Will Wilson’s photography centers the past, present, and future of Indigenous cultural practice. Growing up on the Navajo Nation, Wilson saw firsthand the environmental and health impacts of the American colonial project and the history of uranium extraction and processing in the American Southwest. His landscape photography and installation work incorporates Navajo mythology, depicts the toxic post-apocalyptic environments Indigenous communities inhabit, and envisions rebirth and rehabilitation through Indigenous practices.

Wilson’s work also challenges the history of Euro-American anthropological photography of Native people, redeploying the method of tintype photography in a series of portraits capturing contemporary Native North America. His process in the Critical Indigenous Photographic Exchange (CIPX) is interactive and reciprocal; Wilson works with his subjects to decide how they are portrayed, gives the final photograph to the sitter, and keeps a scan for his portfolio. The result is a vast digital archive that includes his famous Talking Tintypes, which merge nineteenth- and twenty-first-century storytelling forms. Wilson recently shared his work and process, showing the development of tintype photographs in action, at an Artist’s Workshop Demonstration held at The Met in celebration of Native American and Indigenous Heritage Month.

He spoke with Patricia Marroquin Norby, associate curator of Native American art at The Met, about his influences, methods, and artistic vision. Their conversation has been edited and condensed for publication.

Will Wilson processes a tintype photograph at The Met

Patricia Marroquin Norby:

You are engaged with a number of different areas of photography: sweeping landscapes, self-portraits, tintype portraits, and even drone photography. I was wondering if you could talk about that really diverse engagement. What is all of that about for you, and how does that influence your work?

Will Wilson:

In some ways, it's the nature of being a photographer and maybe being an Indigenous photographer in particular. The land and its relationship to people—or how they're almost the same thing—informs my practice, my process. And being a lens-based artist, where the technology is always evolving and offering new opportunities to create imagery in new and exciting ways. It's almost part of the job.

Mexican Hat Disposal Cell Redux in Halchita, Utah, Navajo Nation. Photograph by Will Wilson

As I continue working and learning about the different histories of photography associated with what's now the American Southwest, or Dinétah, I look to “process” as a way that viewers can enter the work, and to think about history. What does this strange old-time-y-looking photography being made today mean? Hopefully, it points to different historical moments when those processes were current. After 1848, when the US acquired what's now the American Southwest, there were survey teams sent out, and they used the wet-plate collodion process to image what they perceived as a resource to be exploited. So I'm interested in working through the process to infer this history, but also from the perspective of a modern day practitioner, using the technology at hand to create something new and dynamic. Blending these elements has been interesting and exciting.

Norby:

What's interesting about your work is that it simultaneously engages with history—specifically Indigenous peoples' histories and the tension with the settler-colonial gaze—and it looks to the future in many ways. I want to go all the way back to the early 2000s and your Auto Immune Response (AIR) series because that's what first drew me to your work. It's such a powerful series, and you describe it as a post-apocalyptic future. How did that project first get started? What were you thinking at the time? And now here we are, twenty years later. What are your thoughts about it now?

Wilson:

One of my mentors in grad school was Patrick Nagatani, a Japanese American photographer. He had just come out with a book called Nuclear Enchantment that was about the American Southwest and his personal relationship to that geography, as a child in the internment camps during World War II and in this site of the development of the atomic bomb. He did a lot of “performative photography,” creating personae and imaging himself in different critical contexts.

© The Estate of Patrick Nagatani, courtesy Andrew Smith Gallery, Arizona

I've used that approach as a stepping-off point to imagine myself as an Indigenous person remembering the future. The idea of Indigenous Futurities hadn't been articulated yet, but it was very much in a lot of people's minds. In the Auto Immune Response series, I'm thinking about Indigenous people as having already survived an apocalypse, referencing environmental injustice on the reservation, particularly the legacy of uranium extraction and processing on the Navajo Nation. We all have family members who were affected by this traumatic legacy. Many people who worked in the mines and/or processing mill got strange cancers and died.

In boarding school, I took care of this young man who had an affliction that is now referred to as Navajo neuropathy, but at the time I don’t think anybody really understood what it was. It's associated with exposure to radioactive materials, either in the womb or very early on in someone's developmental life. We’ve all become very much aware of this history, but it was something that I wanted to process and work through in the AIR series.

