which captive people paraded in fancy dress borrowed or inherited from their enslavers or that they created themselves, I did not know of any surviving garments. I was aware of the desire of many enslaved people, like Equiano, to “change clothes” at the moment of their liberation. Ads posting fugitives from slavery detail the quantity and quality of clothing that people escaped with; whole closets were carried away. And yet, very little remains.

Left: Child’s “slave cloth” sleeveless jacket and pants from Louisiana, 1850s. American. Undyed hand-spun woven cotton. Shadows-on-the-Teche, a Site of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, New Iberia, La. (NT59.67 .644 [5B]). Right: Hiram Phelps Arms (American, 1854–1925). An Election Parade of a Negro Governor. Published in volume 5, issue 6 of The Connecticut Magazine, June 1899

While this dearth was true of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the twentieth century provided a different challenge. In the early part of the twentieth century, some garments and accessories of notables like Cab Calloway and Duke Ellington were preserved as part of their estates and archives, but the attire of ordinary people who chose to dress to the nines for a night out in Harlem or a wedding or funeral on Chicago’s South Side was largely not extant. To reimagine the book as an exhibition, I would have to think across disciplines and genres. We could fill in the gaps in fashion history as I had done in my own research, with paintings, prints, and decorative arts depicting the dandified and self-fashioning dandies themselves.

Left: Piper & Piper Custom Tailors (American, active 1920s–70s) and Scotty Piper (American, 1904–1987). Shoes worn by Scotty Piper, 1973. Red and black leather; buckle of gold metal. Chicago History Museum, ICHi-178231 (1975.116.2e–f). Right: Piper & Piper Custom Tailors (American, active 1920s–70s) and Scotty Piper (American, 1904–1987). Hat worn by Scotty Piper, 1973. Polychrome striped wool-polyester twill; band of gray and red silk grosgrain; pink feather. Chicago History Museum, ICHi-178215 (1975.116.2a–f)

But as a curatorial team, we would also have to locate garments and accessories worn and made by superfine folks, digging deep into the holdings of historical museums and societies such as the Historic New Orleans Collection, the Chicago History Museum, and the GLBT Historical Society in San Francisco. We would have to contact the archives of “race men” such as Douglass and Du Bois, and the estates of legends like Muhammad Ali. We would talk to tailors like James McFarland, known as “Gentleman Jim,” who was active on Harlem’s 125th Street in the 1960s and ’70s, outfitting, among many others, Ali, Jackie Robinson, and James Brown; we would call Ozwald Boateng, celebrated Savile Row-trained fashion designer, who was the first tailor to show at Paris Fashion Week. We would negotiate with private collectors of vintage and contemporary fashion and accessories on both sides of the Atlantic. We would have to think about and beyond visual culture, respecting and strategizing with the archiving and collecting practices of the community.

We would look to Grace Wales Bonner and Virgil Abloh to examine the ways in which each designer communicated their own knowledge and study of Black diasporic history writ large and small. Inspired by writers Ishmael Reed and Ben Okri as well as by outsider artist “St. James” Hampton, Wales Bonner’s autumn/winter 2019–20 collection “Mumbo Jumbo” focused on magic and mysticism within the Black Atlantic. As Reed himself says of Wales Bonner, “Like Charlie Parker who obeyed the key signatures required by the songs he played, but did something different when improvising the chords attached to these songs, Grace Wales Bonner looks backward to traditional European modes of fashion, but comes up with original designs[. …] She’s an artist.”

