Over the last century alone, successive waves of migration from the Sahel have defined an influential and multigenerational global diaspora. This international presence comprises a significant part of the more than 170 million members who make up what the African Union refers to as Africa's sixth region: those who live outside its continental subdivisions of North, South, East, West, and Central Africa.

Until the 2020 Coronavirus pandemic, a certain freedom of movement allowed many members of the Sahelian diaspora to participate in the socioeconomic life of Dakar and Bamako, as well as Paris, New York, Milan, and beyond. In Something Torn and New: An African Renaissance (2009), Ngugi Wa Thiong'o, one of the continent's most eminent literary voices, reflects on the legacy of this global geography and the process of reconnection or "re-membering" by championing the richness of its many distinct regionally developed expressive languages.

The Sahel has been a defining point of reference for civil-society leaders whose achievements resonate both in the region and across the diaspora, whether as public intellectuals in universities, creative artists performing on a world stage, entrepreneurs developing innovative commercial networks, or advocates for social reform.

Ousmane Sonko was the youngest candidate to run in Senegal's 2019 presidential race, on a platform to end corruption, tax evasion, and eradication of the local currency's ties to the French economy. Imam Mahmoud Dinko founded Coordination des Mouvements, Associations, et Sympathisants, a religious political movement that had called for Mali's President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta's resignation and a new form of governance. Only last month, the Keïta government was toppled by a military coup. Fatou "Toufah" Jallow testified against former President Yahya Jammah at Gambia's Truth and Reconciliation and Reparations Commission, sparking a #MeToo movement and a foundation to support survivors of sexual assault. Sufi scholars Mariana and Ruqayya Niassehave carried on the legacy of their father, the late Tijaniya Sheikh Ibrahim Niasse, in advocating for the rights of women and the education of African youth across the diaspora. And Mati Diop directed the Cannes Award–winning film Atlantics, which addresses issues of migration faced by the region's youth, filmed on location in Wolof. These are only a few who have recently been in the public eye.

Left: Fatou "Toufah" Jallow started a #MeToo movement and a foundation to support survivors of sexual assault in Gambia. Photo courtesy Human Rights Watch. Right: Filmmaker Mati Diop directed the Cannes Award–winning film Atlantics.

Over the last year, Americans have awakened to the extent that US and African histories are inextricably intertwined. This process of reconnection was powerfully launched with the four-hundredth anniversary of the arrival of the first enslaved Africans in Jamestown settlement, addressed by initiatives like Nikole Hannah-Jones's 1619 Project, published by the New York Times. Columbia University professor Mamadou Diouf notes that Jones's project builds on the work of nineteenth-century public intellectuals such as W. E. B. DuBois to reimagine the Black historical narrative and its active presence in contemporary society. It has brought into sharper focus what was previously a highly generalized awareness of that legacy on this side of the Atlantic.

Africa's many-layered past before colonialism, however, remains relatively faceless. As a result, Africa's past appears dehumanized to the West, where figurative depictions are privileged as a primary form of cultural representation. Lack of awareness of key individuals has rendered abstract events that unfolded in a region conceived of as remote. Drawing upon its visual culture and rigorously grounding it into the past may bring the Sahel's millennia-old development more vividly to life.

Malian Emperor Mansa Musa

The oral traditions of Sahelian praise poetry and written commentaries produced since the ninth century do not lack for names of notable individuals from earlier chapters of African history. Recently, they've been brought to life for those outside the region in historicized fiction as well as documentary films.

In Segu, her trailblazing 1984 novel, Maryse Condé introduces us to life at a prominent Sahelian court through the imagined experiences of one of its nobles, Dousika Traore. We view Segu as the epicenter for developments to its north—from Timbuktu, Hamdullahi, to Marrakesh—along the Atlantic coast, and even in the New World, from Gorée to Brazil, following the lives of extended members of the Traore family. And in his 2017 PBS series, Africa's Great Civilizations, Henry Louis Gates Jr. chronicles the history of Sahelian states through on-location footage of enduring architectural landmarks and landscapes, commentaries by historians, and portraits of historical figures as depicted by contemporary sketch artists. Such initiatives seek to introduce that past to audiences whose imagination has not been shaped by exposure to the vivid rhetorical imagery evoked by the Sahel's rich oral literature.

