Among the nineteenth-century alkaline-glazed stoneware in the exhibition Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina, there is a grouping of massive, round-shaped jars produced by the literate, enslaved potter and poet Dave (later known as David Drake). Documented by scholars as vessels for food storage and preservation, these jars were central to smokehouses and kitchens on plantations, storing large quantities of food. Their exact contents, however, have remained speculative.

Gallery view of the exhibition Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina. © Metropolitan Museum of Art

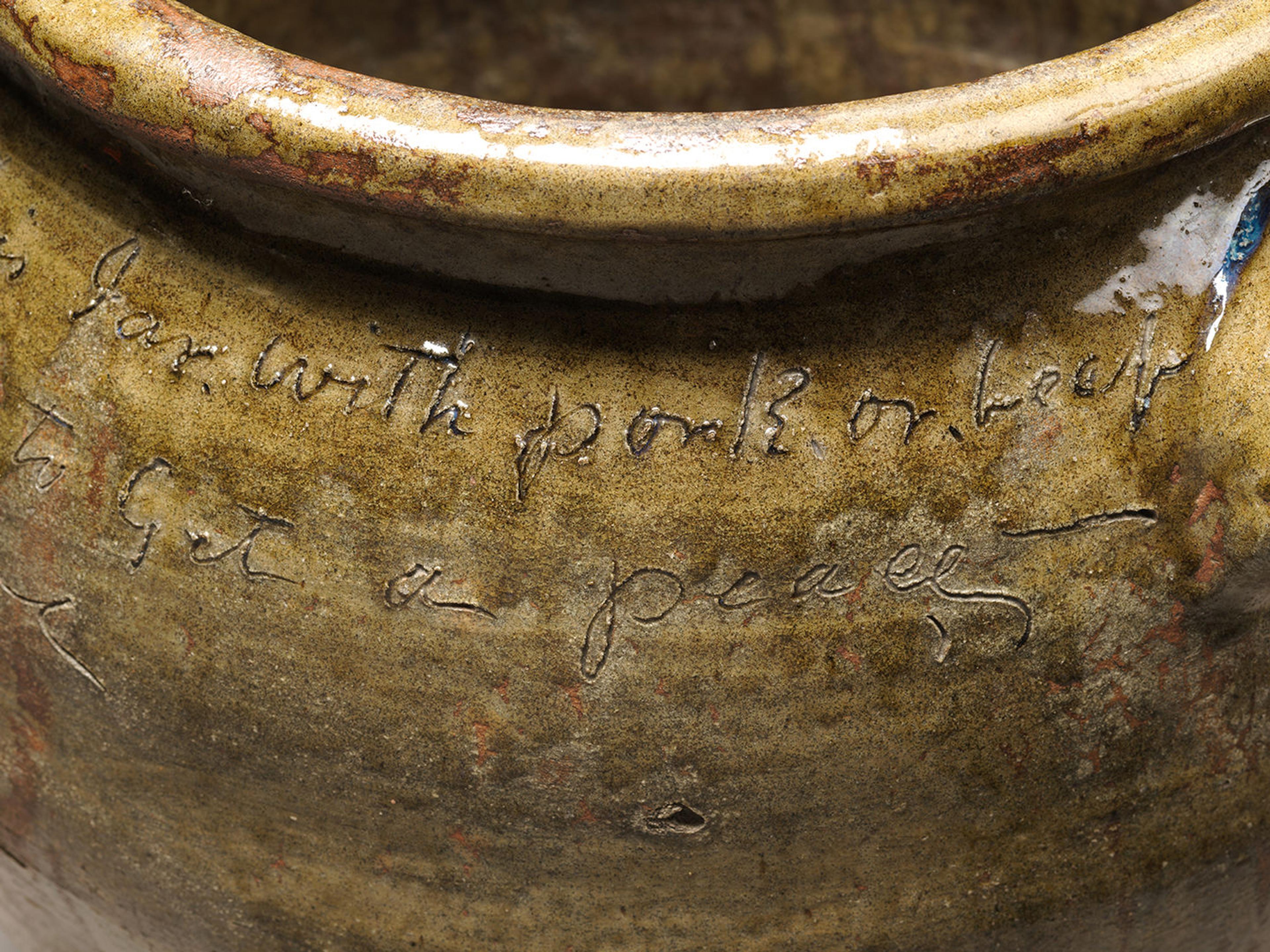

The jars’ function and what they held are referenced in occasional incised inscriptions on their distinctive exteriors, fashioned as verses, along with a date and Dave’s signature. These inscriptions are important clues for context and represent Dave’s agency at a time when literacy was illegal for enslaved persons. The pots were prized for their high quality, and many were later adapted for other purposes until they became valuable collectibles during the second half of the twentieth century.

Listen to the sound of the sticky residues found in the storage jars

The idea to investigate the historic residues found on these jars came during research visits to museum collections in South Carolina, specifically on one humid day at the University of South Carolina’s McKissick Museum. Adrienne Spinozzi, Associate Curator in The American Wing, and a co-curator of the exhibition, smelled something rancid while peeking inside several of the vessels along with colleagues from the McKissick Museum and the curatorial team. With gloves on, they examined one sizable jar, experiencing firsthand the tactile stickiness of the residue under the rim and the sound it made at their touch.

Organic residues on historic glazed pottery are rare. Their permanence depends on how the pots were stored, and their treatment after they stopped being used as functional objects—specifically, whether they were cleaned, repurposed, or discarded. Given later interest in collecting these particular vessels, others were intentionally cleaned to remove any sticky or odiferous traces of contents. Because of this, it makes any discernable residues even more fascinating and valuable to study.

