The Neolithic and Early Cycladic figures of nude women with arms folded across their abdomens sculpted in the Greek islands at the center of the Aegean Sea represent a unique culture that flourished from around 5300 to 2000 BCE and suddenly disappeared. The later Greeks called these islands Cycladic, from the Greek kyklos (circle), as they encircle Delos, the sacred birthplace of the Olympian twins Artemis, goddess of nature, fertility, and childbirth, and Apollo, god of music, medicine, and the sun. Who were these prehistoric white marble figures, and what did their characteristic pose signify?

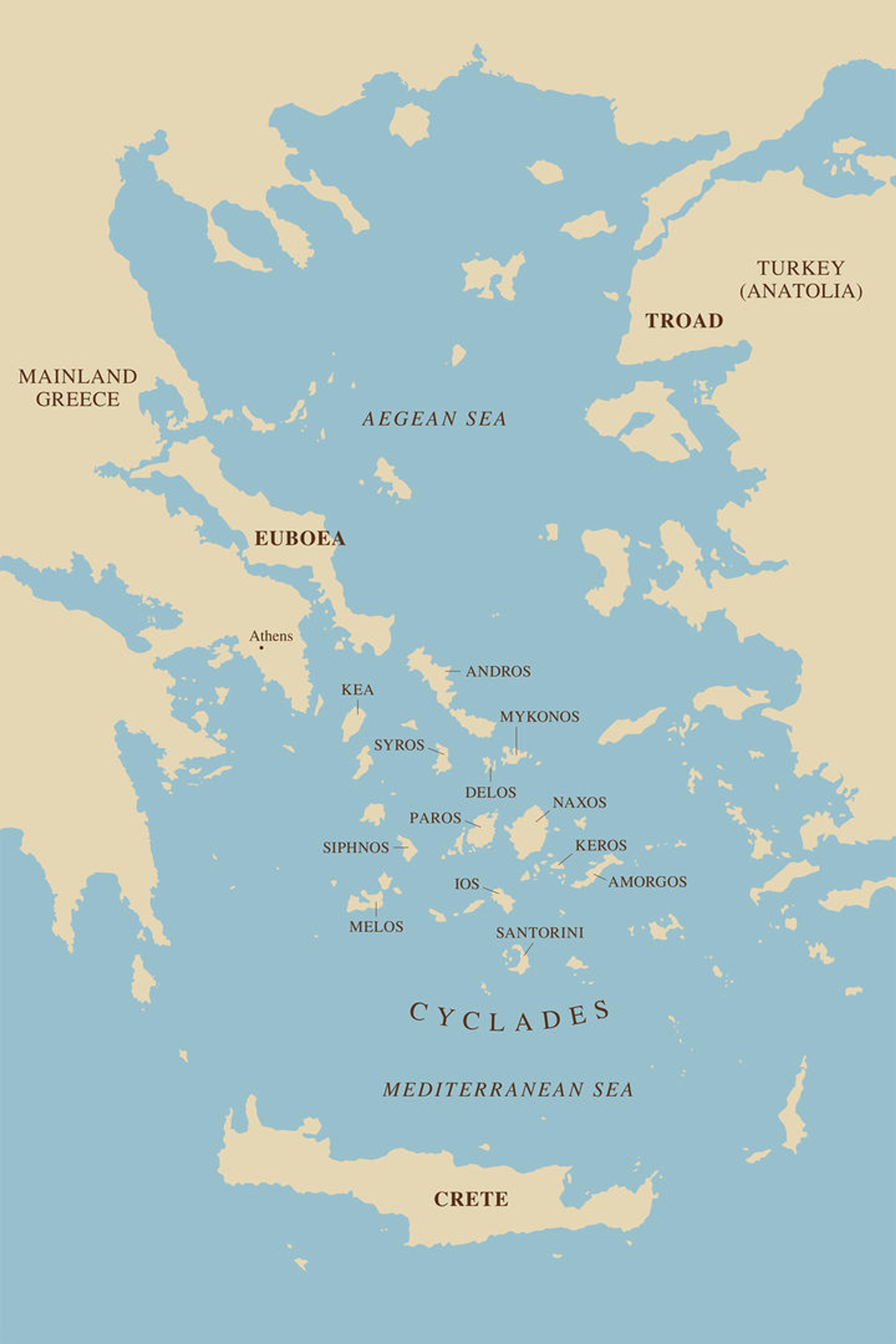

Map of the Cycladic Islands

The meaning of these figures has eluded archaeologists since their rediscovery nearly two centuries ago, following the modern Greek state’s establishment in 1830. Travelers from across Europe rushed to explore the newly formed country, looking for vestiges of a glorious past they had only read about in ancient texts. Athenian historian Thucydides, in the fifth century BCE, reports that when King Minos of Knossos had extended his thalassocracy, or rule of the sea, from Crete into the Cyclades, he expelled the Carian pirates of Asia Minor who had settled there.[1] So when the first modern travelers saw graves and artifacts that were clearly pre-Greek, they attributed them to these Carians, whose homeland was in southwest Anatolia, modern Turkey.