Auto Immune Response. Photograph by Will Wilson

Norby:

You and I were both in art school at the same time, and in the ’80s and ’90s, OSHA (Occupational Safety and Health Administration) was being passed. So there was this new awareness of artists working with dangerous materials. I think it really brought about this level of awareness about the dangers of both our personal as well as our professional environments. This was also the first generation where we were introduced to environmental devastation. And I can see how those ideas really resonate in your imagery. I want to go to that figure, though, in the Auto Immune Response series. I know these are self-portraits in a sense, but they’re also not. There’s something so striking and so haunting about those images that really grabbed me.

Wilson:

Yes, the AIR project is ongoing by the way. I’m still making work from that series, and I imagine I’ll be doing it until I can’t manage a camera anymore. It is following the trajectory of my life and of my practice.

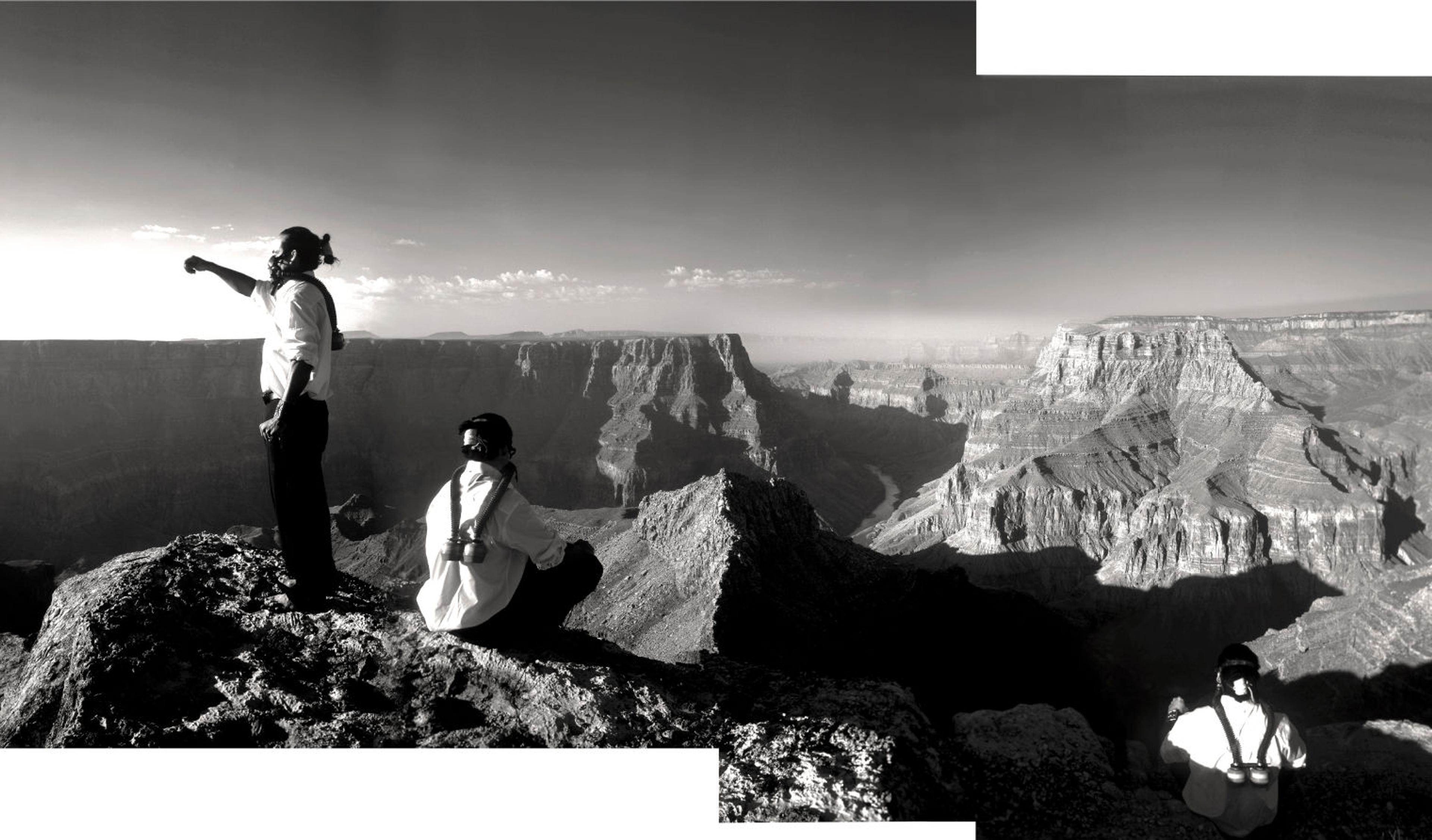

I don’t think I was aware of it at the time, but subconsciously, I think, I was reflecting on myself as a mixed-race person and my experience as a kid on the reservation and as a boarding school survivor. All this was in the background as I was creating those monumental panoramic photographs. I was also attempting to use performance as a way to disrupt the history of American landscape photography, performing in the land, for the lens, to create a kind of landscape photography as theater.

