When I arrived at The Met on June 3, 2019, it marked the culmination of a long-held dream. I grew up in New York City, so The Met had always been a special and familiar part of my world. In fact, it was during a field trip to The Met, while walking through the Egyptian wing, that I decided that I wanted to be a historian when I grew up. At eight or nine, I could not have consciously known that I was speaking my future into existence and that many years later I would fulfill my dreams and start my career as a fashion and cultural historian at The Costume Institute, located just below my feet, under the very same Egyptian galleries I was standing in.

Despite many previous visits to The Met, that first Monday in June was markedly different. For the first time, I was not entering the Museum as a visitor. Instead, I was entering as a fellow custodian with a new, meaningful, and challenging responsibility. I was just two weeks shy of my college graduation and extremely nervous to begin living my post-grad life. Alongside my anxiety, however, was an overwhelming feeling of gratitude to start this new chapter of my life at The Met—the place of my dreams and one that already felt kind of like home.

The author answering questions after one of their Intern Insights tours. Photo by Celia Hartmann

I remember lining up outside with the other interns before entering the Museum. Everyone was quiet, but the air was charged with bubbling excitement as people were inquisitively and enthusiastically taking each other in. There were interns from all over the country and the world with various backgrounds and interests. I expected to meet a group of people with similar academic backgrounds to my own, however, many people brought knowledge from disciplines outside of art history and museum studies, such as library science, digital communications, and even theology. The diversity of experiences made for dynamic conversations during our Friday seminars and an environment where we constantly learned from each other. This was especially helpful during the planning of our Intern Insights tours, which was a slightly vulnerable time for everyone.

Mr. and Mrs. I. N. Phelps Stokes, 1897 America. John Singer Sargent. Oil on canvas, 84 1/4 x 39 3/4 in. (214 x 101 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Edith Minturn Phelps Stokes (Mrs. I. N.), 1938 (38.104)

Our Intern Insights tours were an opportunity for us to prepare 45-minute themed public tours, using three to four objects from The Met collection. My first thought was to develop something related to my own research in the history of dress and fashion. With so many portraits in the collection, I thought it would be easy enough to find compelling representations of historical dress and create a theme around the sitters’ clothing, and perhaps, what they, in collaboration with the painter, were endeavoring to signify about their identities. The first object I had in mind was the 1897 Sargent double portrait in the American Wing, titled Mr. and Mrs. I.N. Phelps Stokes. Sargent’s portraits are rich with subliminal discourses about fashion and identity, particularly because after closely studying the character of his subjects, he carefully chose the outfits in which they appeared. I am always drawn to Mrs. Stokes’ sporty and androgynous ensemble and her centrality within the composition. It was commissioned by a friend of the couple in celebration of their wedding. Despite this, and despite the fact that it is her husband’s name that appears in the title, she remains the unequivocal subject, with her husband standing in her shadow—a stand-in for their absent Great Dane.

Left: Enthroned Virgin and Child, ca. 1210-20 North French. Oak with traces of polychromy, Overall: 48 1/2 x 20 1/4 x 19in. (123.2 x 51.4 x 48.3cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of George Blumenthal, 1941 (41.190.283). Right: Clothing the Naked, ca. 1661 Flemish. Michiel Sweerts. Oil on canvas, 32 1/4 x 45 in. (81.9 x 114.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Charles Wrightsman, 1984 (1984.459.1)

After observing the painting in the gallery for some time, I came away with a different and simpler topic idea: couples. Rather than facilitate a tour specifically about fashion, I could find depictions of couples of all kinds and ask the group to use visual clues—including dress—to discern what kind of relationship the two rendered figures might share. I stuck with Mr. and Mrs. Stokes as the third and final object on my tour and added a stoic Enthroned Virgin and Child statue in Medieval Art, and a Dutch painting by Flemish artist Michiel Sweerts, titled Clothing the Naked.

Aside from our tours, we each had placements in one of the Museum’s many departments. My placement was in The Costume Institute, where I worked in the library with Assistant Museum Librarian Julie Lê. To be there every day as a member of staff was a truly surreal and special experience. I remember being awestruck by the powerful and emotional displays of the 2011 Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty exhibit, which was the first Costume Institute exhibition I remember seeing. It didn’t occur to me, however, that working at The Costume Institute was a potential career path I could take until I stumbled across a copy of D.V. just a few months later.

