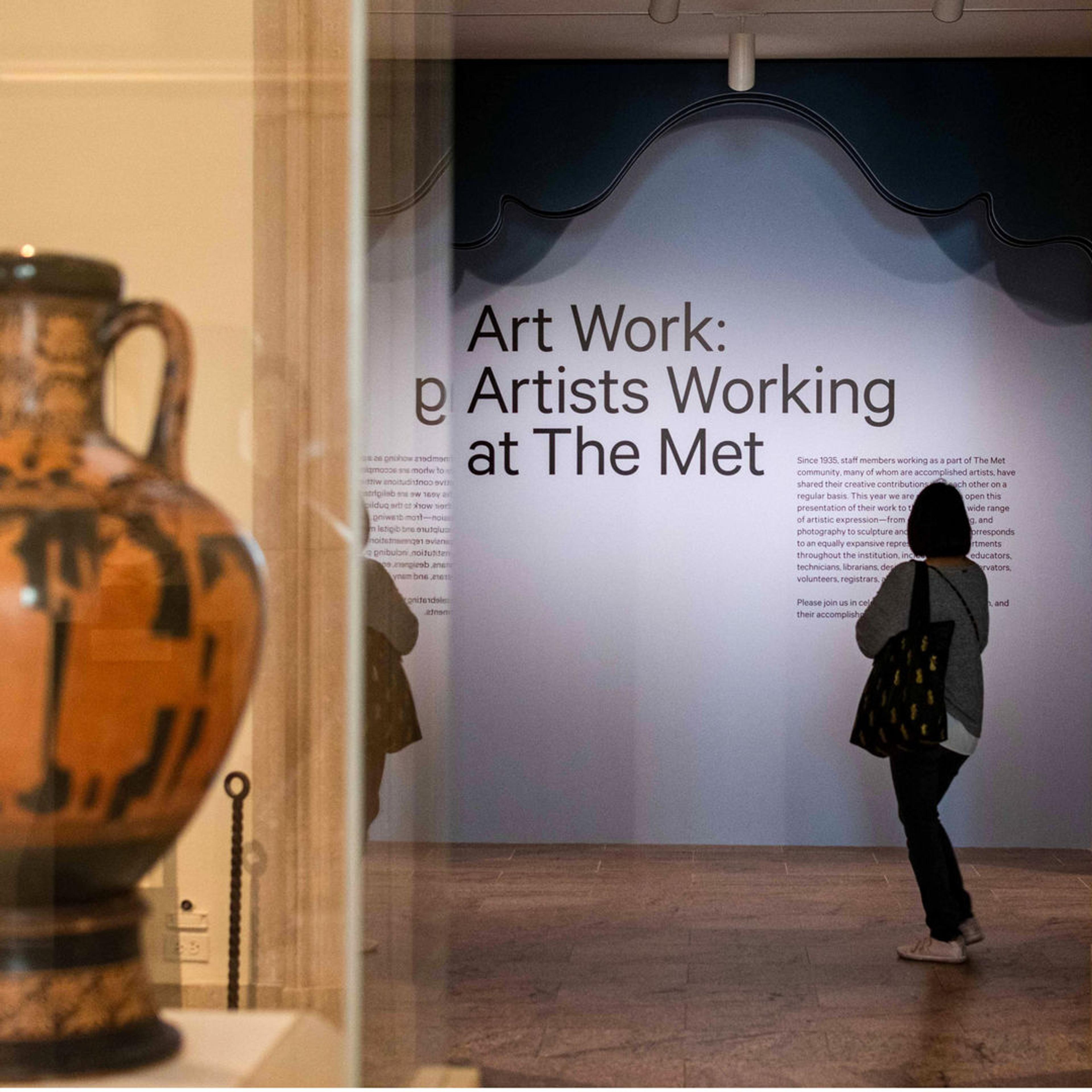

Since 1935, The Met has held a biennial exhibition of artwork submitted by staff from departments across the Museum. This year, for the first time, the show is open to the public, with visitors happily lingering in front of images and objects that move and inspire.

Since the exhibition Art Work: Artists Working at The Met has no catalogue and minimal wall text, we decided to seek out stories from a selection of the artists to learn more about their creative lives and their reasons for making the work they have so generously shared.