Marble female figure, ca. 2500–2400/2300 BCE. Early Cycladic II. Marble, 5 3/8 × 21 1/8 in. (13.6 × 53.7 cm). Leonard N. Stern Collection, Loan from the Hellenic Republic, Ministry of Culture (L.2022.38.47)

These travelers began to acquire the marble figures and plain vessels found with them, regarding the former as crude works reminiscent of Egyptian mummies with their arms folded over their abdomens.[2] The first example, donated to the French National Library in 1859, was inventoried as a “primitive Venus,”[3] as only the Greek fertility goddess Aphrodite, or Venus to the Romans, was portrayed naked. By the close of the nineteenth century, they were widely compared to the prehistoric predecessor to fertility goddess Artemis of Ephesus in southwest Anatolia, who exposes her breasts to provide an “inexhaustible fountain of nourishing milk.”[4]

Early-twentieth-century archaeologists dismissed the goddess theory with more mundane explanations such as eternal substitutes for concubines or the enslaved who were sacrificed to accompany their masters in the afterlife. Other suggestions include children’s toys, as most are the size of modern handheld dolls; images of venerated ancestors; or apotropaic images of men and women designed to protect their owners from evil after death.[5] These explanations fail to account for the variety of images and the fact that they were often eroded, repainted, repaired, and found in settlements and not exclusively in funerary contexts.

The poet Robert Graves helped revive the goddess theory in 1948 with The White Goddess, his popular and influential study of the mythical origins of poetry, which focuses on humanity’s hypothesized earliest deity: the Goddess of Birth, Love, and Death.[6] Many societies in tune with nature perceive a sky god who fertilizes a primal earth goddess to bring forth the natural world and helps to nourish her until the end of each year when all things return to the ground only to re-emerge in a never-ending life cycle linked to the sun. This fundamental life-bearing goddess appears under countless names across ancient societies, from the Sumerian Kishar, who becomes Akkadian Ishtar and Babylonian Astarte, to Hathor in ancient Egypt.

Left: Venus of Willendorf, c. 24,000–22,000 BCE. Limestone, 11.1 cm high Naturhistorisches Museum, Vienna (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0). Right: Marble female figure, ca. 5300–3200 BCE. Late Neolithic, Cycladic. 2 15/16 × 5 15/16 in. Marble (7.4 × 15.1 cm). Leonard N. Stern Collection, Loan from the Hellenic Republic, Ministry of Culture (L.2022.38.131)

