When I was young, one of my favorite books was Gone-Away Lake (1957) by Elizabeth Enright. The novel follows two young cousins, Portia and Julian, who discover a Victorian community of summer houses, all but one abandoned decades before when the lake at the center dried up. The cousins, after befriending the elderly siblings who still reside there, spend their leisurely summer days exploring the abandoned houses, running from room to room—each one frozen in time—and opening cabinets and cupboards to find old toys and dresses and tea sets and books, and hearing the stories of the long-departed former residents who occupied these spaces. This was my “summer book,” which I retrieved from the shelf annually when school let out for the break, eager to return to this place—these houses and rooms brimming with treasures and stories, waiting to be uncovered. It was, in a way, a kind of summer home itself: slightly musty, full of cobwebs and dust to be cleaned away upon arrival, familiar but also exciting and full of promise. I can distinctly recall the sensation of lifting the book’s front cover and feeling that it was not a flimsy piece of cardstock but a front door, swinging on squeaky hinges and emitting a burst of cold, stuffy air, opening to welcome me back.

The idea that a book contains, represents, or allows access to a physical space is not uncommon. In his 1974 essay “Species of Spaces,” experimental writer Georges Perec begins by presenting the page as a space, then transforms the page into a bed, a bedroom, an apartment, a building, a street, and so on. As readers, we progress through these spaces, which expand with the text and our movement through them.

I’ve been dwelling on the idea of the book as a house ever since I treated and rehoused a large group of children’s books held in the Department of Drawings and Prints from 2022–2023 under the support of a New York State Library grant. This collection included a toy book, Das Puppenhaus, Eine Festgabe für brave Kinder [The Doll’s House, a Gift for Good Children] (ca. 1890).

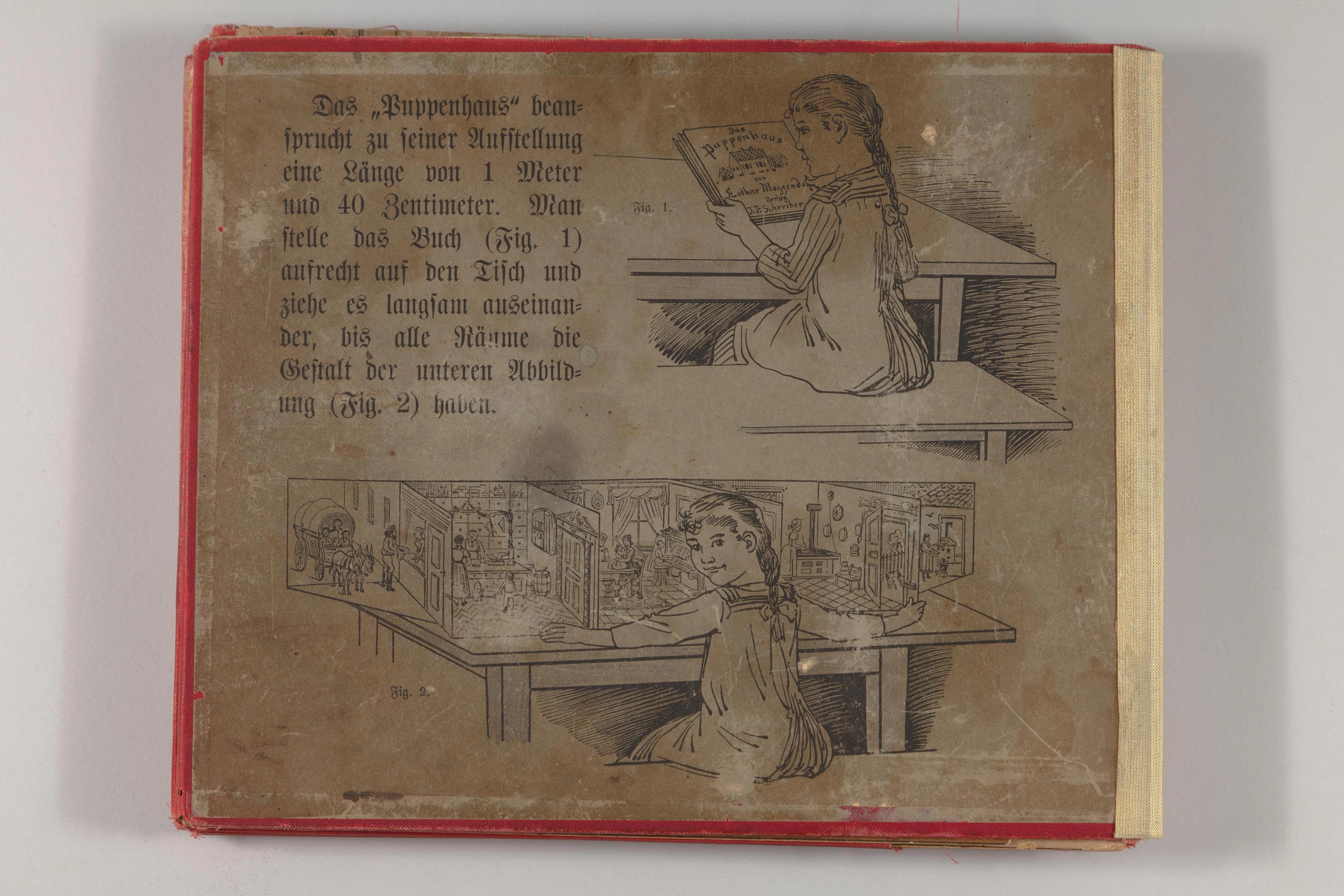

The back cover, which shows a girl with the fully opened house-book, in Lothar Meggendorfer’s Das Puppenhaus, Eine Festgabe für brave Kinder, ca. 1890, published by J. F. Schreiber. Germany, Stuttgart. Color lithographs, 8 1/2 x 10 1/4 x 1 in. (21.5 x 26 x 2.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Waldo Henley Hunt, 1978 (1978.559)

Constructed from paper and board, each of its pages has flaps that open to form a three-dimensional room, populated with pop-up figures and furniture. Within the paper walls there are paper doors that actually open, creating a path from one space to the next. How thrilling it must have been for young readers to navigate its colorful pages, each forming a space in which one could play, daydream, or tell stories.