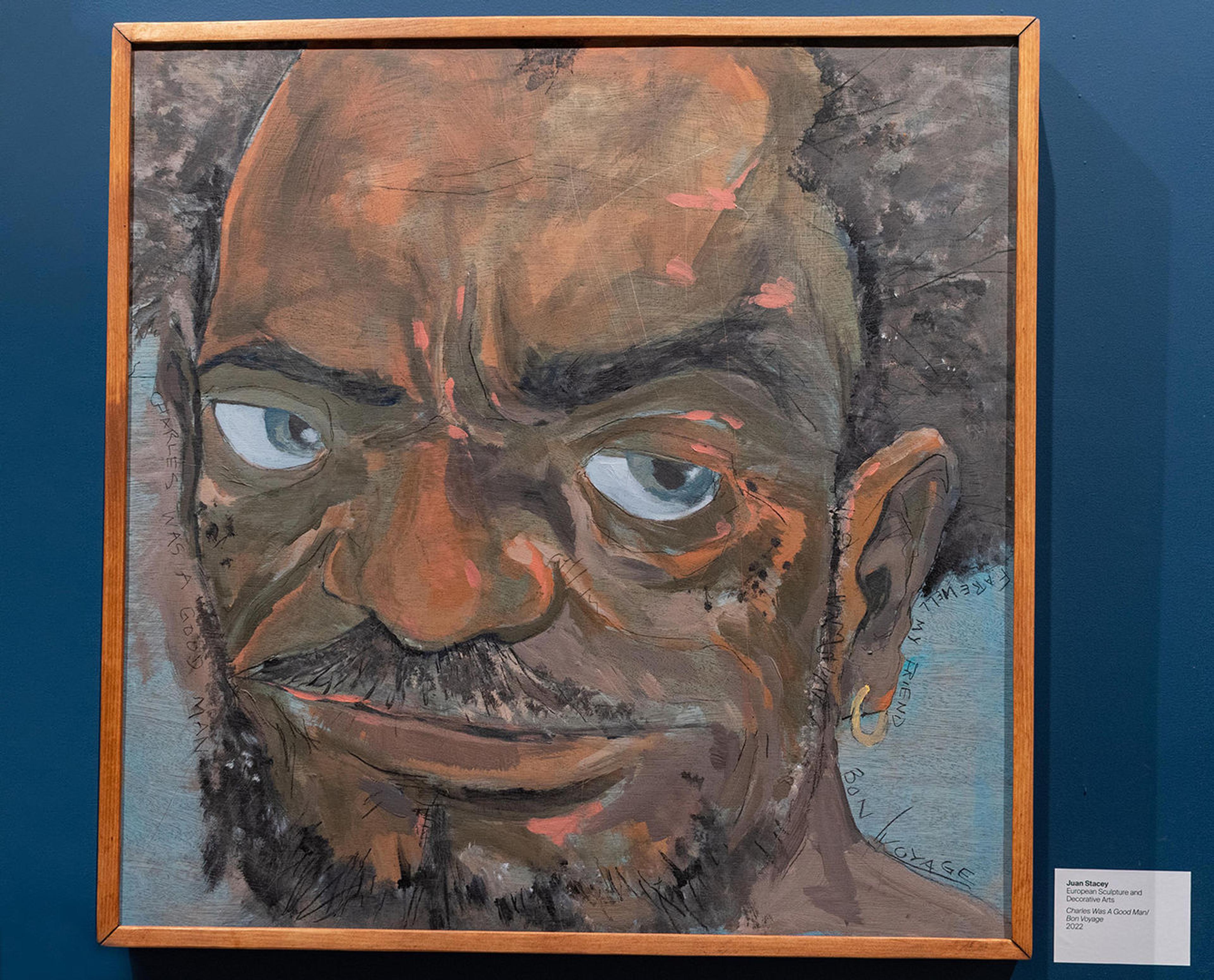

Juan Stacey, Charles Was A Good Man / Bon Voyage (2022)

Juan Stacey. Charles Was A Good Man / Bon Voyage, 2022. Photo by Aurola Wedman Alfaro

My painting, Charles Was A Good Man / Bon Voyage was created earlier this year in homage to Charles Dixon III, previously a Met technician for the Department of Islamic Art who sadly passed away last year. My art is concerned with memory, and the difference between recollection and reality; for many years now I’ve done portraits of individuals from my past, strictly from memory, without any other visual reference. I’m fascinated by the differences between how a subject actually looked versus my portrayal of them, how I see them in my mind’s eye. It was my intention to get across some of Charles’s sardonic humor and his impish personality, all the while not undercutting the mournful aspect of his passing. Hopefully a viewer looks at the painting and sees not just a technically skilled representational work, but also gets a sense of some of the underlying pathos that went into it.

Although I went to school for visual art, for the past two decades I’ve primarily been working in the medium of music. The origin of this painting, and why it’s a painting at all, goes back to another former museum employee, Toma Fichtner, previously of the Ratti Textile Center and now the owner of Chinatown gallery 201@105. Earlier this year Toma curated a memorial show dedicated to Charles. While I wrote and recorded music to mark his passing, I also felt inspired to do a visual companion piece. My work is mixed media, primarily acrylic paint and charcoal on panel. Acrylics are wonderful because of the speed and precision they lend to the process, as opposed to the more loose and long-term working required by oils. Working on wooden panels gives an organic quality that I love, and it also allows me to sand and scratch the surface, something that I’ve also done with this work. The wood grain and abrasions make the painting feel both alive and lived-in. I frequently use text in my work to reinforce ideas and themes; in this case, the text comes from the closing line of the companion song I wrote for Toma’s memorial show: “Farewell my friend, and bon voyage.”

