African Roots

Africa is the cradle within which humans became modern. It was in Africa that our ancestors were equipped with the imagination to create and shape the world we have inherited. From this source some embarked upon a global diaspora to blaze new trails. In the twenty-first century the place with the oldest past has the world’s fastest growing, most youthful population.

Africa’s diverse cultures represent a deep history of 160,000 years of experimentation with ideas, beliefs, and forms of expression. The pace at which these changes unfolded, though comparable to other regions of the world, has been less documented by societies that favored the oral transmission of knowledge. Across this vast continent, communities of nomadic hunter-gatherers have coexisted with those of mighty states. Archaeological investigation, analysis of some three thousand languages, and the study of material vestiges preserved in museums attest to a past as dynamic as the present.

The works in these galleries relate to the myriad cultural landscapes that blossomed south of the Sahara. Among those original sites of creation are storied hubs of global and regional trade, the affluent courts of powerful monarchs, and ephemeral, transient settlements. Artists and their workshops masterfully translated and amplified distinctive worldviews into creations that have endured beyond fleeting everyday experiences or rarefied events animated by dancers and musicians. From the seventeenth century some of those traditions were given new life in the Americas. Even fully isolated from those cultural contexts, these works of daring ingenuity have since the twentieth century been catalysts for innovators, inspired by their originality and arresting visual power, to take new leaps.

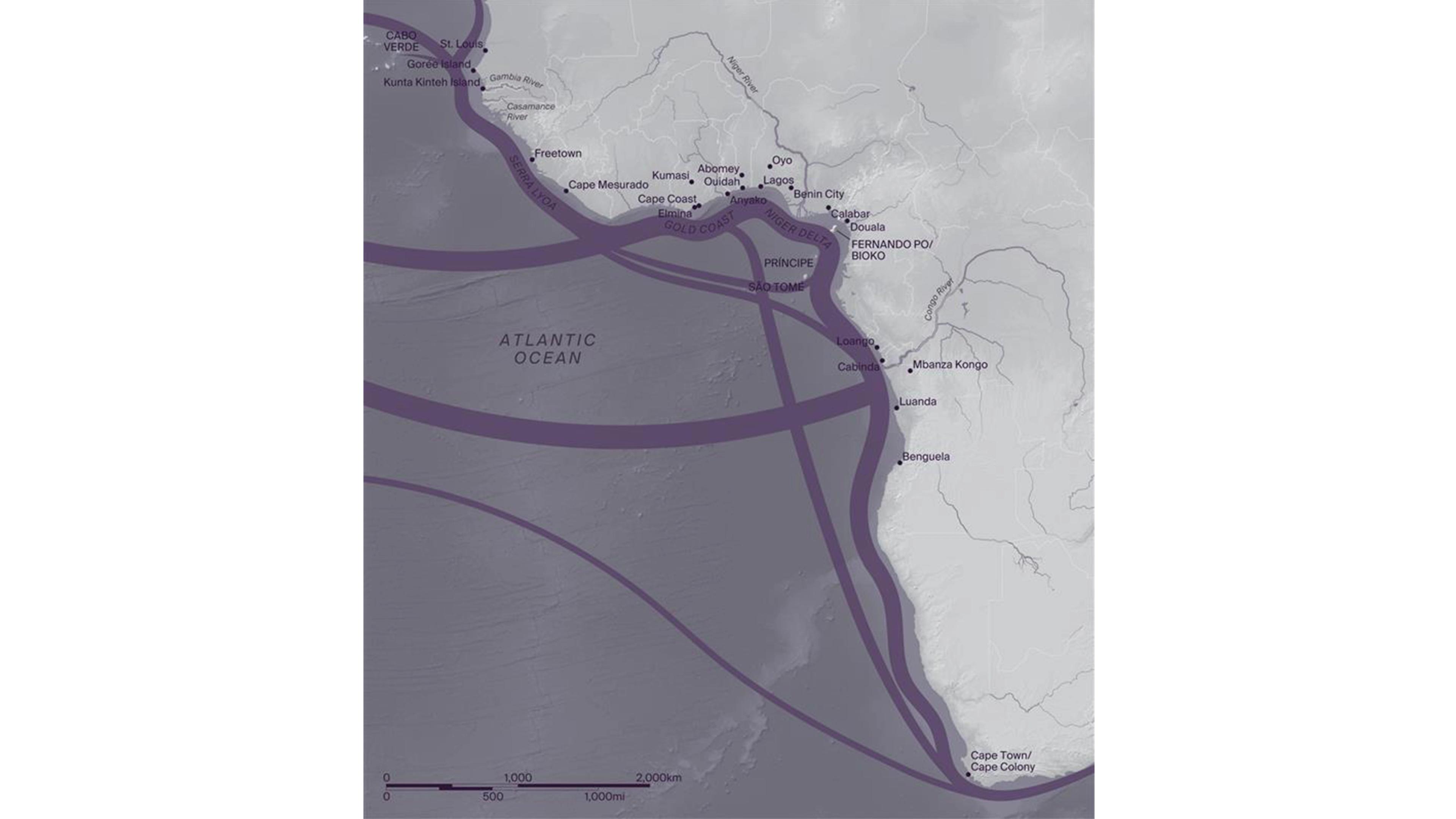

Africa’s Atlantic Coast Engagement

In 1445 CE a caravel vessel carried Portuguese navigator Dinis Dias to Africa’s westernmost point, Cape Verde, where his landing was rebuffed by its residents. That nautical breakthrough allowed Europeans to bypass the overland caravan routes that ferried West African gold across the Sahara. Despite regular points of contact between seaborne visitors and coastal populations, Europeans would remain largely confined to Africa’s periphery until the establishment of the Dutch Cape Colony at its southern tip in 1652.

From the 1470s, states across present-day Ghana’s shores brokered agreements with a succession of European maritime powers. The outsiders paid duties and rent for the right to build and operate a series of trading posts along what became known as the Gold Coast. Earliest among these fortified castles was Elmina (The Mine). Farther south, ships anchored seasonally in the natural harbors of Sierra Leone and the Niger Delta and Congo River estuaries. Regional leaders forged diplomatic ties with Portuguese emissaries and exchanged local gold, ivory, and pepper for copper, brass, and cloth. The firsthand observations and sponsorship of local artifacts for European princely collections by foreign merchants reflect admiration for the caliber of highly skilled artisans who worked in media ranging from weaving to metallurgy to ivory carving.

Exiles from Elmina to Robben Island

Dutch, French, Spanish, and English exploitation of “New World” territories in the Americas redefined transatlantic relationships. From 1640 European powers offered manufactured imports in exchange for prisoners of war generated by the expansionist campaigns waged by different African states. For the next two centuries, a forced exodus deprived the region of countless members of its productive youth. Not until 1792 were some of these captive individuals who had been sent to Britain, the West Indies, and North America “repatriated” by British and American abolitionists to Freetown in Sierra Leone and Monrovia in Liberia. In parallel, Dutch and English settlement of southern Africa led to the eventual development and implementation of an apartheid system of racial segregation that endured until the 1994 election of Nelson Mandela.

