Listen to the podcast

This podcast features the celebrated painter Alice Neel speaking about her life, inspiration, and “radical humanism.” Interviews with artists Jordan Casteel and Miguel Luciano, and curator Jasmine Wahi illuminate how Neel’s art, activism, and fight for social justice resonate today.

Alice Neel: People Come First

Learn more about the exhibition Alice Neel: People Come First (2021).

Who Was Alice Neel?

Barbaralee Diamonstein-Spielvogel:

Our guest tonight is the celebrated painter of what she prefers to call “pictures of people.”

Alice Neel:

It’s a privilege, you know, to paint. It takes up a lot of time and it means there’s a lot of things you don’t do.

Narrator:

That’s the voice of artist Alice Neel from an interview conducted in 1978.

Neel:

But still, with me painting was more than a profession. It was also an obsession. I had to paint, you know.

Narrator:

Neel’s life-long commitment to painting, her “obsession” as she called it, resulted in an extraordinary body of work spanning seven decades of the twentieth century.

To accompany The Met’s landmark exhibition Alice Neel: People Come First, we invited contemporary artists, activists, and curators to respond to the artist herself. This series of conversations will give you a sense of who Neel was and why her work still speaks to us today.

And if you’re listening at the Museum, know that this isn’t a guided tour. Feel free to wander around and listen as you take in the exhibition.

Terry Gross:

Welcome to Fresh Air, it’s a pleasure to have you here.

Neel:

Thank you.

Narrator:

Neel sat for a series of interviews at the end of her career, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when Neel herself was in her late seventies. You’ll hear excerpts from these over the course of this podcast.

Neel:

One of the reasons I painted was to catch life as it goes by, right hot off the griddle, because when painting or writing are good it’s taken right out of life itself, to my mind.

One of the reasons I painted was to catch life as it goes by, right hot off the griddle, because when painting or writing are good it’s taken right out of life itself, to my mind. —Alice Neel

Narrator:

For decades in New York City, she created street scenes, landscapes, and still lifes. But she’s best known for what we may generally think of as portraits but that she preferred to call her “pictures of people.”

Neel:

I was born on the 28th of January 1900. Think of the benighted world it was then. I was born at Marion Square, Pennsylvania. But then when I was small, about three months old, we move to a little place called Colwyn, P.A.

I always wanted to be an artist. I always knew. I don’t know how I knew. But I know when I was a child, I’d get a paint book, you know, watercolors or crayons. And that was my best present.

Narrator:

At that time, it was pretty unusual for young women to pursue careers in the arts, or at least the kind of career Neel wanted. But after working her way through night school for a few years …

Neel:

I went to the Philadelphia School of Design, and by the time I got there it was like a school where rich girls went before they got married.

Diamonstein-Spielvogel:

And that’s what you did.

Neel:

Well, but I didn’t do it for that reason. I did it to learn about art. And I worked hard there for four years.