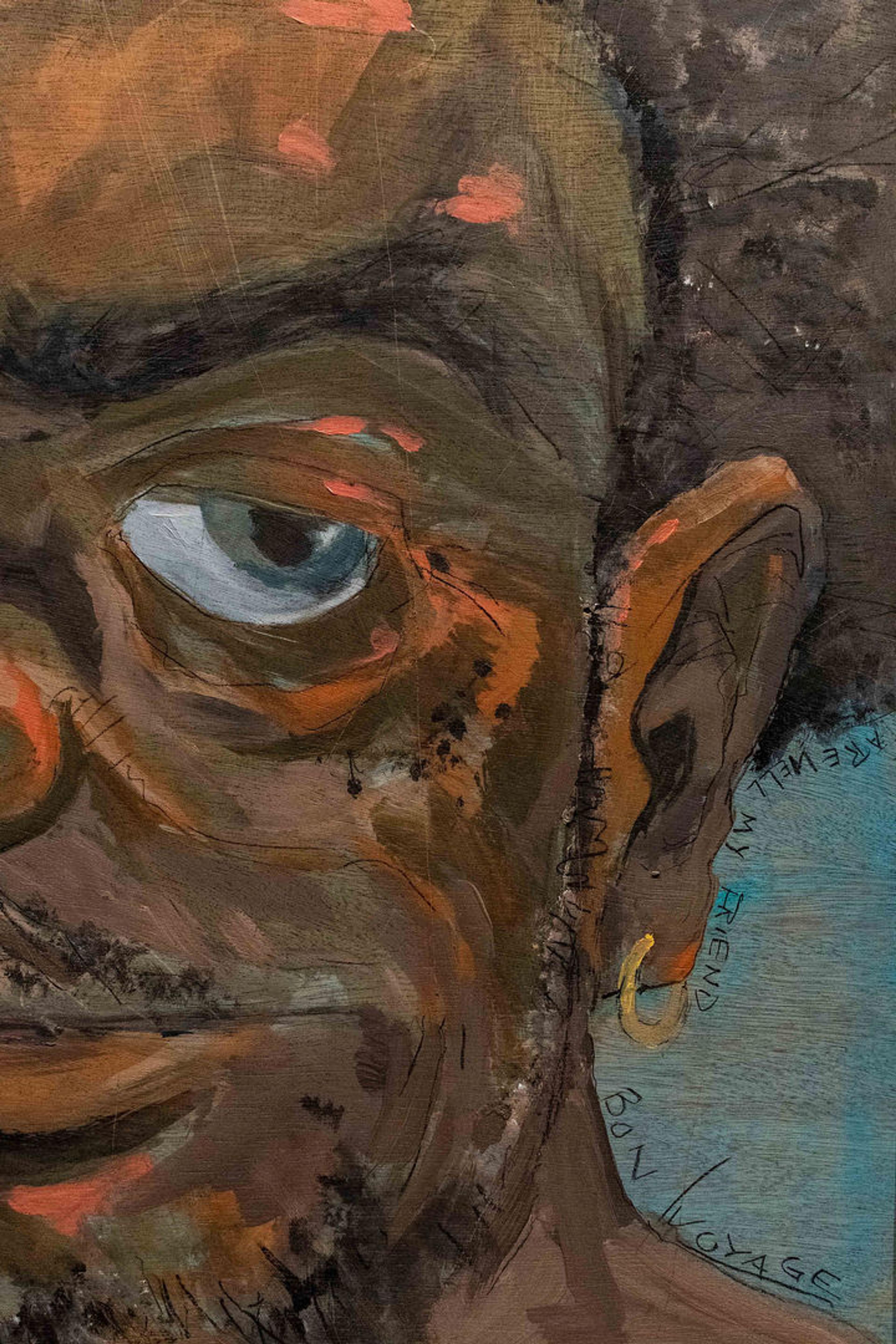

Detail of Charles Was A Good Man / Bon Voyage. Photo by Aurola Wedman Alfaro

Having work in a Met exhibition is incredibly meaningful to me, not just because of the global importance of the institution, but also because of the immense personal connection I feel to the Museum and its collection. I’ve worked at The Met for sixteen years, but prior to that I was a frequent visitor, and loved to wander through the galleries almost randomly, completely immersing myself in the wide variety of cultures and disciplines we have on display. The fact that I was able to contribute a painting to this show that also memorializes a treasured former colleague, friend, and neighbor adds an extra level of significance as well. The experience is bittersweet, but I’m proud that through my contribution I can help others reflect on the memory of Charles.

– Juan Stacey, Supervising Departmental Technician, European Sculpture and Decorative Arts

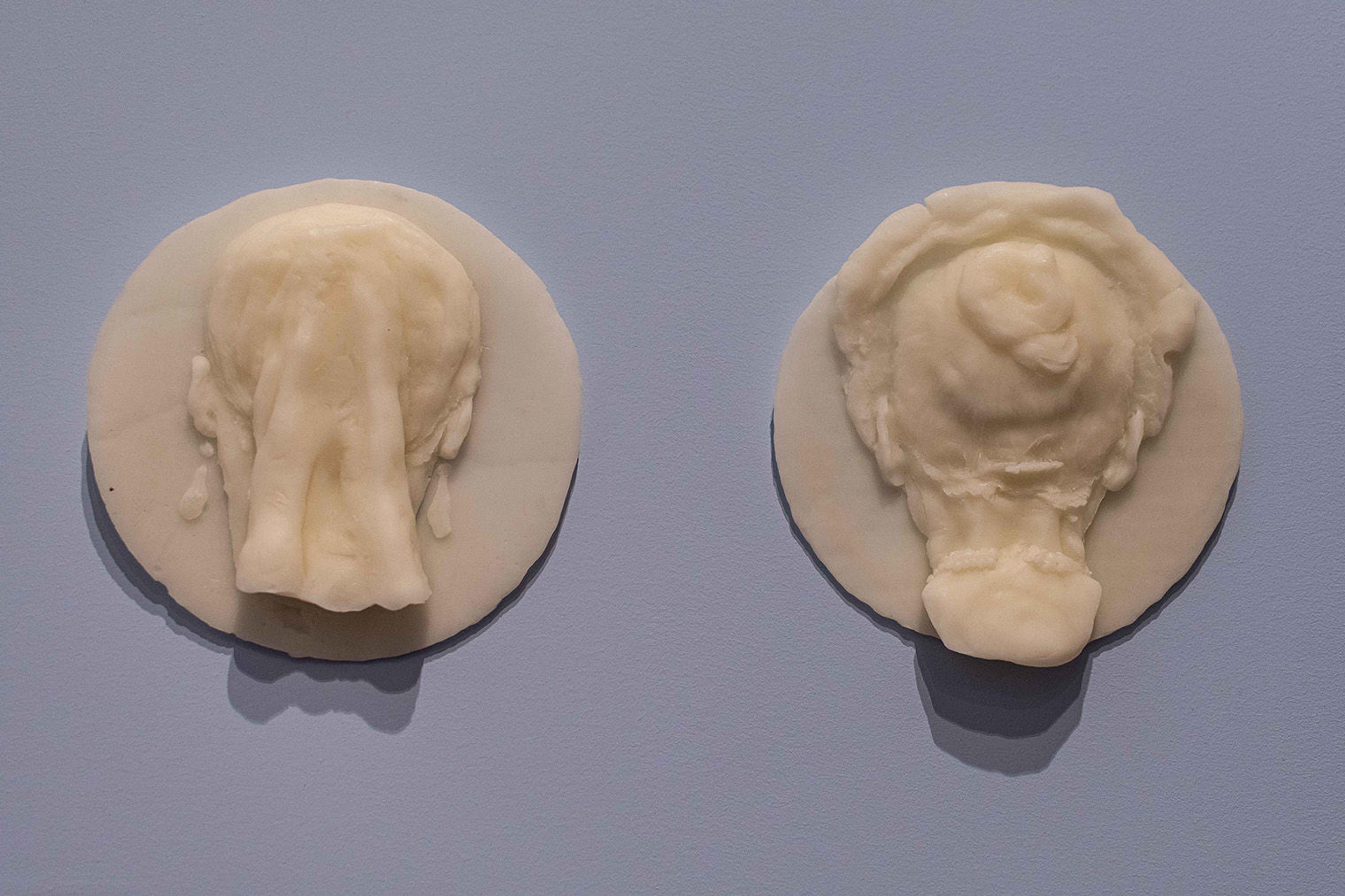

Imani Roach, On Mourning (After Aretha, January 31, 1972); (After Mahalia, April 9, 1968) (2020)

Imani Roach. On Mourning (After Aretha, January 31, 1972); (After Mahalia, April 9, 1968), 2020. Photo by Aurola Wedman Alfaro

The work is about traditions of grieving and the relationship between public/collective and private/individual expressions of grief. It was inspired by and modeled after several historically significant renditions of Thomas Dorsey's 1932 gospel song, "Take My Hand, Precious Lord." Perhaps most associated with Mahalia Jackson, who recorded it in 1956 and performed it on numerous occasions including at Martin Luther King Jr.'s funeral, the song was also sung in tribute to Jackson at her own funeral by her friend and protégé, Aretha Franklin.

I work in cast wax because it is an inexpensive, symbolically rich medium that lends itself well to iteration. I started making sculpture to explore ideas around loss and the body, so the semi-opaque, ghostly quality of wax really appealed to me, as did its association with devotional practices and its ephemerality. I've always made art in my home, where storage space is at a premium, and I like that I don't have to be precious about wax—I can easily melt and recast it—from one piece to another.