Africa’s Eastern Frontiers

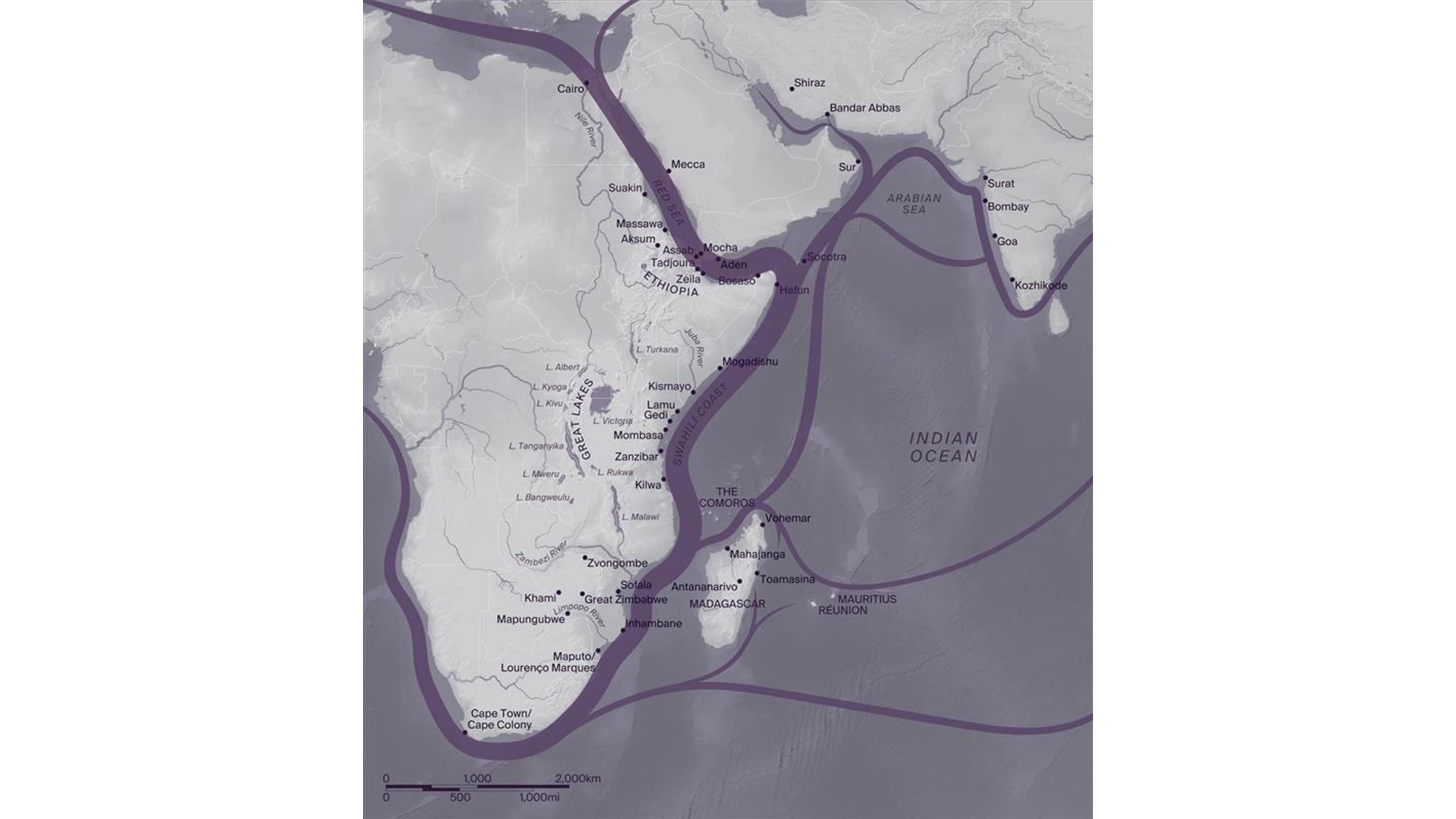

The Indian Ocean’s main currents are semiannually reversed by monsoon winds. Their east-west flow facilitated travel from coastal Africa to the Persian Gulf and Southeast Asia. Those dynamic networks of exchange connected the inland plateau of western Zimbabwe to China thanks to mainland and offshore entrepôts extending from the Red Sea to Mozambique. From the eighth century CE, these vibrant mercantile communities combined residents of the interior with Shi‘a refugees from southern Arabia. The lingua franca developed by the WaSwahili, or “people of the coast,” is a Bantu language that came to incorporate elements of Arabic, Farsi, Hindi, Portuguese, and English. Adherents of Islam, the prosperous merchant class that emerged sponsored both the continent’s earliest extant mosques and princely dwellings hewn from local coral.

Within the orbit of the Swahili city-states was the region’s largest island: Madagascar. Comprising eighteen officially recognized cultures, Madagascar was settled by migrants from the African mainland, including populations originally from Southeast Asia. That ancestry is reflected in both the local language—Malagasy, part of the Malayo-Polynesian language family—and the island’s distinctive commemorative rites. Among the Merina, ancestral remains are exhumed, danced, and wrapped in precious fabric shrouds before their return to collective tombs. The earliest state to arise there, around 1650, was that of the Sakalava in the southwest. During the 1780s, a new Merina dynasty shifted power from the coasts to the central highlands and prioritized self-sufficiency. Its leader, Andrianampoinimerina (r. 1787–1810), declared “rice and I are one,” promoting vast public works to spur cultivation of the sacred staple.

Busa‘idi Colonization of the Swahili Coast

Many centers along the Swahili coast came under Omani colonial control in the nineteenth century with the expansion of the Busa‘idi Sultanate, initially based in Muscat. Sultan Sayyid Sa‘id (1790–1856) introduced clove plantations, which required enslaved labor from the African mainland, and relocated his capital to Zanzibar by 1810. The wealth gained from that economic shift, as well as the accompanying influx of artisans from the Arabian Peninsula and South Asia, led to a dramatic expansion of techniques and styles for working coral stone and wood. Despite the official abolishment of the transatlantic slave trade in 1807, slavery remained legal in the Zanzibar Protectorate until 1897 and continued in various forms through the early twentieth century.

Ancient Africa

History begins in Africa. It was there that our earliest creative endeavors and civilizations were ignited. Evidence of that relatively unfamiliar legacy is absent in most museums. In this threshold between the sub-Saharan Africa galleries and those devoted to Greek and Roman art, we highlight traces of ancient traditions that lie beyond the scope of The Met collection.

Footage on the nearby screen features rock paintings from the Kalahari Desert that relate to creative practices developed some 75,000 years ago by Khoisan-speakers living across eastern and southern Africa. These highly mobile hunter-gatherers painted with natural pigments, using their fingers or bird quills to delicately add their signature to the landscape. Their imagery teems with carefully observed fauna, graceful male hunters, and shamans. Conceived as potent thresholds into a spiritual realm, the site-specific creations have drawn the engagement of successive generations, with new layers and additions contributed as recently as the early twentieth century.

Settlement of the Upper Nile led to the emergence of the region’s earliest states and towns. Those situated in the Sudanese reaches of the Nile became a conduit for Africa’s rich natural resources, including gold, granite, precious woods, and elephants—in great demand across the ancient world. From 2400 BCE to around 350 CE, the states of Kerma, Napata, and Meroe were closely linked to ancient Egypt in an evolving relationship of trading partner, rival, colonizer, and vassal. The Meroitic works on display here, excavated in present-day Sudan a century ago, constitute a bridge with the Museum’s Egyptian galleries.