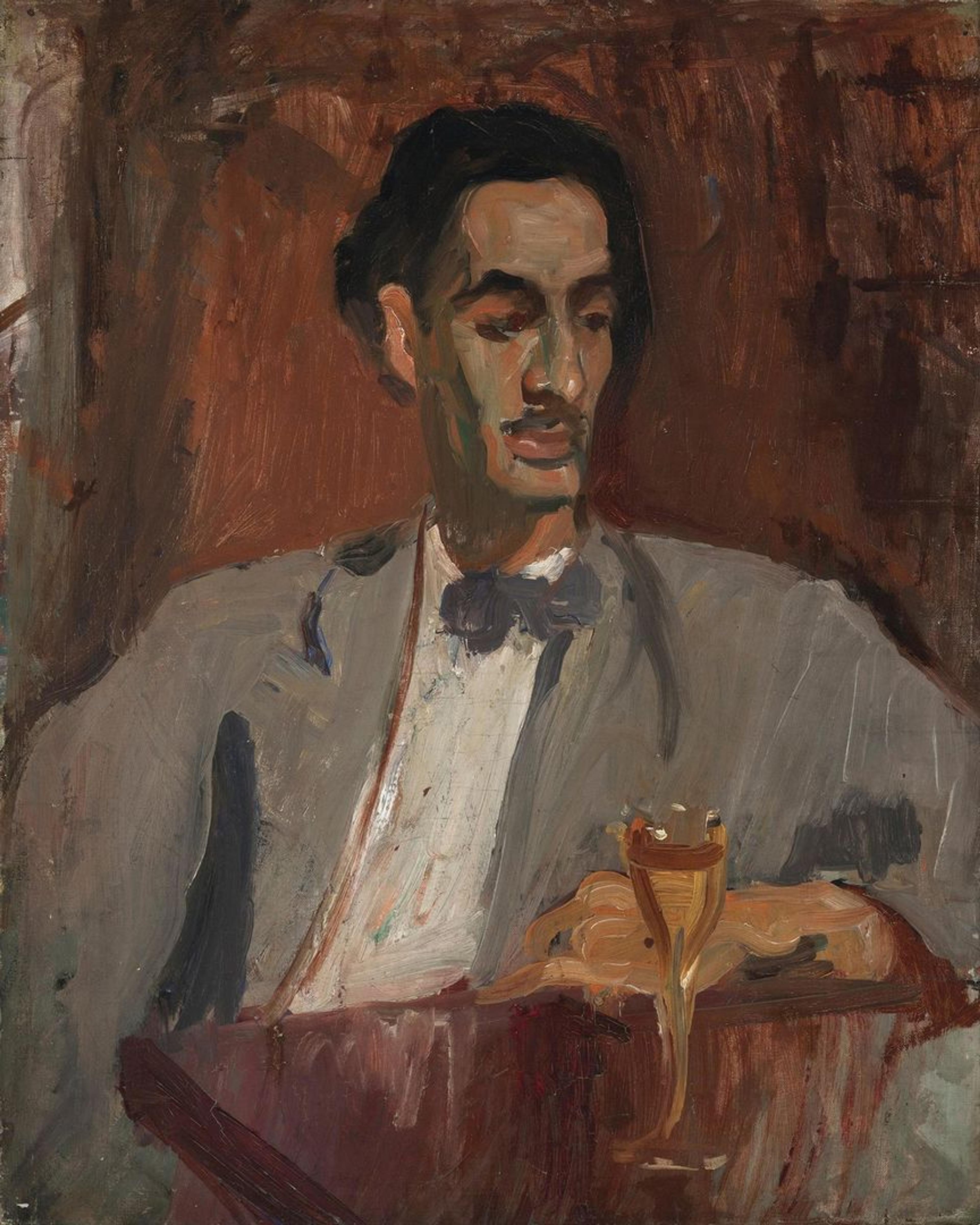

Alice Neel (American, 1900–1984). Carlos Enríquez, 1926. Oil on canvas, 30 ¼ × 24 in. (76.8 × 61 cm). Estate of Alice Neel © The Estate of Alice Neel

Narrator:

During her last year of art school, in 1924, Neel met Carlos Enríquez, a Cuban painter from a wealthy family.

Neel:

I came out of that little town the most repressed virgin that ever lived. I met him in a summer school. Oh, he was gorgeous. Oh, it was very romantic, the whole thing—we got thrown out of the school.

So I married him. I went to Cuba, and then of course, all we did was paint day and night.

Narrator:

Living in Havana, Neel joined a vibrant community of avant-garde Cuban artists, writers, and musicians. The next few years marked dramatic familial upheaval and loss, including the death of a child.

Interviewer:

Did you feel abandoned?

Neel:

I was abandoned. I didn’t feel it—I was. I had a terrible nervous breakdown after the Cuban life broke up.

Narrator:

Neel even attempted suicide. She returned home to Pennsylvania to recover, and there she returned to her painting with renewed commitment and determination.

Neel:

The road that I pursued and the road that I think keeps you an artist was that no matter what happened to me, you still keep on painting. You just should keep on painting no matter how difficult it is. Because this is all part of experience, and the more experience you can have, the better it is. Unless it kills you, and then you know you’ve gone too far [laughter].