– Imani Roach, Assistant Curator Arts of Africa, The Michael C. Rockefeller Wing

Scott Do Santos, Piccolo Bass (2022)

Scott Do Santos. Piccolo Bass, 2022. Photos by Aurola Wedman Alfaro

My piece was an attempt at a short-scale, four-stringed instrument that would be tuned like a full-scale bass guitar. I’ve made full-scale instruments in the past but I wanted to make something small and precious, almost like a jewelry piece but still a functioning instrument. This piece is about practice.

I work in metal because of its resilience and permanence. I’ve worked as a metal fabricator for eighteen years and music has always been a part of my life. Combining the two disciplines allowed me to use the skills I’ve attained in my work life to build something not only visually unique but also with a timbre specific to the materials. Aluminum resonates at different frequencies than wood and its tensile strength allowed me to make a neck with a very thin profile. The process is not that far removed from traditional lutherie in that everything is made by hand. The neck is shaped from a single aluminum flat bar and the body is sheet metal that I form with various hand tools.

I’ve been coming to The Met since I was a kid on school trips and for art history assignments, so to see my work hanging here, and to have heard nothing but kind words about it from coworkers, is great inspiration. Seeing my work in an exhibition at The Met will be, to me, a lasting achievement and will make my parents proud.

– Scott Do Santos, Maintainer, Machine Shop

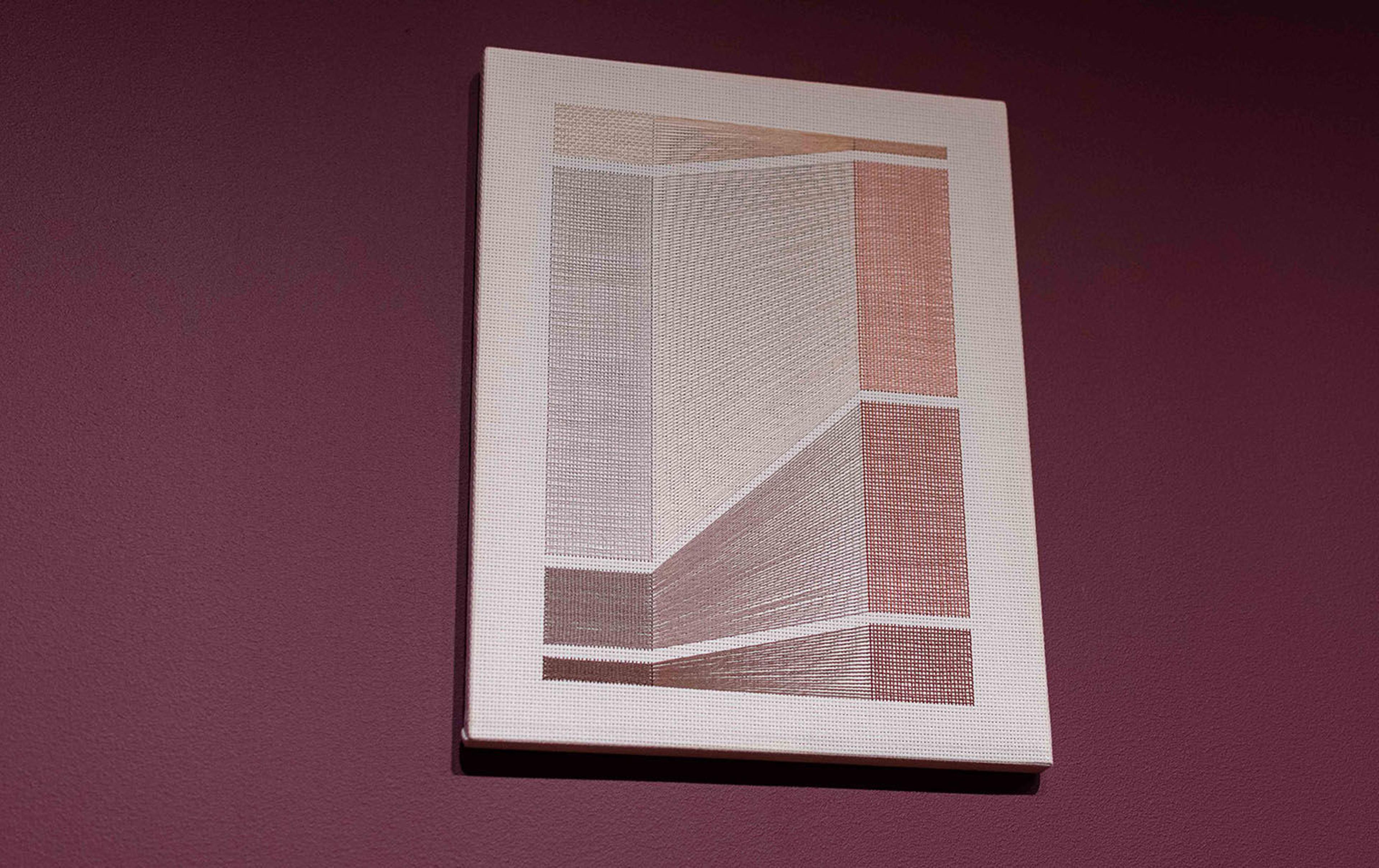

Sarah Parke and Mark Barrow, GRB4 (2014)

Sarah Parke and Mark Barrow. GRB4, 2014. Photos by Aurola Wedman Alfaro

The work draws a correlation between weaving and digital color space, which are both based on Cartesian systems. The hand-woven fabric consists of red, green, and blue threads, like pixels in a screen. To make the composition, different ratios of those three colors are covered in black paint using a brush the same size as a single thread. The piece is titled based on those three primary colors in order of their predominance in the piece.

My background is in weaving and Mark's is in painting. The evolution of our collaboration has been a way for each of us to learn about the other's respective background. And a way to spend time together as partners in art and life. We are grateful any time there is an opportunity to share our work. We often find inspiration in The Met’s extensive collection, so it is both fitting and an honor to have something up at the Museum.