The Nok Culture

Absent from most museum collections is evidence of Nok, a civilization contemporaneous with ancient Egypt and Kush. Traces of this society were rediscovered in 1928 when tin miners in Kaduna State, Nigeria, unearthed works made of fired clay. The first excavated artifacts were transferred directly to Nigeria’s newly established National Museum in 1943. While this culture was initially thought to have begun around 500 BCE, more recent research has moved its origins back to around 1500 BCE. Already equipped with advanced iron-smelting technology by 900 BCE, Nok artists began producing complex terracotta sculptures representing humans, animals, and hybrid creatures. Their human subjects feature prominently outlined triangular-shaped eyes with perforated pupils, elaborate hairstyles, and are often draped in extensive beadwork. While the latest research by the Frankfurt Nok Project suggests that this practice waned around 400 BCE, it was likely a foundation for later creative output at sites such as Ile-Ife in southwestern Nigeria. To date, Nok is the earliest known tradition of large figurative sculptures in Africa, outside of ancient Egypt.

A Nok terracotta, photographed as part of a campaign to digitize the Nigerian National Museum collections, in partnership with The Met, 2024. Courtesy of Juan Trujillo and Chris Heins

Deep History of the Sahel

Cultural artifacts are among the rare concrete traces of the many-layered history of continuous change that has unfolded in the western Sahel. Thousands of years ago, local farmers began exchanging their surpluses with those of regional herders, fishermen, hunters, salt miners, and iron smelters. These trade patterns led to the emergence of cities south of the Sahara. As early as the third century BCE, the settlement of Jenne-Jeno, situated within the Niger River floodplain, yielded abundant biannual crops. Its strategic location allowed for the transfer of goods by river and overland routes. Around 800 ce an outer wall demarcated the densely packed mud-brick homes of an ethnically diverse, egalitarian urban center organized by professional districts. Its residents included builders, metalsmiths, and potters responsible for complex figurative representations.

During the fourteenth century this region was part of the Mali Empire. Around 1400 Jenne-Jeno was suddenly abandoned for a new settlement a little over a mile north. Modern Jenne became a renowned Islamic center whose Great Mosque is the world’s largest adobe structure. It remained an important city over time, controlled by the Songhai Empire in the mid-fifteenth century and Morocco’s Saadi dynasty in the late sixteenth. In the nineteenth century it became a strategic site in conquests by rival Islamic dynasties, first the Masina, then the Tukulor.

The Bandiagara Escarpment: A Natural Sanctuary

Situated over sixty miles north of Jenne, caves within the Bandiagara Escarpment were used as secure chambers for storing reserves of grain and for ancestral burials as early as the eleventh century. In the wake of the dissolution of a succession of West African states, the elevated and impregnable cliffs offered refuge to those dispersed populations. Upon their arrival during the fifteenth century, the Dogon—who traveled from Mande (likely situated in present-day Guinea)—referred to the people who preceded them as tellem, or “we found them.”

Manifestations of Faith

The western Sahel’s earliest communities transformed its landscape. They built funerary mounds, arranged hewn-stone megaliths, and buried clay figurines as extensions of diverse faiths. From the eighth century, camel caravans carried gold, ivory, and enslaved people from the interior of the continent across the Sahara. That perilous passage over an ocean of sand, traversed by migrants to this day, expanded regional trade networks by connecting West Africa to southern Europe. Among the cultural exchanges sparked by this commercial superhighway was the adoption of Islam by many of those living along the northern bend of the Niger River and in the Middle Senegal River Valley.

In a region where people had prioritized the spoken word and oral history for the transfer of knowledge, Islamic practices introduced a textual tradition. Muslim converts adapted and expanded existing local forms of expression so that their new faith might flourish alongside earlier belief systems. Both sanctuaries for ancestral worship and centers of Islamic learning were informed by the fluid design of renewable mud-brick architecture used for domestic living. That legacy remains alive in the array of figurative traditions and striking sculptural adobe mosques developed by Soninke, Jenne, Tellem, and Dogon artists. These wondrous, artistic acts of devotion accompanied prayers for divine intercession by individuals whose life experiences are often otherwise unrecorded.

Emperor Mansa Musa’s Patronage and Timbuktu’s Great Mosque

Immediately following his 1324 pilgrimage to Mecca, or hajj, ancient Mali’s leader Mansa Musa was portrayed by Majorcan cartographers on maps of the known world. Accompanying his image is one of the major landmarks he sponsored upon his return to the city of Timbuktu: the Great Mosque. It was in this center of learning that, in 1656, Islamic scholar ʿAbd al-Rahman al-Saʿdi wrote the first chronicle of the region’s history, or tarikh, in Arabic.

The Art of Cultivation from the Rice Coast to the New World

Guinea’s rainforests have been home to a diverse population going back as many as eight thousand years. Linguistic analysis suggests that among the earliest groups concentrated in southern Senegambia and Guinea were ancestors of the Dyula and Temne. Between the first and second millennia BCE, forebearers of Mande societies descended from the inner delta of the Niger River to occupy inland rainforests along the Guinea coast. They carried with them the precious staple of African rice and the knowledge of how to domesticate it, developed some 3,500 years ago. In adapting rice cultivation to a new landscape, Mande ancestors converted mangrove swamps into paddy fields. To this day, rice planting, harvesting, milling, and cooking across Guinea and Sierra Leone are overseen by women. In Baga communities, dances of imposing d’mba headdresses celebrating the ideal of mature womanhood once presided over the commencement of planting. Women were similarly honored among the Mende with elegantly carved ladles used to serve rice, attesting to their bountiful generosity as hosts.

African rice purchased by ship captains to feed their captives during the Middle Passage of the transatlantic slave trade seeded gardens planted by Africans in the Carolinas of North America. Demand for enslaved labor resulted in a new order of warfare and insecurity for many of the small polities along the Guinea coast and its inland region. The development of civic associations such as Poro and Sande played an important role in furthering social cohesion in the midst of immense change.