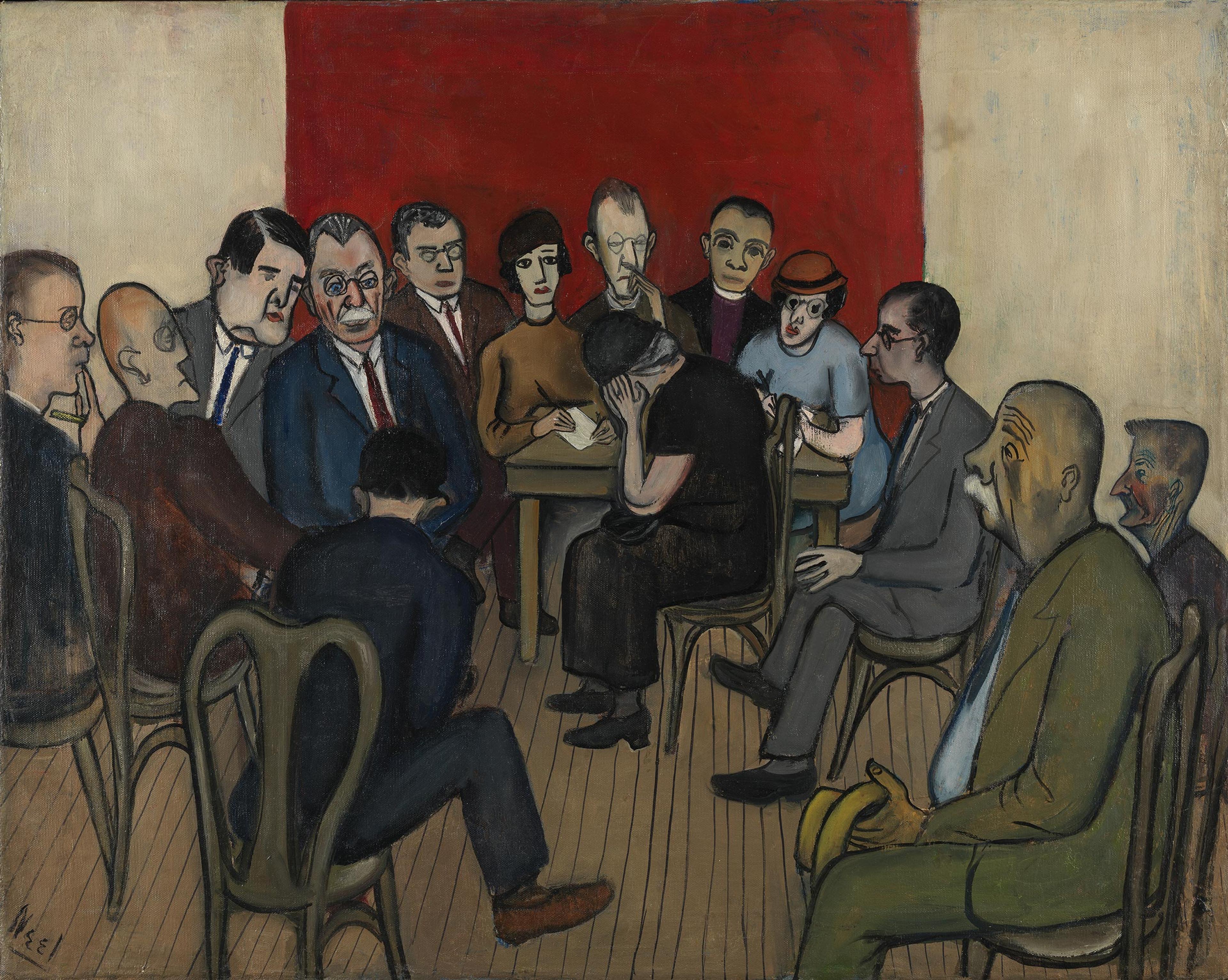

Alice Neel (American, 1900–1984). Investigation of Poverty at the Russell Sage Foundation, 1933. Oil on canvas, 24 ¼ × 30 ¼ in. (61.3 × 76.5 cm). Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Art by Women Collection, Gift of Linda Lee Alter © The Estate of Alice Neel

Narrator:

The United States was now in the middle of the Great Depression. Neel got a job with the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project, a government program that paid artists to make art.

Neel:

To participate in the W.P.A. and to see what was going on around you made you more aware of reality. I had not done street scenes before. But on the W.P.A. I did any number of neighborhoods and street scenes, where besides showing the street and the neighborhood and everything else, I showed the condition of the people in it.

Narrator:

She painted left-wing intellectuals and Communist Party leaders, unflinching female nudes and erotic drawings and watercolors, which were—understatement—radical at the time.

Neel:

I never could show it till ’71. And by the time I showed it everybody was so used to nudity they hardly looked at it.

Narrator:

But as the 1930s ended and the 1940s began, tastes changed and galleries mostly stopped showing or selling her work.

Neel:

You see, all during the forties and fifties New York was nothing but Abstract Expressionists. Nobody painted people or anything like that; it was just Abstract Expressionism. And they wouldn’t let people-painters even get a foot in the door. But during that time, I couldn’t give up what I was interested in for what was the fashion.

Narrator:

What she was interested in never really changed …

Left: Alice Neel (American, 1900–1984). Henry Geldzahler, 1967. Oil on canvas, 50 × 34 in. (127 × 86 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Anonymous Gift, 1981 (1981.407). Image © The Estate of Alice Neel. Right: Alice Neel (American, 1900–1984). Andy Warhol, 1970. Oil and acrylic on linen, 60 × 40 in. (152.4 × 101.6 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, Gift of Timothy Collins. Image © The Estate of Alice Neel

Neel:

I did a lot of people in Spanish Harlem. I painted James Farmer in ’64. He was then marching in Mississippi, I think it was. I did a lot of very sophisticated people. Well, the greatest one was Cindy Nemster, that little art critic. My Henry Geldzahler is now at The Metropolitan thank god. By the way, the painting I did of Andy Warhol—which he told me he considers the definitive painting of him—is in The Whitney Museum …

Narrator:

During the 1960s and ’70s, the art world rediscovered Neel thanks in large part to her own efforts and reaching out to a younger generation of artists, critics, and curators.

Members of the Women’s Movement also played an important role championing her as an irreverent and uncompromising feminist artist.

Alice Neel died in 1984 at the age of 84. But today, the radical humanism and empathy at the heart of her practice feels more relevant than ever.

Jordan Casteel:

Somebody along the way handed me a book of Alice Neel. That book changed everything for me.

Miguel Luciano:

She was painting in a way that reflected the community that she lived in, I think in the best way that she knew how.

Jasmine Wahi:

She made a vested effort in creating a genuine reflection of who those individuals were and tried to show an authentic vision through their eyes of themselves.

Narrator:

During this podcast, you’ll hear much more from Alice Neel, as well as artists Jordan Casteel and Miguel Luciano, and Bronx Museum curator Jasmine Wahi as they explore their relationship to Alice Neel and her work.

Next, what did Neel mean when she said she was a “painter of people?”

Jordan Casteel on Alice Neel’s “Pictures of People”

Barbaralee Diamonstein-Spielvogel:

You’ve described yourself frequently as a “collector of souls.” But I think you’re a collector of bodies too.

Alice Neel:

Well, the soul usually lives somewhere. Unless you believe in disembodied souls up in the clouds. Now there may be a few, but most of the souls we meet are clothed in flesh, aren’t they?

Narrator:

The 2021 exhibition at The Metropolitan Museum of Art is called Alice Neel: People Come First. The title comes from something Neel once said to a left-wing, pro-labor journalist in 1950. “For me, people come first,” she declared. “I have tried to assert the dignity and eternal importance of the human being.”

Diamonstein-Spielvogel:

I guess you’re best known for your soul-bearing exposes. And you say that your greatest strength as a painter is in your psychological acumen. What do you mean when you say that, Alice Neel?

Neel:

Well, if I had been a psychiatrist, I would be wealthy [laughs]. As it is, in the process of painting someone, I reveal not only what shows, but what doesn’t show.

Jordan Casteel:

My name is Jordan Casteel and I am an artist, specifically a painter. I very distinctly recall somebody giving me an Alice Neel book. That book changed everything for me.

Neel:

I take the same attitude toward myself I take to everyone, you know.

Casteel:

I felt that I knew Alice as much as I knew the subjects of her work and the people that she painted. And that came with a fearlessness and a freedom that I saw in her mark making.