Left: Marcus Tondo (German, b. 1974). [Runway image of Look 14 from Wales Bonner’s “Ezekiel” collection by Grace Wales Bonner], 2016. Right: Wales Bonner (British, since 2014). Grace Wales Bonner. Ensemble, autumn/winter 2020–21. Suit of two-tone brown wool tweed; turtleneck sweater of light blue wool ribbed knit. Photos courtesy of Wales Bonner

The show notes implore, “Honour our ancestors. Honour the lineage.” Wales Bonner does so here and in all of her collections; although her own Jamaican and British heritage often functions as an influence, her design collections establish her as a citizen of an Afro-cosmopolitan, Afro-futurist world. As described in the show notes for the spring/summer 2019 “Ezekiel” collection, looks in this world include “restrained mohair suits in ebony […], with brilliant white starched shirting” as well as “floating spirituals in ivory frock coats, [and] romantic silk shirt dresses.” Her autumn/winter 2020–21 “Lover’s Rock” collection featured what the show notes call “tropes of the British wardrobe: Donkey jackets, repurposed 1960s Saville [sic] Row tailoring. A moleskin double-breasted blazer adorned with found buttons.” Wales Bonner’s study of life and living in the African diaspora functions as an examination and appreciation of Black fashion and style history; they are coeval and commensurate. Superfine would need to chronicle and honor this depth of knowledge and practice.

We would also foreground those working within tailoring traditions who are an indelible and profoundly important part of the history of artisanship within the community. In this exhibition, tailoring is an actual practice and a metaphor that defines Black style and stylization; the curation would have to reflect the materiality and symbolic importance of these traditions. So many tailors and designers are nurtured in families with members or even ancestors who have worked as tailors, seamstresses, quilters, menders, home sewers, and needleworkers. This knowledge and skill pass down through families and communities for reasons of both economic survival and the pleasure in and satisfaction of pushing the boundaries of style.

Frances Benjamin Johnston (American, 1864–1952). Tailor boys at work, 1899–1900. Platinum print, 7 1/2 x 9 1/2 in. (19.1 x 24 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Gift of Lincoln Kirstein (859.1965.86)

To tell this story, we would have to go back to the nineteenth century and think about what it meant for a Historically Black College and University (HBCU) like Hampton University to offer classes in tailoring to its students, training young men for a trade and an art that facilitated the respectable presentation that so many of their graduates, future representatives of the race, would covet. We would need to account for the impact the Great Migration would have on fashion and style; the growth of urban centers in the North and West created new opportunities for folks to express themselves differently for themselves and for each other on a grand and gorgeous scale. Just as Equiano danced at his freedom, new-to-the-city folks strutted too, as Toni Morrison describes in Jazz (1992), her novel set in 1920s Harlem: “Here comes the new. Look out. There goes the sad stuff. The bad stuff. The things-nobody-could-help stuff. The way everybody was then and there. Forget that. History is over, you all, and everything is ahead at last.” Tailors made the three-piece and zoot suits that these new environments demanded and required.

Nadine Ijewere (British, b. 1992). Morehouse Students Dimone Long, Jerry Yekeh, Jalen Campbell, Darian Bogie, and Model Caleb Elijah, 2021. Ralph Lauren Corporation Collection

Over the course of the twentieth century, the Black tailoring tradition seeded the eventual emergence of fashion designers like Dapper Dan, while more traditional menswear designers apprenticed with design houses, rising within their ranks before branching out on their own. Designing for Ralph Lauren, Calvin Klein, and then his own label, iconic designer Jeffrey Banks made this journey; James Jeter, the lead designer of the HBCU capsule collection for Ralph Lauren and now the label’s creative director for its Polo brand, is on a similar path.

Superfine brings all of these narratives together and organizes them as expressions of Black style through the art of dandyism. Expressions is the operative word here, as this exhibition does not seek to be definitive, even as it necessarily and joyously offers some modes in which dandyism is defined and articulated. As a conceptual inspiration for the exhibition, I looked at an essay that may not mention fashion but is nevertheless centered on critically examining and celebrating African American style.