– Sarah Parke, Senior Production Artist, Design, with her partner, artist Mark Barrow

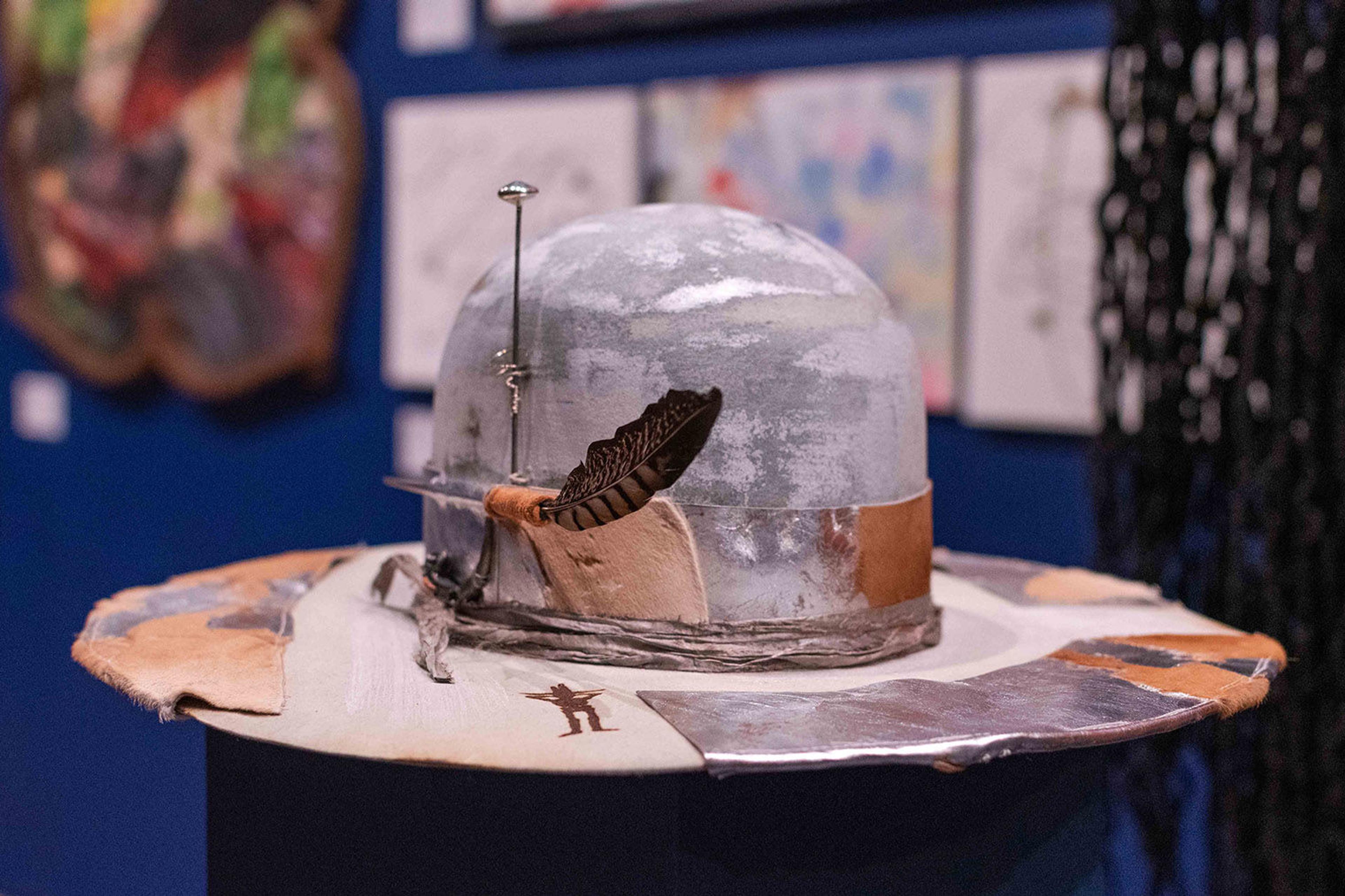

Stan Gamel, Silver Prospector Hat (2022)

Stan Gamel. Silver Prospector Hat, 2022. Photo by Aurola Wedman Alfaro

Silver Prospector Hat was inspired by my father, Spaghetti Westerns, and growing up in the West. It’s a hat I wish I could have made my father when I was at a young age.

My art comes from lessons learned early in life. Throughout my childhood in the desert of Joshua Tree, California, hats protected me from the unforgiving sun and kept me warm on star-watching nights; they were integral to my life, a constant on my childhood adventures. My father was a geologist, and I often accompanied him on his hikes through the desert. I made him rough sorts of hats to protect him from the sun. On these geological expeditions, while endeavoring to strike gold, I discovered something more precious—my creative calling.

Detail of Silver Prospector Hat. Photo by Aurola Wedman Alfaro

I understood from an early age that my true passion was for the arts. My grandmother taught me to paint at a young age, and at fourteen I bought my first camera. I pursued a BA in photography and have worked as a photographer for most of my adult life and began sculpture and jewelry making later in my career. When I discovered the art of millinery, it connected me to my childhood and sparked a creative curiosity in me that I felt obliged to follow. I quickly took millinery classes at the Fashion Institute of Technology and founded my own hat-making studio in New York’s East Village.

– Stan Gamel, Senior Security Officer, Security Management

Ziba Khalili, Touba (2010)

Ziba Khalili. Touba, 2010. Photo by Aurola Wedman Alfaro

Touba is a Sufi mystic tale from Iran, where I was born. I heard it as a child in Tehran and it recounts the story of a young woman who chose to take root and grow old as a tree by planting herself. Touba grew to be the tallest eternal tree in heaven with the longest shadow, protecting infants who die young. I left Iran for Paris and then New York, but I have remained connected to the tale, as an allegory of my own journey and inner peace.

I usually work in clay/terra-cotta or plasteline, and then cast in bronze, which is a long-lasting medium. In this case the base is made of a very strong wood trunk, which was almost impossible to cut out, symbolizing an old root.

To be vulnerable, having my work at The Met, one of my favorite places in the world, where I go to uplift myself by admiring the work of the masters again and again, is a very humbling and intimidating experience. The impact on me and my art-making has been to better understand the role and outcomes of inclusivity in art.

