After surviving a near-fatal bullet wound to the shoulder while serving in World War I, Horace Pippin lost partial use of his dominant right arm. He returned home as a disabled African American veteran to a culture that stigmatized disability and was marred by racism. While much of the discourse around Pippin’s work has focused on his identity as a Black veteran and untrained artist, less has been said about the profound effect of disability on his art, a consequence of longstanding biases in art history against bodies that deviate from the construct of the ideal form.[1] Pippin's unlikely rise as a canonical American artist during the early twentieth century is a testament to his exceptional creativity, tenacity, and ability to leverage social networks to advance his career.

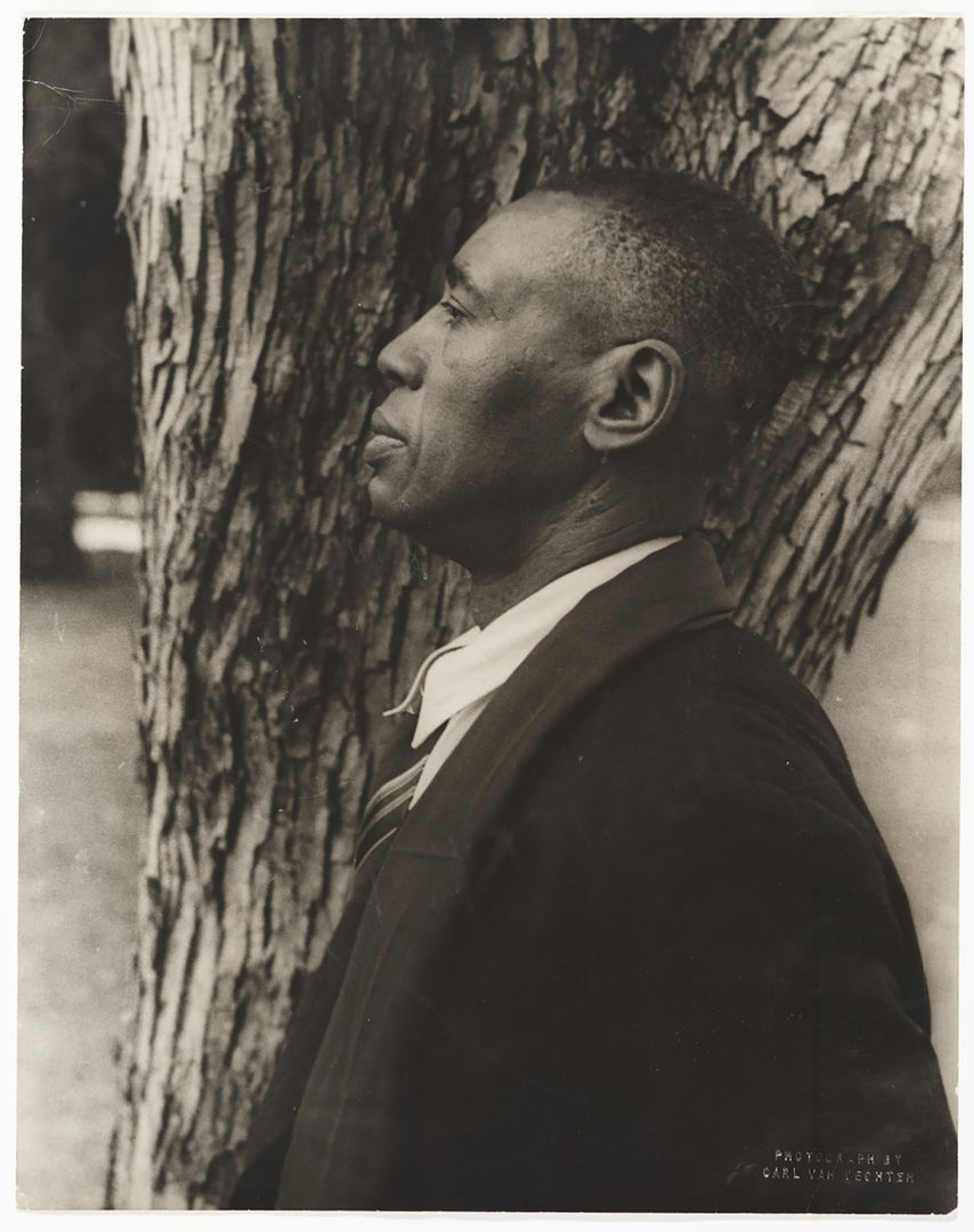

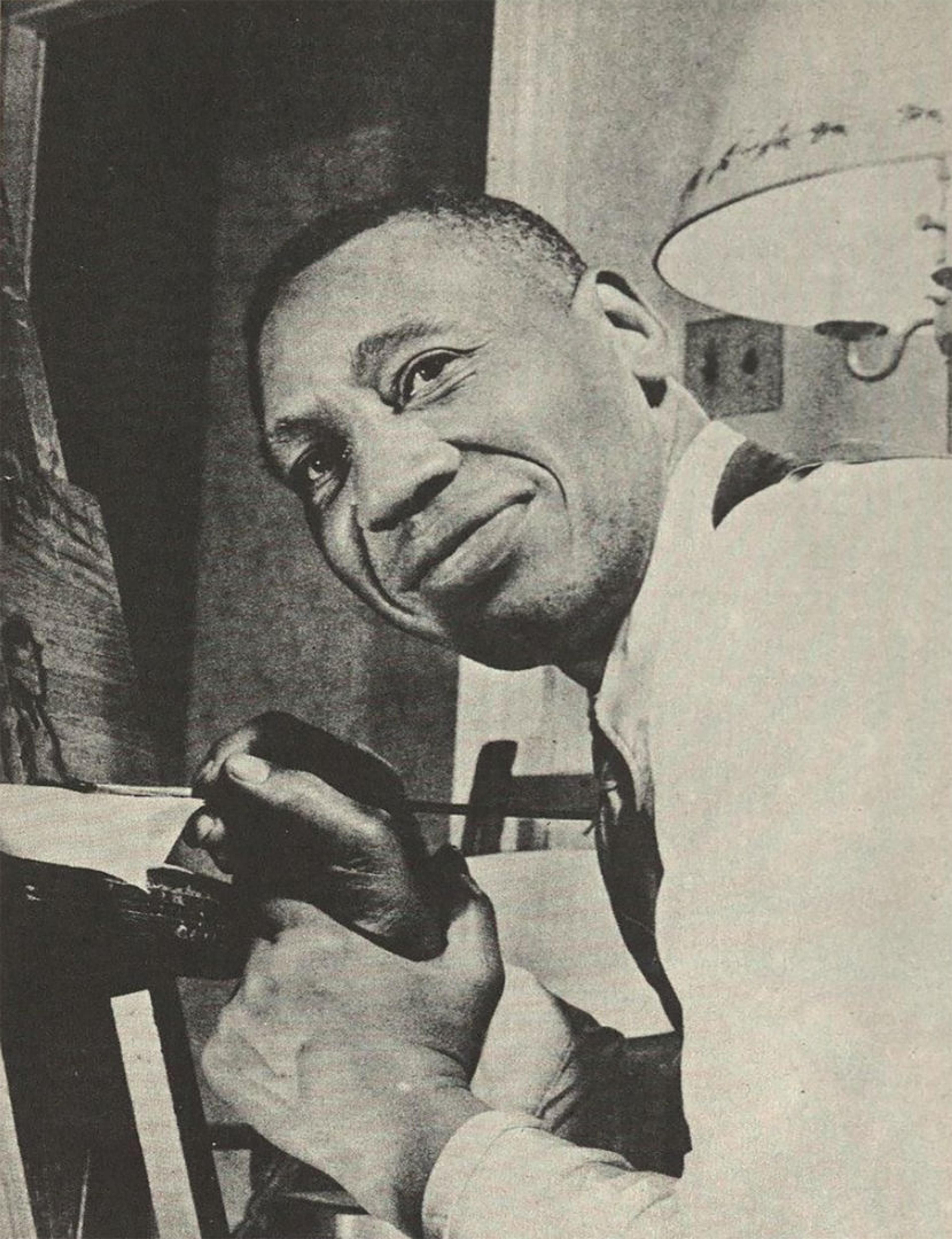

Carl Van Vechten. Horace Pippin, 1940. Downtown Gallery records, 1824–1974. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

In 1917, at the age of twenty-nine, Pippin enlisted in the U.S. Army, where he was assigned to the 369th Infantry Regiment, an all-Black group of soldiers.[2] During the war, due to racist segregation policies, Black recruits were used as laborers rather than as fighters. Once Pippin’s regiment got to France in 1918, however, extra support was desperately needed to provide aid against the German offensive, and the 369th Infantry Regiment was attached to French divisions.[3] The group saw intense combat and became one of the war’s most famous and courageous U.S. regiments, the Harlem Hellfighters. Pippin wrote a vivid account of his service in a sixty-one-page journal containing numerous battlefield illustrations.

