A serpent is their protector; a tree is their refuge. A young man and woman look out toward their viewers, her hand resting casually on his shoulders. She is relaxed, her other hand on her hip. They don’t wear much besides heavy gold jewelry. His hair is matted like the thick vines of a tree; hers like the coils of a serpent. Vines grow on their limbs. The natural world exists both within them and around them. Their image is rendered in the browns and grays of ancient stones—created around the time of the Buddha, between 200 BCE and 400 CE. They are like the Instagrammers of their times, using images to spread their vision of an ideal world where all living beings coexist in harmony.

Ayaka cornice with four narrative roundels [Detail]. Ikshvaku, late 3rd century CE. India, Nagarjunakonda, Gunter District, Andhra Pradesh. Limestone. H. 22 1/6 in. (56 cm); W. 100 13/16 in. (256 cm); D. 8 1/4 in. (21 cm). Lent by the Archaeological Museum ASI, Nagarjunakonda, Andhra Pradesh. Copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Thierry Ollivier.

The Buddha began life as a young prince, Gautama Siddhartha, living a sheltered existence in his palace with most worldly desires fulfilled. Aching for meaning and purpose, he abandoned his riches in search of a truer world where humans and nature remain in balance, each serving as a metaphor for the other’s strengths. In this world, reliquaries reign over kingdoms, poetry is a means for a polity, and images depict humans and nature as one, inseparable from each other. It’s a world of augmented realism, where the architecture exudes the sweet fragrance of sandalwood, trees bestow jewelry along with flowers, footsteps are personified and revered, elephants are devout—cleansing deities with water from rivers—and serpents are gentle enough to cradle infants.