– Ziba Khalili, Volunteer, Visitor Experience

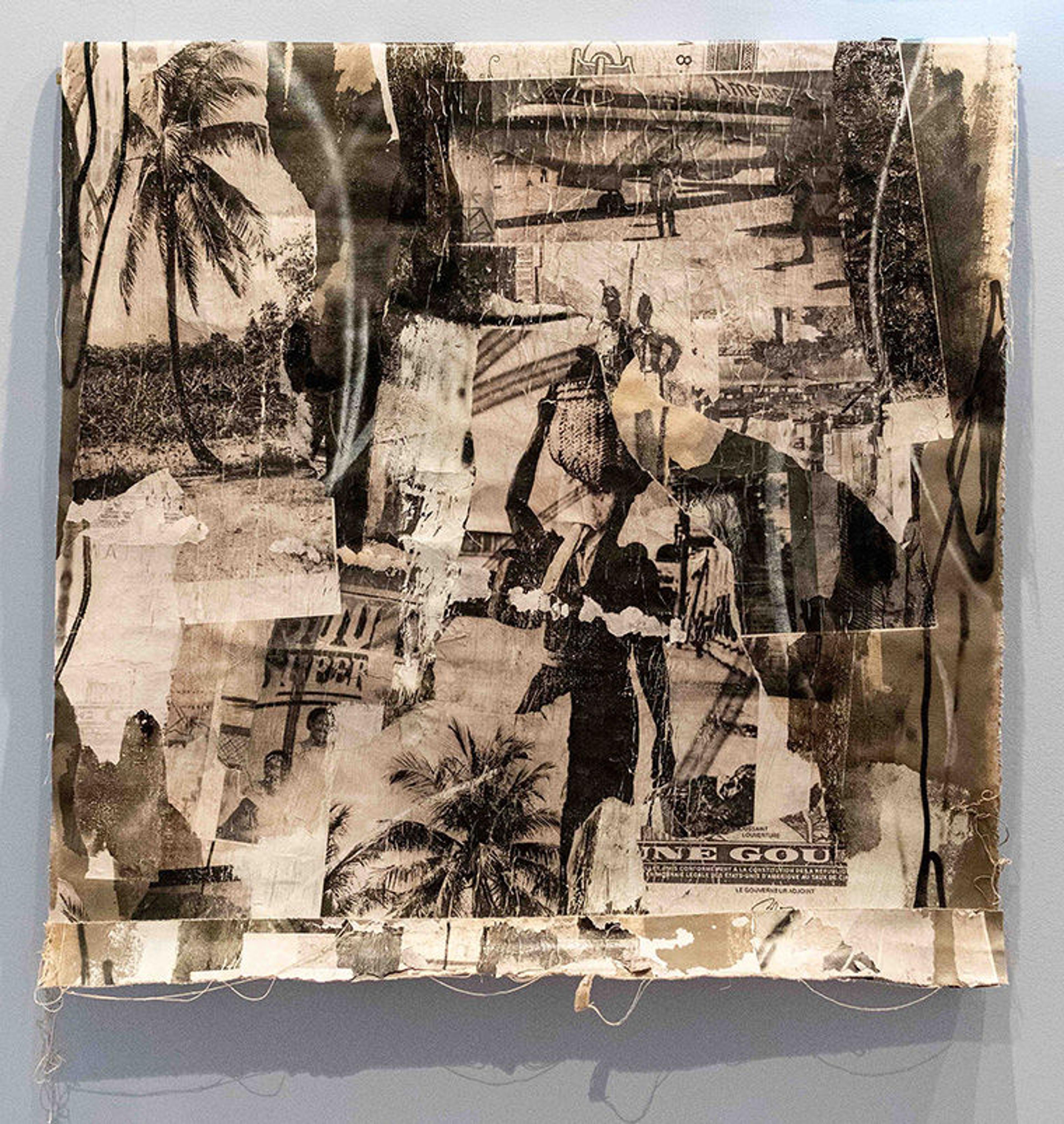

Lionel Carre, Story #7 (2021)

Lionel Carre. Story #7, 2021. Photo by Aurola Wedman Alfaro

Story #7 was inspired by my visits to Haiti in the ’80s as a child. When visiting my family, I recall scenes and situations that were unfamiliar to me as a kid growing up in New York. This piece is about understanding my personal experiences and how they are connected to world history and politics. This piece is my attempt at presenting a glimpse of what I remember from visiting Haiti, what I now understand about the country’s history, and how my past experiences have affected so much of my life, including my visual language.

I work in paper/paint/digital images because this has become a natural progression in my studio practice after years of experimenting with mediums and different surfaces. I have been a practitioner of graffiti art, collage, drawing, and digital photography at different periods. In my recent works I use all these practices to get my message out.

Detail of Story #7. Photo by Aurola Wedman Alfaro

To show my work at an exhibition at The Met is a privilege, an inspiration to keep creating work that speaks on my personal experiences. The feedback I have received has been extremely meaningful.

– Lionel Carre, Supervising Departmental Technician, Modern and Contemporary Art

Drew Anderson, Head Trip (2019)

Drew Anderson. Head Trip, 2019. Photo by Aurola Wedman Alfaro

This piece is based loosely around a short story “White Nights” by Fyodor Dostoevsky in which the narrator walks city streets at night. My work, although very much of New York, is influenced by my growing up in Glasgow, Scotland. Then it was a dark, gray, foreboding, and aging Victorian city. In my youth, heavy industry was at an end, leaving empty, dead, lonely, old buildings, run-down towns and unemployment. I work from sketches and drawings of various parts of New York City to create an atmosphere that is familiar to me. Of course, there are many artists who influence me, Albert Pinkham Ryder and Georges Rouault to name but two.

I work with acrylics, oil washes, gum arabic on paper or wood. Having a full-time job, I don’t have much time to devote to painting so I have learned to work very quickly using these materials. I don’t show work very often so I enjoy having this opportunity at The Met. I think it brings us all a little closer at the Museum; we can discuss each other’s work and receive some feedback. I certainly always feel renewed enthusiasm after the employee show.

– Drew Anderson, Conservator, Objects Conservation

Maria Yoon, Maria the Korean Bride: 50 Weddings / 50 Husbands (2002–2011); Maria the Korean Bride (2013)

Maria Yoon. Maria the Korean Bride: 50 Weddings / 50 Husbands, performance, 2002–2011; Maria the Korean Bride, documentary, 2013. Photo by Aurola Wedman Alfaro

Like many single women of a certain age, I felt a growing pressure to wed. So I took marriage to the next level. I became Maria the Korean Bride, a woman who got married in all fifty states. I took this challenge to explore the institution of marriage and how it is viewed in other cultures. I quickly learned to coordinate on-the-go weddings with volunteer participants who are actual reverends, photographers, and bachelors across the country. My fiftieth wedding was in Times Square, New York City. It took me nine years to finish this project, from 2002 to 2011. The documentary was completed in 2013. It's available on Amazon Prime Video.

