Met curator Sarah Graff and history professor Sargon Donabed discuss Assyrian reliefs (ca. 883–859 BCE).

Keeping Culture Alive

Assyrian Relief Panels

Listen to the conversation, learn more about the artworks, and read the transcript below.

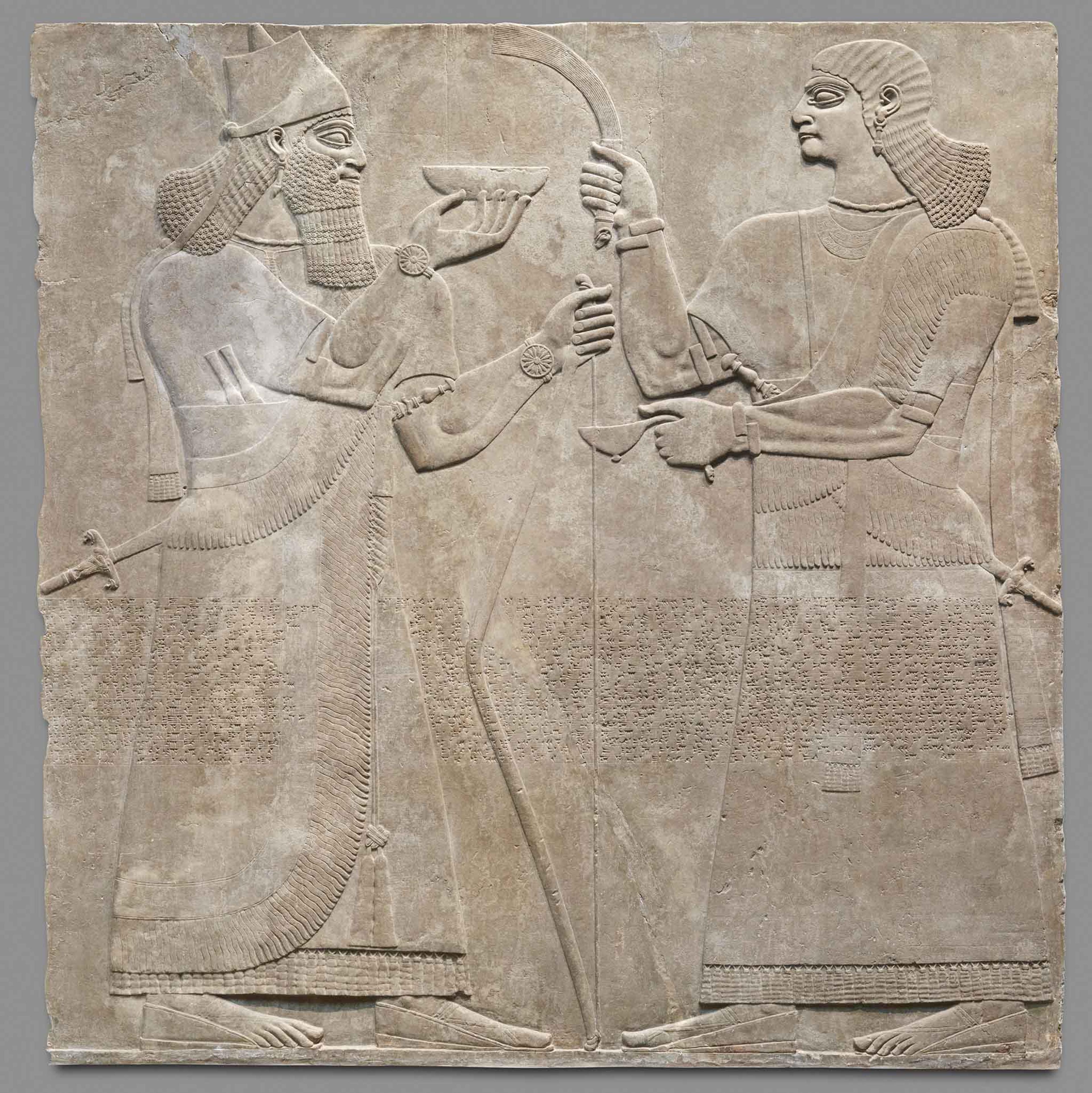

Relief panel, ca. 883–859 BCE. Mesopotamia, Nimrud (ancient Kalhu). Assyrian. Gypsum alabaster, 92 1/4 x 92 x 4 1/2 in. (234.3 x 233.7 x 11.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of John D. Rockefeller Jr., 1932 (32.143.4)

This panel comes from the royal palace of Ashurnasirpal II at Nimrud, then the capital of the Assyrian Empire. The relief depicts a royal attendant and a king, likely Ashurnasirpal himself, but perhaps an ancestral ruler. A second relief to its left features an Apkallu, a supernatural protective figure with the body of a man and the wings of an eagle.