Neel:

It isn’t flattering. I mean, you see my flesh falling off.

Casteel:

Like, a wonky hand or the proportion of something could be off, or a finger could be kind of twisted out of the frame. And that felt distinctively human.

And I feel like when I first saw Alice’s work, that was the first time that I thought, “Oh, there’s a place within the context of the art world to be distinctively human, to speak one’s truth on canvas.”

Narrator:

Casteel takes photos of her subjects, and then paints from those. But Neel invited her subjects into her home.

Neel:

So then I talk to them, and then I see how it is, they’re relaxed, and then I just start painting. And I give them as many rests as they have to have, but I can be an awful slave driver if they don’t demand their rests, you know, because I get really involved. And then I really get the spirit of the person—not only their features; it’s more than their features, it’s the sense of them also.

Casteel:

I love hearing, some of the subjects who were painted by her describe the fact that she would just speak constantly. She was just talking, talking, talking, talking, always just talking …

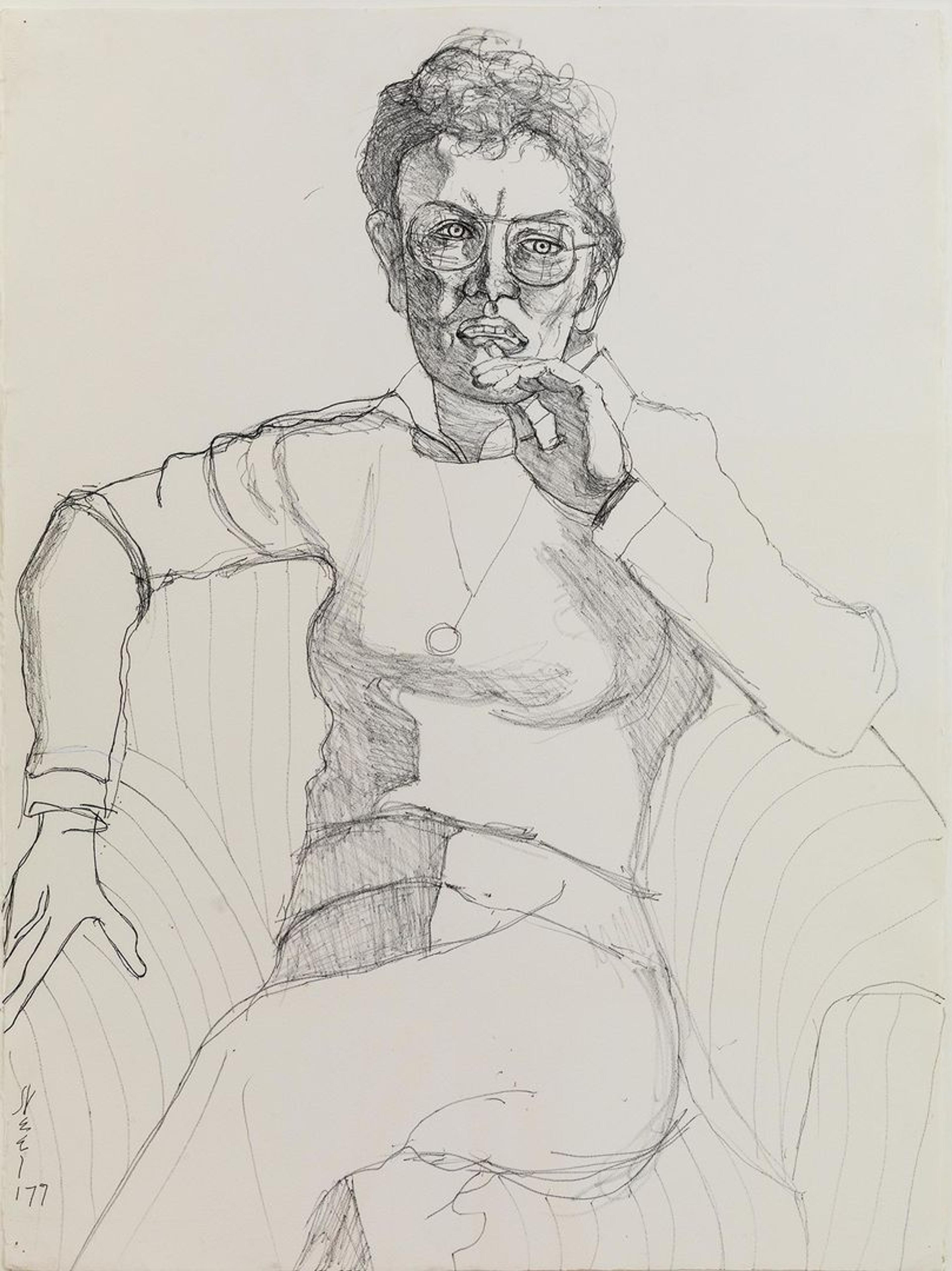

Alice Neel (American, 1900–1984). Mary Garrard, 1977. Graphite on paper, 30 ¼ × 22 ½ in. (76.5 × 57.2 cm). Estate of Alice Neel © The Estate of Alice Neel

Narrator:

Feminist art historian Mary Garrard sat for Neel.

Mary Garrard:

She carried on a constant monologue. It was a kind of soliloquy. She would touch on themes that she kind of knew you were interested in. And she did this to, in some ways to confront her sitter, you know, she would sort of challenge them on things to make them, you know, react to her. She could talk from that part of her mind so that the subconscious would do its work underneath—so that she could paint, you know, from somewhere else.