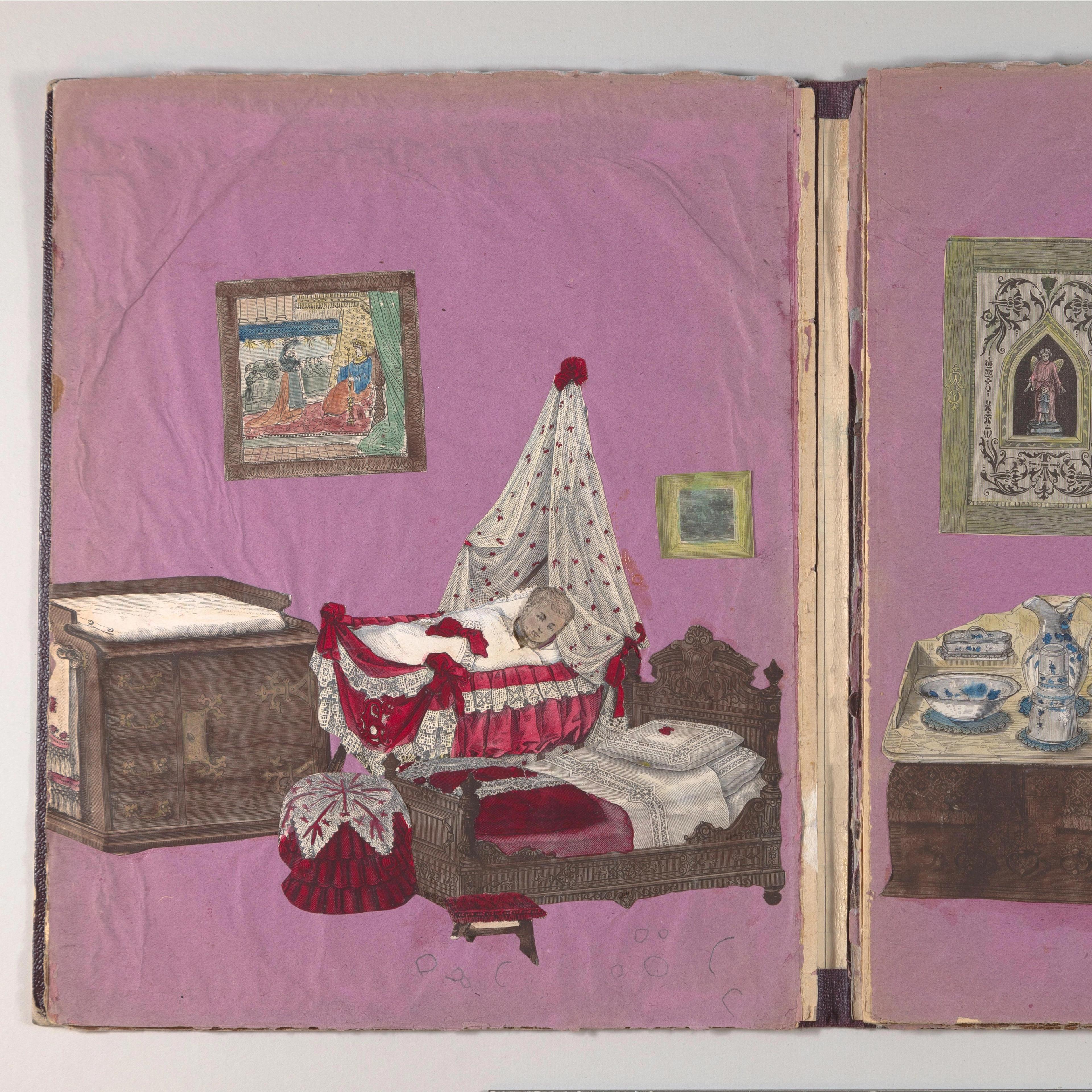

Page opening with pop-up figures and furniture in Lothar Meggendorfer’s Das Puppenhaus, Eine Festgabe für brave Kinder.