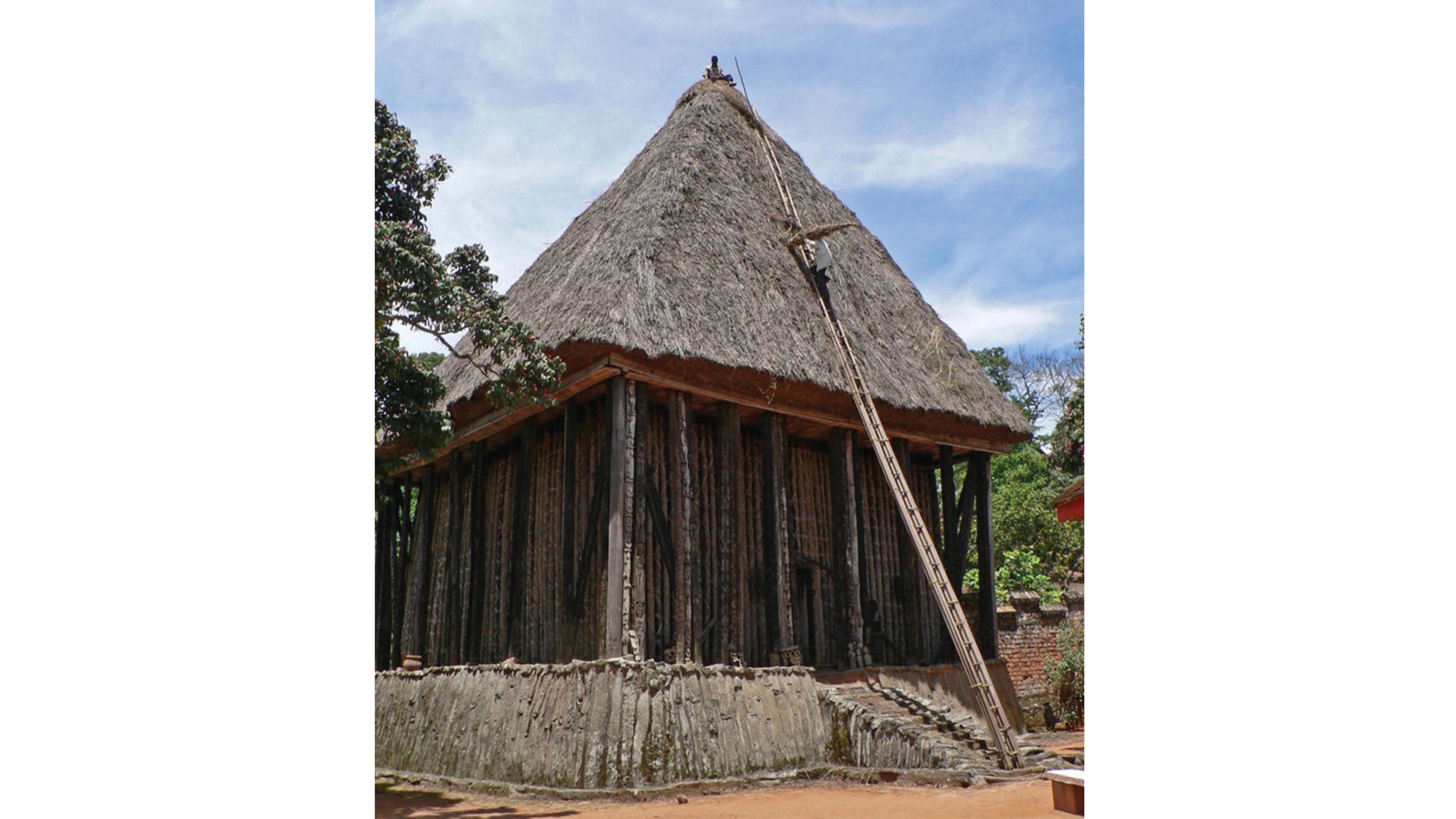

The States of Highland Guinea and the Grand Mosque at Timbo

From 1725 the Fulani Imamate of Futa Jallon exercised a major influence over the territory extending from Sierra Leone to Senegambia. From its capital of Timbo in Guinea’s mountainous highlands, the state waged campaigns to the south for captives under the ideological guise of converting the population to Islam. In 1878 the region also saw the formation of a neighboring Islamic Mandinka, or Wassoulou, Empire by Samory Touré (ca. 1830–1900). The son of Dyula cattle traders, Touré strategically laid claim to gold mines and key centers of trade. That wealth allowed him to amass a formidable army to counter French imperial ambitions and convert subjects across West Africa until his capture and exile in 1898.

Begun circa 1727, Timbo’s original mosque—pictured here—consisted of multiple round buildings whose stepped thatched roofs and adobe walls were similar to those of Fulani domestic structures. In 2016 the structure was replaced by a mosque modeled after a Middle Eastern prototype.

From the Asante Empire to Modern-Day Ghana: The Radiance of Akan Courts

For Akan speakers, gold is the earthly counterpart to the sun and the materialization of kra (life force). During the first millennium CE, their ancestors developed techniques for extracting this luminous substance from plentiful deposits in rainforests near the Black Volta River. Burgeoning chiefdoms deployed gold in regalia and exported it, along with kola nuts, north through Saharan networks. In response to global demand, they acquired enslaved labor to expand its exploitation. In 1482 Portugal established Elmina Castle as an Atlantic trading post along what became known as the Gold Coast.

The earliest Akan polities to compete for control of interior goldfields and routes to such coastal outlets were the Denkyira and the Akwamu. Around 1680, Osei Tutu (ca. 1660–ca. 1712), military leader of the Oyoko clan, joined forces with the powerful priest OkomfeAnokye to create a federation of Akan states known as Asante. Under Tutu’s successor, Opoku Ware (1700–1750), Asante came to encompass most of present-day Ghana. During that period of interior military conquest, its war captives were sold to transatlantic traders. Britain claimed the Gold Coast as a colony in 1821 and, following a war with Asante, destroyed the capital of Kumasi in 1873. In 1957 a new era of independence from colonialism was ushered in when Kwame Nkrumah (1909–1972), a teacher from the southern Gold Coast, became Ghana’s first president.

Dwellings of the Gods and Ancestral Stool Rooms

Abosom (divinities) are among the protective spiritual forces that Akan clans have relied on to maintain social order. Endowed with human qualities, they are often provided with regalia and housed in special rooms or compounds. Within spaces relating to the Asante state, the stool has served as a national symbol or as a ruler’s personal seat. The stools of a deceased chief or queen mother, blackened with soot, become the sites of periodic offerings within a dedicated chamber. The Asante recount that at the time of their consolidation, the divine Golden Stool, or SikwaDwa Kofi, descended from the heavens on a Friday as a vessel for the nation’s sunsum (spirit).

Danhomé, or “In the Stomach of the Serpent”

To consolidate and legitimize their rapid ascent to power during the eighteenth century, the monarchs of Dahomey (or Danhomé) claimed descent from the union of a Tado princess and a leopard. Dahomey royalty and their subjects were linked to a pantheon of thousands of vodun, or gods, often associated with forces of nature. Among these was a serpentine rainbow deity who promoted health and well-being. Communication with the spiritual realm was maintained through prayer and sacrifice. When Dahomey became a tributary state of the Yoruba Empire of Oyo, from 1748 to 1818, its leaders embraced Fa, a system adapted from the Oyo tradition of Ifa divination. The Fa sign of each sovereign defined his reign and inspired sponsorship of empowering sculptures.

Following King Agaja’s (r. 1718–40) capture of the Atlantic port of Ouidah, Dahomey gained direct contact with European slave traders. With that access, its leaders prioritized the expansion of an economy largely based upon the sale of men captured in annual military raids. From 1710 to 1810, over a million individuals of Aja, Ayizo, Fon, Gedevi, Mahi, and Nago descent from neighboring communities departed present-day Benin as unwilling participants in one of the most massive intercontinental population displacements in history.

With the abolition of the slave trade, Dahomey shifted its economy to supply newly industrialized nations with palm oil obtained through prison labor. In 1889 failed military and diplomatic negotiations led to King Gbehanzin’s (r. 1858–89) exile to Martinique and the occupation of the capital, Abomey, by French forces.

Artistic Expression in the Abomey Palace

Remembered as an innovator and patron of architecture, King Agaja commissioned Dahomey’s first palace in Abomey. Palace buildings were made of red earth mixed with palm oil and fiber. To harness the rising sun, associated with life and well-being, east-facing entrances were added to its southern end. With each subsequent ruler, new entryways and buildings were continually constructed to the south, expanding the complex. Since 1945 the palace has housed the Historical Museum of Abomey; it was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1985. The complex’s bas-reliefs glorify kingship by illustrating major events from a ruler’s ascension to his victories in battle. They were the focus of a 1994 restoration campaign by the Getty Conservation Institute.

Among the other distinctive visual forms of expression produced at court were vibrantly hued appliqué textiles created by the Yemadje family of royal tailors. These included tokpon, eighteen-foot-high tents incorporating references to royal history and power, set up outside the palace to mark an annual cycle of ceremonies known as huetanu.