If there's one larger-than-life historical figure who has occupied the Western imagination, it is Mali's emperor Kanku Musa Keita, also known as Mansa Musa (circa 1280 through circa 1337). Only fifteen years after his 1325 pilgrimage to Mecca (or hajj), Mansa Musa was featured prominently on the most advanced maps produced by Majorcan cartographers. While precious for the insights they provide concerning Western attitudes, these images do not represent a Sahelian vision of powerful leadership. Instead, Mansa Musa's reputation as a figure who commands vast sources of wealth is simply translated into that of a European monarch with a darker complexion—he wears a crown, is seated on a throne, and grasps a gold nugget.

Friday Mosque of Jenne, Mali, 1999–2000. Photograph by James Morris

That overlay of foreign visual language in portraying one of the Sahel's most celebrated historical figures is similarly reflected in historians' use of terminologies such as "kingdom" and "empire" to evoke the distinctive forms of Sahelian governance. Roderick McIntosh's analysis of the traces of settlements that arose at Middle Niger sites, such as Jenne-jeno, found no evidence of centralized state hierarchy. In his 2005 study, Ancient Middle Niger: Urbanism and the Self-Organizing Landscape, McIntosh instead interprets these sites through new customized nomenclatures. In African Dominion: A New History of Empire in Early and Medieval West Africa (2018), Michael Gomez identifies Mansa Musa through the devotional structures he commissioned upon returning from hajj, including the Friday mosque on the outskirts of Gao and Jingerebar, in Timbuktu.

Visualizing the Past through Its Material Culture

The Met's exhibition Sahel: Art and Empires on the Shores of the Saharaassembles a corpus of material culture from the Sahel region. It affords critical counterpoints to Western paradigms of what leadership looks like, such as those reflected in the Mansa Musa portraits produced in Majorca, Spain. Men and women portrayed as commanding warriors, selfless mothers, and devout supplicants in fired clay, cast metal, and carved wood—these are the protagonists invoked by griots and court historians.

Equestrian, 3rd–10th century. Niger, Bura-Asinda-Sikka. Terracotta, 24 7/16 x 20 1/2 x 7 7/8 in. (62 x 52 x 20 cm). Institut de Recherches en Sciences Humaines, Université Abdou Moumouni de Niamey, Niger (BRK 85 AC 5e5)

The imposing terracotta equestrian originally positioned at a Bura burial site, now Niger's national treasure, commemorates an otherwise unrecorded first millennium figure who gazes impassively through narrow eyes inscribed in a head defined by a broad, smooth forehead. Outfitted in bandoliers, he grasps the bridle on his steed's elongated muzzle, exposing a bracelet with menacing spikes on his extended arm. This commanding mounted warrior, along with the many similar representations assembled in a cavalcade coursing through the exhibition, is a manifestation of what historian John Iliffe (2005) has described as an ideal of courage and valor that regional leaders embraced before the adoption of Islam.

Another tribute alludes to rulers otherwise unknown or recorded, including a twelfth-century female titleholder, or malika, whose office was equivalent to that of a king. These epitaphs, positioned at a royal burial site at Gao-Saney, take the form of two-dimensional stelae cut from schist and inscribed in Kufic script.

Left: Commemorative Stela for Queen M.s.r (or M.s.n) Inscribed in Ornamental Kufic, 1119. Mali, Gao or Saney. Schist, 36 1/4 x 17 in. (92.1 x 43.2 cm). Institut Fondamental d’Afrique Noire Cheikh Anta Diop, Dakar, Senegal (IFAN) (SO-50-45). Right: Staff: Seated Male Figure, 16th–17th century. Mali, Dogon or Bozo peoples. Copper alloy, iron, 30 1/2 x W. 4 1/4 x D. 4 in. (77.5 x 10.8 x 10.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Edith Perry Chapman Fund, 1975 (1975.306)

When Sunjata formed the Mali Empire, he established vocations for skilled professionals, charging them to channel the creative force of nyama into endeavors such as blacksmithing. Patronage of an elaborate scepter affiliated one sixteenth-century Mande leader with these legendary beginnings. The bearded figure positioned at the finial wears a crown, narrow at its base. He is seated on a spool-like throne in the posture of a mediator, armed with a knife in a scabbard. He holds iron-pointed spears from which ancient Ghana derived its military superiority.