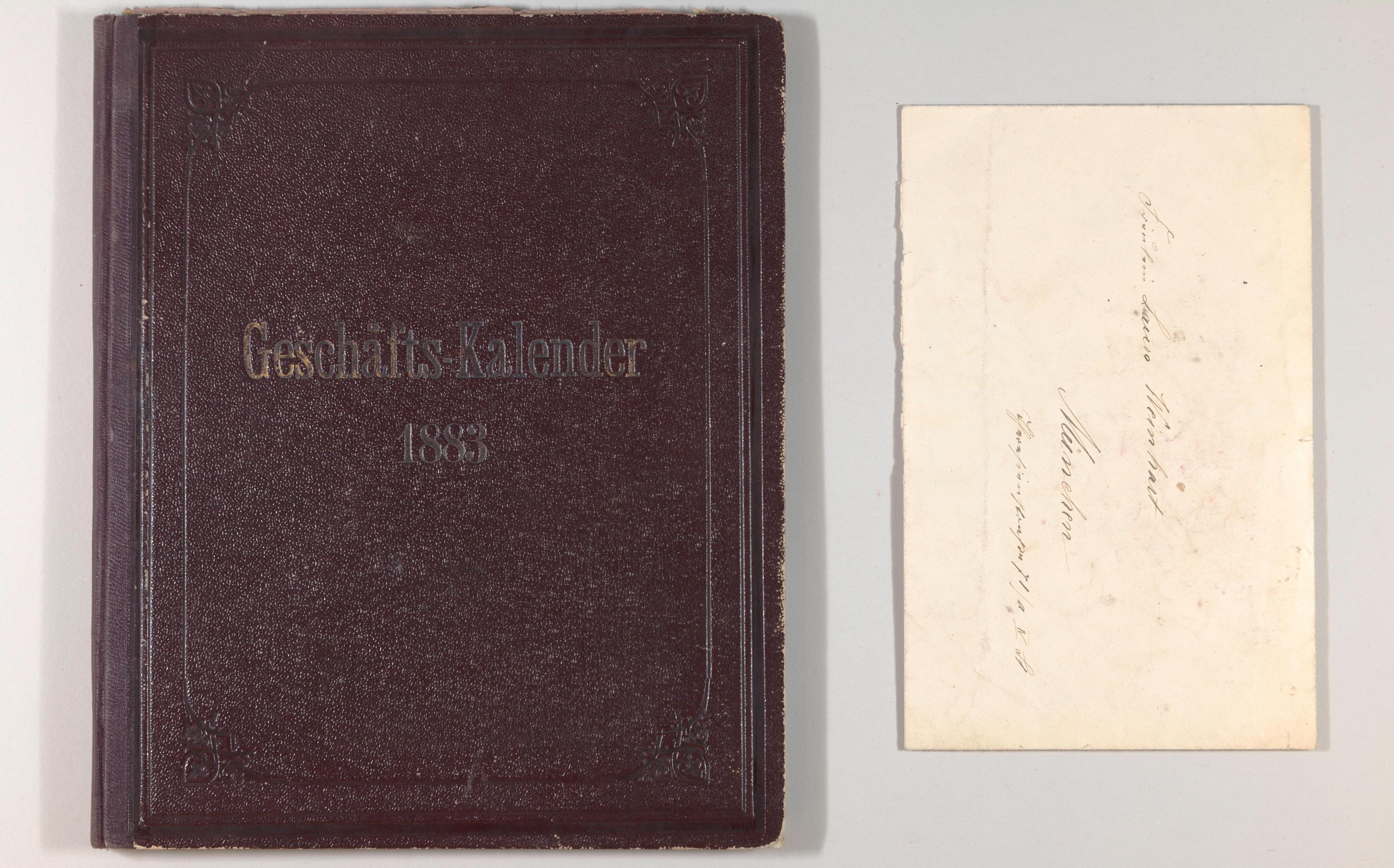

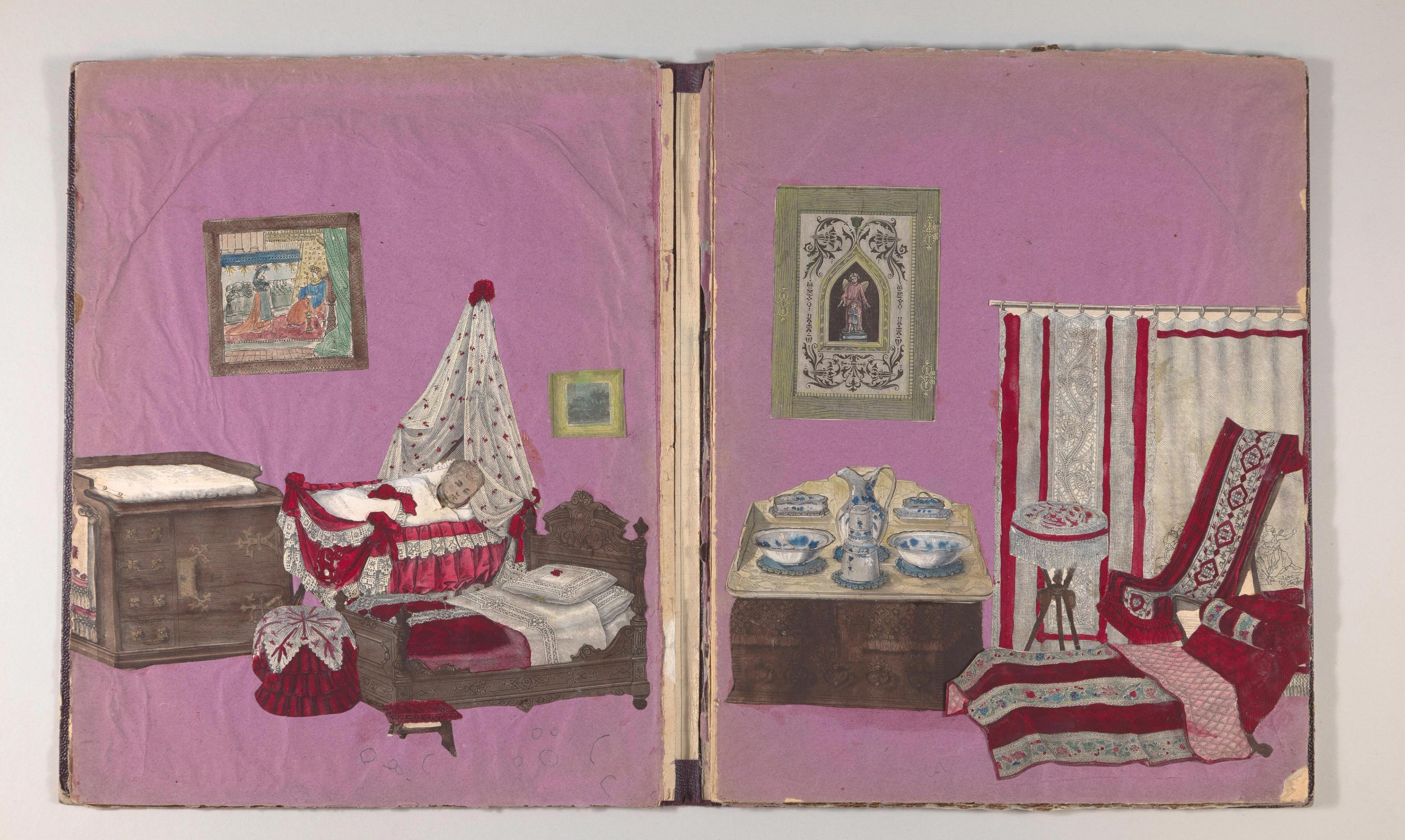

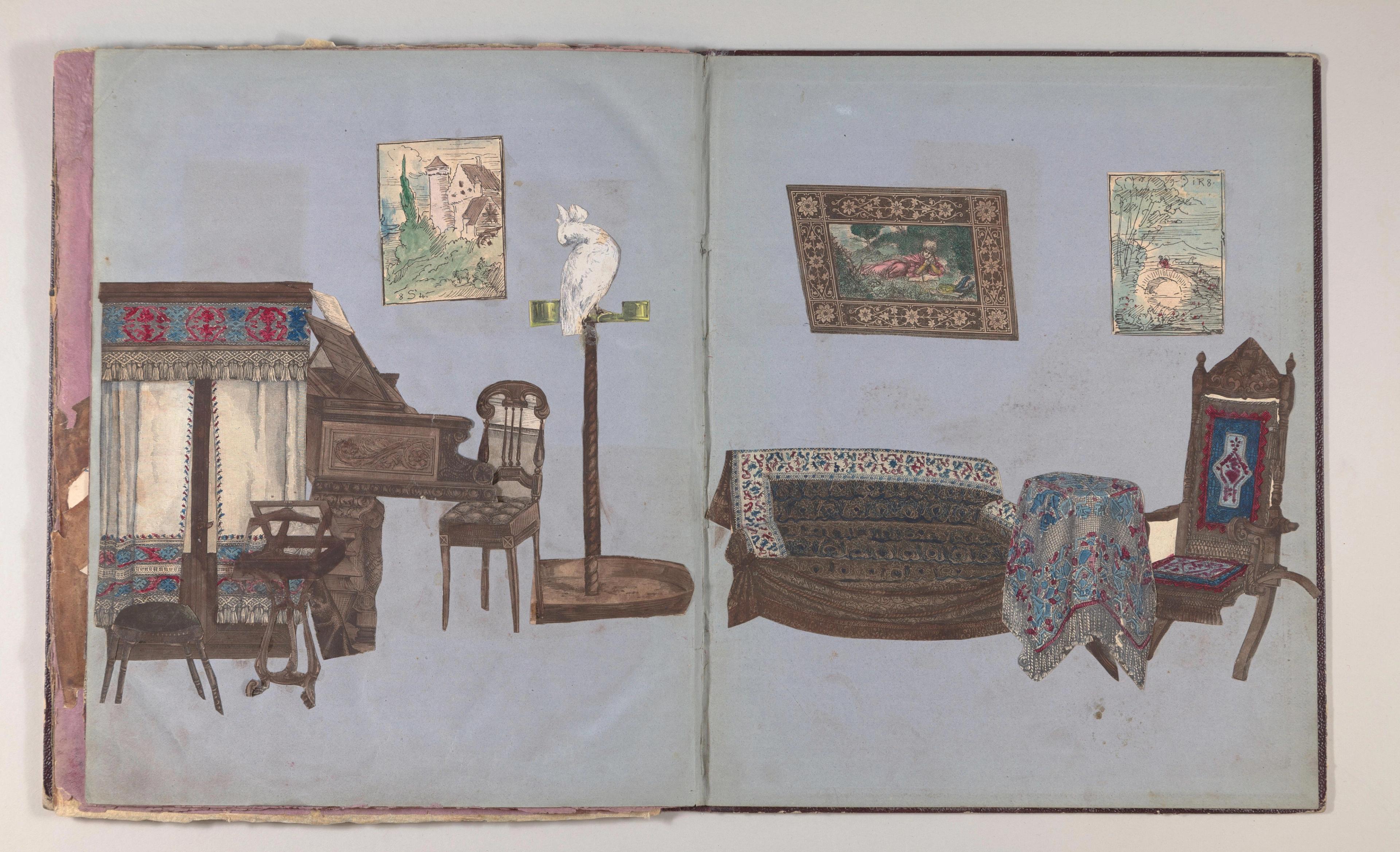

But the book that really made my heart sing was a handmade album in which each page spread—hand-collaged with cut-out printed paper furniture, windows, picture frames, and wallpaper—becomes a room to house a set of accompanying handmade paper dolls. Though the album is cataloged by an anonymous maker, the name “Fraulein Laura Weinhart” is inscribed in an elegant hand across the front of the envelope that holds the paper dolls, suggesting that a young German girl created, and perhaps played with, the album. Its German origin is confirmed by the stamped text on the repurposed binding that holds the album pages: “Geschäfts Kalendar 1883” [“Business Calendar, 1883”].