Narrator:

But beneath the chatter, Neel was incredibly focused on the person she was painting. As she explained in a documentary film …

Neel:

See, I get terribly involved, so that I leave myself, and I go into that person. So sometimes after the person goes, I feel just as though I have an empty inside, that I have nothing inside.

Sometimes I get so—It’s empathy, almost. I get so identified, that when they leave, you know, I feel like an untenanted apartment.

Casteel:

Hearing her speak about the sadness and the kind of hole in her heart after the subjects left, or also feeling so deeply involved with a person while she’s making the painting, and then feeling the real dissonance and the disconnect that happened as they departed … I distinctly remember hearing her say that, because it feels so true for me, too. It is the blessing and curse of my life, my sense of empathy. And that’s what she’s describing.

Narrator:

In 1962, Neel moved to the Upper West Side of Manhattan, near Broadway and 107th St. It was a diverse neighborhood, home to large Black and Latinx communities. As she’d always done, she regularly invited people from the neighborhood to her studio.

Neel:

I look. But different people look in different ways. I really wouldn’t have to know them first or even meet them first. I’d just paint. Just sit in front of a canvas and paint. The pleasure I get is the process of painting itself.

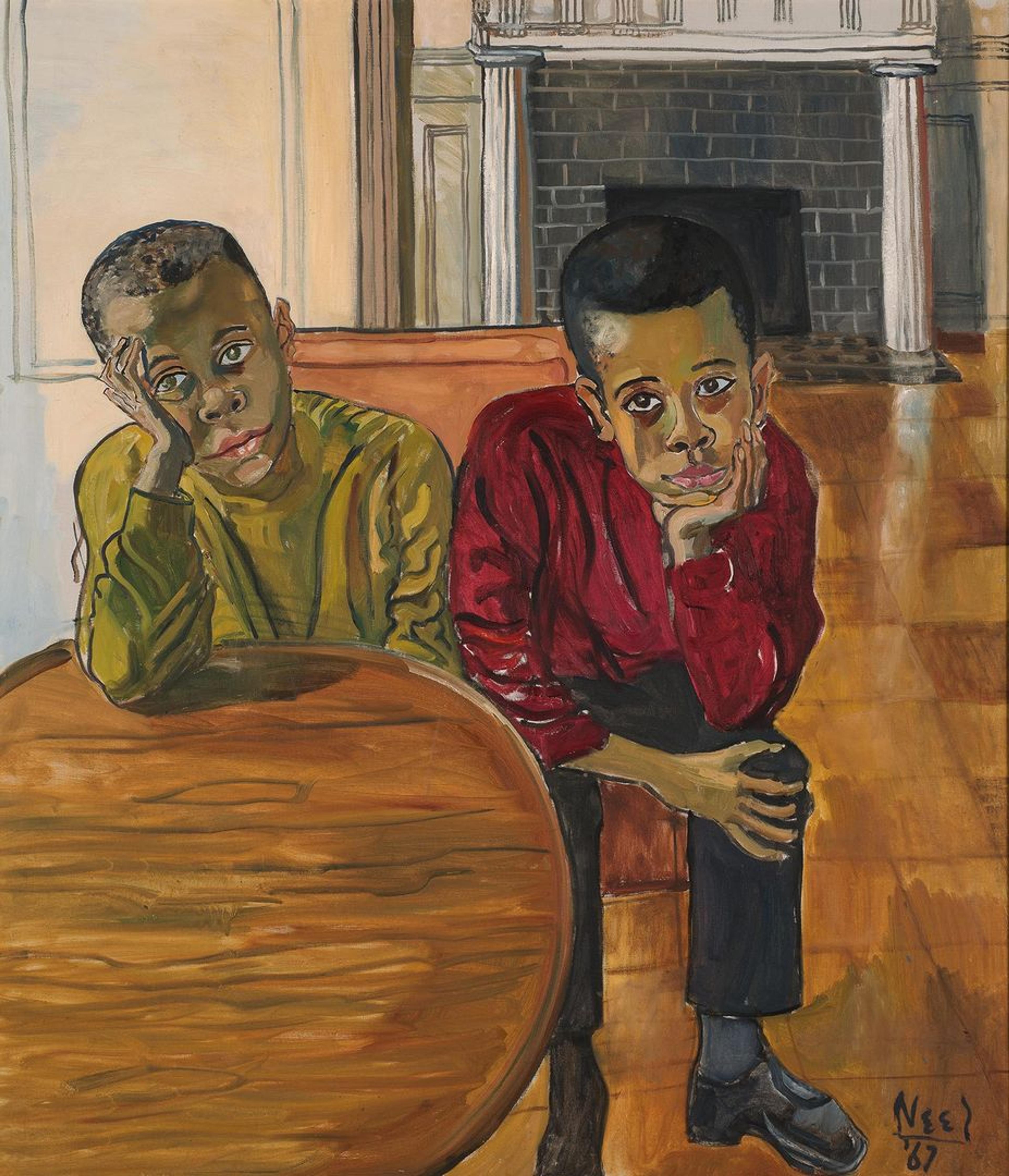

Alice Neel (American, 1900–1984). The Black Boys, 1967. Oil on canvas, 46 ¼ × 40 in. (117.5 × 101.6 cm). Tia Collection, Santa Fe, New Mexico. Image © The Estate of Alice Neel

Narrator:

In 1967, Neel painted The Black Boys. You can find this painting on The Met’s website.

Casteel:

This was one of the paintings that I saw in that first book that I had when I was learning about Alice Neel for the first time.

Narrator:

It still gives Casteel pause.

