There is a scene in the 1995 film Waterworld, a science-fiction tale about a dystopian world submerged in an endless ocean, in which a character known as ‘The Drifter’ shows the protagonist (played by Kevin Costner) a crumpled piece of paper. The Drifter exclaims, “It’s paper. Have you ever seen paper? Look at it.”

That scene resonates with me because it captures an ever-present reality. The Pacific region and its inhabitants are unique, vibrant, living, and enduring in the face of overwhelming challenges. And despite all our efforts to preserve and protect our cultural heritage, global climate change threatens to erase the objects and records that hold our stories and traditions.

Since January 2020, I have led a project that speaks to aspects of this reality. The Pacific Virtual Museum, which is funded by the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs & Trade and implemented by the National Library of New Zealand in collaboration with the National Library of Australia, makes visible and accessible the digitized cultural heritage of the Pacific, for people in and of the Pacific. As Opeta Aleafaio, director of the National Archives of Fiji, has said: “It’s one thing for Pacific people to know they had their culture taken from them. It’s another thing entirely for them to not know the artifacts and records of their culture exist.”

Homepage of the Pacific Virtual Museum

The cultural heritage institutions of the former and existing colonial powers hold many items, objects, and records from the Pacific locations. Most Pacific people are unaware of this reality. As a bridge to the worlds of museums, galleries, and libraries, we enable Pacific people to access records from the online digital collections of our content partners, to utilize and engage with the source records.

Like sites such as Digital Public Library of America, Europeana and Trove, we leverage our content partners’ metadata, aggregating those records in a site designed to work well for people in the Pacific, where the internet is most frequently accessed via low-bandwidth connections on mobile devices. Most objects are accompanied by an image, a contextual description, date, collection name, and source. The metadata we display is linked to the databases of our content partners. Our scripts run regularly, so when our partners update or correct their metadata, we reflect these changes.

We acknowledge that we present a copy of the content partners metadata. They always remain the holder and retain authority over the metadata. In practical terms, this approach means that, in the event that our site becomes inaccessible from the internet, the source metadata is not lost, as it remains with the content partners and accessible via their platform.

This distinction is crucial for us because of the Pacific-wide experience of colonialism and removal of culture. The Pacific Ocean covers 33% of the surface of Earth’s plane. But the Pacific Islands across that ocean - their locations, cultures, and people - are mostly invisible to the rest of the world, being as they are almost infinitesimally small and scattered. When the islands and their cultures are acknowledged, they are often seen as singular, remote, exotic, and idyllic. But they are not invisible, nor should they be romanticized.

As Fijian archaeologist and curator Dr. Tarisi Vunidilo said to me, “Pacific people were, pre-contact with the West, astronomers, food scientists, mathematicians, sailors, artists and navigators—all on our terms and in our own right.”