Auto Immune Response. Photograph by Will Wilson

Later, I incorporated elements of the Navajo creation story. There are these hero twins, Born of Water and Monster Slayer, who rid the world of monsters in order to make this iteration of humanity viable. The monsters became a metaphor for environmental harm that had occurred, and the twins, performed by me, are battling with these issues and ideas. The characters find themselves alone; they don’t know what has happened. Something traumatic has occurred, but they have to figure out how to deal with it, how to survive. So in that first set of images, by the end of the series, the protagonist—which is what I call the character I perform—builds himself a house, a hogan. And that house, actually, has a life of its own. The hogan, which is a one-room, customary Navajo structure, has become the Auto Immune Response Laboratory (AIR LAB). It functions as a site-specific installation where the shift from fiction and fabulation to reality and research occurs. It’s a greenhouse for the cultivation of Indigenous food species, a nursery for pollinator and dye plant species, and a research facility for the work of the protagonist.

In 2022, at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts, AIR LAB was installed in collaboration with the horticulture team from the University of Utah’s Red Butte Garden. We cultivated phyto-remediation species that are actually able to draw heavy metals out of the ground. The University of Utah is particularly interested in this work because of remediation research dealing with contamination from heavy metals in the Southwest. I got to learn all about these species. Like how, at Chernobyl, they planted dwarf sunflowers in order to draw radioactive contamination from the earth. So it’s not just about the catastrophe. It’s also: How do you move forward? How do you use this art practice as an opportunity to figure out solutions for these incredibly complex problems?

Auto Immune Response. Photograph by Will Wilson

Norby:

You talk about the protagonist waking up, and he’s all alone in the world. How does he respond to that moment? I noticed in the images that it looks like he’s praying, and he’s dropping cornmeal, and he has his hair tied in a traditional way. I wondered if you are comfortable touching on that.

Wilson:

Praying with corn pollen is a central gesture in that series. And it is about trying to figure out what Indigenous remediation might mean, trying to reengage with a lost connection to the land. In my research, I came across a quote by a Diné elder explaining how the holy people offered humanity two yellow powders: one of those being corn pollen, a life-giving force, and the other a yellow powder with an inherent force. The Diné were to choose one and to leave the other undisturbed. This story has figured prominently in my installation work. The AIR project, though it is primarily photographic and performative, in its full form is also accompanied by sculpture. In one iteration, there’s a tower that is supposed to reference the tower that they used for the first atomic bomb test—Oppenheimer’s tower. In my version, instead of plutonium or uranium at the core, there’s corn pollen. So it’s sort of a beauty bomb instead of a bomb of destruction.

Left: Auto Immune Response Laboratory hogan. Right: Corn pollen-core tower. Photographs courtesy of Will Wilson

Norby:

Let’s move forward now to CIPX, the Critical Indigenous Photographic Exchange. Could you describe that briefly?

Wilson:

