Between the late 1740s and early 1790s, the British enamels industry flourished as a result of broader national efforts to stimulate domestic manufacturing, including mercantilist policies (like placing high tariffs on luxury imports) and an investment in technological advancement.[1]

Nearly one hundred enamel objects, recently acquired by The Met as Mrs. Sally Kellogg’s gift of her late husband’s collection, reveal the story of an industry that, though short-lived, gained mass popularity amidst mid-eighteenth-century England’s societal transformations and colonial expansion.

This summer, a selection of these colorful enamel trinkets is arranged inside a vitrine in Gallery 556, dubbed the “Case Study Case” by the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts.

“Case Study Case” on view in Gallery 556 featuring an array of enamel trinkets and related materials. Photo by Rozie Brockington

In England’s primary centers of enamel production—London, South Staffordshire, and Birmingham—these pieces were created by applying enamel colors to a hollow copper core. Steel rollers were first used to flatten copper into thin sheets, which could then be shaped into three-dimensional forms and fired at specific temperatures between the addition of each color.[2]

Transfer printing was the innovation that truly revolutionized British enamel manufacturing. Allowing any engraved image to be applied onto the surface of decorative objects without copying it by hand, transfer printing significantly streamlined the production processes of a wide variety of ceramic goods.

Consumers were intrigued by the novelty of transfer-printed enamels. Famed writer and connoisseur Horace Walpole wrote to a friend in September 1755: “I shall send you…a trifling snuff-box, only as a sample of the new manufacture at Battersea, which is done with copper-plates.” He refers to the York House manufactory at Battersea, founded around 1753, whose enamel boxes have sustained a reputation for exceptional quality—hence the common usage of “Battersea enamels” to describe British enamelware. One of the firm’s founders, John Brooks, has been credited with the invention of transfer printing, though his three patent applications were rejected because the technology was simultaneously being developed elsewhere. Operating for only a few years, the manufactory’s remaining stock was sold at auction in 1756; competing factories purchased unfinished Battersea products, sometimes combining them into hybrid pieces.[3]

Left: Britannia giving coins to Science and the Arts, ca. 1753–56. Enameled copper, 1 3/4 × 2 3/4 × 3 1/2 in. (4.4 × 7 × 8.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Irwin Untermyer, 1964 (64.101.806). Right: Britannia giving coins to Science and the Arts, ca. 1753–56. Enamel on copper, 1 5/8 × 2 3/4 × 3 3/8 in. (4.1 × 6.9 × 8.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. James M. Kellogg, in memory of her husband, 2023 (2023.441.86). Both engraved by Simon Francis Ravenet, the elder (French, 1706–1774), and manufactured by York House (British)

Transfer-printed enamel boxes and plaques made at York House were desirable in part for their unique decoration: in-house engravers designed the images that were then applied to the enamel products. Other manufactories, however, had to source their designs from widely available pattern books and engravings, emphasizing transfer printing’s unique position as a technology at the intersection of the luxury and print industries. Long dominated by European (particularly French) engravings, the British print market began shifting in favor of domestic designers in the mid-eighteenth century.[4] First published in 1760, Robert Sayer’s compiled volume Ladies Amusement: Or, The Whole Art of Japanning Made Easy, became a common source for the adornment of enameled goods.

Jean Pillement (French, 1728–1808). Page from Ladies Amusement: Or, The Whole Art of Japanning Made Easy, 1760. Illustrations: etching and engraving, hand-colored, 7 7/8 x 12 3/8 x 1 1/4 in. (20 x 31.2 x 3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1933 (33.24)

Many enamel boxes were decorated with scenes from ever-popular engravings after French paintings, often by Watteau or Lancret, while others point to temporary trends in the print market. In the 1740s, there was demand for earlier prints by Wenceslaus Hollar, a Bohemian-born mid-seventeenth-century engraver who spent much of his life in London. On March 24, 1743, a printseller named Henry Overton placed a notice in the Daily Advertiser: “Just now reprinted the Plates being carefully clean’d, and printed on very good Paper Several sets and some odd ones of Hollar’s original Prints, much esteem’d by the Curious; the Impressions are very good.”[5] Among these reprints may well have been an engraving depicting two swans, which provided the basis for the decoration of an enameled pink snuffbox. Though the swans appear on this snuffbox’s lid almost exactly as they do in the engraving, new elements—such as the rolling hills and picturesque windmill, potentially from another Hollar print—have been added.