Statement Fashion

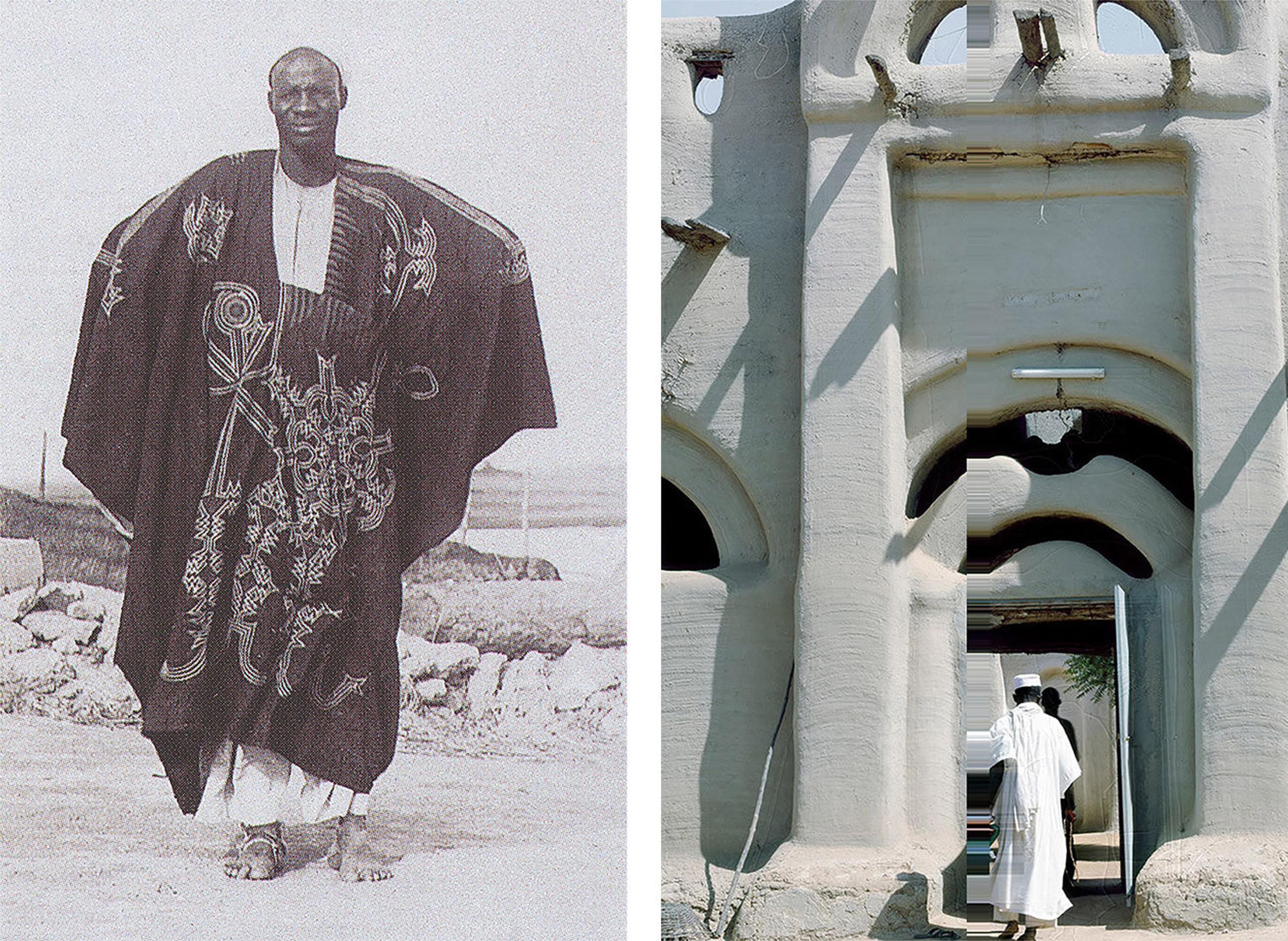

Across the Sahel, the presence and stature of notable persons has been amplified through distinctive genres of fashion. Voluminous embroidered luxury garments and grand boubous afford a sense of the cosmopolitan style and elegance worn by the citizenry of Sahelian cities, such a Timbuktu, Jenne, and Segu.