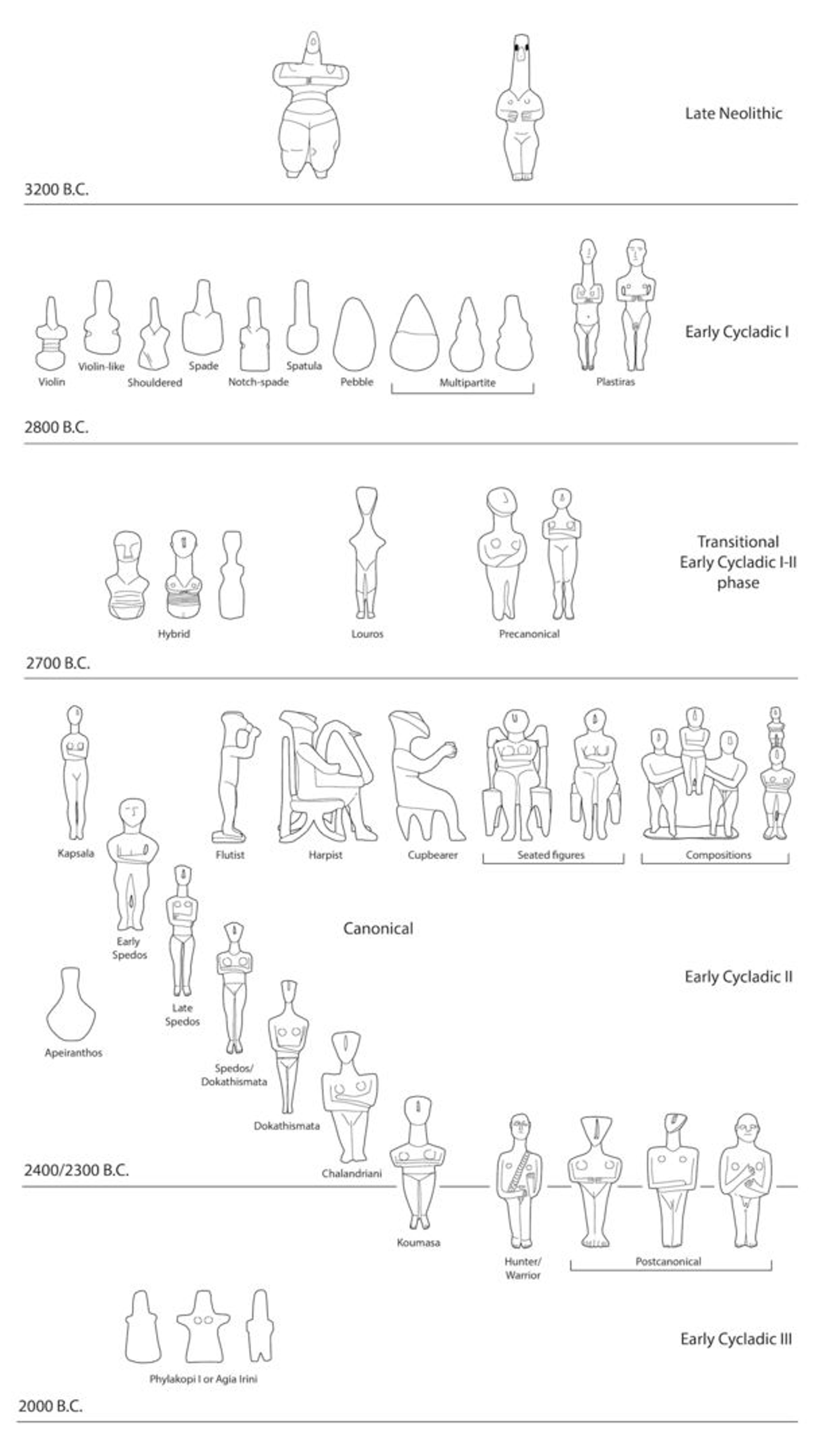

The Early Cycladic female figures with exposed breasts and genitalia became candidates for the life-giving goddess herself,[7] but their purpose is likely much more complex. The earliest figures sculpted in the Neolithic period represent standing or seated cross-legged bountiful female forms that resemble the first images of women to survive from the European Paleolithic, like the famous Venus of Willendorf (24,000–22,000 BCE). With the start of the Bronze Age around 3200 BCE, the islanders produced increasing numbers of these figures, which, through the next millennium, transitioned from abstract pebbles and schematic forms to more naturalistic anthropomorphic sculptures before returning to abstraction.

Chronology chart depicting the evolution of Cycladic figures.

There is no one-size-fits-all explanation. We find female, male, intersex, and abstract figures that can be standing, seated, or reclining, alone or in groups. Women with different physical attributes cover their solar plexus with their arms folded left over right as though guarding or holding something in. Slim or stocky men were sculpted as flutists, harpers, hunters, or warriors. These figures must be considered within a range of possibilities. The presence of pairs of flutists and harpers, for example, suggests that part of their meaning must be connected to early rhapsodists who regaled their audiences at gatherings with songs and tales of origins and exploits, perhaps including those of distant lands and earlier times.[8]

Marble seated harp player, 2800–2700 BCE. Late Early Cycladic I–Early Cycladic II. Marble, 2 15/16 × 5 15/16 in. (7.4 × 15.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY (47.100.1)

Most prolific are the canonical naturalistic figure types that appear in the Early Cycladic II period, a prosperous time due to increased copper alloy production and widespread exchange networks. These figures range from a tiny 6.2 centimeters to 1.53-meter-tall statues that recall the later marble kore and kouroi erected in Archaic Greek sanctuaries and cemeteries, either as images of the divine or humans in their service during the seventh to fifth centuries BCE. The latter life-sized figures could have been commissions by successful entrepreneurs or communities destined for display on the island of Keros, where recent fieldwork has produced hundreds of fragments of figures large and small and other finds that indicate a central shrine with rock shelters at Kavos opposite a settled promontory at Dhaskalio.[9]

Marble female figure, ca. 2700–2400/2300 BCE. Early Cycladic II. Marble, 8 1/2 × 34 in. (21.6 × 86.3 cm). Leonard N. Stern Collection, Loan from the Hellenic Republic, Ministry of Culture (L.2022.38.47)

Many types of stone were readily available to the islanders, such as basalt and schist, and the native copper that they smelted to cast tools and weapons. Much simpler to craft and just as enduring were the fired pottery vessels and animal figures they used domestically and as grave offerings. Yet Early Cycladic artists chose marble, perhaps because of its translucent and crystalline nature, which captures the sun’s light and endows the finished works with their own brilliant inner luminosity.