I am a performance artist at heart. When I started to get married—the first time was in Las Vegas, NV, in 2002—most people were confused. Bottom line, I wanted to make it easy for them. So I decided to make a documentary and hear what others had to say about marriage and love in America. Keep in mind I never went to film school.

I have been with The Met since I was a high school intern and have always considered The Met my second home. It's the people that I work with and see often who make The Met home for me. Just like my family in all fifty states! Yes, I continue to stay in touch over the years. Now, my entire family can see and support my mission and project.

– Maria Yoon, Teaching Artist, Education

Francheska Santiago, My journey (2022)

Francheska Santiago. My journey, 2022. Photo provided by the artist

My journey is inspired by my son Gabriel, a journey to motherhood, a journey that would seem easy but it's not. I tried to conceive for eight years. We don't all receive things in our time, it’s like traveling on a train ride. We must wait until it gets to our station. In the process of waiting, I learned about patience, perseverance, and achievements because everything has a time. In that train called life, some people will be by us, and others will get off. We will wave until it gets to our destination. I am grateful to God for the opportunity to see my child’s journey. My destination, always, is his happiness.

– Francheska Santiago, Sales Specialist, Retail

Sarah Wambold, Mothers Are Three Times More Likely to be Responsible for Most of the Household Labor (2021)

Sarah Wambold. Mothers Are Three Times More Likely to be Responsible for Most of the Household Labor, 2021. Photo by Aurola Wedman Alfaro

Mothers Are Three Times More Likely to be Responsible for Most of the Household Labor (2021) is based on a data visualization from McKinsey & Company and LeanIn.org’s “Women in the Workplace” study. The 2020 report focused on how the pandemic affected women, and this visualization is about the distribution of domestic labor for heterosexual parents in dual-career couples. The columns represent how fathers (left) and mothers (right) responded to questions about who is responsible for most, all, or equal shares of the household labor. The study concluded: “More than 70 percent of fathers think they are splitting household labor equally with their partner during Covid-19, but only 44 percent of mothers say the same.”

During the first two years of the pandemic, I saw story after story about how the pandemic was disproportionately affecting women. As a mother of two children, whose schools shut down during that time, this was my lived experience as well. As impossible as the scenario felt to me, as someone with a lot of privilege—white, middle-class, “white-collar” job which could be worked remotely—I knew it was far worse for so many more. The clean lines of aggregated, distilled data became a site for both relief and for action. Embroidery, with its legacy of gender bias and privilege, lends both conceptual and literal depth to the work.

I’m embarrassed to say that this is the first artwork I’ve made. It took me three separate attempts to figure out how to work in this format, and I spent a full year doing and redoing my work. To that end, the durational quality and the monotonous labor of stitching—however meditative—are important to the work, as well. When I look at the work I also see the communities of people whose contributions to my life made it possible, from the women in my family who taught me how to stitch, to the math and design professors who guided my thinking throughout my education, to The Met for doing its best to rise to the challenges of the moment, and most of all to my husband, who takes on most of our household labor so that I can pursue my career while we raise our children. I feel profound gratitude and incredibly honored to be able to show the work at The Met.

– Sarah Wambold, Executive Producer, Digital

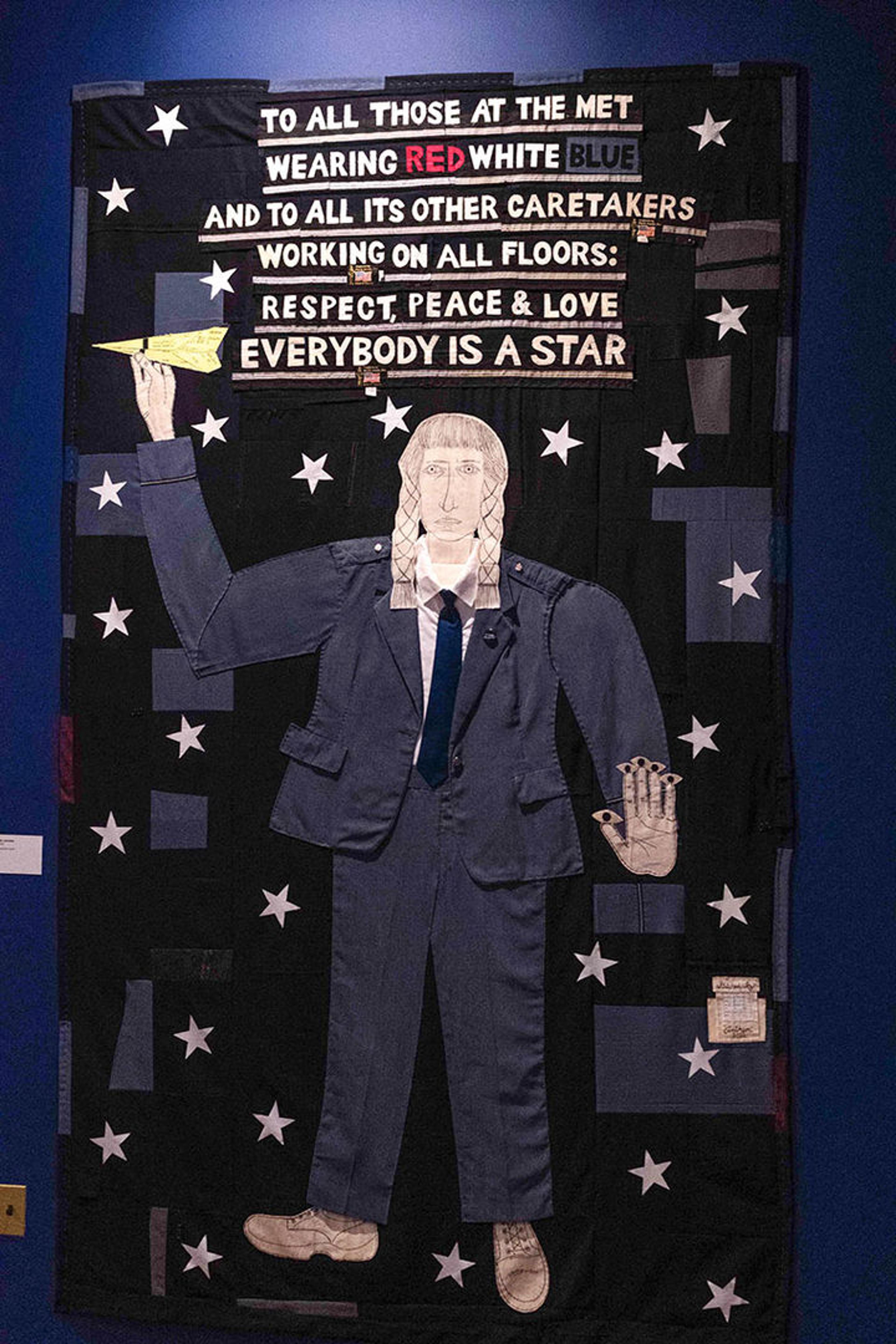

Emilie Lemakis, Anthem (2022)