As a high-school student, reading Diana Vreeland’s idiosyncratic autobiography informed me that I was not alone. I was pleased and inspired to discover that there were other people who experienced history through a passionate and serious interest in clothing the way I did. I realized I could marry my passions for art, history, fashion, and culture together both professionally and academically. Up until that point in school, I had to negotiate for every opportunity I could to write about and research fashion history. It taught me how to be persuasive in an academic world that saw my passion as a novelty instead of a substantial discipline. It was lonely, and as such, I was grateful to finally find a path forward where I could hope to meet a community of like-minded people. I knew then that I wanted to dedicate my studies to becoming an art and fashion historian, and I knew The Costume Institute was the place I wanted to go.

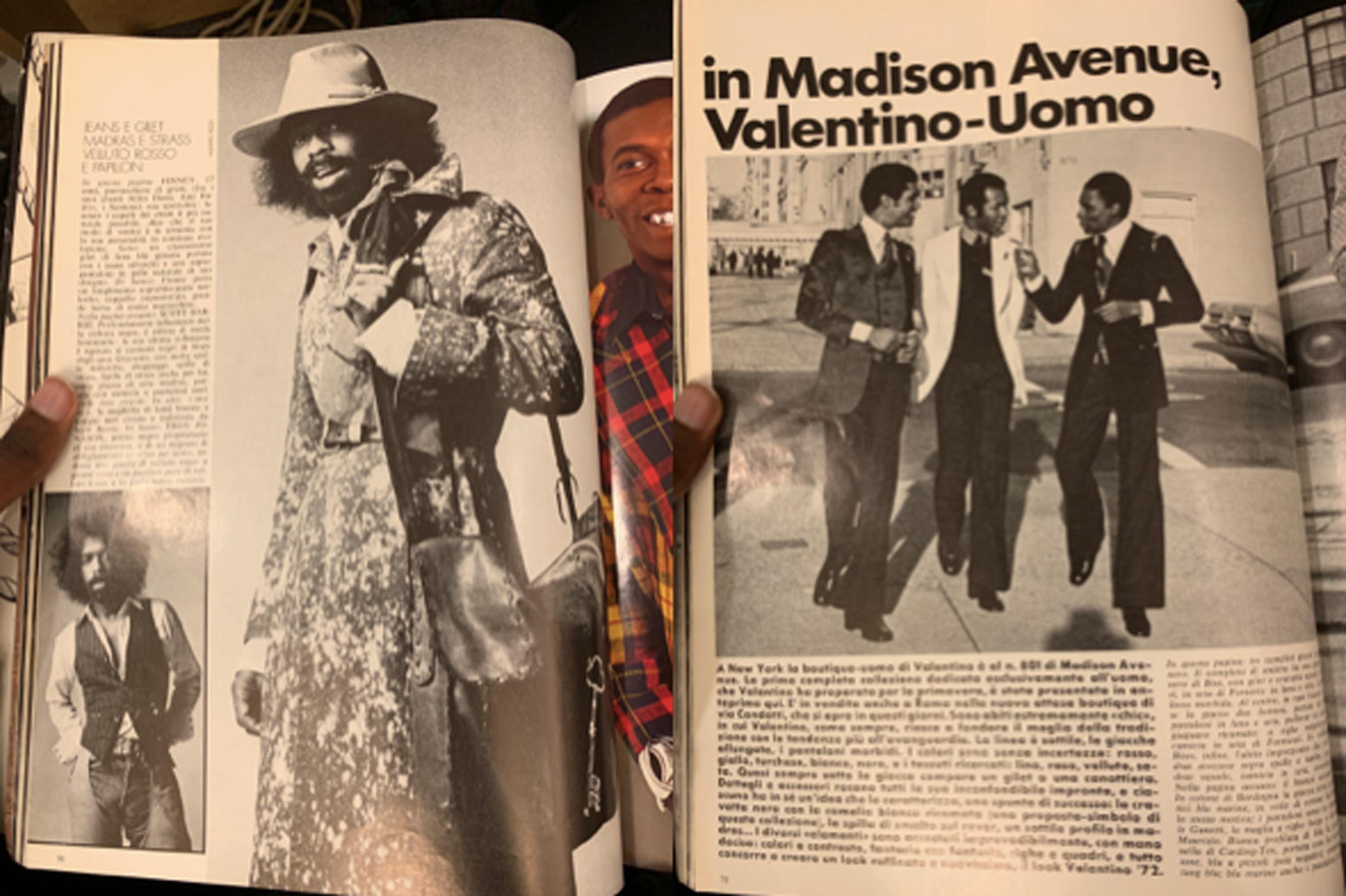

In The Costume Institute Library, my daily tasks included caring for the over thirty thousand books and objects. Whether it was finding new housing for books and magazines or reshelving and cataloging items, I got to see and handle one-of-a-kind objects that were fantastic to get lost in. I loved flipping through vintage issues of Jet Magazine, British and American Vogue from the 1930s and ’40s, early print editions of Fashion Theory, a special 1972 edition of L’uomo Vogue dedicated to Black fashion in New York, and many other treasures.

L’Uomo Vogue, February - March, 1972

Some of my favorite objects were the mid-century collaborations between Roger Vivier and Dior, and also a pair of evening sandals with genuine ceramic Wedgwood jasperware heels made by Sir Edward Rayne.

Left: Roger Vivier shoes in the Collections department of The Costume Institute. Photo by author. Right: Evening sandals, 1970s British. Sir Edward Rayne. Leather, ceramic. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Nancy Kirschbaum, 1993 (1993.395.9a, b). Photo by author