Liberia: Dual Heritage in “The Land of Freedom”

By the eighteenth century, the Atlantic shoreline extending around present-day Monrovia was home to the Dei, Grebo, Kru, and Vai peoples. Farther inland, the forested plateau was occupied by Gola, Dan (Gio), and Mano communities. The powerful Kondo confederation, composed of many of these groups, controlled trade routes between the coast and interior. In 1822 its Malinke ruler, Sao Boso, embraced an influx of freeborn and formerly enslaved Black settlers from the United States. Over the next decades, some twenty-five thousand individuals arrived from Virginia, North Carolina, and Georgia under the direction of the American Colonization Society (ACS). Some Dei and Gola leaders fiercely opposed the transplants and resisted their settlement. Ill-equipped for the climate and lacking local immunity, nearly half of the North Americans died of malaria soon after their arrival.

Initially confined to the coast, the vulnerable minority instated social barriers that set them apart and reinforced their outsize economic dominance. In 1847 Virginia-born Joseph Jenkins Roberts established a republic with a constitution modeled on that of the U.S. and served as its founding president. That nation, Liberia, expanded its territorial claims, exacting taxation and suppressing indigenous systems of worship, education, and chieftaincy. The social and economic transformations wrought by these policies profoundly impacted many of the cultural traditions highlighted in this gallery. Faced with their increased marginalization and new financial obligations, some local elders elected to sell familial masks to foreigners, including missionaries and researchers. Long-standing tension over the privileged status of Americo-Liberians was the catalyst for a civil war that consumed the final decades of the twentieth century.

From Washington, D.C. to Dazoe

Founded in 1817 with support of prominent Quakers, the American Colonization Society (ACS) comprised an unlikely coalition of White clergymen, abolitionists, and slave holders who advocated for “repatriation” of emancipated Black populations. Four years later, under President James Monroe, agents for the ACS negotiated with King Peter, the Dei spokesman, for the title to Cape Mesurado as a resettlement colony. In the subsequent years Dei signatories denied the treaty’s validity. A massive cotton tree on Dazoe, later known as Providence Island, was the site of the 1822 encounter between the existing population and those newly arrived in “The Land of Freedom.” Since the tree’s collapse in 2019, its base has been the site of salvage excavations by the Back-to-Africa Heritage and Archaeology Project. Their work has unearthed thousands of artifacts contemporaneous with that inaugural meeting, as well as objects that date further back to the region’s earliest settlement.

Bamanaya : Worldview and Ritual Actions of the Bamana

Across the Sahel, the concept of nyama is at the core of Mande-speaking peoples’ beliefs. An energy innate to all organisms, this spiritual force or spark of vitality activates the affairs of the universe. While such tenets of devotion coexisted with Islam for centuries, communities that prioritized their retention came to be identified as “Bamana” (literally, “nonbelievers”). Among the foremost Bamana centers of power at the beginning of the eighteenth century was the city-state of Segu.

Known for his political acumen, Segu’s founder, Biton Kulibali (r. 1712–55), presided over a court sustained by agricultural labor and seasonal campaigns led by its courageous hunter-warriors. Under his leadership, the tonjonw (a youth volunteer association) gradually became a professional military. Captives taken in battle were incorporated into local regiments or sold within Saharan and Atlantic commercial networks for arms, munitions, horses, and luxury goods.

Four great boliw (portable altars), cornerstones of Segu’s state religion, were critical to the leader’s acquisition and maintenance of power. Priests served as boli (singular) caretakers, officiating over rites in which sacrifices were made to summon the nyama necessary for success in farming, hunting, and war. Across Bamana communities, broad participation in more than half a dozen regional religious, political, and philosophical initiation associations also contributed importantly to fostering a sense of social cohesion and harmony.

Segu: A Citadel on the Banks of the Niger

Although Segu’s residents prior to the nineteenth century were mostly animists, Soninke Muslims—a Mande-speaking group whose ancestors were founders of the ancient Ghana Empire—sponsored Qur’an schools, mosques, and judges. Nonetheless, Islamic reformists such as Al-Hajj ʿUmar Tal, a Tukulor scholar, holy man, and commander, identified Segu as a “citadel of paganism” and the prime target of his military jihad. Following the city’s 1861 conquest, the state boliw were publicly destroyed and its populace required to convert. Segu remained the capital of the Islamic Tukulor Empire until its capture by the French in 1890. Since Mali’s independence in 1960, it has become the country’s second largest city.

An Interwoven Dyula and Senufo Past

A quest to expand regional markets spurred Mande entrepreneurs from the Upper Niger to venture southward during the fourteenth century. Distinguished from local farmers as dyula, or “traders,” these Muslim merchants established a weaving industry and a number of vibrant centers of commerce. Notable among these was the city of Kong that became the capital of a culturally heterogeneous state established by the dynasty of Dyula leader Sekou Ouattara no later than the early eighteenth century.

Encompassing communities of animist Senufo cultivators, Kong prospered through its control of important trade routes that extended northward to Kankan in eastern Guinea. At its height in the 1730s, Kong reached from the Asante Empire in the east, to Jenne in the north, and westward to the Bamana states. Around 1750 Kong’s armies waged military campaigns over those western territories. The independent cultural and artistic centers of Korhogo, Nielle, and Kadioha were established as chiefdoms in what is today northern Côte d’Ivoire. Following Kong’s 1895 razing by Samory Touré, the Dyula cleric and famaa (military leader) of the Wassoulou, or Mandinka, Empire, the city became a center of Islamic learning. In his campaign to create a new Muslim state, Touré made demands for tribute from Senufo populations that led them to rebel. After he retreated in 1898 in the face of a French invasion, the region’s major chiefdoms were turned into administrative districts.

Sinzanga: Poro’s Sacred Groves

At the level of local communities, participation in the civic institution of Poro has historically offered Senufo men an alternative leadership structure to being governed by a paramount chief. Poro’s meetinghouses and schools are situated within the forested landscape adjacent to the village; the entrance to these sacred groves, or sinzanga, is forbidden to noninitiates. A Poro chapter’s sinzanga was the family compound and residence of the Ancient Mother. The rites celebrated there, ranging from the graduation of a generational cohort of her “children” to the funeral of a venerable senior “son,” were heightened by dramatic statuary. These works paid tribute to her presence through the forms of majestic hornbills, ideally balanced male and female evocations of the first human couple, and masquerades portraying fantastical otherworldly beasts.

Initiates perform in the sinzanga as part of their entry into tchologo, the final stage of initiation into adulthood, Nambakaha village, Mali, 2001. Photograph by Syna Ouattara

Birth of the Baule: “The Child is Dead”

Successive waves of Akan departed their homelands during the eighteenth century, moving three hundred miles westward from Kumasi, capital of the Asante state. One catalyst for their exodus was a dispute over succession between Opoku Ware and Dakon, nephews of Asante’s founder, Osei Tutu. When Opoku Ware prevailed, his rival’s followers fled the Kumasi army. According to legend, their escape was secured by Dakon’s sister, Awura Poku, through the sacrifice of her newborn son on the banks of the Comoé River.

Once settled in the forest region of present-day central Côte d’Ivoire, their descendants maintained ties with the Akan heartland through overland trade. They exchanged gold, ivory, woven cloth, and enslaved individuals for guns and ammunition. Equipped with armaments imported by Dutch and English traders along the Gold Coast, the more recent Akan arrivals asserted themselves over prior residents with whom they also forged marriage alliances. These included members of Dida, Guro, and Wan groups whose ancestors had previously migrated from southern Mali between the thirteenth and sixteenth centuries. The formation of a new Baule society was defined by the blending of these traditions with Akan culture. During the nineteenth century the Baule participated in the palm oil trade along the coast and fiercely resisted French colonial rule. In 1960 the son of a Baule chief, Félix Houphouet-Boigny, became the father of the new nation of Côte d’Ivoire.