Marble female figure, ca. 2500–2400/2300 BCE. Early Cycladic II. Marble, 2 13/16 × 6 11/16 in. (7.2 × 17 cm). Leonard N. Stern Collection, Loan from the Hellenic Republic, Ministry of Culture (L.2022.38.151)

Ancient societies regarded their gods and goddesses as supernatural beings who controlled the cosmos and created humanity to serve them, often meddling in human affairs. As such, they had to be appeased with invocations and offerings, usually by gifted individuals who professed the ability to mediate on humanity’s behalf, allowing the divine to enter and speak through them. Such intermediaries have always existed at the interface between the divine and the mundane. Even kings and warlords were secondary to these divinely inspired mediums, who played vital roles in each person’s destiny from conception to death and beyond.

Midwives, who represented or embodied the goddess of maternal care, were the most powerful of all, guiding people through puberty, marriage, and childbirth. In ancient Greece, women who assumed this role were associated with the Pleiadian nymph Maia, whose name was interchangeable with Gaia, Mother Earth. The Maia, or Mammē, the Greek word for midwife or nurse, was the most important, venerated, and feared person in the community because she appeared to hold sway over life, death, and even a newborn’s gender.[10] She was present at both the beginning and end of most people’s lives and at the countless moments of joy and sorrow between. For this, she was revered and despised, the former when the gods granted the desired outcome, the latter when they did not.

She was present at both the beginning and end of most people’s lives and at the countless moments of joy and sorrow between.

The oldest Greek goddess of childbirth was Eileithyia, whose cult can be traced to the end of the Bronze Age in her cave sanctuary at Amnisos in Crete. In Greek myth, it was Eileithyia whom Leto’s handmaids summoned to Delos to help alleviate her birth pangs as she delivered Artemis and Apollo. The divine midwife’s cult was widespread throughout Greece and the islands, usually practiced in remote rock shelters and caves that resemble wombs where people traveled to seek assistance and pay homage. The setting for the sanctuary postulated for the Cycladic goddess at Kavos in Keros works well as a remote location with rock shelters along a cliff that faces the sea.

The life-sized figures could be images of this goddess at her sanctuary in Keros, while the smaller, more portable female figures could have been charms that the Maia infused with the sun’s rays and other powers they used in their ritual practices. The predominance of the female figures would indicate the Maia’s preeminence in Early Cycladic society. The male figures could have belonged to their masculine counterparts, including the musicians and bards who channeled their male god of music, a prehistoric Apollo, to sing songs and hymns to their gods and hunter-warriors who embodied their own gods of the hunt and battle. The figures that display both female breasts and a penis recall the “third gender” in shamanic practices in which the intermediary incorporates both female and male aspects of the divine beings they embody during rituals and ceremonies.[11]

Marble male figure, 2400–2300 BCE or later. Early Cycladic II. Marble, H. 14 1/8 in. (35.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY (1972.118.103)

Individuals born with congenital traits that allowed them to embody both sexes could have assumed this role. The ancient Greeks explained this through the mythical union of the nymph Salmacis and Hermaphroditus, the son of Hermes, the god who mediated between the visible and invisible worlds guiding souls in the afterlife, and Aphrodite. This merging of genders, idealized in Plato’s Symposium, was a popular theme in ancient Greek and Roman art. Modern medicine largely attributes intersex, pseudohermaphrodism, and hermaphrodism to the consanguinity common in endogamous relationships.[12] Recent analyses of ancient DNA have demonstrated such a high frequency of endogamy in the early Aegean societies that we might expect to see many more representations in Aegean art.[13]

Controlled excavations of Early Cycladic cemeteries have shown that the marble figures belonged to a very small percentage of the population, some of whom possessed several examples, while the majority had none. The figures’ ownership, and the fact that some were repaired several times, suggests that the few individuals who owned them kept them complete and repainted them during their lifetime and then, in some instances, were buried with them. Some graves also contained small jars and bowls with pigments that could have been used to paint or tattoo humans both in life and in the afterlife.[14] It was common practice to dismember the marble figures methodically at the ankles, knees, waist or chest, and neck, perhaps to ensure that their light or essence was dispersed and could not re-enter them. Such a “killing” of the figure may have coincided with their owner’s disincarnation, as often only fragments of the figure are entombed. But this was also the practice in the sanctuary at Kavos in Keros, so there may have been more complex reasons to render these figures powerless when they were deposited there, perhaps at the conclusion of a specific rite or festival.