Left: Wenceslaus Hollar (Bohemian, 1607–1677) after Francis Barlow (British, ca. 1626–1704). Two Swans, 1654–58. Etching; second state of two, 5 1/4 × 7 1/2 in. (13.2 × 18.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1917 (17.3.2858). Right: Based on print by Wenceslaus Hollar after Francis Barlow. Snuffbox with pair of swans, ca. 1765–70. Enamel on copper, 1 1/4 × 2 3/4 × 1 5/8 in. (3 × 6.8 × 4.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. James M. Kellogg, in memory of her husband, 2023 (2023.441.69)

The range of objects on view in this case approximates the kaleidoscopic array of luxury goods eighteenth-century shoppers would have encountered upon entering what was known as a toyshop. Specializing not in children’s playthings but in all manner of knickknacks, decorative household items, and personal accessories, a toyshop’s success depended upon enchanting potential customers with mesmerizing displays.[6]

Left: After Jacques Philippe Le Bas (French, 1707–1783), after Nicolas Lancret (French, 1690–1743). Snuffbox with music lesson scene, ca. 1765–70. Enamel on copper, 1 1/8 × 2 7/8 × 2 3/4 in. (2.7 × 7.3 × 7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. James M. Kellogg, in memory of her husband, 2023 (2023.441.67). Center: Bonbonnière in the form of a parrot's head, ca. 1770–80. British. Enamel on copper, 2 × 1 7/8 × 2 3/8 in. (5.1 × 4.7 × 6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. James M. Kellogg, in memory of her husband, 2023 (2023.441.88). Right: Writing Nécessaire, ca. 1765–70. British, South Staffordshire. Enamel on copper, glass, 2 1/4 × 2 3/4 × 1 3/4 in. (5.6 × 6.9 × 4.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. James M. Kellogg, in memory of her husband, 2023 (2023.441.66a–k)

Though made to serve a variety of functions—to carry snuff, candy, or even writing implements—enamel boxes were nonessential purchases, delighting consumers with their whimsy and ingenuity. Enamel trinkets were among the more affordable “toys” on offer, capturing a burgeoning middle-class market.[7] With a similar luster to porcelain, enamel was also an ideal medium in which to replicate more expensive products. A scent bottle in the shape of a gardener with a basket on his head, for example, imitates a design made by the celebrated Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory.

Left: Gardener with grapes scent bottle, ca. 1760. British. Enamel on copper, 3 3/8 × 1 1/8 in. (8.6 × 2.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Irwin Untermyer, 1964 (64.101.810a, b). Right: Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory (British, 1745–1784). Boy gardener, ca. 1760. Soft-paste porcelain, 3 1/2 × 1 1/8 in. (8.9 × 2.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Irwin Untermyer, 1964 (64.101.551a, b)

Negotiating their place in a rapidly evolving society, middle-class consumers were drawn to enameled goods as an affordable means of expressing their refinement and taste. Some of these objects could also convey their owners’ political allegiances. Patriotic sentiments, for instance, were mediated through enamel on both sides of the Atlantic. Celebrating George III’s miraculous (and temporary) recovery from illness in 1789, Britannia appears on the lid of a patch box holding the king’s cameo; she is “proud of her Geo III” and “hopes he will reign many years.”[8] Meanwhile, for the nascent United States, patch boxes were emblazoned with slogans like “American Independence Forever.”

Left: Patch box celebrating King George III’s recovery, 1789. British, Bilston. Enameled copper, 1 × 1 1/2 × 2 in. (2.5 × 3.8 × 5.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Richard B. Seager, 1926 (26.33.4). Right: Patch Box "American Independence Forever," ca. 1790. British, Bilston. Enamel on copper; mirror glass, 1 1/8 × 1 3/4 × 1 3/8 in. (2.7 × 4.3 × 3.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. James M. Kellogg, in memory of her husband, 2023 (2023.441.47)

Some contemporaries contemplated the hidden costs of the inexpensive consumer goods that were flooding the British market. The Scottish philosopher and economist Adam Smith, in his Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759), dwells on how the perception of functionality can conceal the superfluity of desirable commodities:

How many people ruin themselves by laying out money on trinkets of frivolous utility? What pleases these lovers of toys is not so much the utility, as the aptness of the machines which are fitted to promote it. All their pockets are fluffed with little conveniencies [sic]. They contrive new pockets, unknown in the clothes of other people, in order to carry a greater number.