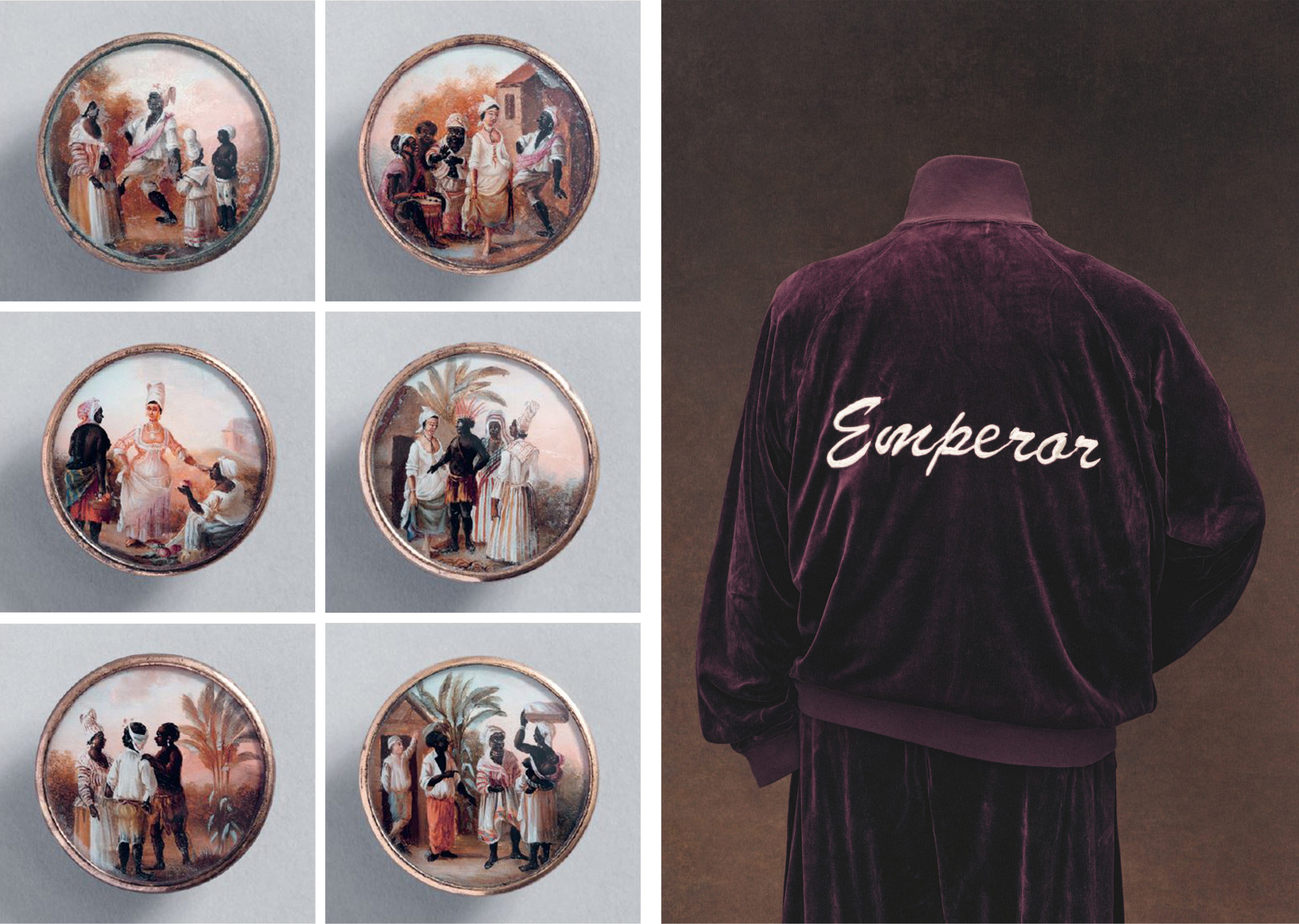

Left: Attributed to Agostino Brunias (Italian, ca. 1730–96). Buttons, late 18th century. Gouache paint on ivory verre affixed to glass with ivory backing and edged with gilt metal, 3/8 × 1 1/2 in. (1 × 3.7 cm) each. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Gift of R. Keith Kane from the Estate of Mrs. Robert B. Noyes (1949-94-1, 7–9, 12, 15). Right: Juicy Couture (American, founded 1996). Tracksuit, ca. 2004. Jacket of purple cotton-synthetic velour edged in purple cotton-synthetic ribbed knit and embroidered with ALT and Emperor in white thread; trousers of purple cotton-synthetic velour. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Alfred Z. Solomon-Janet A. Sloane Endowment Fund, 2023 (2023.791a, b)