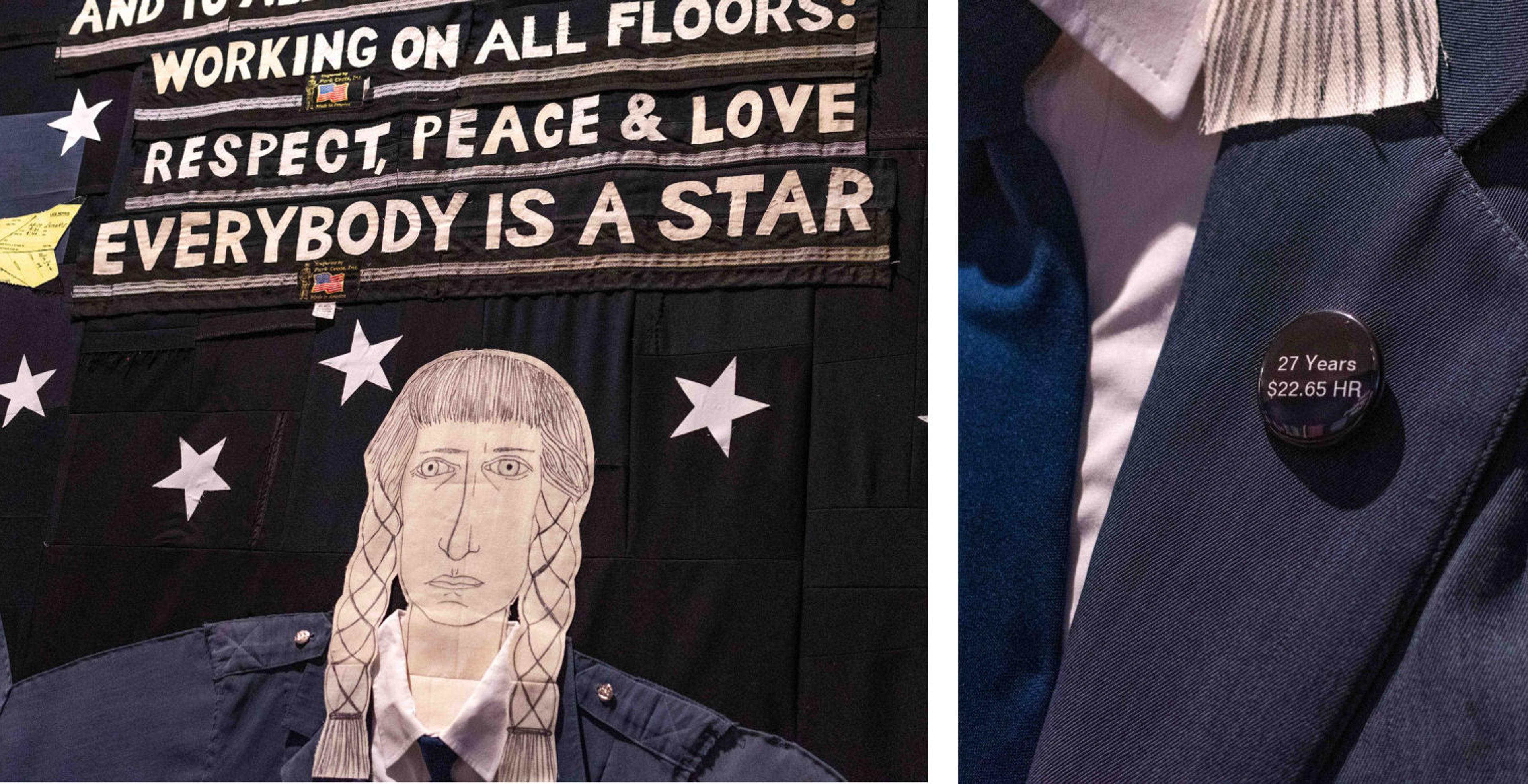

Emilie Lemakis. Anthem, 2022. Photo by Aurola Wedman Alfaro

Anthem is a self-portrait I created to celebrate my twenty-seven years of working as a security guard at The Met and is dedicated to all the people I work alongside in the Security Department as well as all the other departments in the Museum. It is made completely from recycled Met security guard uniforms except for the yellow airplane. The face, hands, shoes, and text were all made from uniform pockets. The text, at the top of the piece, was sewn onto the insides of uniform pants waistbands. The twenty-seven stars, representing the number of years I’ve worked at the Museum, were cut from the white shirts all guards wear as part of their standard apparel. My piece also references a work I’d made for a previous employee art show in 2014—inspired by my struggles with getting to work on time—a giant four-by-eight-foot paper airplane pieced together from more than three hundred (not all my own) small slips of yellow paper called “Late Notices” that security staff receive when they’re late to work. As an accompaniment to the sculpture, I also had late slips printed onto fabric to create a late-slip dress that I wore to the 2014 show’s opening; the much smaller airplane I’m holding in Anthem was made from leftover fabric from the 2014 dress.

Detail of Anthem. Photos by Aurola Wedman Alfaro

The light blue uniform I’m wearing in Anthem is the style of uniform I wore when I was first hired by The Met in 1995. In 2002, our uniforms were redesigned, although the same company, Park Coats—a few of whose labels are incorporated into the work—remained as our supplier. The button that I’m wearing in the piece is from a recent project I led, titled “Met Campaign For Wage Transparency,” which reveals the total number of years I’ve worked at the Met alongside my current hourly rate. Anthem is also about the Museum's many special exhibitions and its wonderful, vast permanent collection I’ve spent so many years getting to know and fall in love with. Early American portrait paintings in the permanent collection were inspirational influences in the creation of Anthem, as were the self-taught contemporary African American quilters from Gee's Bend, Alabama featured in The Met's 2018 exhibition, History Refused to Die: Highlights from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation Gift.

– Emilie Lemakis, Senior Security Officer, Security Management

Installation shots of Art Work: Artists Working at The Met by Eileen Travell

The exhibition Art Work: Artists Working at The Met ran from June 6 through June 19, 2022.