These writings provide a detailed account of Pippin’s life-altering injury. When Pippin and his comrade were pinned down in a shell hole by surrounding machine guns and snipers, the two attempted to flank a German soldier. As Pippin moved to another shell hole, a bullet struck him: “I got near the shell hole that I had packed out when he let me have it. I went down in the shell hole. He clipped my neck and got me throu my shoulder and right arm.”[4] Pippin attempted to plug the wound while his friend took out the German gun before returning to help.

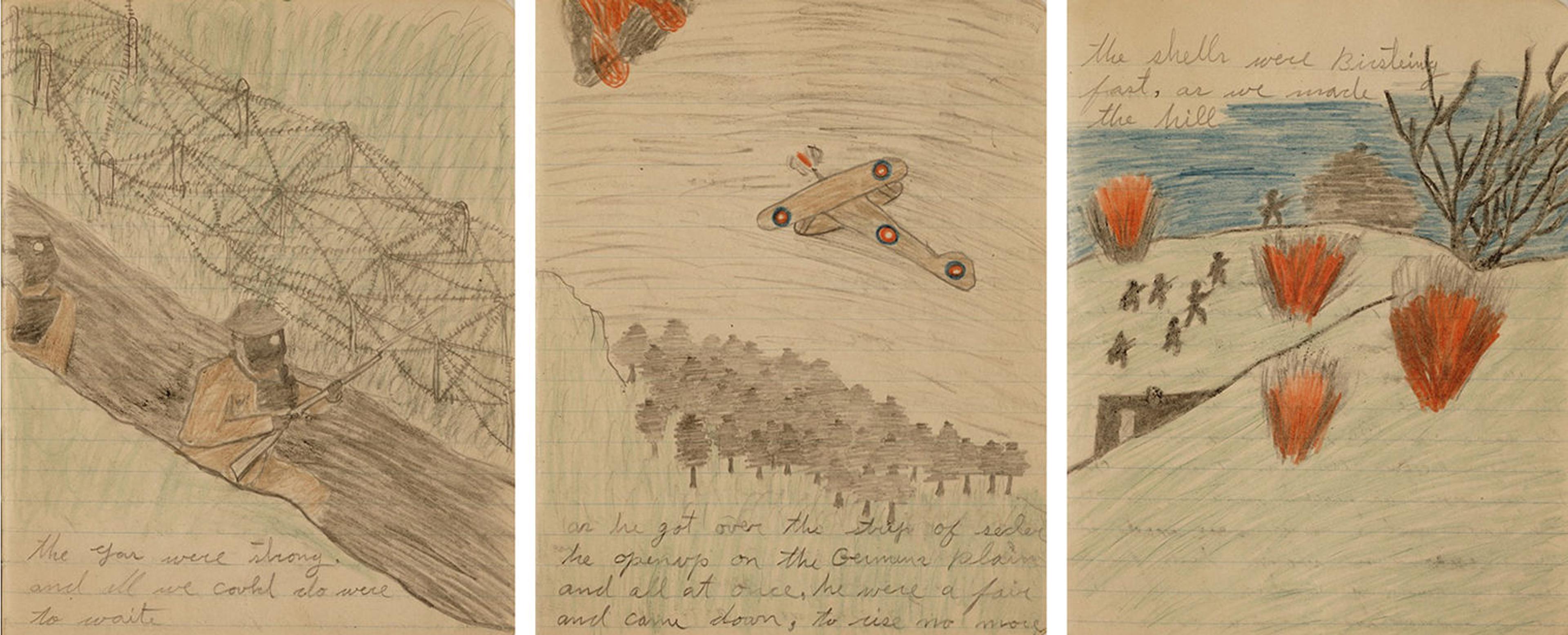

Three illustrations from Pippin’s War Memoirs. Courtesy of Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

According to his journal, Pippin lay in the trench, too weak to move. At one point a French soldier came to help him but was shot in the head, fell on top of him, and Pippin could not remove the body due to exhaustion. Eventually Pippin was recovered and given medical attention. There are also clear manifestations of Pippin’s war trauma in the journal drawings. The colored pencil illustrations present vivid images of combat: men in gas masks walking in trenches beside barbed wire; explosions on the battlefield as soldiers run across no man’s land, fighting for their lives; and a U.S. plane firing ammunition above a forest. More than just a recollection of events, Pippin’s journal strikingly captures a horrific incident that left him with a physical disability for the rest of his life.