The Force and Splendor of Baule Ancestors

The Baule ancestral world (blolo) is known as the “village of truth.” It is the source of insights into the fate of the living as revealed by diviners. Each household’s adja, or treasure, is material evidence of familial unity and ancestral force. It encompasses a rich accumulation of gold ornaments, nuggets, and foil-wrapped sculptures, as well as cash, woven cloth, and ancestral stools. The standing of the chiefly custodian of this repository was measured by the extent of the wealth displayed around him before his burial and transferred, at his funeral, to a successor.

An ancestral shrine and sacred family treasure, Old Kami, Côte d’Ivoire, 1972. Photograph by Susan Vogel

Mossi Might and Ouedrago, “The White Stallion”

Ouagadougou and Yatenga were among the most powerful of a series of rival Mossi principalities that arose at the headwaters of the Volta River (situated in what is now central Burkina Faso) during the fifteenth century. They traced their common origins back to the state of Dagomba (in present-day Ghana), whose legendary warrior princess, Yennenga, led her father’s armies to victory. Denied permission to marry, she fled north. There, her firstborn son, Ouedrago, founded the Mossi state. Its cavalry advanced in all directions, subjugating farming communities to the south and challenging the mighty Mali and Songhai Empires.

Descendants of Ouedrago’s nakomsé (conquerors) served as political rulers who raised armies, collected taxes, and preserved order in Mossi society. Ouagadougou’s citizens maintained the superiority of their leader, whose vast realm, wealth, and might was likened to that of the sun. Invested with power to intervene with their royal forebearers, Mossi chiefs were annually petitioned by clan elders to secure ancestral blessings for the benefit of the community. The diverse groups brought under Mossi authority included the Dogon, Kurumba, Nuna, and Winiama, who adopted a common language and identified as nyonyosé (ancient ones) or tengabisi (children of the earth). Despite their assimilation, traditions of masquerades and priests devoted to maintaining the spiritual protection afforded by founding ancestors endured.

Adobe Canvases: Tiébélé’s Architectural Facades

To fortify themselves against raids by Mossi cavalry, Gurunsi communities (located in present-day south-central Burkina Faso and northern Ghana) developed a tradition of defensive structures with thick earthen walls. Men constructed these barriers during the dry season, after which they were strengthened by women, who applied layers of geometric and representational motifs to their exteriors. Established by the sixteenth century, the village of Tiébélé is celebrated for the caliber of its vivid decorative programs of freehand painting, engraving, and reliefs rendered with red laterite, white kaolin, and black graphite pigments that relate to clan historical narratives and legends. The repertoire of ancient imagery passed down generationally is renewed through annual repainting. In 2024 Tiébélé was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List.

Early Technological and Urban Development in Nigeria

Furnaces unearthed near Taruga on the slopes of north-central Nigeria’s Jos Plateau attest to the extraction of iron ore through smelting as early as 400 BCE. The crucible for the dissemination of this advanced metallurgy was a series of small farming communities identified as Nok. That society also stands out as the source of a veritable explosion of creativity in the form of complex, fired-clay figures draped in beaded finery and crowned with elaborate hairstyles. These works constitute sub-Saharan Africa’s oldest surviving sculptural tradition.

The earliest instances of regional mastery of the casting of copper-tin alloys is evident in the contents of ceremonial deposits, including a burial at the ninth-century CE site of Igbo-Ukwu. Created through the lost-wax process, the artifacts began as wax prototypes that were covered in clay. Casters then poured molten, metal into the casings, melting the wax to produce original works.

As early as the sixth century CE, ancestors of Yoruba-speaking people formed densely populated centers that are the foundations of Nigeria’s modern cities. Among the most influential of the early city-states that arose was Ile-Ife. The ancient urban character of this nexus is reflected in the city’s walls (which contain traces from the eleventh century), network of shrines, monumental stone sculptures, planned building complexes, domestic and communal altars, and elaborately patterned potsherd-and-stone pavements.

Ile-Ife: The Birthplace of Humankind

Members of the Yoruba pantheon regularly enter the physical world through their worshippers, mediums who are trained to receive their spirits. The gods’ faces and abodes are the shrines, temples, sacred forest groves, and festivals where they are propitiated and served. Placed within to beautify these sites of worship are images of the devotees themselves whose acts of veneration empower that god.

During his 1910 visit to Ile-Ife, German researcher Leo Frobenius learned that its some four hundred sacred groves were the burial sites of exceptional antiquities. The presence of those extraordinary creations has been viewed as evidence in support of the foundational place Ile-Ife holds in Yoruba accounts of genesis.

Kingdom of Benin

Benin court historians trace the lineage of Ọ́bà Ẹ́wúarè II (r. 2016–present) to a dynasty established around 1200 ce with the arrival of Ọ́rànmíyàn, a Yoruba prince from neighboring Ife. Under Ọ́bà Ẹ́wúarè I (r. ca. 1440–73), the formation of a powerful standing army extended Benin’s territories from the Niger Delta in the east to the coastal lagoon of Lagos in the west. This dynamic, rising state gained further regional dominance through trade with a succession of European partners. As early as 1486 Benin exchanged pepper, cloth, and ivory with Portugal for metal and an influx of other luxury goods. Portuguese mercenaries supported Benin’s military campaigns against regional enemies; prisoners of those conflicts were sold as part of the transatlantic slave trade. The resulting wealth was directed by Benin’s leaders toward the patronage of a dazzling array of artifacts conceived as reflections of a glorious dynasty.

The momentum to expand Benin’s physical and creative frontiers, led by a succession of warrior ọ́bàs (kings), shifted at the end of the seventeenth century. Rebellious chiefs challenged the ọ́bàs’ authority, and great dynastic turmoil and civil war prevailed. During Ọ́bà Ádọ̀lọ́’s rule (r. ca. 1848–89) Benin’s political and economic hold on its tributaries was seriously weakened by conflicts along its northern and eastern borders and by British incursions from the coast. Bitter internal feuds divided the court of his son Ọ́bà Òvọ́nránmwẹ̀ (r. 1889–97). Although Òvọ́nránmwẹ̀ signed a favorable trade agreement with Britain in 1892, seditious rival chiefs ambushed and killed a British delegation on its way to Benin City, making the kingdom a target of a devastating retaliatory military strike. This attack resulted in the the loss of life of hundreds of Benin’s citizens, the wounding and displacement of thousands of survivors, and the seizure of the palace’s contents.

Reconstruction and Beyond

In 1897 the British set fire to the residences of the queen mother and important chiefs. As the blaze spread, much of Benin City was destroyed, including the Royal Palace. Upon his accession in 1914, Ọ́bà Ẹwẹ́ká II undertook the building’s reconstruction, commissioning replacements for the palace altars dedicated to his predecessors. That process of renewal continues to this day under Benin’s thirty-ninth ọ́bà, Ẹ́wúarè II. Situated within modern Nigeria’s southern province of Edo, the city now has a population of two million. The urban fabric of this storied former imperial capital continues to expand, incorporating new landmarks. In parallel to growing international awareness of the caliber of Benin’s historic art, Ẹwẹ́ká II prioritized the revival and modernization of guilds. Since 1999 both the palace and Igun Street—headquarters to Ìgùn Ẹ́rọ̀nwwọ̀n (the brass-casting guild)—have been designated as UNESCO World Heritage sites. In the accompanying footage, the lost-wax casting method deployed by the guild since the late fourteenth century is demonstrated by its head, Chief Kingsley Osahanhen Inneh.

