Before I transitioned into a career in the field of library and archives, I served seven years on active duty in the US Air Force as an Arabic Cryptologic Language Analyst. Therefore, as a veteran—and because November is both the month in which we celebrate Veterans Day (November 11) and National Native American Heritage Month—I thought it fitting to focus this essay on Native American artists whose art careers have in some way been influenced by military service. My intention here is not to present a chronological account of the role Native Americans have played in the history of the US armed forces. For those who are interested in learning more about this history, Watson Library has recently acquired a copy of Why We Serve: Native Americans in the United States Armed Forces, a catalog which accompanied an exhibition of the same title that took place at the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) from November 11, 2020 to February 28, 2021.

It also isn’t my aim here to delve into the complexities and ambiguities of the military as an institution, though this is certainly important to keep in mind in a discussion about marginalized communities of color whose relationship with the US military has been historically complicated and at times violent. Rather, my aim here is to celebrate a very small selection of Native American artists who have served in the military by presenting a number of relevant titles that stood out to me throughout my time working on the National Endowment for the Humanities project, “Research and Outreach: Increasing Representation of Indigenous American, Hispanic American, Asian American and Pacific Islander artists in The Met’s Thomas J. Watson Library.”

Why We Serve: Native Americans in the United States Armed Forces, by Alexandra N. Harris and Mark G. Hirsch (Washington, DC: National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, 2020)

As I researched more than two thousand names of Indigenous and Native American artists as part of the NEH project, I was surprised at how many have served in the military. There are those who were drafted and those who enlisted voluntarily, and among them are veterans of the Civil War, World War I, World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War. Some examples include Rose Kerstetter (Onyota'a:ka [Oneida]; Haudenosaunee [Iroquois]; WWII veteran), Jesse Cornplanter (Onödowa’ga [Seneca]; WWI veteran), Oscar Howe (Ihaƞktoƞwaƞ Dakota Oyate [Yanktonai Dakota]; WWII veteran), Acee Blue Eagle (Maskoke [Muscogee Creek]; Pawnee; WWII veteran), James Auchiah (Ka'igwu [Kiowa]; WWII veteran), Steven Yazzie (Diné [Navajo]; Kawaik [Laguna]; Gulf War veteran), and Benjamin Harjo (Seminole; Absentee Shawnee; Vietnam War veteran), among many others.

In this post, I will highlight four Native American artists and veterans whose stories struck me the most: Eva Mirabal, Lloyd Kiva New, Carl Nelson Gorman, and Michael Naranjo.

Eva Mirabal (Taos Pueblo, 1920–1968)

Of these four artists, Eva Mirabal (Taos Pueblo), also known as Eah-Ha-Wa, most resonated with me. For one, we have both served in the U.S. military as women of color. In addition, we have both used our military experiences and cultural heritages as subject matter in the creation of art. Mirabal was a painter, muralist, and cartoonist, and her work decorates the walls of many buildings, including Wright-Patterson Air Force Base and the library of the Veterans’ Hospital in Albuquerque. In 1943, she joined the Women’s Army Corps (WAC) at the age of 23 and served during World War II until her discharge in 1947. During her time in the WAC, she worked as the corps’ only full-time artist and designer, where she created a weekly comic strip titled G.I. Gertie as well as a number of war posters and murals. According to the publication Eva Mirabal: Three Generations of Tradition and Modernity at Taos Pueblo, it is quite likely that Mirabal was the very first Indigenous woman comic artist to be published.

Watson Library already had a copy of Eva Mirabal: Three Generations of Tradition and Modernity at Taos Pueblo prior to the start of our NEH grant project, but I still think this book deserves a shout out here!

Cover and excerpt from Eva Mirabal: Three Generations of Tradition and Modernity at Taos Pueblo, by Lois P. Rudnick, with Jonathan Warm Day Coming (Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press, 2021)

Lloyd Kiva New (Cherokee, 1916–2002)

Lloyd Kiva New (Cherokee) recently had two of his fashion designs on view at The Met as part of The Costume Institute’s In America: An Anthology of Fashion exhibition, which ran from May 7 to September 5, 2022. In addition to developing a successful career as a prominent fashion designer, New was also a veteran of the United States Navy who served during World War II. He enlisted in the Navy in 1941, where he served as an official ship artist for the USS Sanborn. While working as an artist on the Sanborn, he completed a mural aboard the ship, and he also sketched and painted what he witnessed while traveling on board. His sketches serve as a memory of the ship’s journey.