In 1919, after the war concluded, Pippin came home with a steel plate connecting his crippled right arm to his shoulder. He was given a disability pension of $22.50 per month, which would be approximately $400 today.[5] Soldiers with disabilities were encouraged to become “successful cripples” through rehabilitation and reintegration into society, improving the treatment of physically impaired veterans in America.[6] African Americans with wartime disabilities, however, encountered worse social and employment barriers.[7] Despite marrying and becoming part of his community—achieving, in many ways, a heteronormative model of success while living with a disability—Pippin likely still faced discrimination. Racism and ableism have been deeply intertwined in America at least since the nineteenth century, when disability in African Americans was used to justify slavery and white supremacy.[8] Furthermore, Black veterans returning from the war still faced acts of violence and prejudice despite their contributions to the war effort.[9]

Working against these oppressive structures, Pippin began producing wood-burnt panels as a form of physical therapy, eventually buying oil paint, and, with no formal training, rendered subjects ranging from biblical scenes to domestic interiors. Around this critical period of growth in Pippin’s popularity, the artist painted his first Self-Portrait (1941).

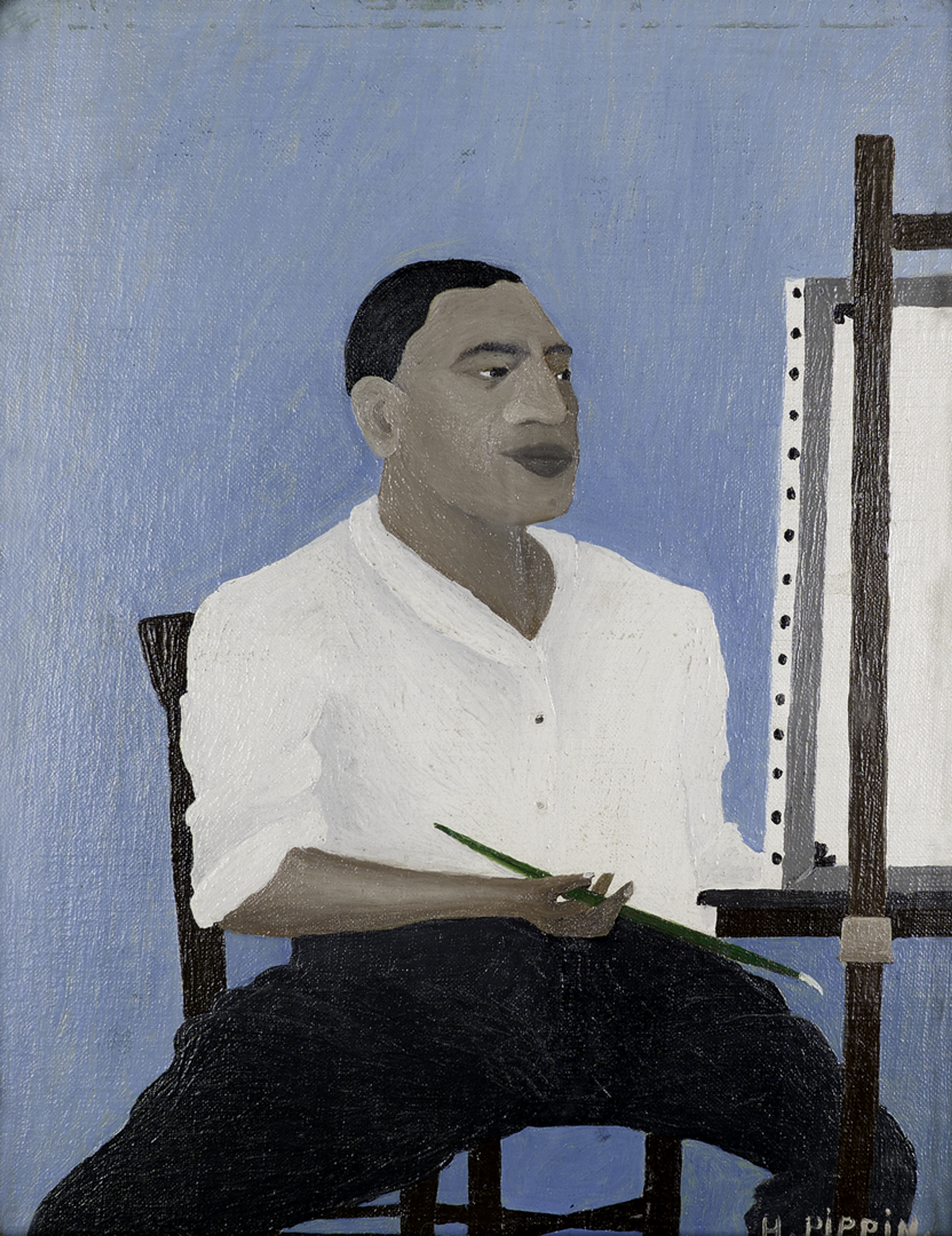

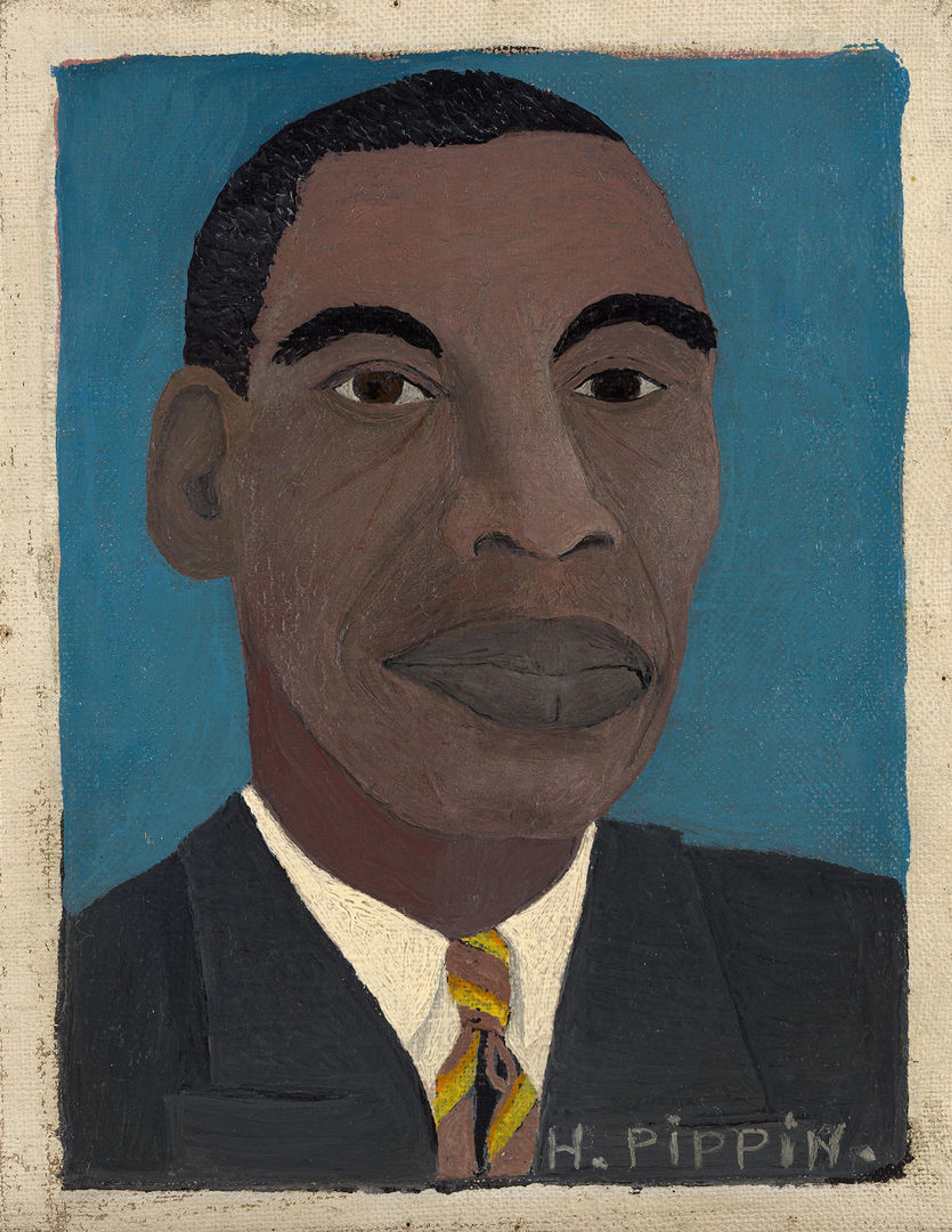

Horace Pippin (American, 1888–1946). Self-Portrait, 1941. Oil on Canvas Board. 19 x 8 x 9" 14 x 11 inches (35.56 x 27.94 cm). Collection Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York Room of Contemporary Art Fund, 1942 RCA1942:2