Casteel:

And I remember seeing these two young Black boys, with their heads in their hands, and they’re leaning forward and into the frame. It almost feels like they’re falling out of the frame and into our life. I felt that their eyes, in that particular portrait, spoke volumes about who these young men dreamed of themselves as being and where they felt that they could go, but also very present in where they are, right here and right now.

Neel:

I like it first to be art. So actually dividing up the canvas is one of the most exciting things for me. And then I like it not only to look like the person but to have their inner character as well. And then I like it to express the zeitgeist. See, I don’t like something in the sixties to look like something in the seventies.

Casteel:

I love the way that they’re kind of looking at her longingly. There’s also this sense that it’s like, “Okay, I’ve been here for a long time, are you done yet?” Like, I could feel a sense of angst, of … to have young boys sitting still for that long period of time, you couldn’t pay my nephews to do that.

Narrator:

Like The Black Boys, Neel gave many of her paintings generic titles.

Casteel:

In no way do the people or the bodies, or really, the lives that she is documenting feel like a voyeuristic stance. They feel like true, authentic relationship-building. That she was tapping into the breadth of the Black experience, and the white experience, and just, again, the human experience; I do see value in our capacity to just see one another as human beings. That’s the bottom line; that we are human beings.

Their eyes … spoke volumes about who these young men dreamed of themselves as being and where they felt that they could go, but also very present in where they are, right here and right now. —Jordan Casteel

Narrator:

When Casteel first got to know Neel’s work …

Casteel:

… I had only known, up until that point, the work of African American artists, primarily. That was the work that was surrounding me, and I am so grateful for that. But I also needed to know that there were people unlike me, who had the capacity to represent me and my body with real generosity and grace. And I feel that respect in her portraits. And that’s all any of us could ask for.

Narrator:

But, boy, did Alice Neel hate the word “portrait.”

Neel:

Actually, portraits are where more crimes are committed than any other form of art. I mean, witness the college professors that hang on walls in petrified form. I think they’re frightful. But I break those rules, and they’re considered bold by timid people. They’re not really bold. They’re just the truth, you know?

Narrator:

In both style and subject matter, Neel’s depictions didn’t have much in common with conventional portraits, which she found stuffy and traditional.

Diamonstein-Spielvogel:

You talked about yourself as a painter of people. In fact, you use before the reference, “people painter.” Why do you object to be to being called a portraitist? And what does that mean to you?

Neel:

Well, I tell you, the only reason is because I’m just like everybody else, I get conditioned. And the portrait was considered such a low form of art for so long, that I was tainted with that.

Casteel:

When I think about her making a distinction between portrait and the painting of people, there are layers to that decision making in my mind. And I think of her decision to be explicit about how she describes the work she was making, was one in which she was acutely aware of the way that society and the people around her would make her “less than” if she fit into a simple box.

And she wanted the ability to say, “This is what my practice is, that these are real people. I am a real person. It is not just painter and subject.”

And that nuance of language, I think, holds great power. There are many ways that we use language to define ourselves, and the ability to define herself for herself, I think, was the most important.

Jasmine Wahi on Alice Neel’s Feminism and Social Justice

Alice Neel:

I believe in feminism. I was born believing in it. My mother used to say, “I don’t know what you expect to do in the world, you’re only a girl.” But if anything that made me more anxious to do something.

Narrator:

As she tells it, even from a young age, Alice Neel was always determined that being a woman would not hold her back. But for Neel, women’s liberation was just one part of a bigger, broader fight: for equality and against injustice.

Jasmine Wahi:

I know that she had many affiliations, but I do think that her most prolific way of expressing her political affiliations was actually through her work.

Narrator:

That’s Jasmine Wahi, the Holly Block Social Justice Curator at the Bronx Museum.

Alice Neel (American, 1900–1984). Self-Portrait, 1980. Oil on canvas, 53 ¼ × 39 ¾ in. (135.3 × 101 cm). National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. Image © The Estate of Alice Neel

Wahi:

One of my favorite paintings by Alice Neel is one of two self-portraits that she created. And this particular one, it’s a painting of her sitting nude in a chair. And what strikes me, in a feminist context, about this work is the unapologetic nature of her stance and her gaze, and her interaction in the painting with us as the audience.

Neel:

I had, you know, the nude portrait of myself at eighty. Mayor Koch gave me a dinner. One hundred and thirty-nine people sat down at Gracie Mansion just because I painted myself with nothing on at eighty. I took the same attitude toward myself I take to everyone, you know. It isn’t flattering. But anyway, Mayor Koch loved it, and I was in the New York Times, I was in Newsweek …

Wahi:

We often don’t see, in Western painting in particular, images of women as they’re aging. Generally what we see is women sort of in their quote “prime,” in their youth, as these sort of sexy, bodacious figures, and I think there’s a phenomenon that still exists today of the kind of erasure of women as they age. And I think this is just her pushback against it, and it’s also, you know, besides the defiant nature of it, it’s a beautiful painting.

Alice Neel (American, 1900–1984). Margaret Evans Pregnant, 1978. Oil on canvas, 57 ¾ × 38 ½ in. (146.7 × 97.8 cm). Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, Gift of Barbara Lee, The Barbara Lee Collection of Art by Women. Image © The Estate of Alice Neel

Narrator:

In interviews, Neel insisted that her gender did not shape how she painted. Here she is speaking with Terry Gross in 1981.

Terry Gross:

Do you think being a woman has affected what you choose to paint and how you choose to paint it?