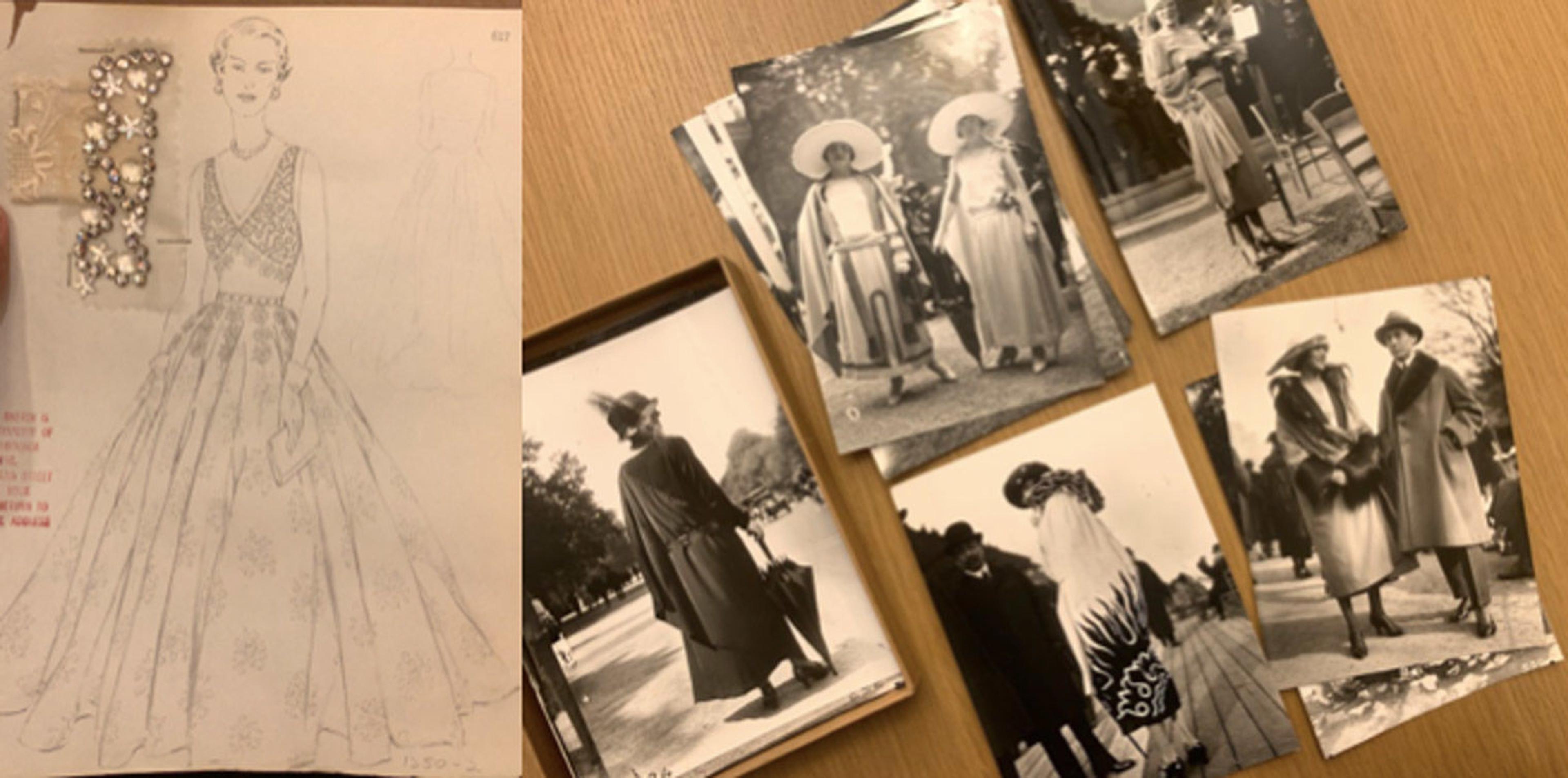

Much of my time in the library was spent digitizing original sketches by the American couturier Mainbocher and early twentieth century photographs by pioneers of street fashion photography, the Frères Séeberger. These photographs, many of them candid, were wonderful to look at and a great supplement to more standardized fashion histories, which tend to eschew representations of unique personal style in favor of more popular historical and generational trends.

Left: Original sketch from American couturier Mainbocher. Photo by author. Right: Compilation of street-fashion pictures taken by the Frères Séeberger. Photo by Julie Lê

My long-term project was the processing of a recent donation to the library from designer Todd Oldham. In undertaking this task, I worked alongside former Assistant Archivist Celia Hartmann for several months as we sorted through the contents of the collection piece by piece. We received many boxes of video tapes, clippings, sketches, and photographs. Each item was then carefully sorted and cataloged digitally using Archivist’s Toolkit.

My favorite part of the process was sorting through and housing the collection of polaroids. Going through those images was like uncovering a time capsule of the best of the nineties. My favorite finds were the shots of Naomi Campbell and Alek Wek, both young and baby faced. These photographs were not the glossy and highly produced images most of us are used to seeing. Instead, they were snapshots, indexical to the behind-the-scenes moments with barefaced models and a designer at the height of their creative process. At the end of sorting, we compiled a detailed list of every group of materials, complete with dates, titles, and any other information we could find, and then published it in a digital Finding Aid. It was a tedious process, but a rewarding and exciting one as well.

Left to Right: Model Naomi Campbell in Todd Oldham Spring 1996, Polaroid print. Model Alek Wek in Todd Oldham Spring 1998, Polaroid print