In the self-portrait, Pippin sits before a nondescript light blue background with his legs casually spread, wearing a white shirt and looking at his stretched canvas on an easel. Pippin’s injured right arm looks atrophied, disproportionately small compared to his body, and rests on his thigh, a long green paintbrush gripped in his hand, which the scholar Anne Monahan has written “points to art making’s regenerative role in transcending that physical and psychic damage.”[10] The composition of the arm makes it the focal point, taking up the lower third of the painting. Pippin further draws attention to this detail by rolling up his white sleeve, exposing the entirety of his forearm with his skin painted in a light brown that creates a contrast against his white and black clothing. The placement of the arm on top of his thigh indicates a moment to rest his injured right arm.

Photograph taken from Selden Rodman’s Horace Pippin: A Negro Painter in America (1947)

In a photograph from Selden Rodman’s Horace Pippin: A Negro Painter in America (1947), Pippin is shown supporting his injured right arm from the wrist with his left while painting. Pippin’s first self-portrait gives a vivid and open expression of this permanent wound, and knowing his biography, we can grasp Pippin’s status as a disabled veteran. Painting with an impairment itself is also a disabled act of creativity—working with tools intended for an abled-bodied society using innovative means that allowed for self-determined artistic expression. Self-Portrait radically celebrates the value of physical difference both in what it portrays and through the method of its creation, standing in direct opposition to the exclusionary trope of the perfect body and artist, which has historically marginalized those with physical and mental differences in Western culture. Pippin’s work indicates a more significant shift where modernist artists embraced disabled bodies as beautiful; however, there is still resistance to totally accepting these aesthetics from contemporary audiences.[11]