Neel:

No, no, I did as I damn pleased. And purposely so. And when you’re in a room working, you don’t think about what sex you are, or at least I don’t. I don’t think there’s a woman’s world and a man’s world. I think we all have the same world.

Narrator:

And she says in an interview …

Neel:

… In fact, some man the W.P.A. I think he said, “Oh, Alice Neil, the woman that paints like a man.” But I told him, “Look, I don’t paint like a man. I paint like a woman.”

Narrator:

And in the same interview…

Neel:

… I don’t feel either that there is definite “female” painting, you know? I don’t think you could tell a man’s painting from a woman’s painting.

Wahi:

Although she does reference the expectation of what female painting would have been—so painting landscapes or ceramics or, dainty objects, still lifes. Not that there’s anything wrong with that, but I think she saw herself as transgressive and didn’t apologize for that.

Narrator:

But the public often did see her as a “woman artist.”

Neel:

Actually I painted in obscurity for years and years. I used to think the important thing is that you do a good painting. So I didn’t care what happened to it afterwards. I often just put it on a shelf.

Narrator:

That started to change in the 1960s and ’70s, when the women’s movement helped bring attention to her work.

Then, in 1974, The Whitney Museum of American Art mounted an Alice Neel retrospective. In one documentary film, she talks about this as a watershed moment.

Neel:

I tell you what that show did for me. I always felt in a sense that I didn’t have the right to paint, because I had two sons and I had so many things that I should be doing, and here I was painting. But that show convinced me that I had a perfect right to paint. I shouldn’t have ever felt that, but I did feel it. And after that show I never felt that anymore.

Narrator:

Neel struggled to reconcile societal expectations of her role as a mother and her own desire for a career as an artist. And in a practical sense, she struggled to make space for her art in the same apartment where she was raising two kids on her own. Financially, she never had the luxury of a separate studio.

She also painted women in ways they had rarely been painted before. She painted pregnant women, women giving birth, and unidealized female nudes.

Wahi:

When I think about Alice Neel’s work, it is far deeper than just what meets the eye, than just something that is a beautiful, surface-level painting.

Of course aesthetics are extremely important—that’s what brings us in. But beyond that, it’s the people who she’s portraying and their lives and the intonation that we get and the little clues that we get about who those people are as markers or monuments in history.

“Of course aesthetics are extremely important—that’s what brings us in. But beyond that, it’s the people who she’s portraying and their lives and the intonation that we get and the little clues that we get about who those people are as markers or monuments in history.” —Jasmine Wahi

Neel:

You don’t live in the world alone. But you see now, for instance, I know figurative painters, that will take the formation of a figurative painting done maybe fifty or one hundred years ago, and then they’ll fit modern figures into that. I never do anything like that. Because I think the mood of today, the history of today, has its own rhythm. And the people you see today, you should paint the way they are now.

Wahi:

And what I think is so beautiful about her work is the people that she’s marking are not necessarily the people who you would hear about on the news or in the mainstream or in the media. They’re just everyday people.

Narrator:

To be a woman who chose to paint “everyday” people, of different races and ethnicities and from all economic backgrounds …

Wahi:

… at that time and maybe even now is a political act. And I think although many people are apt to think of portraits simply as “just portraits”—they’re never just that.

Narrator:

It’s impossible to divorce Neel’s art from her politics. She participated in progressive political movements throughout the twentieth century. She was sympathetic to Communist ideals for most of her life. She was close to union organizers. And later …

Neel:

But then one day I picketed with this big Women’s Lib March that went down Fifth Avenue …

Narrator:

In the late 1960s and early ’70s, she joined protests organized by a group called the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition in front of major museums, including The Met.

Photo © The Estate of Alice Neel. Courtesy of The Estate of Alice Neel and David Zwirner

Neel:

Yeah, I picketed The Whitney because they were being unfair to Blacks.

Narrator:

For artist Miguel Luciano, her art and life provide a call to action.

Miguel Luciano:

The work encourages us to get involved in social justice. You know, her life was a model of that in many ways, you know, the causes that she supported and that she believed in. So there is an opportunity to sort of look at the arc of her life and her work from this period, and think about how we ourselves can move in the world with deeper empathy and deeper commitment to social change and social justice. And that’s something I think that everybody should consider, when seeing this work.

Narrator:

In the next chapter, you’ll hear more from Luciano, and how New York City shaped Neel’s personal life and her art.

Miguel Luciano on Spanish Harlem and Alice Neel’s Community

Narrator:

Alice Neel grew up in a small Pennsylvania town called Colwyn. But she wasn’t a fan of small-town living.

Neel:

I hated it. You know what benighted little towns are like? Oh, I used to sit on the front porch and try to stop my heart from beating and my blood from circulating, I was so bored.

Narrator:

But New York City? That was something else. Neel lived there nearly her entire career, except for a few short years in Pennsylvania. The city, filled to the brim with people of every kind, was an endless source of subject matter. Later in life, she told Terry Gross:

Neel:

I must tell you a good quote of Cezanne’s. He said, “I like to paint people who have grown old naturally in the country.” I’m just the opposite. I like to paint people torn apart by the city, and you know, in the rat race with all the struggle that goes on.

Narrator:

In the early 1930s, Neel lived downtown, in Greenwich Village, the epicenter of bohemianism and progressive politics. But in the late 1930s, she fell in love with a Puerto Rican musician named José Santiago Negrón. And in 1938 the two of them moved uptown, to Spanish Harlem.

Here’s Miguel Luciano, an artist who was born in Puerto Rico and lives in New York.