During the fall of 2019, The Met’s conservation, scientific research, and curatorial staff traveled to South Carolina and collected several samples from Edgefield jars that still contained layers of sticky residue. One jar entered the collection of the McKissick Museum in the early twentieth century—and thus had not been thoroughly cleaned—and another that had been passed down from the family of the original owner. Both are large storage jars that feature poems dated and signed “Dave.”

Left: Distribution of the organic residues on the exterior of David Drake’s jar under ultraviolet illumination. Photo by Kate Hughes. Right: Adriana Rizzo sampling organic residues inside the same jar. Photo by Kate Hughes

At first glance, we observed sticky, viscous residues in the recessed areas on the interior and exterior walls of the jars. Under the ultraviolet radiation of a portable UV LED flashlight, we could identify the distribution more clearly because the accumulation pattern on the surface showed as a distinctive bluish fluorescence on the glazed surface. Although less brightly fluorescent, drier, gooey crusts were evident in the lower parts and bottoms of the vessels. Our team wore gloves and, with my guidance, carefully scraped surface residues for analysis—their arms deep in the jars and equipped with micro-scalpels.

Left: Detail of organic residues on the exterior of David Drake’s jar at the McKissick museum. Photo by Kate Hughes. Right: Detail of the accumulation of black residues under the ear-like handles of a Drake jar in a private collection. Photo by Adriana Rizzo

On one jar, layers of thick, gummy residues and black deposits had accumulated under the ear-shaped handles, as might be expected after years of use in smokehouses. We sampled these and found different degrees and sizes of black particles in the residues, which likely attest to the jar’s proximity to fire. Historically, while the massive size and weight of the jars made it difficult to clean them between uses, it allowed residues to accumulate on the jars’ surfaces.

Left: Christian Cicimurri, Curator of Collections at the McKissick Museum, University of South Carolina, overseeing analysis with the portable FTIR (p-FTIR) with the external reflectance (ER) module, on the exterior of the McKissick Museum’s Drake jar. Photo by Kate Hughes. Right: Adrienne Spinozzi and Katherine Hughes, Curator of Cultural Heritage & Community Engagement, McKissick Museum, University of South Carolina, (at the time Peggy N. Gerry Research Scholar in The Met’s American Wing) analyzing organic residues by p-FTIR with the attenuated total reflectance (ATR) module, at the McKissick Museum. Photo by Adriana Rizzo

Conservative collecting practices, which prioritized preserving evidence of use over thorough cleaning, have also been critical for the survival of the organic residues, enabling our research. Analysis undertaken at the McKissick Museum by portable Fourier-transform infrared (p-FTIR) spectroscopy helped assess the type of residues, as composed mostly of lipids from oils and fats. This information aided us in determining the sample size needed for our laboratory to do further analysis.

Back in The Met’s laboratory, we photographed and analyzed the residues, first with the FTIR microscope and then by separation techniques of gas-chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC-MS). As expected, we detected lipids attributable to fats, meat products, and oils in all residues. Profiles and distribution of fatty acids indicated varying degrees of oxidation and hydrolysis from aging in the presence of air and moisture. A few samples showed the possibility of protein in the residues as well.

Dave (later recorded as David Drake) (American, ca. 1801–1870s). Storage jar (detail of inscription reading “jar with pork or beef”), 1858. Alkaline-glazed stoneware, Height: 22 5/8 in. (57.5 cm); diameter: 27 in. (68.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Ronald S. Kane Bequest, in memory of Berry B. Tracy, 2020 (2020.7)

Discerning the animal species through the lipids or proteins from the animals stored in the stoneware is only achievable with sophisticated analytical techniques. This type of specialized research is possible thanks to The Met’s collaboration through ARCHE (Art and Cultural Heritage: Natural Organic Polymers in Mass Spectrometry) with the University of Bordeaux, France. They are investigating trace amounts of proteins in the oily residues from the jars and attempting to assign them to specific tissues and animal species. Our goal is to positively identify the contents of the jars and connect them to Dave’s inscriptions that allude to pork, beef, sheep, goat, and bear (possibly a misspelling of boar).

Historical recipes mention the use of stone jars, earthenware, and crocks for preserving meat—mainly beef, pork, and mutton—along with animal fats, also including lard and butter as toppers. Stoneware jars were additionally used in storing butter for winter between layers of salt, and for preserving chopped suet, or beef fat, in molasses for year-round consumption. For dry curing, meat would be layered with mixtures of salt and saltpeter, sometimes with the addition of sugar, molasses, and spices, prior to smoking. In warm weather, preserving meat in brines was the preferred method and required less expertise than dry salting. Our replication in the lab of curing and pickling meat using historical recipes made it clear that these large-scale preservation methods were time-consuming and required skill and accountability.

Dave (later recorded as David Drake) (American, ca. 1801–1870s), Storage jar, 1857. Alkaline-glazed stoneware, Height: 19 in. (48.3 cm). McKissick Museum, University of South Carolina, Columbia, Donated by Belle Williams in memory of Admiral Yancy S. Williams. Photo by Eileen Travell

Beyond the scope of identifying what was stored in these jars, our research highlighted the substantial anthropological value of the residues. The appearance, position, and occurrence of residues in the jars helps us understand the vessels’ histories and interpret how they were used. Although we might never know the identity of those who used the jars and the specific recipes they prepared at a given time, the presence of these residues is an integral part of the story. Our research inextricably connects these objects to the time when their existence and contents were central to the lives of those whose sustenance was stored inside, which included the enslaved population. These surviving vessels and their residues, accompanied by Dave’s verses that reveal their purpose, contribute to our understanding and appreciation of them today.