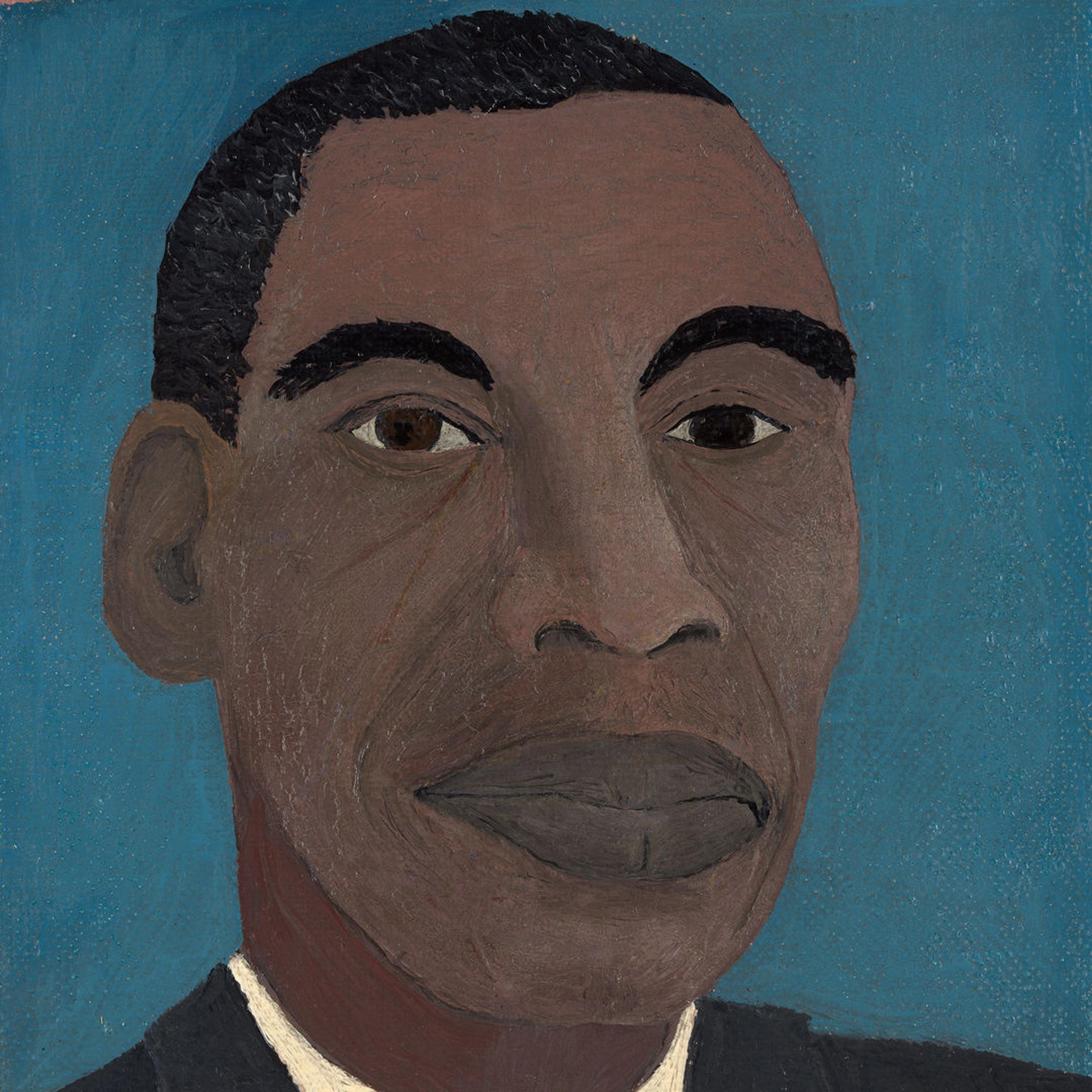

Horace Pippin (American, 1888–1946). Self-Portrait II, 1944. Oil on canvas, adhered to cardboard. 8 1/2 × 6 1/2 in. (21.6 × 16.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Jane Kendall Gingrich, 1982 (1982.55.7)

Examining Pippin’s postcard-sized Self-Portrait II (1944), possibly a gift from Pippin to the wealthy socialite Jane Hamilton, one would never know the history of his embodiment as a wounded veteran. The painting depicts Pippin from above the shoulders, wearing a brown suit and striped tie, looking outward with a distinguished, calm gaze. Pippin’s decision not to display his injury here also may speak to historical trends where disabled individuals chose to conceal physical difference and present as non-disabled.

Regardless, this aspect of Pippin’s identity is an inexorable part of his life and creative process, and critical to understanding his choices when representing himself. Although exploring histories of oppression is often difficult, acknowledging these narratives can open up new readings of an artist’s life and work. By uplifting analysis that reconsiders and weaves in the role of disability in art, we not only better understand the history of an object and its maker, but also take a step toward destigmatizing and valuing difference in museum collections.

Notes