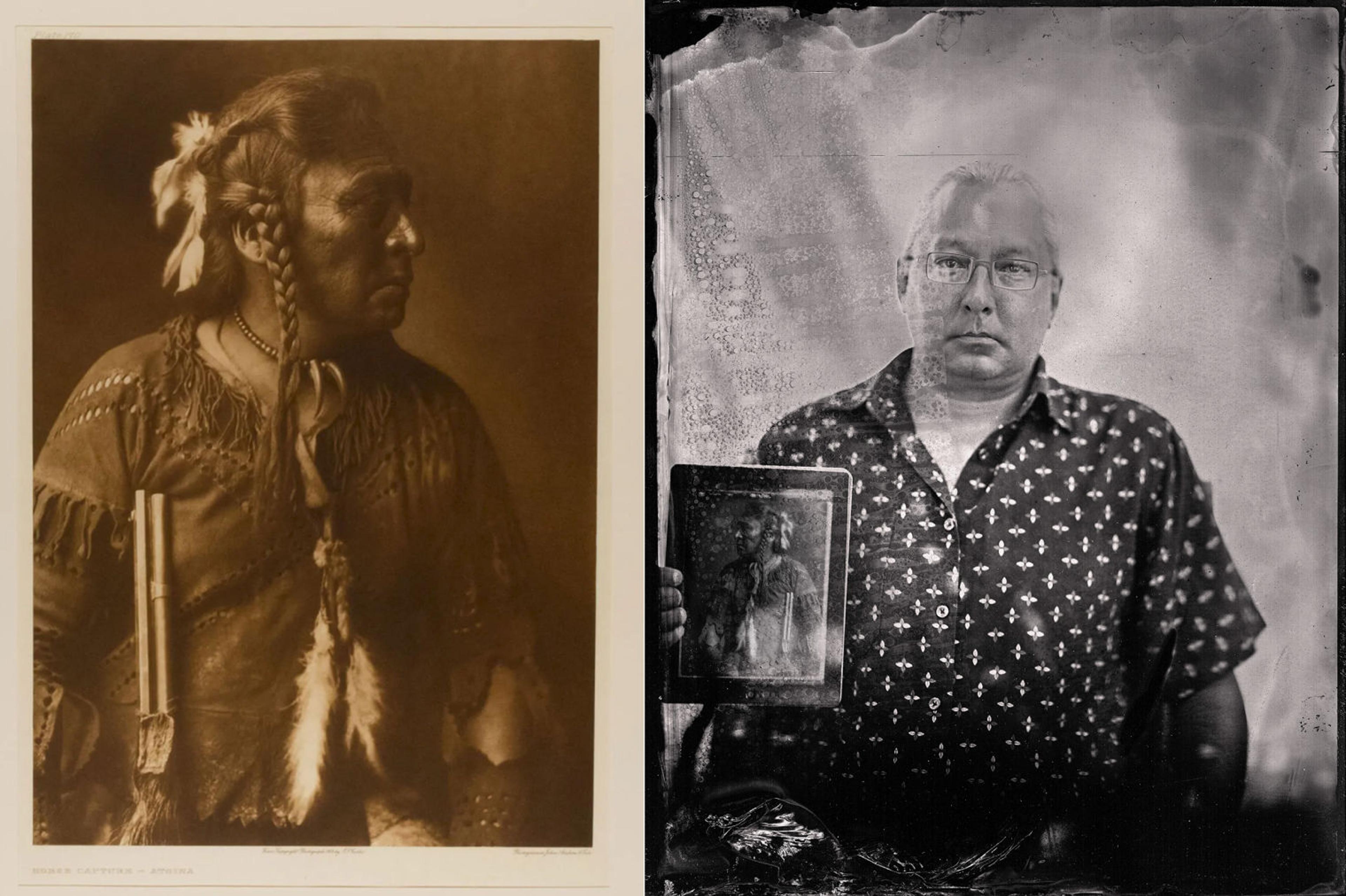

The tagline for that project is “What if Indians invented photography?” Would there be a different set of practices or protocols associated with making an image of somebody?