In her “Characteristics of Negro Expression” (1934), Zora Neale Hurston identifies twelve characteristics that she believes are building blocks of Black expressive culture, the second of which is “the will to adorn,” which she discusses primarily in terms of decoration. Elaborated on as “the feeling […] that there can never be enough of beauty, let alone too much,” this desire for beauty imbues Black life with another of Hurston’s characteristics: drama. For me, the beauty (and drama) in this exhibition can be seen on many levels: in the signifyin’ and showin’ out that drives Black dandyism’s dialectic, critique, and force; in the intelligently conceived and carefully stitched and tailored garments themselves; and in the scale on which this story will be told through (occasionally unexpected) elements of style. These elements are sometimes small accessories—for example, buttons said to have been affixed to Toussaint L’Ouverture’s coat—and also whole ensembles, like André Leon Talley’s Juicy Couture tracksuits, the jackets of which have the words Emperor, Tsar, or King of the Universe embroidered on the back. In Hurston’s essay, beauty and drama—as well as other traits like angularity, asymmetry, dancing, and originality—combine to make style, specifically and wonderfully, Black.

Like “Characteristics of Negro Expression,” Superfine describes characteristics of Black dandyism using twelve themes that are each transtemporal as well. The thematic groups—Ownership, Presence, Distinction, Disguise, Freedom, Champion, Respectability, Jook, Heritage, Beauty, Cool, and Cosmopolitanism—are arranged historically, beginning in the early eighteenth century and closing out in the present. Each group is introduced by a historical garment or object that exhibits a theme that is traced through to a contemporary garment or accessory by a Black designer working with explicit reference either to the motif or to apparel that exemplifies the topic.

Matthias Darly (British, ca. 1721–1780) and Mary Darly (British, 1736–1791). Portrait of Julius Soubise (“A Mungo Macaroni”), 1772. Engraving and watercolor on paper, 5 5/8 × 3 1/4 in. (14.3 × 8.3 cm). The Menil Collection, Houston (P69-283PC)

For example, “Presence” opens with a 1772 print of Julius Soubise, one of the first known Black dandies, and tracks his status from luxury slave to infamous man-about-town in eighteenth-century London. This grouping emphasizes florals, a nod to Soubise’s love of hothouse flowers and a way to explore the dandy’s “blossoming” as an individual. Juxtaposing historical and contemporary accessories such as a British perfume bottle (ca. 1750–55) in the shape of a bouquet and a carryall adorned with flowers from Virgil Abloh’s autumn/winter 2022–23 collection for Louis Vuitton, “Presence” both invokes and interrogates the romance associated with Soubise’s flourishing.

Gladys Bentley: America[’]s Greatest Sepia Piana Artist—Brown Bomber of Sophisticated Songs, 1946–49. Silver and photographic gelatin on photographic paper, with ink on cardboard, 5 1/4 x 3 3/8 in. (13.3 x 8.6 cm). Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture (2011.57.25.1)

Pivoting between a 1940s zoot suit and a white tuxedo designed by Brandon Murphy, “Jook” explores dandyism as a form of Black expressive culture with a particular relationship to music and nightlife. Here, zoot suits are spotlighted, as are tuxedos and their status as multifaceted “formal” garments. The tuxedo distinguishes its wearer, whether it is donned as a uniform by a service worker or as a dressy garment by a wealthy patron attending a fancy function or by an entertainer or musician appearing onstage. When worn by provocative women, like the blues singer Gladys Bentley, famous for her white tuxedo and top hat, the tuxedo can be an elegant vehicle for communicating a playful yet assertive queerness, a sharp-edged androgyny, and an unapologetic sex appeal.