According to the publication Lloyd Kiva New: A New Century (recently acquired by Watson as part of the NEH grant project), “On February 18, 1945, the Sanborn moved troops to and from the island of Iwo Jima, where a decisive battle was fought against Japanese forces. New’s first person imagery of the Battle of Iwo Jima and perspective from aboard a landing craft provide life and color to a story primarily documented through black and white photographs and newsreels… Lloyd New’s wartime watercolor paintings are cherished as works of art and part of the historical record.” His watercolor painting Battle of Iwo Jima (now held in the Institute of American Indian Arts [IAIA] Museum of Contemporary Native Arts) is included among the works featured in the book, along with photographs of his textile and clothing designs.

Also recently acquired as part of the NEH grant project is The Sound of Drums: A Memoir of Lloyd Kiva New, which includes New’s personal anecdotes and reflections on his time in the Navy. It also features photographs of him on board the Sanborn, as well as images of some of the artwork that he created during this time based on his experiences at Iwo Jima (courtesy of the IAIA).

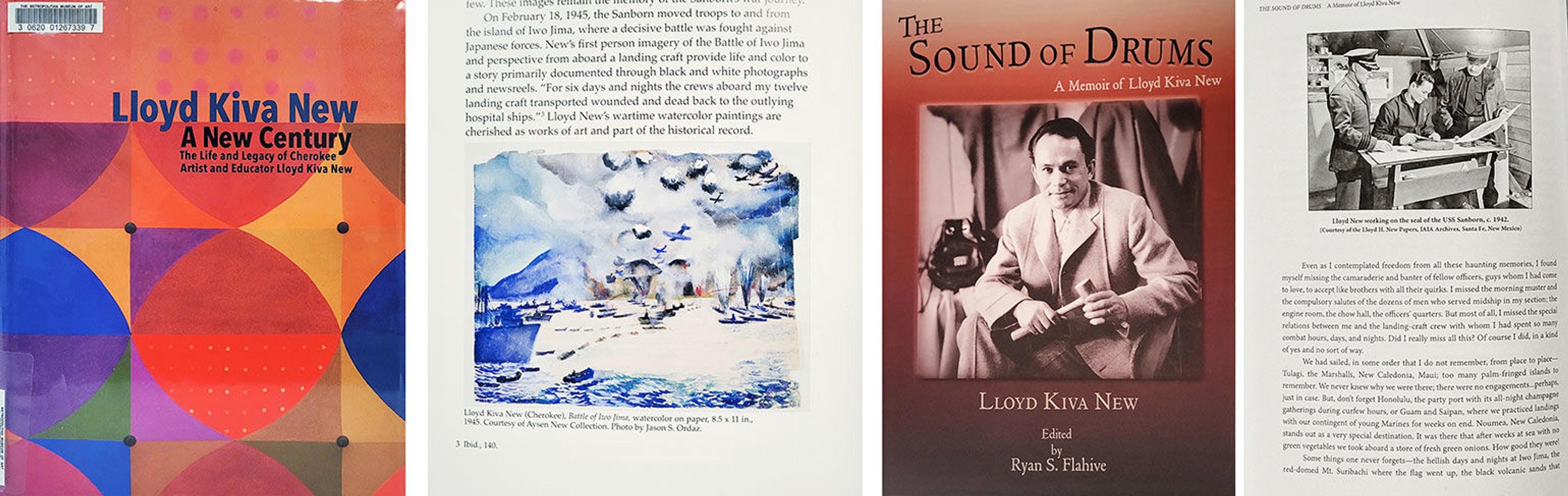

Left: Lloyd Kiva New: A New Century: The Life and Legacy of Cherokee Artist and Educator Lloyd Kiva New, produced through a collaboration between the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture (MIAC), the IAIA Museum of Contemporary Native Art (MoCNA), and the New Mexico Museum of Art (NMMOA) (Santa Fe: Art Guild Press, 2016). Right: The Sound of Drums: A Memoir of Lloyd Kiva New, by Lloyd Kiva New, edited by Ryan S. Flahive (Santa Fe: Sunstone Press, 2016)

Carl Nelson Gorman (Diné [Navajo], 1907–1998)

Prior to beginning his career as an artist, Carl Nelson Gorman (also known as C.N. Gorman) served in the US Marine Corps during WWII as one of the 29 original Navajo Code Talkers. From 1942 to 1945, Gorman worked as part of an elite team of Diné (Navajo) translators who encrypted military intelligence into uncrackable codes based on the Navajo language. After his discharge from the Navy, he used his GI Bill education benefits to study art at the Otis Art Institute (known today as Otis College of Art and Design). As an artist, Gorman worked in various media including painting, printmaking, ceramics, tile, and jewelry. His son, Rudolf Carl Gorman (also known as R.C. Gorman, 1931–2005), would follow in the artistic footsteps of his father, and the two exhibited together on multiple occasions.

If you’re interested in military history or historical photographs, it’s worth taking a look at the book Carl Gorman’s World (already in Watson Library’s collection prior to the NEH grant project), which contains many photos of Gorman from his time in the military and as a veteran. In addition, Watson Library also recently acquired a copy of Power of a Navajo: Carl Gorman: The Man and His Life as part of the grant project.