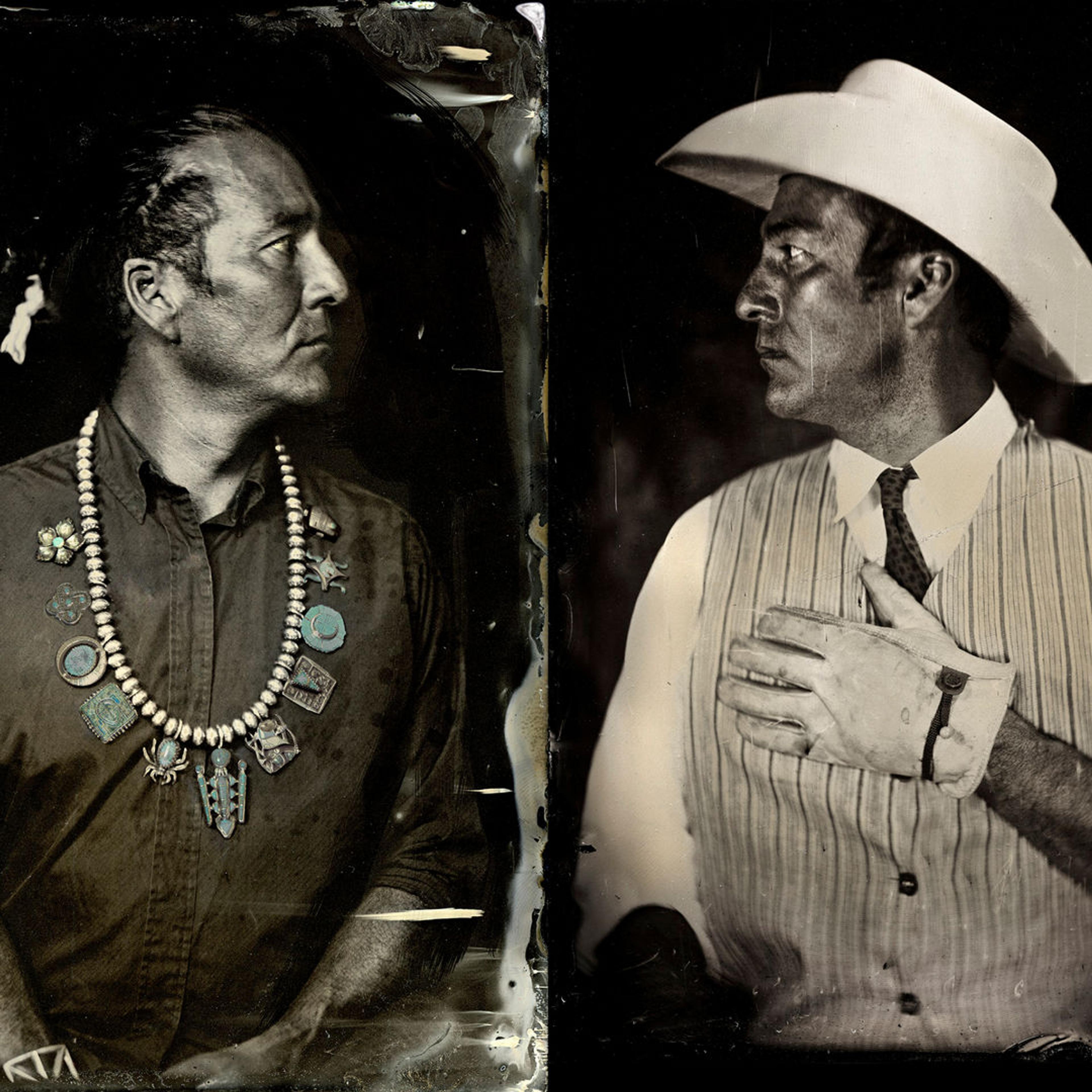

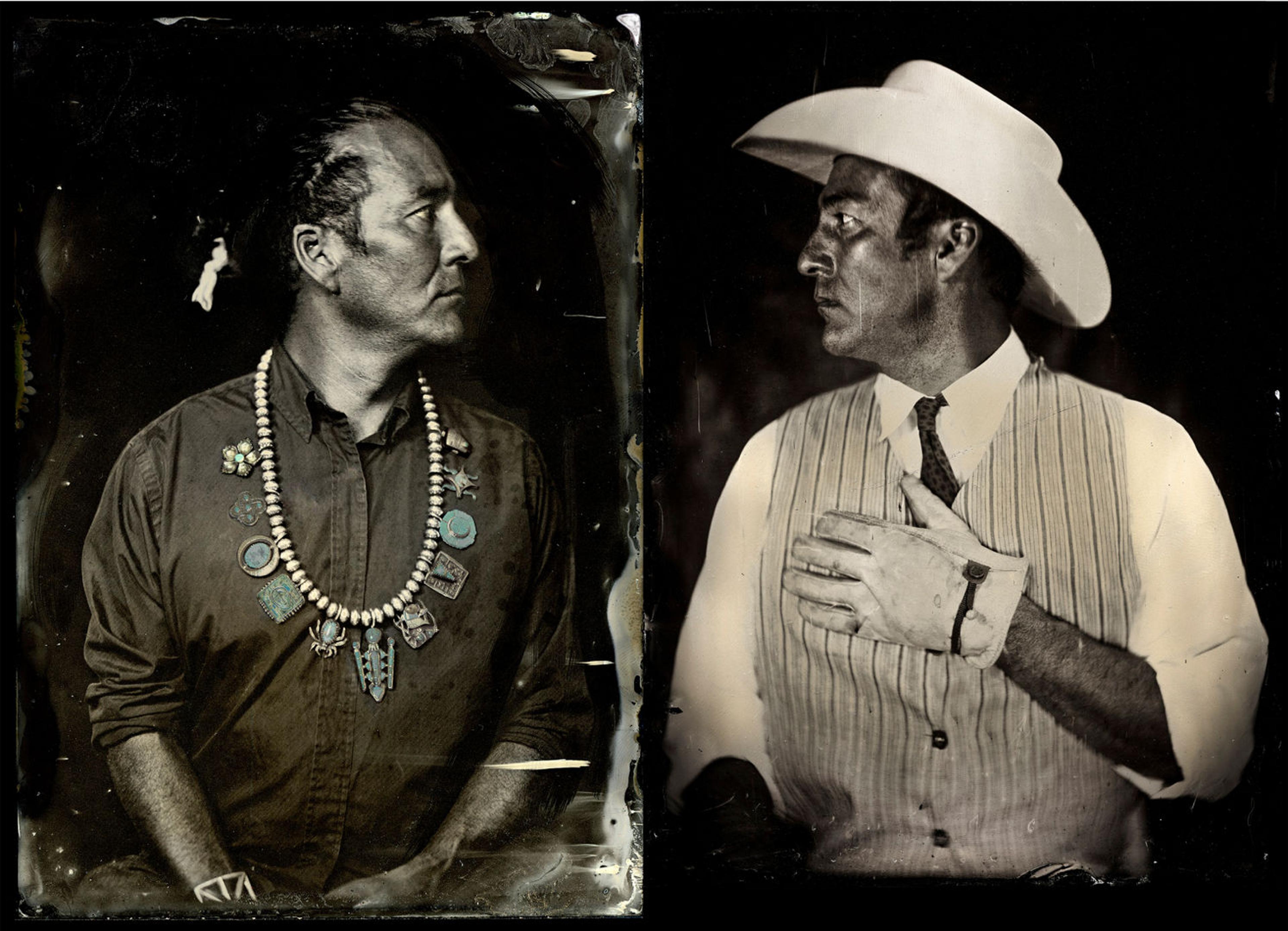

In thinking about what photographic representation in portraiture means to Indigenous people historically, I invoked Edward S. Curtis, who was creating typologies of people in a strange ethnographic way, reinforcing a pseudoscience built on a foundation of white supremacy. So thinking about that history, what does it mean for me as an Indigenous photographer to be creating these images in today’s world? What does it mean to capture an image of another person? Part of the project uses the image-making process to slow down and have this hopefully meaningful engagement with another person about what it means to make their portrait. This slow conversation happens over the course of maybe thirty minutes. I get to share this old, historic photographic process where we make our own film, and then in the end, the photographic object is gifted back to the subject. The sitter gets the work as a gesture of reciprocity, and I get a scan of it, so over the years I’ve amassed a digital archive of thousands of portraits. Ultimately, the project is about investigating a relational aesthetic, and the performance of identity, agency, and exchange at the heart of portraiture.

Left: Horse Capture photographed by Edward S. Curtis. Right: Joe Horse Capture holding the photo of his ancestor created by Curtis, photographed by Will Wilson

Norby:

You’re working with collodion for the tintype process. Could you break down how that process works?

Wilson:

You take this substance called collodion, which is essentially cotton boiled down in nitric acid. It’s super sticky, so it will stick to anything, including glass. That becomes the binder. Step one involves pouring the collodion on the plate—it’s not light-sensitive at this point. Once it dries, and it dries almost immediately, you put it in a bath of silver nitrate. The silver combines with the collodion and the chemical process makes light-sensitive silver salts—silver halides. At that point, three minutes later, after it’s been immersed in this tank, it’s photo-sensitive, so you do have to use a safe light. You take it out in the dark room, and you’ve essentially made your own piece of 8x10 film in my case. You now have about fifteen minutes. That’s the wet-plate part of it; it has to stay wet. If it dries, you won’t get an image. That’s why you have to have a dark room with you whenever you do this. The dark room does two things: it enables you to make your film and then develop it before it dries out. This creates an opportunity to share a really cool performative engagement. The CIPX project is really about that interaction. That’s the beauty of the process. You get to share an historic photographic process and it reinforces the relational aesthetic.