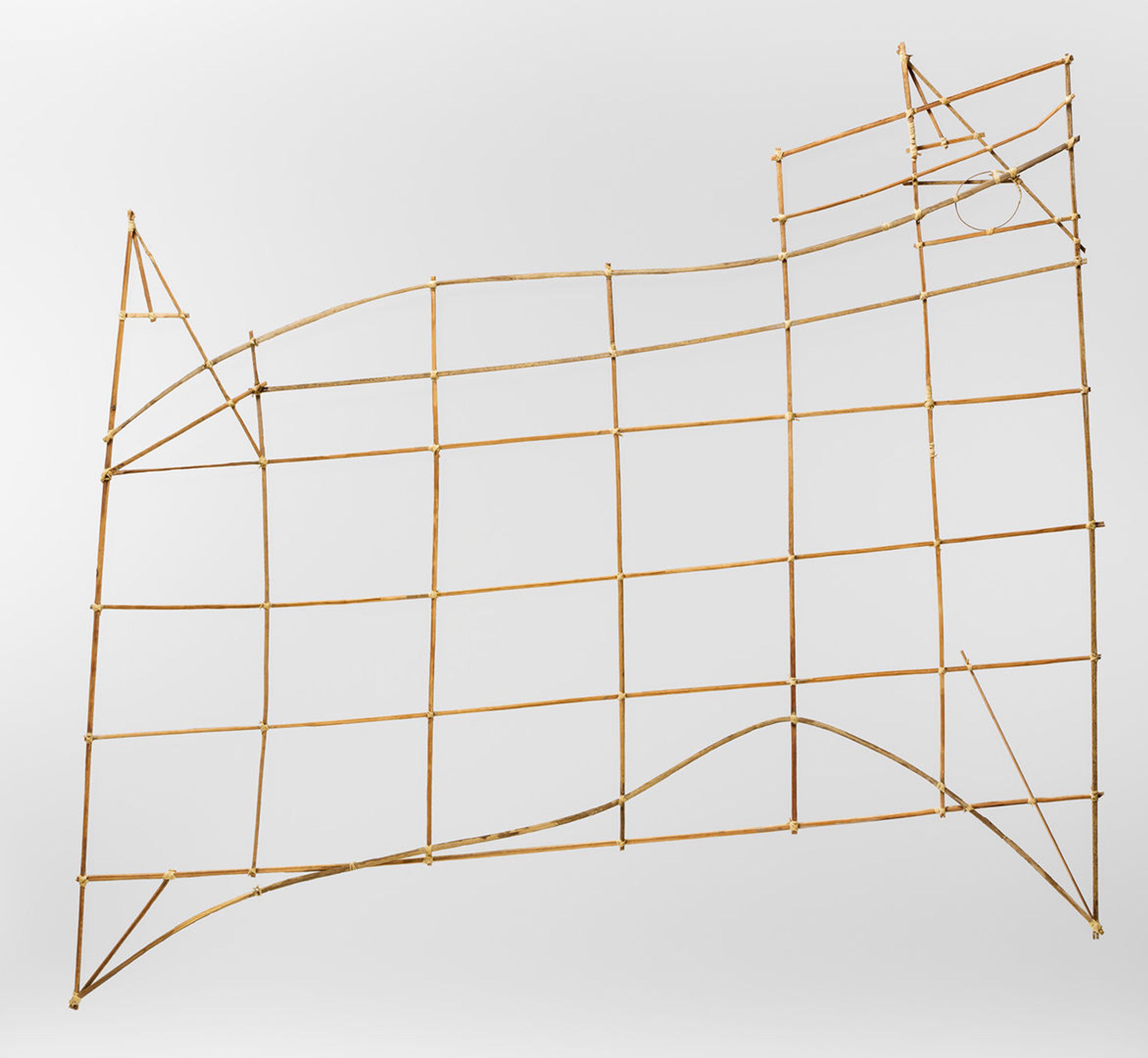

Four hundred years of colonialism have abetted the erasure of Pacific culture. Micronesian stick charts, such as this one from Auckland Museum, are my favorite example of this phenomenon of ‘forgetting of how we are.’ These stick charts enabled Micronesian people to navigate across the ocean using their understanding of ocean swells, currents and the impact of islands and atolls on these. They were able to do so for many years before the arrival of Europeans.

Navigational Chart (Rebbilib), 19th–early 20th century. Republic of the Marshall Islands, Marshallese people. Coconut midrib, fiber, H. 35 1/4 x W. 43 1/4 x D. 1 in. (89.5 x 109.9 x 2.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Gift of the Estate of Kay Sage Tanguy, 1963 (1978.412.826)

A few months ago, The Met shared with me the episode of Immaterial about Jade, which tells the story of a Māori hei tiki neck ornament from Aotearoa New Zealand. The object, made from pounamu jade, inspires a short discussion of how pounamu is a “taonga,” a word meaning “treasure” that is both a noun and a verb. I was struck by how closely that language matches the way many Western organizations treat these Pacific records and objects: as treasures to be held, to be cataloged and, to be protected.

And while many are delicate, unique, and deserve to be protected, if we consider taonga as a verb—to be treasured in an active fashion—how does that change how we treat these digital records?

Does it change what we define, consider, and accept as cultural heritage?

Does it change how we support those who hold this cultural knowledge?

Does it change the relationships and skills we value in our cultural heritage institutions?

Because if these records, objects, and items are secured in storage, far from their origins and the knowledge that guides their use, and far from those who would learn from them, then I believe they lose their value.

For Pacific people, culture is a living process. The value of many of these items is in their being and doing. Damon Salesa, vice chancellor of the Auckland University of Technology, said during one of our early co-design discussions, “It’s great that museums hold these ‘i`e’ [tapa beaters], beautifully photographed and cataloged. But in Samoa, they sit on the kitchen shelf until they’re needed to make tapa.”

Cultural heritage is not inherent in the guagua', the tapa beater, or the liku simply because they exist. Their cultural value is in the process by which they are created and used by their practitioners, in the relationships that are enabled because they exist, and in the way they extend people’s knowledge and understanding. If they are not seen as part of a living culture and the processes and practices of that culture, they become by default only objects of a past that no longer exist.

If we see them only as artifacts, we deny the viability and existence of these cultures in our present time. Pacific cultures do exist and are being revitalized in small, discrete and powerful ways: in language, in care for land and food preparation, in ocean navigation, in canoe and vaka creation, in craft such as weaving, pottery, and carving. As well as these traditional forms, Pacific cultures and people are informing and influencing contemporary arts and design, filmmaking, science and sports. As Dr. Tarisi said: “on our terms.”

We tried to capture this power of connection in our launch video for digitalpasifik.org, enabling generations of Pacific people to engage with cultural experiences that are often far removed from museums:

Our hope is that this project can continue to enable Pacific people to find, access and make use of the many aspects of their culture, history and heritage. To shine light anew on the international museums, galleries, libraries and institutions that hold and care for these records. To foster new relationships between these worlds.

To allow Pacific people to be filled with wonder—and, potentially, some sadness—as they seek out and find these things. But also to carry hope forward and forge links with the places, people, and practices across the ocean with whom they are connected. To uplift knowledge, awareness, and mana.

Additional Resources

Instagram: @pasifikavisuals, @archiveples, @lagimaama

Youtube: Dr. Tarisi Vunidilo, NGO Pasifika Renaissance

Sites: Memoirs Pasifika, CoconetTV

UNESCO: Carolinian Wayfinding & Canoe Making

Daren Kamali & Ole Maiava: ‘Mata Makawa – Mata Vou’

Listen to Immaterial to learn what artists’ materials can tell us about art, history, and humanity.

Subscribe wherever you listen to podcasts:

Listen on Apple Podcasts Listen on Spotify Listen on Google Podcasts Listen on Stitcher