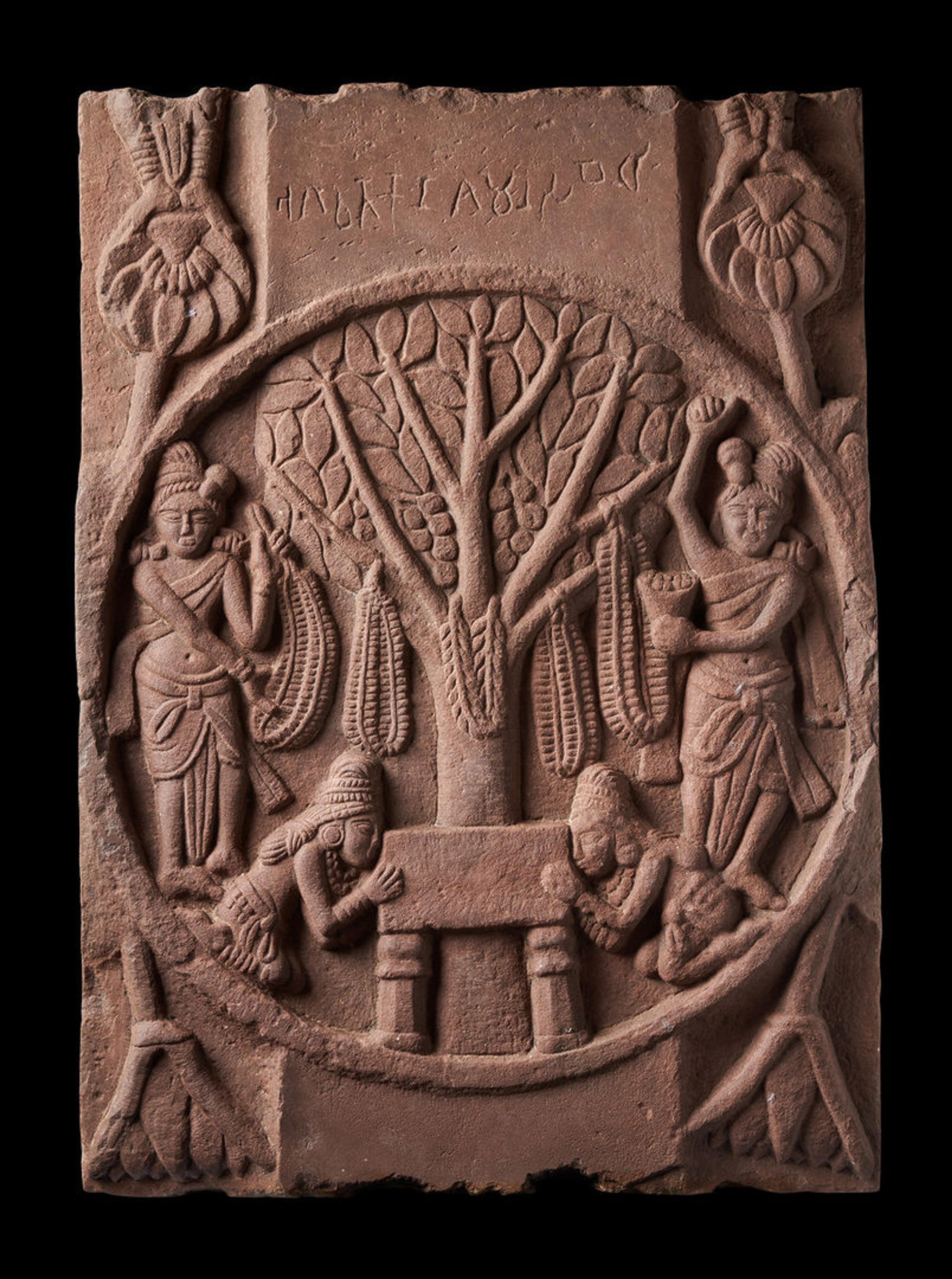

Railing pillar medallion: tree shrine marking Konāgamana Buddha's awakening. Shunga, ca. 150–100 BCE. India, Bharhut Great Stupa, Madhya Pradesh. Sandstone. Overall: H. 27 15/16 in. (71 cm); W. 20 1/16 in. (51 cm); D. 6 11/16 in. (17 cm). Lent by the Indian Museum, Kolkata. Copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Thierry Ollivier.

In this ancient landscape, far removed from our world today, the Buddha developed his ideals. Paradoxically, these same ideals offer solutions to our most urgent and modern problems. This ancient world enables us to think more deeply about our engagement with this planet and its resources; it provides examples of symbiotic relationships between living creatures and their environment, in which all participants have equal agency and equally benefit from the success of their efforts. These Buddhist teachings offer a way to address our most pressing climate concerns.

Dharmachakra. Kushana, ca. 200 CE. India, Chausa, Shahabad district, Bihar. Copper alloy. H. (incl. shaft) 12 3/4 in. (32.4 cm); W. 7 3/4 in. (19.7 cm); D. 1 3/8 in. (3.5 cm); Diam. 8 in. (20.3 cm. Lent by the Bihar Museum, Patna. Copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Thierry Ollivier.

These ideals are a world of dharma, signified by the wheel (chakra), where the natural laws of the universe are respected as truths, and therefore our forests and oceans are to be protected rather than exploited for short-term gains; a world of sangha, where communities of like-minded individuals come together around a common cause, such as safeguarding our climate; a world of sambhandhan, where interconnectedness is an imperative that drives climate diplomacy among nations and other groups; a world of smriti, where each individual is mindful of their own actions and how they affect the environment; and a world of ahimsa, where nonviolence and compassion play key roles, so that those with the least power, whether humans or animals, are respected and factored into the solutions.

Gateway architrave with makara. Shunga, ca. 150–100 BCE. India, Bharhut Great Stupa, Satna district, Madhya Pradesh. Sandstone. H. 16 1/8 in. (41 cm); W. 25 3/16 in. (64 cm); D. 11 in. (28 cm). Lent by the Indian Museum, Kolkata. Copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Thierry Ollivier.

Since its inception, Buddhism has maintained a strong storytelling tradition as a means of spreading ethics and ideals in the creation of a more compassionate world. These stories, known as Jatakas, describe the previous lives of the Buddha and his encounters with moral conundrums, but they are unique because they do not proselytize set values. They are tales of hyperbole and superlatives meant to spark introspection and conversation. The protagonists are often real and mythical beasts bearing human traits and facing human challenges. Since antiquity, these tales have been recounted orally, through texts and inscriptions, and through visual narrative depictions on architecture. They are simple tales that elucidate deeper values and bring alive the struggles and possibilities of structuring a society that is in harmony with nature.