[1] For recent scholarship that strongly considers Pippin’s disability see Suffering and Sunset: World War I in the Art and Life of Horace Pippin (2015) by Celeste-Marie Bernier, Horace Pippin, American Modern (2020) by Anne Monahan, and Lauren Kroiz's lecture Horace Pippin: Burnt Wood (2015).

[2] Selden Rodman and Carole Cleaver, Horace Pippin: The Artist as a Black American (Garden City, NY: Double Day & Company, Inc., 1972), 36–37.

[3] Ibid, 40.

[4] Horace Pippin, Horace Pippin memoir of his experiences in World War I, ca. 1921. Horace Pippin notebooks and letters, circa 1920. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

[5] Rodman and Cleaver, Horace Pippin, 56.

[6] Kim E. Nielsen, A Disability History of the United States (Boston, MA: Beacon Press 2012), 129.

[7] Ibid, 129.

[8] Douglas C. Baynton, “Disability and the Justification of Inequality in American History,” in The Disability Studies Reader, edited by Lennard J. Davis (New York: Routledge, 2013), 23.

[9] Puchner, Edward. “Winning The Peace Over Mr. Prejudice,” in Horace Pippin: The Way I See It, ed. Audrey Lewis (London; New York: Scala Arts Publishers Inc., 2015), 57.

[10] Anne Monahan Horace Pippin, American Modern. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2020.), 1.

[11] Tobin Siebers, Disability Aesthetics (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2013), 19.