Combining elements of the natural and the supernatural, these panels were intended to reflect the divine right of the king. The cuneiform inscription details the titles and accomplishments of the king as a builder of palaces and a conquerer of people. Thought to serve a magical function, this inscription contributes to the divine protection of both the king and the palace.

Transcript

SARAH GRAFF: My name’s Sarah Graff. I’m an associate curator in the department of ancient near Eastern art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

SARGON DONABED: My name is Sargon Donabed. I am an associate professor of history at Roger Williams University in Rhode Island. And my focus has been on Assyrian culture and heritage, predominantly more the modern period in recent years, although I have studied ancient languages and culture of Mesopotamia.

—

GRAFF: So the reliefs that are on view at The Met in the Assyrian Sculpture Court come from the palace of Ashurnasirpal II at Nimrud, which is near present day Mosul in Iraq. And they come from a palace that was built and decorated in the early ninth century BC.

Most of the figures that you see on the reliefs are figures that we tend to call Apkallu, a body and often the head of a human, large wings of a bird of prey, and then sometimes the head of a bird of prey.

The Apkallu were the kind of seven sages who lived before the flood. So the flood story that is preserved in the Bible is not the oldest flood story. The oldest flood story that we know of comes from ancient Mesopotamia. It’s a similar idea, the gods wiped out all of the humans. And in this time before that first flood, there were seven sages that lived in the land of sweet waters that is the domain of wisdom and of life. And it’s the seven sages who kind of maintain this connection to that primordial world. So they are kind of the connection to the original wisdom of the earth before humans.

It’s an incredibly transporting space. It’s a space that’s been set up along the proportions and the lines of an Assyrian audience hall. But even though it’s very effective at giving that sense of grandeur and space, the reliefs didn’t come from the same rooms for the most part. So they are a pastiche of different rooms that are being put together to give this impression of wholeness.

DONABED: The reliefs in a sense have sort of been dispossessed and then repossessed and reconstructed, in a particular way, much like the Assyrians themselves. The people themselves have been displaced, removed from their land, forced to flee from their region under threat.

As many of these pieces possibly would have been of course in the future, we see 2014 and 2015, the advent of the so-called Islamic State and the destruction, the literal effacing of some of this material from the exact same place in Nimrud.

And it was possible that these pieces themselves would have also been destroyed at that same time. If not completely destroyed, then certainly effaced. In cases where both living community and culture itself have been displaced, have been removed, many times, actually, they parallel each other.

GRAFF: People do often say, ‘Oh, I’m so glad that these Assyrian reliefs are here, that they’re safe.’ But that always kind of sits wrong with me. And I like to correct it by reminding people that art and people are linked. You can’t keep art safe and leave people to the winds.

And similarly, you, you can’t keep people safe and disregard the fate of their art. They have to be addressed together because they are mutually constitutive.

There’s a sign over the entrance to the National Museum of Kabul in Afghanistan that reads: “A nation stays alive when its culture stays alive.” The point being that simply surviving isn’t really enough that you need your culture as well to constitute you as people.

DONABED: Great point. And I think that in the case of these particular reliefs, the extravagance of the palace, the sort of the grandeur of ancient Assyrian royalty and their political culture, that juxtaposition with Assyrians and the modern world the lack of state, lack of recognition, it’s a very interesting sort of dichotomy to wrap our heads around.

Part of that too, though, is when we think, ‘What is art?’ It's an expression of our, our desires, our hopes, our dreams, you know, many cases, sort of the abstract longings that we may have. And I have this moment of being at the British Museum as, as a young boy and having this desire to touch this material because as a young kid, you know, I’d heard about this grandeur of Assyrian art and architecture, but I'd never actually had the option or had the ability to come into contact with it in the British Museum, I remember touching it and saying to my little brother, ‘Oh yeah, these are ours.’

And you know, this is a young kid from Boston who also has this deep Assyrian heritage, which I never could quite express in words, but I understood it when I touched the Lamassu and of course was reprimanded immediately, one of the guards saying, ‘Don’t, don’t touch that.’ And I said, ‘But it’s mine.’

In some senses I should, I should say maybe, perhaps not in all, but in some senses I am dispossessed of this material as an Assyrian. It exists in museums. It exists outside of me in many ways, but that does not stop me from connecting with the material, regardless of where it is, regardless of what portion or part of the world that exists in, in what condition it’s in, whether it’s falling apart, whether it has been reconstructed, that is what this art can offer us.

###