The cover of the re-purposed bookbinding, with the accompanying inscribed envelope that holds the paper dolls, of Paper doll house album: “Geschäfts-Kalendar für 1883”, 19th century. German. Wood engravings, printed paper, cut out, hand colored and assembled, 11 x 9 1/8 x 3/8 in. (28 x 23 x 1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Lincoln Kirstein, 1970 (1970.565.136(1-8))

As I spent time examining and treating this album, I couldn’t help but imagine scenes from its creation. Scholarship about late nineteenth-century collage, scrapbook practice, and paper dolls, supports the idea that the creator of this album would have been a young woman. I envision, though cannot confirm, that the repurposed calendar—business-like not only in title but in design, with its brown stamped-cloth cover, upright font, and restrained, blind-stamped ornament—was given to her by her father once it was no longer in use, and that she then carefully removed the filled-up pages by cutting along the inner text-block joints. She created new pages with material that might have been sourced from around the home, too, pasting together sheets of recycled printed paper, colored paper, and pieces of wallpaper to form new leaves, each becoming the backdrop for a different room.

In this bedroom scene from Paper doll house album, there is a slit cut into the cradle’s blanket, allowing the baby’s head (affixed to a paper tab with a dab of wax) to be inserted and removed.

In another bedroom from Paper doll house album, the beds were drawn and colored by hand in washes of blue and red.

To fill the rooms, the album’s architect carefully cut out printed paper furnishings, likely from magazines or catalogs, as indicated by the text on their backs. (Many of the furnishings—tables, chairs, blankets on beds—are only partially adhered so that paper dolls can be inserted inside or behind them, which conveniently allows for a peek at the printed verso.) In addition to furniture, the rooms include cut-out pictures on the walls, a fireplace with candlesticks and a fan arranged on its mantel, screens, vases of flowers, and even a bird in a cage—sometimes in different perspectives, which causes a slightly dizzying effect. The creator of the album hand-colored the black-and-white furnishings in washes of brown, red, and blue, and, when an item was not available, drew it by hand.

In this collaged room from Paper doll house album, the chairs at left and the tablecloth at right are only partially adhered to the page, allowing them to be lifted for paper dolls to be placed within the scene.

Paper dolls, like the furniture, appear to have been cut from printed media, and are cleverly constructed; assorted heads, affixed to paper tabs, can be stuck to the garments with small dabs of wax (or, disembodied, inserted into the scenes without clothing, like the baby in the bedroom cradle).

The contents of the envelope from Paper doll house album include various paper heads, garments, and accessories. The versos of the paper doll elements, printed with text or fragments of other images, suggest that they were cut from print publications.

This album also reveals a history of frequent handling, allowing us to imagine its user actively engaging it in play. Besides overall soiling, the paper leaves, furnishings, and dolls’ garments are creased and torn along the edges. Like a house, it was gut renovated and built anew from within, and then the spaces and characters came to life, activated by the hands that created them.