Grassfields Principalities

A concentration of prosperous city-states arose several centuries ago across the Grassfields, the verdant mountainous plateaus of Cameroon’s densely populated West and Northwest regions. A fon (ruler, also written as fwa or foyn) presides at the apex of each of the some 150 distinct, hierarchically structured monarchic polities. Paramount civic, spiritual, and military authorities, these leaders remain the embodiment of their peoples’ cultural traditions and values. Exacting protocols honor the passing of a fon and secure his favorable engagement as a royal ancestor. A ritual transfer of power transmits the life force and attributes of the deceased sovereign to a successor spiritually fortified to assume the role.

Within this competitive cultural landscape, the caliber of the art commissioned by a Grassfields court contributed fundamentally to its standing. Customized palace compounds, conceived of as avatars of the fon, became important demonstrations of preeminence. During the first half of the twentieth century, monumental building campaigns across the Grassfields spurred a vast and imposing architectural legacy. Constructed of perishable plant materials, such landmarks required constant renewal. Annual palace refurbishment was marked by the nja festival, featuring the full panoply of state-sponsored visual insignia, from thrones and masquerades to opulent dress.

The Bafut Palace (Nto-o Bafu)

The palace at Bafut, one of the Grassfields’ most influential principalities for the last century, has been a residence of the fon and the all-powerful Kwifor, a council of elders whose members served as a check on royal power. It was rebuilt in 1907 after a disastrous fire. A designated UNESCO World Heritage Site, the complex includes a public audience hall, quarters for the fon and his closest personal attendants, assembly houses for palace societies, storerooms, and structures for shrines and altars. When Fon Abumbi II ascended the throne in 1968, the palace treasures he inherited were transferred from storerooms to a private museum on the palace grounds so that they might be better preserved and made accessible to outside visitors. Works from that living collection are actively deployed in the ongoing ceremonial life of his court.

Restoration of the Achum Shrine, Bafut Palace, 2011. Courtesy of the World Monuments Fund

Carrying Ancestors Through Equatorial Forests

Equatorial Africa’s luxurious rainforest is defined by unparalleled ecological diversity. As early as 40,000 BCE the Batwa (or “firstcomers”) began harnessing the properties of its eight thousand plant species. A massive population movement later unfolded over thousands of years, expanding the region’s residents to include some fifty culturally distinct Bantu-speaking groups. In addition to venerating the founders of their own lineages, more recent arrivals recognized the indigenous Batwa as spiritual mediators in their newly adopted lands. Those widespread core beliefs inform Bwiti rites, developed by Tsogho-speaking communities concentrated in Gabon’s Chaillu Mountains and adapted across the region.

Fang clans, newly arrived from northeastern Cameroon in the eighteenth century, supplied European traders’ demand for ivory and ebony. In order to foster benevolent ancestral engagement in village affairs, familial leaders carried with them sacred relics of their illustrious forebearers. Imbued with power, these were retained within byeri altars—bark receptacles whose lids featured guardian figures. A focus of Fang youth education was the mastery of clan genealogy, accompanied by performances in which elders animated an altar’s figurative elements.

In response to Catholic and Protestant missionizing, the Fang relinquished the use of byeri and adopted Bwiti rites blended with elements of Christian devotion. Once abandoned, many byeri sculptural elements were sold to foreign visitors. Their appearance abroad proved a source of fascination for the twentieth-century avant-garde, who carefully studied their formal qualities.

The Ebandza, or Bwiti Temple

Until the nineteenth century, Fang communities relocated every decade. Their villages were ephemeral settlements until the construction of roadways and administrative centers ushered in the adoption of more fixed sites. Bwiti initiates frequently observed that the need for communion, once fulfilled by rites relating to portable reliquaries, was supplanted by worship within an ebandza structure. The right side of this rectangular chapel is associated with life, the sun, and men; the left with death, the moon, and women. The structure’s central pillar that supports the roof beam is situated at the front entrance. Conceived of as a cosmic axis that roots activities in both heaven and earth, it is often carefully sculpted. The ngombi harp is played at the base of a protective rear pillar. Bwiti writings equate the ebandza’s layout to that of a supine male body whose genitals, head, and heart correspond respectively with the central pillar, back, and hearth.

Kongo: A Mighty Civilization

The Congo River, known in the Kongo language as nzadi (large river), flows nearly three thousand miles from northeastern Zambia to the Atlantic Ocean. The surrounding area was settled by Kongo peoples as early as the seventh century CE. The arrival of Portuguese navigator Diogo Cão at its estuary in 1483 inaugurated contact between two world leaders: the Kongo sovereign Nzinga a Nkwu (r. ca. 1420–1509) and King João II of Portugal (r. 1481–85). Within a decade, Nkwuelected to be baptized as João I. His court embraced literacy and adapted Christianity to their own cosmology.

Initially, Portuguese ships streamlined the original overland trade networks, managed by leaders of regional polities, by ferrying commodities between coastal centers. A major shift occurred in the late fifteenth century when Kongo’s leaders supplied European entrepreneurs with prisoners of war as labor for sugar plantations on the island of São Tomé. Seeking to directly capitalize on the region’s mineral and human resources, Portugal invaded the neighboring Kingdom of Ndongo in 1575, establishing the colony of Angola. Regional leaders jockeyed to maintain autonomy and control of commercial routes in the ensuing climate of endemic conflict.

During the second half of the nineteenth century, foreign traders ventured inland, bypassing local chiefs in pursuit of local resources. Kongo artists continued to direct creative energies toward the well-being of their communities, producing critical bridges with the spiritual realm. This is evident in the forms of pensive commemorative tributes to Kongo lords as influential intermediaries and awe-inspiring power figures charged with deflecting aggression.

Wealth in People

In Kongo society, the ultimate measure of wealth was the number of one’s dependents, or mbongo bantu (treasure in people). From 1500 to 1850, a third of the population near the mouth of the Congo River was forcibly relocated through the transatlantic slave trade. Despite the resulting political destabilization, Kongo civilization has thrived within the borders of three Central African states arbitrarily created by colonial powers—Angola, the Republic of the Congo, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo—and across the Americas.

Enslaved individuals carried concepts, such as the cross as a representation of the intersection of the secular and the divine, to the New World. These beliefs developed into religions like Haitian Vodou, in which the deity Kalfou (pictured here) personifies this crossroads.

Kingdoms of the Savanna

New political ideologies shaped a series of influential Central African states that emerged during the first millennium CE. In oral traditions, the development of those institutions over many generations is credited to dynamic, larger-than-life heroic figures. Material traces of these beginnings, in the forms of thirteenth-century chiefly regalia and copper currency relating to ancestral Luba burials, have been unearthed in the Upemba Depression at Sanga in modern-day Democratic Republic of the Congo.

In the epic devoted to the Luba Empire’s founding, the despot Nkongolo was visited by a cultivated hunter-prince from the east, Ilunga Mbili. During that sojourn, the enlightened foreigner married Nkongolo’s half-sister, and their union resulted in the birth of a son, Kalala Ilunga, who would become a formidable warrior. A young Kalala Ilunga spent a formative period learning principles of enlightened leadership in the east before usurping his uncle. The new dynasty he established was defined by the transmission of bulupwe (sacred leadership) through his father’s bloodline.

Kalala Ilunga’s divine lineage played a key role in the foundation of a number of other regional states. The Lunda Kingdom to the southwest traces its origins to the union of its queen, Rweej, with Kalala Ilunga’s son, Cibinda Ilunga. This alliance fostered further adaptation and diffusion of Luba principles of governance to new centers of power developed by the Chokwe, Yaka, and Suku.