An enamel bonbonnière in the form of a woman’s bust beautifully illustrates Smith’s point. Not only does a hinged lid below her striped bodice reveal a compartment ideal for storing lozenges, but a metal tube inside her head contains a glass scent bottle. Ostensibly fulfilling two distinct purposes, such an item Smith maintains “might at all times be very well spared…[its] utility is certainly not worth the fatigue of bearing the burden.”

Bust of a woman bonbonnière and scent bottle, ca. 1775. British. Enamel on copper, glass, 3 1/8 × 2 1/8 × 1 5/8 in. (7.9 × 5.2 × 4.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. James M. Kellogg, in memory of her husband, 2023 (2023.441.28a–c)

Referring to the literal weight of a pocket filled with countless baubles, Smith’s use of the word “burden” might also be considered, following Iris Moon’s “between the lines” reading in Melancholy Wedgwood (2024), as a “meditation on the emotional aftereffects of material accumulation.” As Smith would go on to explicitly argue in The Wealth of Nations (1776), his seminal economic publication, labor was the ultimate cost of commercial success.

Pair of tea caddies (part of a set), ca. 1765–70. British, South Staffordshire. Enamel on copper, 4 1/4 × 3 × 2 3/8 in. (10.8 × 7.6 × 6.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. James M. Kellogg, in memory of her husband, 2023 (2023.441.37a, b, .38a, b)

As the conquests of expanding colonial empires brought foreign commodities like tea, sugar, and nutmeg into European markets, specialized objects for their consumption were produced in enamel. Tea caddies, sugar boxes, and nutmeg graters could function as potent symbols of Britain’s prosperity.

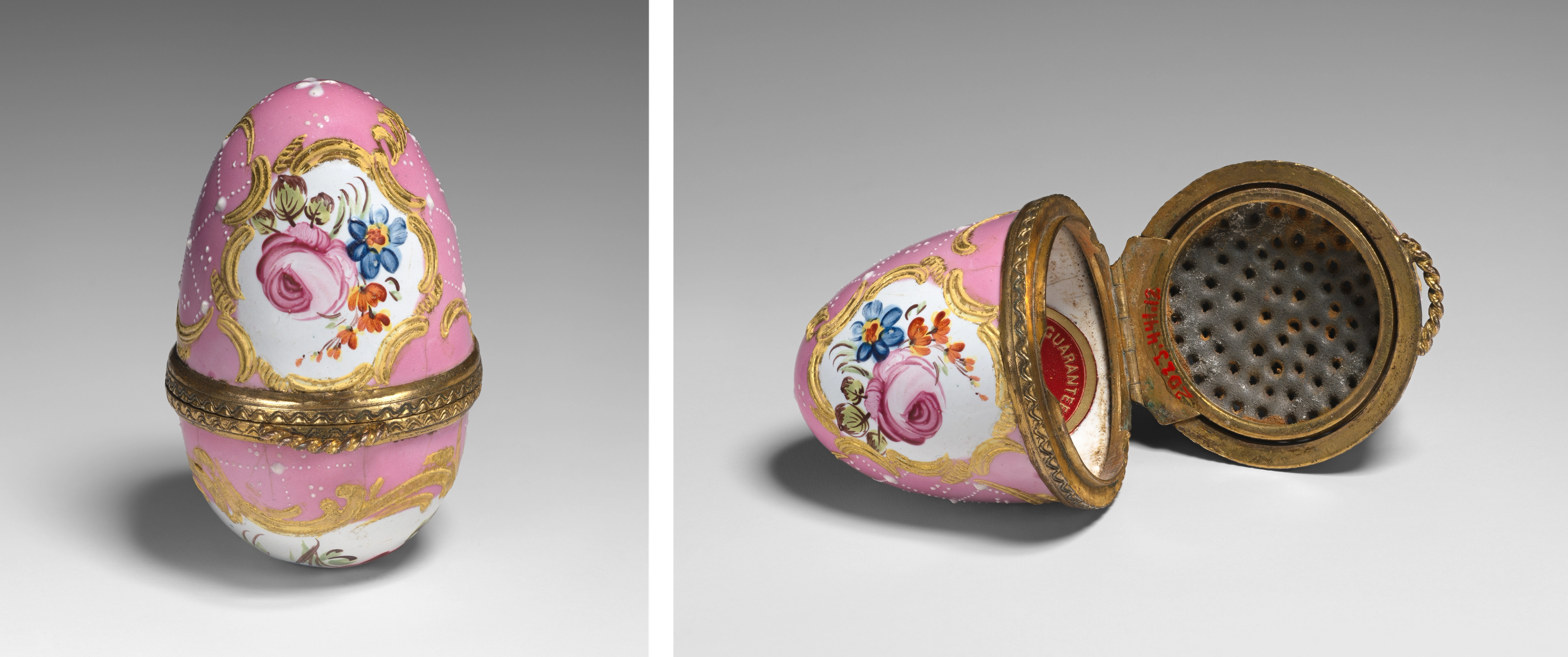

Nutmeg grater, ca. 1765–70. British. Enamel on copper, 2 1/8 × 1 3/8 in. (5.3 × 3.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. James M. Kellogg, in memory of her husband, 2023 (2023.441.12)