Alice Neel (American, 1900–1984). Two Girls, Spanish Harlem, 1959. Oil on canvas, 30 × 25 in. (76.2 × 63.5 cm). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Gift of Barbara Lee. Image © The Estate of Alice Neel

Miguel Luciano:

Spanish Harlem, El Barrio, East Harlem, had become the symbolic center of the Puerto Rican community in New York at a time where, between 1940 and 1960, about a million Puerto Ricans migrated to the United States, to fill factory and farm jobs, you know, looking for work.

Narrator:

Luciano is a multimedia artist, working across painting, sculpture, photography, installation, and more.

Luciano:

I live and work in East Harlem and have been working on public art projects in East Harlem related to the activist history of our neighborhood. I did a big project called Mapping Resistance, The Young Lords in El Barrio, which was about the activist history of the Young Lords.

Narrator:

Meanwhile Alice was …

Diamonstein-Spielvogel:

… born in Pennsylvania, the granddaughter of a Civil War veteran.

Neel:

Yes, that’s right. Both sides

Diamonstein-Spielvogel:

Well on one side, and on the other side of your family, a signatory of the Declaration of Independence,

Neel:

That’s right, that’s right.

Luciano:

You know, she fell in love with a Puerto Rican man, she moved to El Barrio, and I think she really fell in love with East Harlem and with the people of El Barrio at the same time, which I can totally understand. And she stayed there for, you know, almost twenty-five years.

Narrator:

Through José, the father of her son Richard, Neel became part of an extended Puerto Rican family.

Alice Neel (American, 1900–1984). Mercedes Arroyo, 1952. Oil on canvas, 25 × 24 ¼ in. (63.5 × 61.3 cm). Collection of Daryl and Steven Roth. Image © The Estate of Alice Neel

She felt a great deal of respect for the community that she lived in and for the people that she was around. And you can see and feel that love and respect in the paintings. —Miguel Luciano

Luciano:

She felt a great deal of respect for the community that she lived in and for the people that she was around. And you can see and feel that love and respect in the paintings. And that’s very, very different than someone who is painting people in communities that they don’t live in, right? Or communities that they’re not connected to.

Narrator:

Living in East Harlem, Neel encountered many people who were deeply involved in activism and in civil rights, and she would paint them, too.

Luciano:

One of the paintings that has long been a favorite for me is the painting of Mercedes Arroyo.

Narrator:

In that painting, we see a woman seated in a chair. Her head is tilted upwards, and her gaze is directed upwards too, towards something we can’t see.

Luciano:

And I love that it’s a beautiful painting of a beautiful Puerto Rican woman, who was an educator, an activist, an organizer. And as a representation of our community, I’m very proud, you know, that she’s been recorded that way.

Alice Neel (American, 1900–1984). T.B. Harlem, 1940. Oil on canvas, 30 × 30 in. (76.2 × 76.2 cm). National Museum of Women in the Arts, Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay. Image © The Estate of Alice Neel

Narrator:

Luciano also talked about another painting …

Luciano:

… called T.B. Harlem. And it was about tuberculosis and really the epidemic of tuberculosis in the community at that time.

Neel:

I painted this in 1940. Statistically Spanish Harlem had the highest T.B. rate of any place in the city. This was a young man about 23. He recovered.

Narrator:

The painting shows José’s brother, Carlos, recovering from surgery to treat his T.B. He’s a young-looking man with dark circles around his eyes. He’s propped up on a bed or couch, and a large white bandage covers a wound on his chest.

She also painted …

Neel:

… his wife, a very courageous woman and three of his children. I think he had five altogether.

Luciano:

I think of the words of Nina Simone that talked about the responsibility of artists to reflect the times that we live in. And I think that Neel in her own way was doing just that; she was recording the history that she was living, and reflecting the conditions of the people around her.

It’s sometimes bittersweet when I think about it because it’s still a kind of representation through the lens of a white artist rather than through the lens of someone who is Puerto Rican from that same neighborhood, for example. And there were artists in that neighborhood at that time who have not received the same kind of attention.

Narrator:

Luciano talked about some of those Puerto Rican artists. Like Hiram Mirastany, a photographer who documented life in East Harlem during the 1960s and ’70s. Or Rafael Tufiño, who was known as el pintor del pueblo, “the painter of the village.”

Luciano:

Nevertheless, I’m grateful for Alice Neel’s images. And I’ve been very moved by them, because they’re windows into a history that has been recorded in her work. And it’s not an arbitrary history, it’s a political history.

Neel:

I see art itself as history. I think that’s one of the functions of art.

I always did everybody. Even the oldest ones. It’s just that I found these people and their fate very interesting. I have this overweening interest in humanity, and even if I’m not working, I’m still analyzing people. It’s built in.

This podcast is supported by Bloomberg Philanthropies.

Audio Courtesy:

Alice Neel © 2007 SeeThink Films. Directed by Andrew Neel.

Alice Neel: They Are Their Own Gifts, 1978. Courtesy of Lucille Rhodes and Margaret Murphy.

Television interview with Alice Neel, from the television series “Inside New York’s Art World, 1978,” courtesy of Dr. Barbaralee Diamonstein-Spielvogel, Interviewer/Producer.

Audio provided by the Barbaralee Diamonstein-Spielvogel Collection, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University.

“Interview with Alice Neel conducted by Yetta and Werner Groshans.” Courtesy of Smithsonian Institution Archives, Werner and Yetta Groshans papers, 1928–1997.

Marquee: Photograph of Alice Neel, 1944, by Sam Brody. © The Estate of Alice Neel. Courtesy of The Estate of Alice Neel and David Zwirner