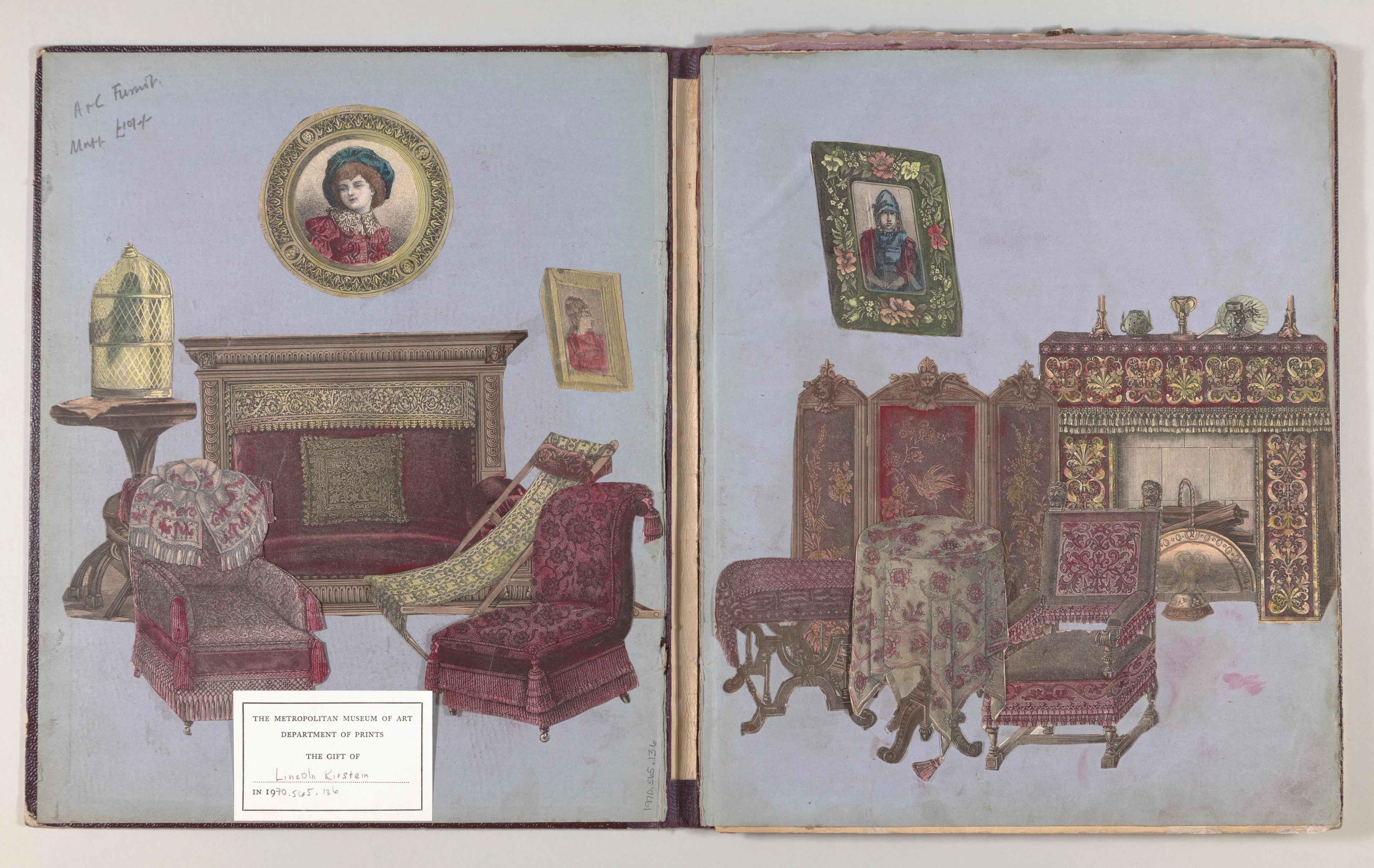

Nearly two years after working on the paper-doll house, I stumbled upon Collage album, not before 1870 (ca. late 19th century), another house-like album, this one from Boston and in the Watson Library’s collection. Like the German paper-doll-house album, its paper rooms are built up with collaged, cut-out elements. While the German paper-doll house might represent an instance of fairly unique production—I was unable to find much scholarship about or other examples of late nineteenth-century German scrapbook houses—Collage Album is an example of a more widespread craft practice, one of many scrapbook forms that were common pastimes for American women of all ages in the Victorian era.

Most of the rooms in Collage album, not before 1870 are oriented horizontally on the righthand page, with remnants of the album’s former contents on the lefthand page. In the room shown here, collaged dishes are placed on a hand-drawn table, reused wallpaper forms a carpet, and strips of blue paper delineate the space of the room.

Unlike the German doll-house album, the American house albums did not serve as backdrops for imaginative doll play, but were the end goal in and of themselves, educating young women in both the precise hand skills of careful cutting and pasting, as well as in the decoration and maintenance of the domestic sphere.

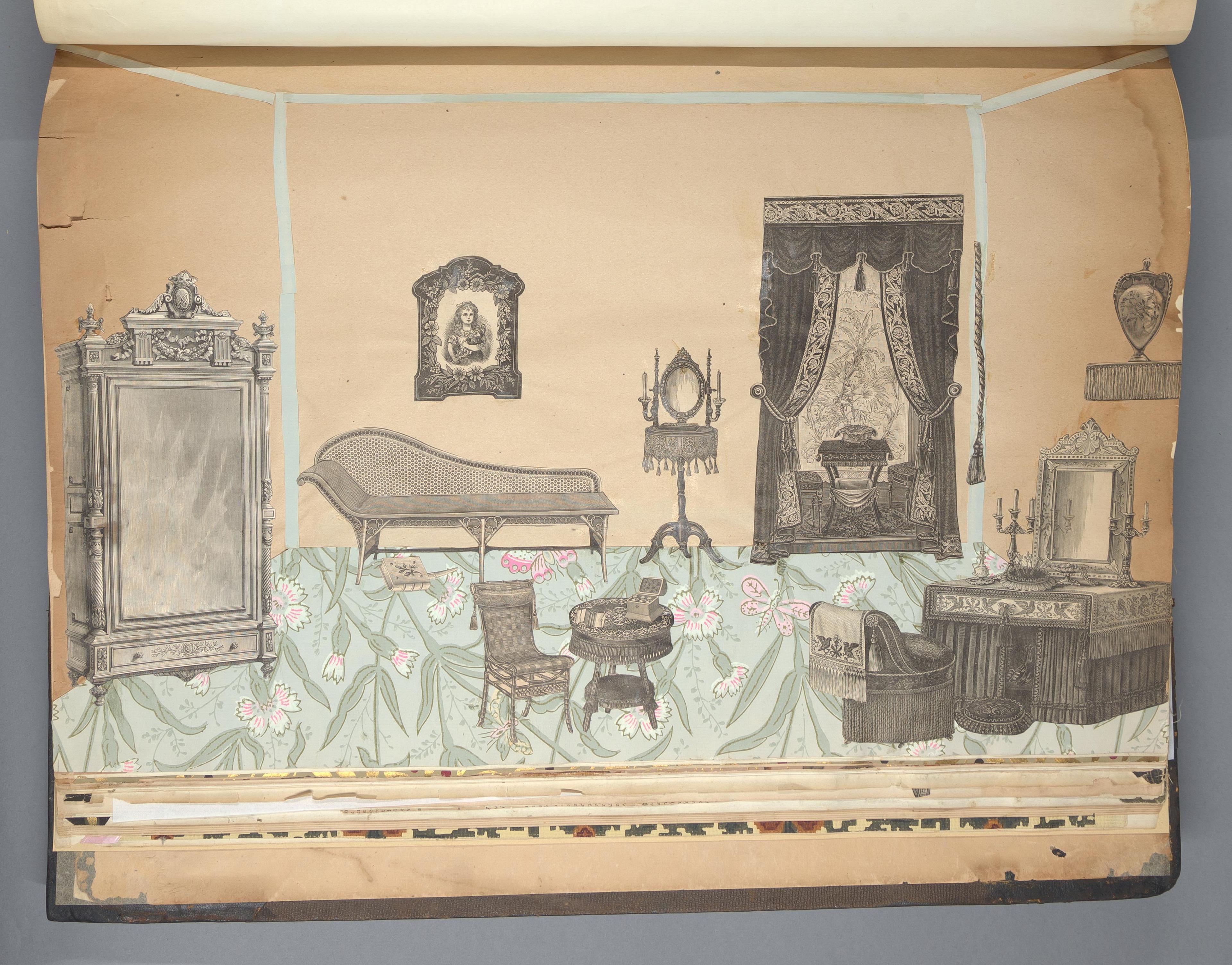

This large house album in Watson’s collection includes an impressive number of rooms—a front hallway, multiple sitting rooms, a playroom (which contains its own doll house, with miniature collaged rooms within), a picture gallery, and more. On the occasional blank page, we see the names of other rooms inscribed in ink, indicating that its maker had further plans for interior designs that were not completed. (One blank page, for instance, is labeled “servants sitting room.") In all the finished rooms, we see a delightful mixture of collaged and hand-drawn elements; with a ruler and pencil, the album’s creator delineated the floor, ceiling, and walls of each room, as well as doorways, window frames, and other architectural elements.