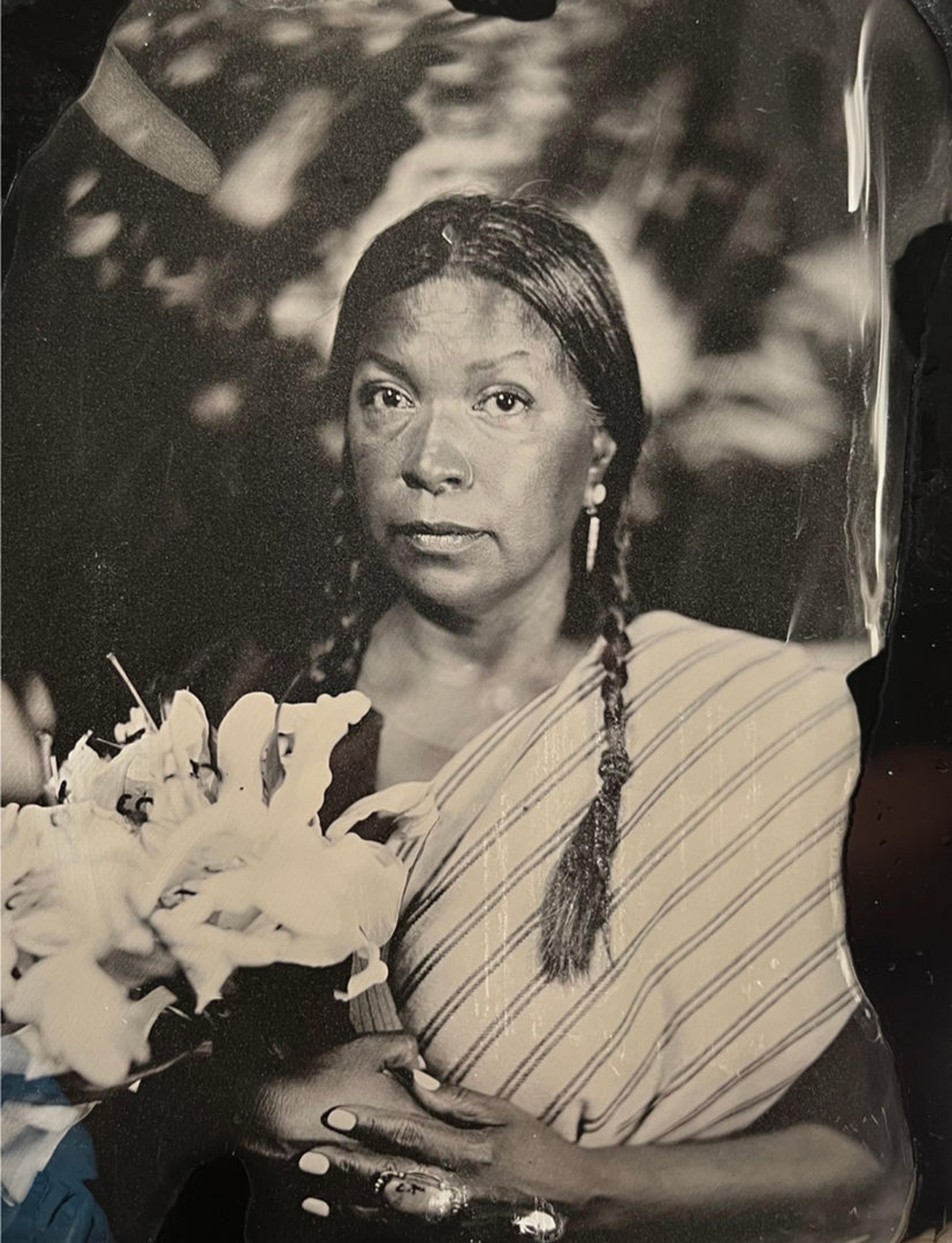

Critical Indigenous Photographic Exchange. Photograph by Will Wilson

Norby:

As one of your former sitters, I’ve gone through the process. Something that’s quite remarkable is your openness to engaging with your sitter, demonstrating and talking about the process. There’s a conversation. There’s a sense of collaboration with creating these images. And there’s also this performative aspect, this Wizard-of-Oz element where you’re underneath this curtain with a camera, and then we go into a dark room and it’s all quite magical.