Drum panel with Naga Muchalinda. Sada. 1st century BCE-1st century CE. India, Dhulikatta Stupa, Karimnagar District, Telangana. Limestone. H. 60 1/4 in. (153 cm); W. 45 1/4 in. (115 cm); D. 8 1/4 in. (21 cm). Lent by the Karimnagar Archaeology Museum, Karimnagar, Telangana. Copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Thierry Ollivier.

Two well-known Jataka stories reveal different approaches to these environmental virtues. The first is the simple story of a stubborn tortoise who lived in a river near a vast ocean. The river was separated from the ocean by a fertile patch of land that yielded clay, which local potters would collect for their craft. After every monsoon, the river and ocean would merge, and the patch of land would be submerged, but with every passing year, as the potters increased, the river slowly dwindled. One year, the nagas (serpentine creatures) that inhabited the river sensed an impending delay in the monsoon, and they warned all the aquatic creatures to travel from the river into the ocean. The tortoise, however, refused to move, as he was very much attached to his home. As the water disappeared, he remained down on the riverbed, taking refuge in his shell until the river was completely dry, and the potters who came to collect the clay broke his shell and scooped him up with soft clay.

At first this story seems to be a straightforward lesson about obstinance, misjudgment, and overattachment, but the story also foretells the disastrous consequences of overconsumption and the impact of changing weather. The tortoise’s obstinance reminds us of the paradox that we are both the perpetrators and victims of climate change.

Pillar abacus: elephants venerating the Rāmagrāma stupa [Detail]. Satavahana, late 1st century CE. India, Amaravati Great Stupa, Guntur district, Andhra Pradesh. Limestone. H. 12 13/16 in. (32.5 cm); W. 25 3/4 in. (68 cm); D. 16 9/16 in. (42 cm). Display module with collar: H. 22 1/2 in. (54 cm); W. 33 1/4 in. (84.5 in.) D. 21 1/3 in. (54 cm). Lent by the British Museum, London. © The Trustees of the British Museum

Another favorite Jataka story regularly depicted in Buddhist art tells the story of the formidable Bodhisattva in the form of a white elephant, Chaddantta, who had six tusks that each emitted divine light. Elephants are particularly revered in Buddhist lore, as they are seen to embody both wisdom and compassion. Chaddantta was so wise that he led a herd of eight thousand elephants. Once, while he was crossing the forest with his two consorts, his crown scraped a flowering forest tree. His favored consort was showered with fragrant petals, while the other was covered with twigs and dried leaves. The humiliated consort vowed to take revenge and undertook dharmic duties that enabled her to be reborn as a powerful queen. As a queen, she ordered a hunter to slay the elephant Chaddantta and bring her his tusks as a trophy. The hunter, awed by Chaddantta’s greatness, was unable to slay the elephant, and Chaddantta, out of compassion for the hunter’s dilemma, with great pain, sawed off his own tusks so that they could be delivered to the queen.

This is a story of self-sacrifice and empathy, but it could also be interpreted on a more pragmatic level as the need to avoid ego and favoritism—the imperative to demonstrate your values in practice and to treat all with respect and equanimity, especially in bringing others along toward a common goal.

Railing pillar fragment: flowering vase of plenty. Shungaca. 150–100 BCE. India, Bharhut Great Stupa, Satna district, Madhya Pradesh. Sandstone. Dimensions: H. 20 1/2 in. (52 cm); W. 13 3/4 in. (35 cm); D. 6 11/16 in. (17 cm). Lent by the Allahabad Museum, Prayagraj, Uttar Pradesh. Copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Thierry Ollivier.

There are about 550 Jataka stories that depict elaborate worlds of spirits, humans, animals, and mythical creatures within a natural environment of rivers, forests, and oceans in consonance with one another. This world is of the ancient past, where the natural and supernatural seem to coexist, and all creatures move seamlessly from one realm to the other. But it is also the world of the Buddha’s teachings, which offer messages for a future where all living beings are treated with respect and value, and humans come together to find ideas to solve some of the greatest crises affecting this planet.