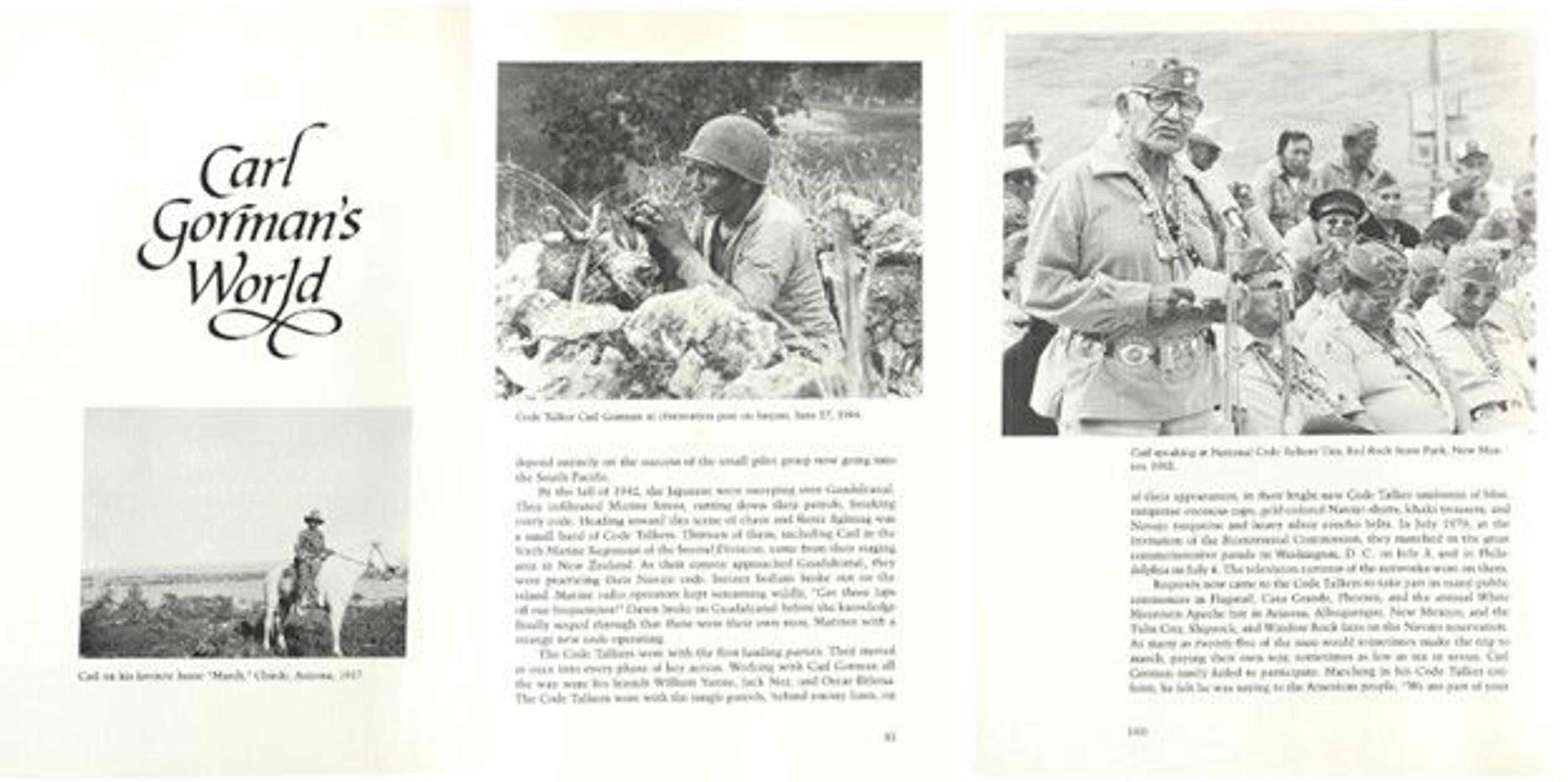

Excerpts from Carl Gorman's World, by Henry Greenberg and Georgia Greenberg (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1984)

Michael Naranjo (Khaʼpʼoe Ówîngeh [Santa Clara Pueblo], 1944–)