Left: Earliest photographic record of a lomasa worn by an unidentified man in Jenne, Mali, 1893–94. Photograph by Albert Rousseau. Published in Bernhard Gardi, Le boubou—c'est chic: Les boubous du Mali et d’autres pays de l'Afrique de l'Ouest (Basel, 2002). Right: Jenne, Mali, 1999–2000. Photograph by James Morris

Individuals who placed themselves in physical danger benefited from the protection of an array of highly customized garments invested with spiritual potency that shielded the wearers from physical harm: The fabric canvas of a Bamana Bogolan tunic dyed with mud and vegetal matter was believed to absorb the excess nyama, or energy of action generated when a hunter kills prey in the wild. Worn in battle against the French by a Mande chief, Kinné, a massively heavy armored vest is composed of an arsenal of leather talismanic bands, each filled with Qur'anic passages and camouflaged by a wild outer layer of leather filaments. It is no less important to consider the fate of its wearer, who headed into battle protected by equipment that fell into enemy hands and has since become a relic of colonial conflict.

Leaders of the Bamana states of Segu and Karta are evoked as invincible warriors in carved-wood sculptures of an equestrian warrior charging into battle. Under Segu's founder, Biton Kulibaly, a voluntary youth association, or ton, became a professional martial force, which waged war to exploit neighboring regions. At its height in the late eighteenth century, Segu, led by Da Monzon, controlled the Middle Niger region from Bamako to the Masina Caliphate of Hamdullahi established by the Fulani reformer Seku Amadu. Despite its renown for its powerful military and an alliance forged between its leader, Bina Ali, and its Islamic neighbor, Amadu III of Masina, Segu was conquered in 1861, by the highly charismatic El-Hajj 'Umar Tal.

Installation view of Sahel

Born in Futa Toro in 1795, Tal is identified with a formidable intellect, uncompromising Islamic faith, and brilliant military strategy directed against idolatry. No depictions have come down to us of this larger-than-life crusader, whose actions significantly impacted communities across the Sahel, While many identify him with the relic of a sword currently on display in the Museum of Black Civilizations in Dakar, there has been some debate among Senegalese historians whether the artifact actually belonged to him.

Volumes from the library that 'Umar Tal assembled over the course of his lifetime afford an intimate window into his intellectual and spiritual development. The Umarian Library’s holdings encompass texts by revolutionary Fulani reformists Uthman dan Fodio and Muhammad Bello of the Sokoto caliphate, those acquired during Tal's pilgrimages to Mecca, Tal's own legal and religious arguments for jihad against unbelievers, as well as his succession plan to transfer power to his son Ahmadu Sheku. Expanded in the decades following Tal's death, the library's 518 volumes were removed from Segu to France by Colonel Louis Archinard and are today housed within the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. Tal's descendants have petitioned their transfer to Senegal.