Who were these Early Cycladic figures? I suspect that we are looking at a variety of artifacts linked by their common iconography, marble composition, and frequency of use in an early cult of fertility, childbirth, and regeneration combined with that of healing and music. The sanctuary at Kavos ceased to function during approximately two centuries of extreme aridification coincident with ancient Egypt’s First Intermediate Period[15]; this climatic event may have contributed to population movements and decline throughout the Mediterranean until the return of wet winters and renewed abundance. By then, the population in the Cyclades had changed, and the Keros cult center was a distant memory. All that remains are these evocative images of a time when people may have gathered to celebrate birth, song, death, and rebirth as never-ending cycles of being.

Notes

[1] Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, Book 1, chapter 4.

[2] Arnott, Robert, “Cycladic Objects from Ios Formerly in the Finlay Collection." BSA 85, 1990, pp. 1–14.

[3] Caubet, Annie, Pat Getz-Gentle and Marielle Pic, “Trois figures cycladiques en marbre du IIIe millénaire.” Revue de la Bibliothèque nationale de France n° 45 2013, pp. 67–73.

[4] Perrot, G. and Chipiez, C., Histoire de l'art dans l'antiquité, vol. vi: La Grèce primitive, l'art mycénien, Paris, 1894. 180.

[5] Sotirakopoulou, Peggy, The “Keros Hoard:” Myth or Reality? Searching for the lost pieces of a puzzle, Athens: N.P. Goulandris Foundation – Museum of Cycladic Art, 2005, pp 71–2.

[6] Graves, Robert, The White Goddess: a historical grammar of poetic myth, Creative Age Press, New York, 1948. See also Neumann, Erich, The Great Mother: An Analysis of the Archetype, Pantheon, 1955.

[7] Gimbutas, Marija, The Gods and Goddesses of Old Europe 7000–3500 B.C. Myths, Legends and Cult Images. London, Thames and Hudson, 1974.

[8] Mertens, Joan R. “Some Long Thoughts on Early Cycladic Sculpture,” Metropolitan Museum Journal 33 (1998), 7–22. These figures are contemporary with the Early Dynastic Period in Mesopotamia, ca. 2900–2350 BCE, when the exploits of a legendary King of Uruk could have provided the basis for the Epic of Gilgamesh, which travelling bards sang throughout the ancient Near East and beyond.

[9] Renfrew C., O. Philaniotou, N. Brodie, G. Gavalas & M.J. Boyd (eds.) The Sanctuary on Keros and the Origins of Aegean Ritual Practice: The Excavations of 2006–2008, vol.II: Kavos and the Special Deposits. (McDonald Institute monographs) Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 2015.

[10] Zimmermann Kuoni, Barbara Simone, Midwives of Eileithyia. Tracing a female healing tradition in prehistoric Crete, PhD Thesis, Trinity College Dublin, 2019.

[11] Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo, 2015. Relative Native. Essays on Indigenous Conceptual Worlds. HAU Books, Chicago, 2015, 252.

[12] Bashamboo, Anu and Ken McElreavey, “Consanguinity and Disorders of Sex Development,” Human Heredity 2014, 77, pp. 108–117.

[13] Skourtanioti, Eirini and others, “Ancient DNA reveals admixture history and endogamy in the prehistoric Aegean,” Nature Ecology & Evolution 7(2), 2023, 1–14.

[14] Hendrix, Elizabeth A. “Painted Early Cycladic figures: An exploration of context and meaning,” Hesperia 72, 2003, pp. 405–46.

[15] Monica Bini, and others, “The 4.2 kaBP Event in the Mediterranean region: an overview,” Climate of the Past 15, 2019, pp. 555–577.

Further Reading

Getz-Preziosi, Pat, Early Cycladic Sculpture: An Introduction. Rev. ed. Malibu, Calif.: Getty Museum, 1994.

Getz-Gentle, Pat, Personal Styles in Early Cycladic Sculpture, Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2001.

Graves, Robert, The White Goddess: a historical grammar of poetic myth, New York: Creative Age Press. 1948.

Marthari, Marisa, Colin Renfrew & Michael Boyd (eds.) Early Cycladic Sculpture in Context, (Papers Presented at a Symposium Held at the Archaeological Society at Athens, 27–9 May, 2014). Oxford: Oxbow. 2017.

Renfrew, C. and others, “The sanctuary at Keros in the Aegean Early Bronze Age: from centre of congregation to centre of power,” Journal of Greek Archaeology 7, 2022, pp. 1-36.