Strips of stamped, gold paper were used to make a picture frame, and cats and a loose parrot coexist peacefully in Collage album, not before 1870.

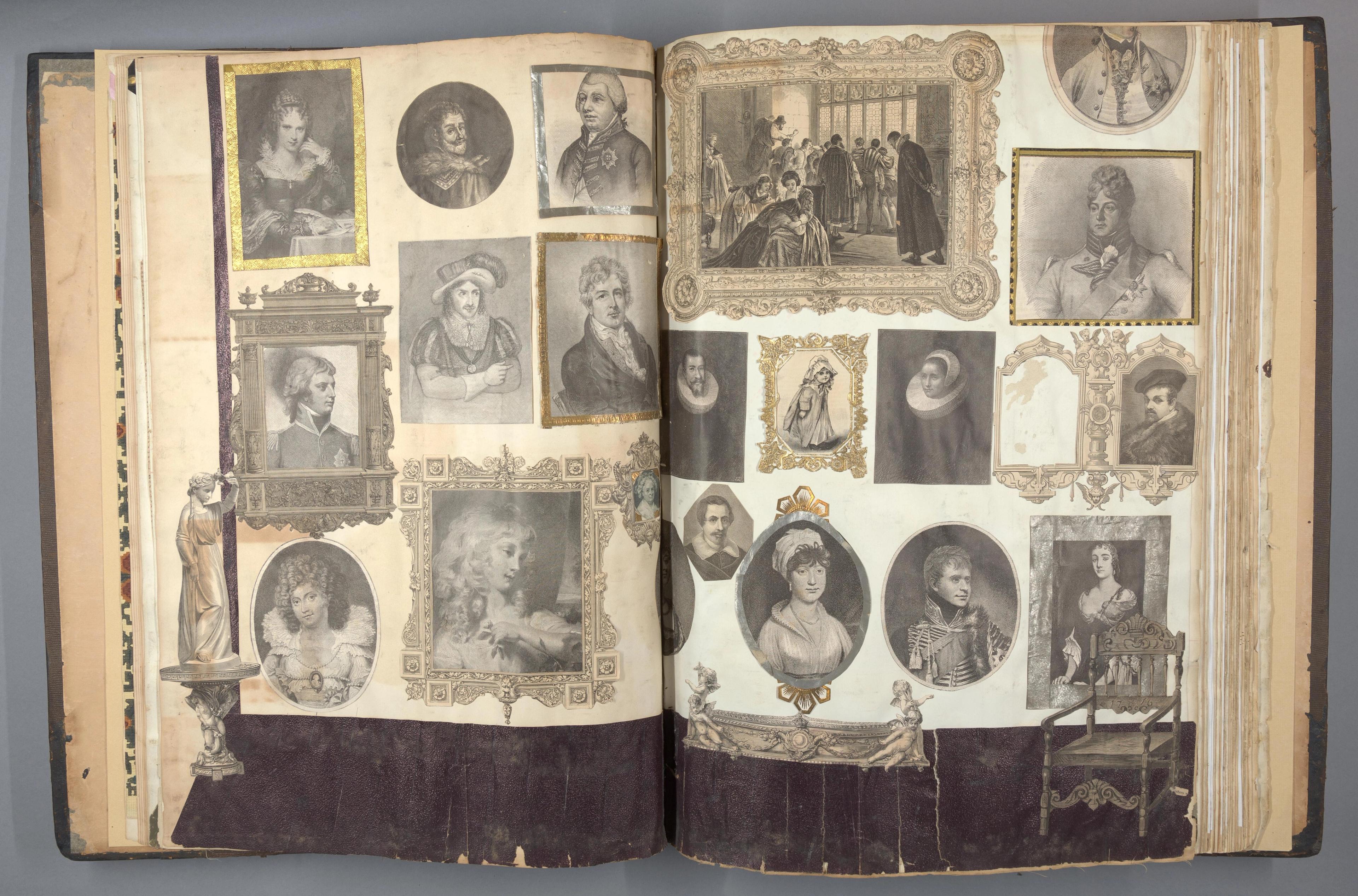

Furnishings, primarily left in black and white with occasional hand coloring, appear in a variety of styles and scales: chairs, tables, vases, toys, musical instruments, sculptures, and decorative screens abound. In what appears to be a picture-gallery room, framed images crowd the wall, some in makeshift frames constructed out of stamped silver and gold papers; one, cut off at the middle, even extends beyond the edge of the page.

Towards the end of the album, the collaged rooms shift to a vertical orientation and begin to span both pages. Here, a variety of printed portraits are adhered within either printed paper frames or gold paper frames to form a densely hung picture gallery.

The different perspectives in which the bed and other items of furniture are rendered create a rather dizzying viewing experience.