Iconic Figures in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction

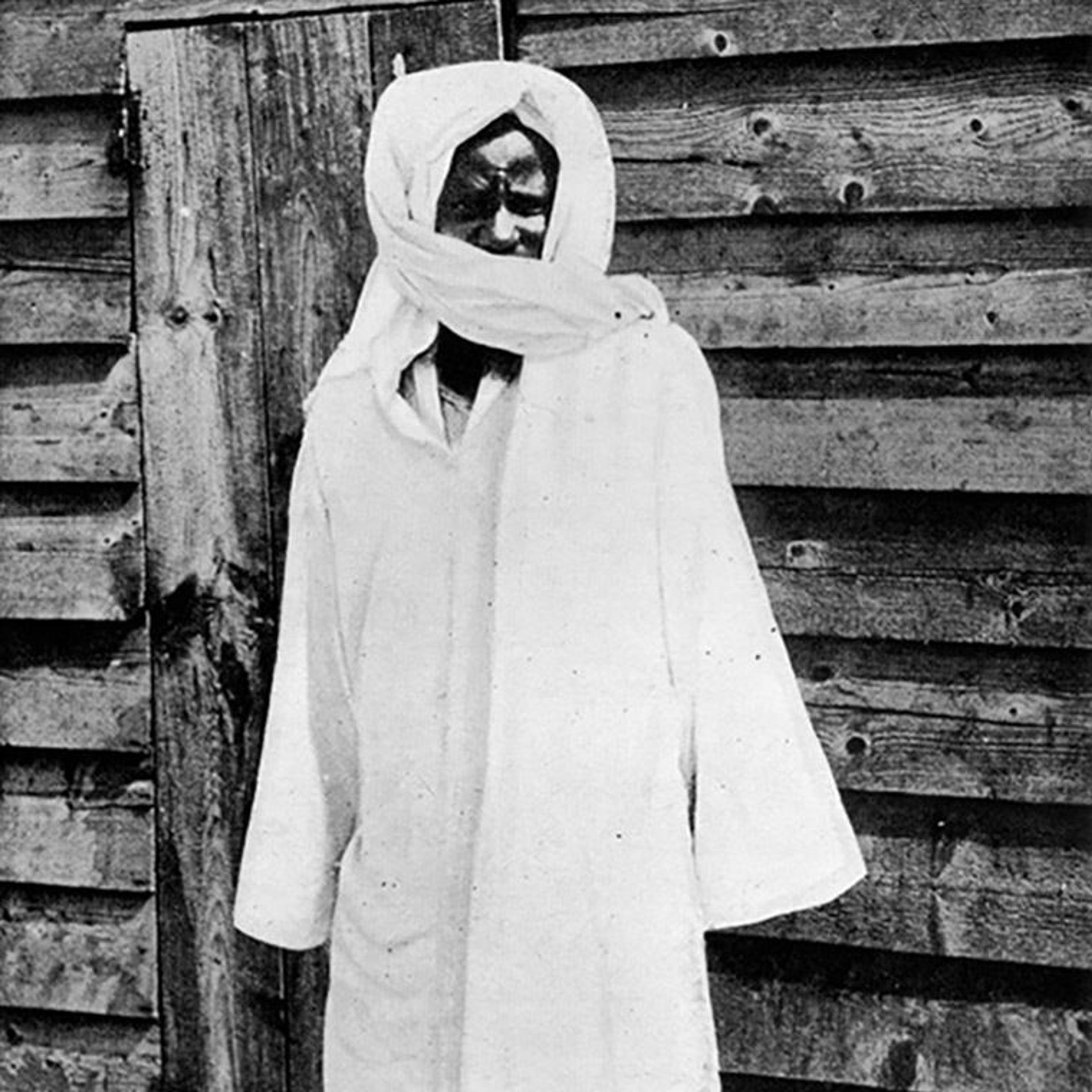

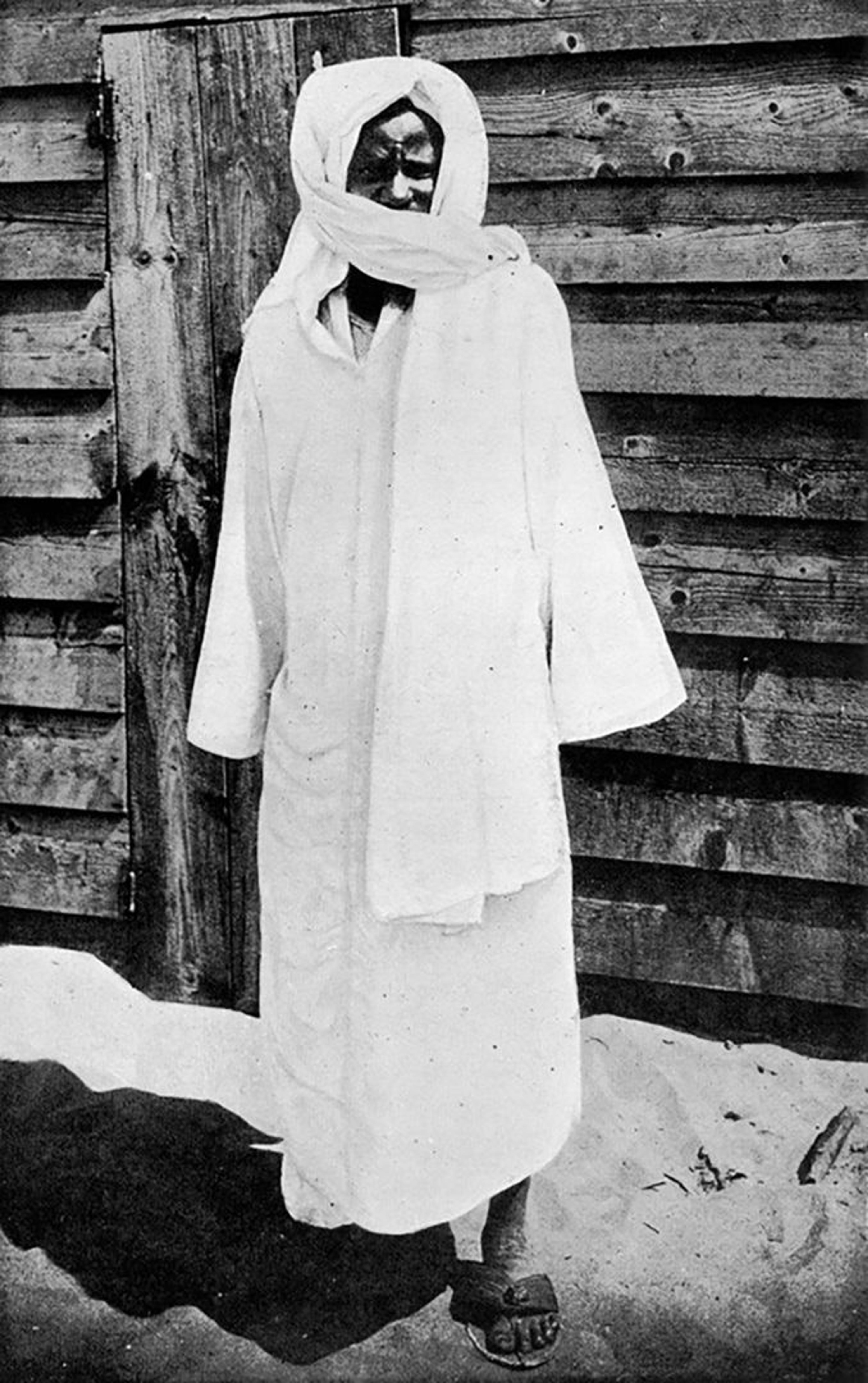

The events narrated in Sahel extend to the eve of French colonialism in 1890. Developments and major societal transformations that unfolded in subsequent decades are evoked in an especially iconic image. In a single 1913 photograph taken in Djourbel, Senegal, Sufi pacifist, poet, and saint Sheikh Amadu Bamba Mbacke (1853 through 1927) stands gazing directly at us. His intense facial expression is all but concealed by the white band of cloth that engulfs his head. With the exception of his partially revealed visage—his furrowed brow, eyes, and nose—his entire bodily presence is engulfed in his flowing white robes. Bamba's white silhouette, against the weathered wooden planks of the mosque behind him, suggest an otherworldly apparition. Beyond his dramatically shadowed face, the only other feature he reveals is his sandaled foot anchoring him to this world.

The only surviving photo of Sheikh Amadu Bamba, taken in Djourbel, Senegal, c. 1913. Public-domain image courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Sheikh Amadu Bamba was born into a family of Muslim holy men, or marabouts, in the eastern Baol village of Mbacké. His writings and teachings advocate for personal piety and reform, a stance of nonviolence over jihad, and the rejection of venal state power. In a much-quoted verse, he admonished, "The warrior in the path of God is not who takes his enemies' life, but the one who combats his nafs to achieve spiritual perfection."