There are multiple throughlines or narrative threads in the show, as it is a story about the archive of Black fashion and dress, about the numerous and diverse articulations of Black masculinity across time and space, about the imbrications of race, class, and sexuality, among many other possibilities. As much as it is an essay, the exhibition also functions as a group of related short stories about liberators, gentlemen, shape-shifters, artists, proud funky people on the move toward what artist Lyle Ashton Harris calls in “Black Widow: A Conversation” the “future perfect”—that is, “the need for an immediate political, aesthetic, and psychic intervention […] a new framework in which to refashion the body and mind.”

Mannequins made by Tanda Francis in her Brooklyn Studio produced for the exhibition.

Torkwase Dyson’s exhibition design and Tanda Francis’s bespoke mannequin heads both reinforce the openness and sense of possibility within the exhibition’s narrative. Dyson’s attention to Black dandyism’s relationship to liminality, agility, and resistance is everywhere, evident especially in the structures that she designed to hold—sometimes gingerly, at other times with a firmer grasp—the exhibition’s contents. Interested in the way in which dandyism can be an act of private self-creation or a performance of identity on a much larger stage, Dyson developed a version of her signature architectural shape language, or “hyper shapes,” for Superfine, focusing on the camera’s aperture and the proscenium stage, as well as on structures and design elements more evocative of mirrors and sight lines. Moments of concentration and flight communicate with others more reminiscent of display or resistance, strategic presence or absence, echoing the dandy’s play with a proud visibility or a necessary disguise. In their work for the exhibition, both Dyson and Francis were determined to invite ancestors into the space and honor them.

Gallery view of Superfine: Tailoring Black Style. The Lila Acheson Wallace Wing, The Iris and B. Gerald Cantor Exhibition Hall (Gallery 999). May 2025

Modeled on a likeness of one of the first Sapeurs active in early twentieth-century Congo, an African returning home from Paris, Francis’s mannequin heads feature this face rendered as if the figure were also wearing a mask. The gesture is meant to indicate both closeness to and distance from this African ancestry, and the mannequin head with the profiles seemingly comments on this tension. Designed to mimic the pages of an open book, the profiles enable each mannequin to be the site of different and multiple narratives. As a group, the profiled mannequins serve as ancestor figures as well as beacons of futurity in the exhibition space. Both the architecture and the mannequins guide the visitor literally and symbolically around the diaspora and across time.

In Olaudah Equiano’s memoir, achieving freedom and liberation is a function of imagination and will. As is the case with so many authors exploring, rhetorically and perhaps psychologically, the territory between enslavement and freedom, Equiano self-liberated long before his legal emancipation day and the purchase of his superfine suit. Like Frederick Douglass in his own narrative, Equiano was determined to show “how a man was made a slave [… and] how a slave was made a man”; self-fashioning, figurative and literal, is key to this process, a distinctive part of realizing and announcing humanity and self-worth. As a narrative of this journey, Equiano’s story is unique in that he is one of the only narrators who claims to remember his capture in West Africa, the Middle Passage, and the process by which an African becomes Black, British, diasporic.

In recent years, the facts of Equiano’s account have been questioned. In his book Equiano, the African: Biography of a Self-Made Man (2005), Vincent Carretta points to records that indicate Equiano may have actually been born in South Carolina, suggesting that, in an act of literary invention, he claimed African birth to bolster his narrative’s distinctiveness and suitability for the abolitionist cause. While some consider this aspect of the story disqualifying, I’ve always thought about this rhetorical flourish as the genius of the book; the whole text then privileges, on multiple levels, the power of imagination, the necessity of inventing possibility, the desire for diasporic connection as a means of survival and flourishing. Many, many years later, post-emancipation, in a moment of decolonization, another man confronting similar barriers to self-actualization, Frantz Fanon, declared, “In the world in which I travel, I am endlessly creating myself.” If Superfine: Tailoring Black Style communicates any one thing, I hope that it visualizes, through fashion, clothing, and dress, the liberating quality of the imagination, the profundity and joy, the self-making process enabled by cutting “no indifferent appearance.”

This essay is adapted from the catalogue Superfine: Tailoring Black Style, which accompanies an exhibition on view through October 26, 2025.