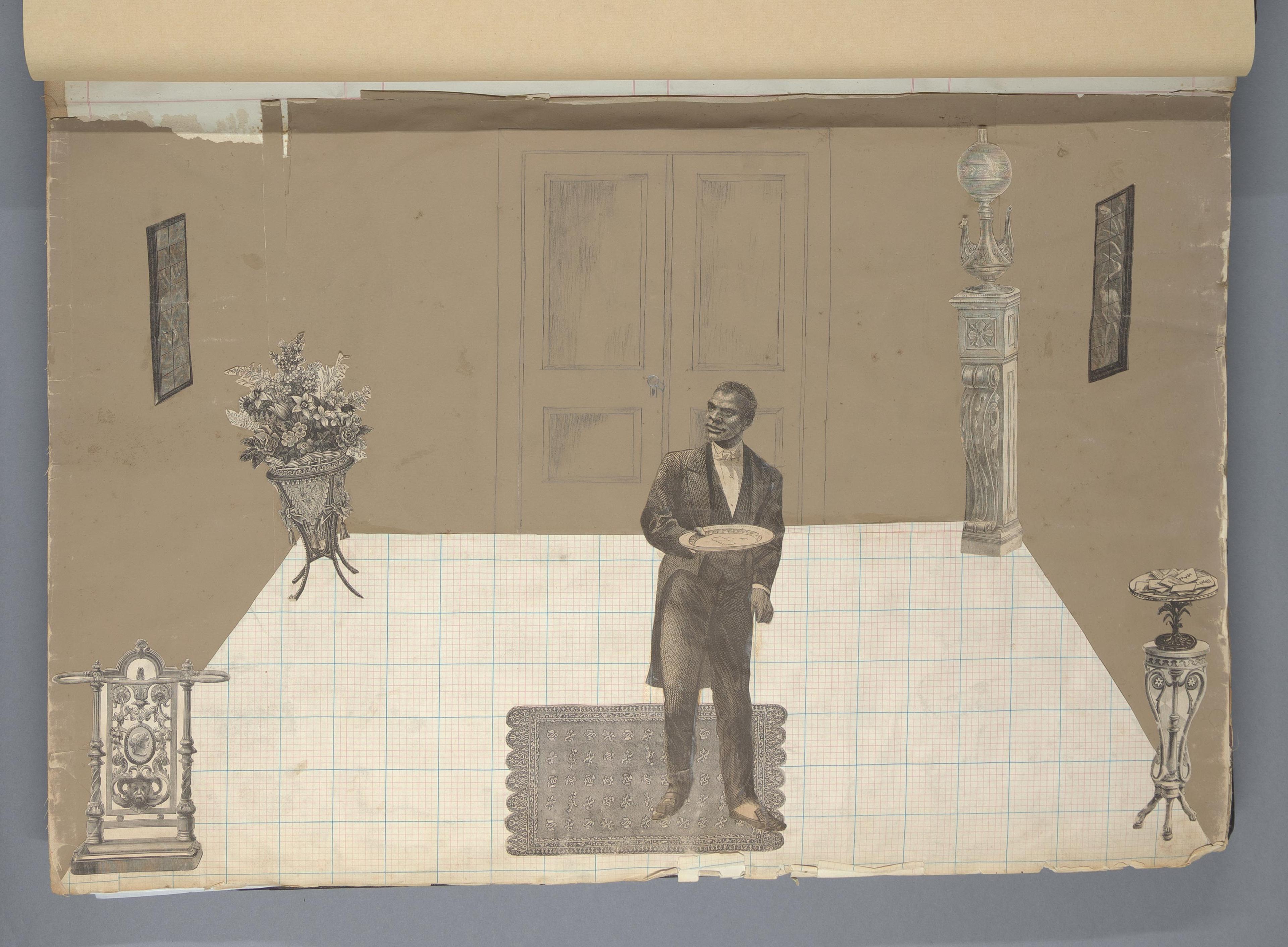

To add some brightness to the rooms, the maker used decorative papers or wallpaper samples, some printed with gold, as carpeting, and strips of colored or gold paper as ceiling and floor molding. In comparison to the paper-doll-house album, this one feels a bit lonesome, as it is mostly devoid of human inhabitants. In the children’s room, we see a few figures (though some might be large dolls), and in the front hallway, a Black servant waits with a tray in hand, suggesting that the album’s maker may have viewed domestic staff as more equivalent to furniture than as living occupants.

A child’s playroom includes a doll house—a house within a house—constructed of cut white paper and graphite lines, printed images of rooms or collaged scenes of tiny furniture; toys and dolls in a variety of illustrated styles; and even a miniscule copy of a book (What Katy Did) in a publisher’s binding that can be dated to 1883.

Against a grid paper floor and hand-drawn door a butler stands at the ready with a tray in hand—the only human figure included in the album.

Especially interesting is the fact that this album, like the paper-doll-house book, was created within a repurposed binding structure—here, making use of an emptied-out sample book which, as indicated by fiber fragments still adhered to splotches of glue, appears to have formerly held textile samples. These two instances of reuse suggest something about the value and availability of books like stationery bindings; once filled or no longer useful, they were not discarded but recycled, rebuilt, and used anew.

Perhaps, too, there is an inherent connection between these types of books—calendars, blank books, diaries, all meant to record or organize information—and the space of the home. Gaston Bachelard writes in The Poetics of Space (1958): “Of course, thanks to the house, a great many of our memories are housed, and if the house is a bit elaborate, if it has a cellar and a garret, nooks and corridors, our memories have refuges that are all the more clearly delineated. All our lives we come back to them in our daydreams.” Bachelard suggests that we require concrete places in which to fix our memories. Certain types of books literally provide this space, offering up blank pages to record the activity and thoughts of one’s life. These house albums—rich illustrations of domestic spaces, of the play and education of girls and young women, a record of the material goods both desired and available—might also be seen as representative of the figurative space of memory, allowing the viewer to find a home in a good book.