Wilson:

If you have experienced the traditional analog darkroom, you’ve seen your image emerge in the developer; it’s amazing. It’s like alchemy. With the wet-plate process, this happens in the fixer, because when you develop a tintype, it initially comes up as a negative image in the developer. It’s a little spooky. But then you put it in the fixer, and there’s this remarkable reveal, where the image fogs away and then comes back as a positive image. Every time I witness this it takes me back to that moment when I first fell in love with photography. It’s very simple and very beautiful, and that is a really cool thing to share. I can count on people being amazed. Every time I share this amazement with my sitters, it fuels me.

Patricia Norby photographed by Will Wilson

Norby:

I want to talk about your Talking Tintypes. There's a wonderful image of your wife and partner, Carla, who’s a violinist. How did the Talking Tintype evolve out of the CIPX project?

Wilson:

Early on in the project, in 2013, I was flipping through a magazine, and it had an augmented-reality (AR) advertisement. It said download the LAYAR app, scan the page, and you’ll experience the AR content. It was a eureka moment for me because I had been trying to figure out how to do that exact thing with my tintypes, to bring them to life, in order to give voice to my subjects. I wanted to disrupt the power dynamics between the photographer and the sitter. In bringing nineteenth- and twenty-first-century technologies together, I’m hoping to reshape our understanding of the relationship between Indigenous people and photography. This merging references the past while creating a new narrative form, challenging and transforming our perceptions of portraiture in an innovative combination of old and new.

Madrienne Salgado photographed by Will Wilson

So I asked, who would be the best people to work with in developing this new form. Carla, my partner in this life for the last thirty years, was gracious enough to work with me on countless takes to make it happen. Performers and politicians make for good Talking Tintype collaborators because they can speak on demand very easily. Dancers are also amazing to work with as a photographer, bringing exquisite movement back into the historic photo process is really exciting. I had the opportunity to collaborate with Adam McKinney, formerly a professor of dance at Texas Christian University in Fort Worth, Texas, who is now the artistic director of the Pittsburgh Ballet. Adam had conducted research around a very traumatic event in Fort Worth’s history, the racial terror murder of a man named Mr. Fred Rouse. He could not find a photo of Mr. Rouse, so he used his own body and choreography to enact this history. Adam invited me to collaborate with him by creating a series of Talking Tintypes. This resulted in SCAB: Honoring the Memory of Mr. Fred Rouse. It was another powerful way to give voice back to the photograph, to tell important stories.

SCAB: Ku Klux Klan Klavern No. 101 Auditorium, 1012 N. Main Street, Fort Worth, TX, 2019. Photograph by Will Wilson

Norby:

How does the engagement of Native or Indigenous peoples with photography challenge the stereotypes and settler-colonial framing of historical depictions of Native people? I’ve thought about this a lot. Aren’t we just replicating the same thing if we’re just doing a series of tintype portraits?

Wilson:

I think it's an exciting time for Indigenous photography. There are more people than ever before working in this arena. In many ways, we've done the work that enables the next generation of Indigenous photographers to not have to worry about these issues as much. I think of people like Hulleah Tsinhnajinnie or Shelley Niro, and also the work that you and I have done over the years, to challenge those stereotypes. We’ve done the work that now enables the next generation to move beyond these issues. The Talking Tintypes project is firmly grounded in challenging settler-colonial depictions of Indigenous people, but it is also trying to transform the ethos of portraiture from an Indigenous perspective. I think the Auto Immune Response series—with its monumental, full-blown color landscapes functioning as a kind of theater—has also been seminal in moving our field away from those stereotypical representations.

Norby:

There’s this real fascination with images of Native people, and I don’t know if people talk about that a lot. Why do you think that historically, settler communities, but moving forward, contemporary audiences—why do you think they’re so drawn to images of Indigenous people?

Wilson:

We can't have cowboys without Indians, right? [laughs]

I mean definitely there’s the legacy of this othering process that is foundational to American identity. I mean maybe it’s one of the most culturally disseminated relationships between settler and Indigenous communities, because this construction happens all over the world. But in the American context—the history of Western movies in Hollywood, for example—we’ve devoted the most screen time historically to that fraught relationship. From the standpoint of an Indigenous practitioner, it’s great fuel for research and for making work. We’re definitely having our moment, which is great. It’s about time. Hopefully it’ll continue, and I think it will. But I don’t know. We’re beautiful people. How about that?

Norby:

I like that.

Scan the QR code to download the Talking Tintypes app