The French colonial regime considered Bamba a dangerous revolutionary. They were threatened by his popularity and sought to diminish his prestige by forcing him into a decade of exile and imprisonment in Gabon and Mauritania. In the face of this persecution, Bamba's commitment to pacifism and piety, as well as his direct communion with God's higher authority, made evident his saintly character and his successful resistance.

While many artists have imaginatively portrayed this venerated individual's acts of piety, the fleeting moment captured by the ghostly photographic impression occurred during five years of house arrest following his return from exile. While no photographic negative is known to have survived, the power of this single image of Bamba's saintly presence, in which his baraka, or blessed energy inheres, has been replicated in the form of photocopies and lithographs, glass paintings and murals. Historian Cheikh MBacke Babou, chronicling this legacy, notes that today, nearly a century after Bamba's death, the global population of his Murid followers is over four million, and the annual pilgrimage to his tomb constitutes one of the largest gatherings in the world.

Over the last century, photographs captured the emergence of leaders of new Sahelian nation states. Official portraits of individuals such as Leopold Sedar Senghor and Modibo Keita came to establish distinct Senegalese and Malian identities both within the Sahel and to the world at large. Rather than be defined by images of themselves taken by others, they actively shaped their own representations, at once as individuals and unifying fathers of their nations.

The authors wish to thank historian Mamadou Diouf, Leitner Family Professor of African Studies and History at Columbia University, for his insights into this subject and editorial review.