In late February 2020, we got news of a COVID-19 outbreak. There was not a great deal of information available, so it was difficult to gauge how critical the situation was. No one could have predicted what followed. At first, we were asked to come into the Museum if we felt comfortable, and then very shortly after, we were asked to stay home … for two weeks. While we assumed we would soon be back to work like normal, sadly, those two weeks turned into over a year and counting. As an intern, like many other temporary and hourly Museum workers, and people all over the world, I was laid off.

I was deeply disappointed to leave with three months of my internship still left and sad to leave my work and colleagues behind. I knew I would miss seeing my friend and mentor Julie every week. In the midst of my disappointment, however, I could not complain. I started my position at the Museum expecting to stay only ten weeks, which then turned into six months, which turned into a year … almost. I loved every minute of my experience.

When I look back over a year later, my favorite experiences were meeting colleagues who were generous with their time, insights, and encouragement, and who shared with me in great detail the work they do every day. I also relished the opportunity to deeply engage with one of the most unique and comprehensive collections of books and resources related to dress and fashion in the world. I loved getting to witness exhibitions in The Costume Institute develop from the planning stages all the way through to their fruition. And I loved engaging guests of all ages as interlocutors in conversations about fashion and identity. If I had any advice to future interns, it would be to chat with and get to know as many people as you can and savor every moment because your experience will go by much more quickly than you can imagine!

Picture of author and Julie Lê

An update from the author: I am happy to share that my journey at The Costume Institute has presently come full circle, and as of September 2021 I am the department’s newest Research Assistant!