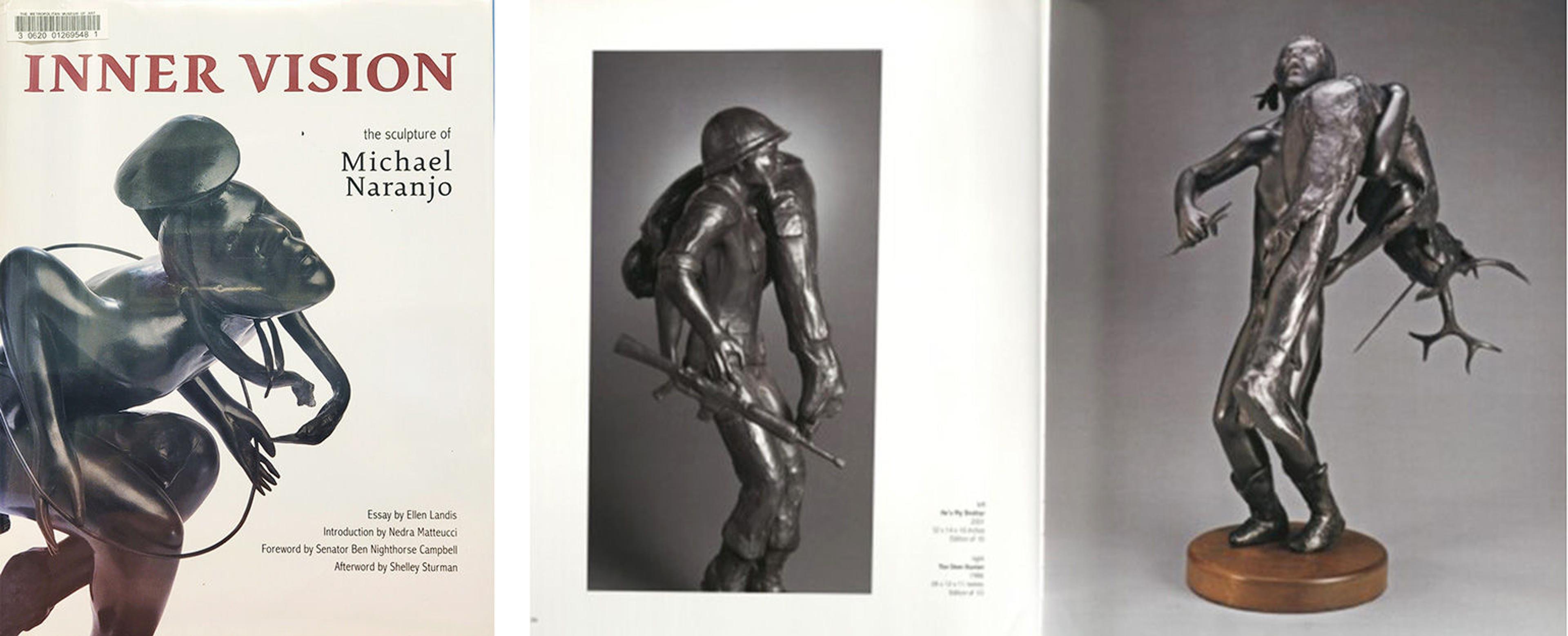

Michael Naranjo is an internationally acclaimed sculptor and veteran with a disability whose work is held in locations throughout the world including the Vatican, the White House, Eiteljorg Museum, and the Heard Museum in Phoenix, Arizona. He was drafted into the Army during the Vietnam War, and in 1968 he suffered a grenade injury that resulted in the loss of his eyesight and incapacitated his right hand. Despite losing his vision, Naranjo engaged in sculpture during his convalescence period, which rekindled his childhood ambition of becoming a sculptor like his well-known potter mother Rose Naranjo (1917–2004). He has been sculpting ever since, and his art career has flourished for over five decades.

Naranjo uses touch and memory to create his sculptures, utilizing his left hand without the aid of sculpting tools. In an essay in the publication Inner Vision: the Sculpture of Michael Naranjo (newly acquired through the NEH grant), Ellen Landi wrote “His left hand works as his ‘eyes,’ but it is the vision in his mind that carries through to the vision in his hand…”. His work includes subjects of Native American dancers, women, children, animals, and Army soldiers.

Inner Vision: The Sculpture of Michael Naranjo, with managing editor Laurie Naranjo and edited by Lisa Fisher (Singapore: Imago, 2012)

For more highlighted titles that were acquired as part of the NEH grant project, I highly recommend checking out our culminating exhibition, Past/Present/Future: Expanding Indigenous American, Latinx, Hispanic American, Asian American, and Pacific Islander Perspectives in Thomas J. Watson Library, which is currently on view at Watson Library until January 3, 2023. I also recommend taking a look through Watson Library’s other heritage group indexes: Index of Latinx and Hispanic American Artists, Index of Asian American and Pacific Islander Artists, and Index of African American Artists. Additionally, over the past year many of the acquisitions related to the NEH grant project have been shared to our Instagram page (@metlibrary).

Finally, Watson Library will be launching its Index of Indigenous and Native American Artists at the end of November, a resource for identifying relevant publications in Watsonline which will include the names of over one thousand Indigenous and Native American artists.