Associations along the Upper Lualaba River

By 1000 CE the rise of commerce in copper, iron, salt, and fish within the Congo Basin sparked the formation of an array of voluntary associations. Prerequisites for induction and advancement were membership fees and initiation. Participation afforded prospective members restricted cultural knowledge and affiliation with organizations whose networks extended beyond their immediate communities. Acolytes of bwami, the especially stratified institution developed by the Lega, may pursue a lifelong quest of successive levels of knowledge and erudition. Owners or guardians of bwami artifacts bring them out toto impart their esoteric meaning. On such occasions, they are manipulated in combination with music, drama, dance, and proverbs. At the most introductory level these objects take the form of elements drawn from nature, such as twigs, and culminate with artifacts carved by professionals from ivory, whose significance is revealed only to the most senior bwami members.

Plant Matter and Fashion: Central African Fiber Arts

Foliage from the raffia palm and finely pounded bark have long provided the media for freehand painting, weaving, and embroidery on elite garments across Central Africa. During a fifteenth-century CE visit to the region, Portuguese sea captain Duarte Pacheco Pereira declared Kongo textiles “so beautiful that those made in Italy do not surpass them in workmanship.”

Plain, unadorned squares of woven raffia fiber, or mbala, had value as currency. Their aesthetic elaboration transformed them into priceless originals. While a panel was on the loom, a weaver added supplementary weft fibers and then introduced an additional layer of design and texture by hand-cutting and rubbing those wefts to create a raised pile.

Raffia cloth from the Pende, Kongo, and Mbun was among the novelties introduced by the ruler Shyaam a-Mbul aNgoong (r. ca. 1630–60) at the Kuba court during the early seventeenth century. From his reign on, an original textile motif was selected to inaugurate each dynastic successor. The bwiin (design) served as that individual’s visual signature. Kuba artists hand-embroidered or appliquéd dyed and cut free-form compositions to the surface of plain-woven panels. In overseeing the creation of a monumental garment, a lead designer delegated execution of individual sections to female family members before assembling them within a final composition. Beyond incorporation in sumptuous dress, such labor-intensive fabrics were used in dowry payments as well as displayed as lavish funerary shrouds.

The Kuba Confederacy

The founding sovereign of the Kuba Kingdom (a multiethnic cluster of western Kasai chiefdoms), Shyaam a-Mbul aNgoong was reputedly the son of an enslaved woman. He brought wisdom acquired through travels abroad to the role and is credited with unprecedented change. New crops were adopted, an innovative state structure was instituted, and the splendor of his capital, Nsheng, was augmented through artistic patronage. Every thirty years or so, Kuba sovereigns reenacted the actions of Mboom, the creator god, who laid a woven mat in the sky to define space and establish the cardinal directions. Each new nyim (king) supervised construction of a palace with lushly patterned, woven mat-like walls that provided a rich backdrop for court ceremonies.

Ethiopia’s Holy Bedrock

A concentration of mountains that range from four to fifteen thousand feet above sea level is a defining feature of northern Ethiopia’s landscape. Inspired acts of devotion transformed this terrain into utterly unique sites of worship. From the first millennium BCE, the flow of people between the Arabian Peninsula and the Horn of Africa led to the establishment of trade and the development of towns along the Red Sea. Exchange between the port of Adulis and the city of Aksum became the conduit whereby Christianity was introduced to the Aksumite sovereign Ezana (r. 320s–ca. 380 CE). As early as the first century, the centralization and taxation of commerce allowed Aksum to develop into what the ancient Romans considered to be the third major world power after Egypt.

Monasteries were centers for the production of wall paintings, illuminated manuscripts, and processional crosses for a succession of Christian polities that controlled areas of modern-day Eritrea and Ethiopia. In 1137 CE the center of power was moved south by a new dynasty of Zagwe rulers who made ties with the Holy Land of Palestine by undertaking a massive reconfiguring of the landscape into a new Jerusalem. That sacred topography features a cluster of eleven monumental, rock-hewn churches identified with Lalibela, a Zagwe king and saint who ruled from 1200 to 1250.

Ethiopia’s empire endured into the twentieth century, expanding to encompass Muslims in the eastern Highlands as well as those in southern Oromo and Somali communities. Ethiopia is the only African state to successfully resist European colonization, its emperor becoming emblematic of that independence until Haile Selassie (r. 1930–74) was deposed during a military takeover by the Marxist Derg regime.

The Church of Saint Mary of Zion

King Ezana’s conversion to Christianity and his conquests of neighboring lands are evident in Aksum’s currency. He is depicted on coins with a cross in place of the crescent and disk symbols of earlier religious practices. Aksum’s cosmopolitanism is also reflected in the multilingual inscriptions of ancient Geʿez (an Ethiopian Semitic language), Greek, and Sabean found on the coinage and imposing, state-sponsored stone monuments. From the sixth century CE, all of Ethiopia’s kings and emperors desired to be crowned in Aksum’s Church of Saint Mary of Zion, believed to house the Ark of the Covenant. Between 1527 and 1543, much of Ethiopia was occupied by Ahmed Gragn, a Muslim general and leader of the state of Adal. He led a military jihad in which virtually every church, including Mary of Zion, was looted and razed to the ground.

Southern African Lifestyles

From the eleventh through the nineteenth century, affluence generated from animal husbandry and farming combined with lucrative trade to support the rise of a succession of powerful city-states in southern Africa’s interior. The earliest among these, Mapungubwe in the Limpopo River Basin, channeled animal hides, copper, gold, and ivory to coastal Indian Ocean centers, such as Kilwa Kisiwani, in exchange for glass beads, glazed ceramics, and textiles. As trade routes shifted north in the thirteenth century, the city of Great Zimbabwe emerged as better positioned to supply those networks. The prestige of this capital’s Shona rulers was enhanced by an awe-inspiring royal complex, dramatically integrated into the massive boulders of its hilltop setting through a tour de force of stone masonry.

Toward the end of the seventeenth century, societies further south followed a pastoral lifestyle with an emphasis on cattle-keeping; many of the objects assembled here from this era were designed to be portable. By the nineteenth century, cattle were the primary source of wealth in Swazi, Tsonga, and Zulu communities. In addition to providing milk and meat for sustenance and leather for personal adornment, the livestock served as the basic unit of exchange in bride-price negotiations. Kept in circular izibaya (kraals) around which homesteads were typically organized, cattle were understood as the joint property of the living and their ancestors. Access to cattle and appropriation of grazing lands had been sources of increasingly intense political competition following the arrival of European settlers in the eighteenth century. As urban wage-labor became incorporated into regional economies during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, visual forms associated with a cattle-based culture were extended to growing networks of artistic patronage.

Precursors to Great Zimbabwe: Images of Power in Madzimbahwe (Stone Residences)

In the city-state of Mapungubwe, hilltop burials for ruling elites reflected sharp social divisions between leaders and their constituents. Among the contents later unearthed at these burial sites were gold beaded necklaces and foil-wrapped wood artifacts, including an emblem of power in the form of a rhinoceros. Mapungubwe was abandoned in the twelfth century CE, with hundreds of madzimbahwe emerging as centers that supplied coastal trade through the sixteenth century. Of these cities, Great Zimbabwe (11th–16th century) and Khami (14th–17th century) were among the most influential and economically powerful.

A golden rhinoceros from Mapungubwe, installed alongside a small cache of other royal emblems, including a golden scepter, the University of Pretoria Museums, 2024. Photograph by Thania Louw