Of course, British access to these goods was predicated on the exploitation of foreign resources and labor. Nutmeg, transported in tiny egg-shaped containers fitted with metal graters, originated in the Banda Islands (called the “Spice Islands” by Europeans) in today’s Indonesia. The Dutch, vying for a monopoly on the lucrative nutmeg trade, killed or enslaved ninety percent of the Bandanese people in the seventeenth century. One of these islands, Rhun, remained under British control until 1667, when it was famously relinquished to the Dutch in exchange for the island of Manhattan.

Based on print published by Robert Sayer (British, 1725–1794). William Beckford (1709–1770), ca. 1769–70. Enamel on copper, 4 1/2 × 3 3/8 in. (11.4 × 8.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Irwin Untermyer, 1964 (64.101.807)

Sugar came to England from plantations in the British West Indies, where it was grown and harvested by enslaved African laborers. William Beckford, depicted on an enamel plaque during his second term as mayor of London, was the greatest Jamaican landowner in 1754; even a decade earlier, nearly one thousand enslaved people farmed his substantial plantation holdings.[9]

Having established a reputation for championing the mercantile interests of the middle classes, Beckford was evidently popular enough for his likeness to be reproduced on decorative objects. Walpole, however, sardonically remarked in 1762: “Beckford is a patriot, because he will clamour if Guadeloupe or Martinico is given up, and the price of sugars fall. I am a bad Englishman, because I think the advantages of commerce are dearly bought for some by the lives of many more.”

Hot water jug, ca. 1760. British. Enamel on copper, 9 3/8 × 5 in. (23.8 × 12.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. James M. Kellogg, in memory of her husband, 2023 (2023.441.1)

Consumables acquired through labor and violence abroad could be contained within enameled goods created by intricate networks of labor far closer to home. Unusually large for an enamel object, this hot water jug was used to refresh brewed tea at the table. A seam around the middle of the body, visible despite its cohesive white enamel coating, suggests that the copper base combines two separate hollow forms. This copper was likely obtained from a Staffordshire mine, where, in 1769, more than three hundred people worked grueling hours for low wages.[10] An experienced enameler, or group of enamelers, then decorated this jug, delicately hand coloring its ancient vistas and surrounding them with intricate, raised ornamentation. Yet another craftsperson, employed elsewhere, would have made the metal mounts connecting the body to the lid and articulated spout.

More than two centuries later, their handiwork continues to delight. Though valued first and foremost for their charm, these little luxuries surface discourse about consumerism, exploitation, and nationalism that reverberate into the present day.

Notes

[1] Susan Benjamin, English Enamel Boxes (New York: The Viking Press, 1978), 23; Therle Hughes and Bernard Hughes, English Painted Enamels (London: Country Life Limited, 1951), 86; Maxine Berg, Luxury and Pleasure in Eighteenth-Century Britain (Oxford University Press, 2005), 92.

[2] For a detailed explanation of the enameling process, see Benjamin, 30-37.

[3] Benjamin, 41; 44-45.

[4] Timothy Clayton, The English Print 1688-1802 (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1997), xii.

[5] Clayton, 169., fn. 52.

[6] Trevor Fawcett, “Eighteenth-Century Shops and the Luxury Trade,” Bath History 3 (1990): 65, 73-74. For more on toyshops, see also Vanessa Brett’s Knick-knackery: The Deards Family & their Luxury Shops 1685-1785 (2023).

[7] Benjamin, 9.

[8] Dyer, Serena. “Portable Patriotism: Britannia and Material Nationhood in Miniature.” In Small Things in the Eighteenth Century: The Political and Personal Value of the Miniature, edited by Chloe Wigston Smith and Beth Fowkes Tobin (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022), 240.

[9] Perry Gauci, William Beckford: First Prime Minister of the London Empire (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2013), 147; 44.

[10] Benjamin, 30.