What was the Harlem Renaissance? More than a specific time or place, it was a mindset. During the Great Migration, major cities across America proved fertile ground for artists and intellectuals fleeing the Jim Crow South. In this episode we hear about Alain Locke’s famous anthology The New Negro: An Interpretation, which gathered some of the best of fiction, poetry, and essays on the art and culture emerging from these communities. Locke’s volume demonstrated the diverse approaches to portraying modern Black life that came to characterize the “New Negro” and embody some of the era’s highest ideals.

Follow Harlem Is Everywhere wherever you listen to podcasts:

Listen on Apple Podcasts | Listen on Spotify | Listen on YouTube | Listen on Amazon Music

Visit The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism through July 28.

Supported by

Transcript

JESSICA LYNNE: Welcome to Harlem Is Everywhere brought to you by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, a celebration of the exhibition The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism.

I’m your host Jessica Lynne. I’m a writer and art critic. This is episode one, The New Negro.

I write about Black visual artists throughout the diaspora and I’m especially interested in Black Southern life and culture. I grew up along the Virginia coast but I’ve been in New York now for practically all my adult life.

And even though I’m “up south,” as they say, I see so many aspects of my childhood in the city, especially in Harlem. From the soul-food restaurants to the hair salons, and the storytelling on stoops that reminded me of what would happen on the porches back home. Even when I first got to Harlem, I felt like I’d always been in Harlem.

To bring this time period to life beyond the walls of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, we have a podcast for you. This podcast is a resource for curious ears, a conversation about a time and place, and a look at the first Black American–led movement of international modern art.

In this episode, we’ll hear from guests featured throughout the series. We’ll explore the significance of the Great Migration and the publication of Alain Locke’s groundbreaking anthology The New Negro. We’ll learn how Historically Black Colleges and Universities have acted as shepherds of this artwork. And we’ll recognize this time and these artists with the respect they deserve.

—

MONICA L. MILLER: I think there was a hunger for African American culture to be recognized as art…

RICHARD J. POWELL: Whether it’s Chicago or Washington, D.C. or New York City. There’s this conflation of African Americans or people from the Caribbean kind of living, again, these new lives…

MARY SCHMIDT CAMPBELL: I was really struck by the extent to which the artists had a very fierce sense of self-determination…

MILLER: And also a conversation that was initiated between Harlem Renaissance artists and ordinary Black people, no matter where they were.

POWELL: This is such a pivotal moment in Black America. So many African Americans have moved from the rural South to the urban North…

CAMPBELL: And were able to articulate on their own terms what they believed and how they believed African American artists should express themselves.

BRIDGET R. COOKS: What’s interesting about the afterlife of the Harlem Renaissance and its art is that there hasn’t been very much sustained attention on the art of the Harlem Renaissance and the artists that produced it.

DENISE MURRELL: If you were to take a survey of twentieth-century art or modern art when I was taking classes, they would go through the school of Paris, German Expressionism, if they’re talking about the American side—Stieglitz, Hopper, etc.—no mention really of the Harlem Renaissance. The only way to get to study the Harlem Renaissance was to take one of the vertical courses, one hundred years or, you know, two centuries of African American art. You have to seek the period out.

LYNNE: Harlem exists simultaneously as a constantly evolving community and as a living archive of a people’s beauty. The Harlem Renaissance was a time when Black folks were using the things they had made—their contributions to culture—in order to add their stories to a larger American one.

After the Great Migration, many folks fled Jim Crow in the South for cities like Chicago, Philadelphia, and New York hoping for a fresh start, imagining a new future.

The Harlem Renaissance was a movement that turned thinkers and writers such as Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, and W. E. B. Du Bois into household names.

It was bold, exciting, and world changing. A time when Black people were able to express themselves in their own way to themselves. Not just in Harlem but throughout communities across America and overseas. The Harlem Renaissance was a mindset.

—

LYNNE: Denise is the curator of The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism.

MURRELL: Well hello, I’m Denise Murrell.

LYNNE: Her connection to Harlem is not only professional, it’s personal.

MURRELL: I was born in Harlem Hospital. My parents are both from North Carolina. The decades immediately following the Harlem Renaissance, the fifties and the sixties, are when my parents came to New York. I later came to understand them to be part of the later years or the middle years of the Great Migration.

LYNNE: At the beginning of the twentieth century, Black people living in the South began to migrate north. Southerners spread across the country to settle in various communities. They traveled as far as Los Angeles, Oakland, and Seattle. But the majority moved north to cities like Chicago, Detroit, and Philadelphia. New York had always had a Black population, with folks from all over the global Black diaspora.

MURRELL: But the migration from the South expanded those numbers exponentially. And Harlem—which was not built to be an African American neighborhood for a number of economic and other reasons—became the destination and very quickly became predominantly Black.

LYNNE: Among these people leaving home and family behind were artists. They traveled north with the hope of finding a way forward. In search of peers and community, seeking new audiences and opportunities.

POWELL: Moving to urban centers gave people a chance to kind of reimagine themselves. But that can be a little scary, too.

LYNNE: Here’s Richard J. Powell…

POWELL: I’m an art historian. I teach at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. And this fall, I’m in residence at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in the Lauder Center for Research on Modern Art.

LYNNE: Even though many were leaving behind dangerous circumstances in the South, taking a chance on yourself and leaving what you know behind can be frightening.

POWELL: There’s a great line from Richard Wright’s Black Boy where he talks about, “I flung myself into the unknown,” when he makes it from Mississippi to Chicago. And it is kind of like a trajectory. It is like kind of flinging yourself into this kind of concrete and urban and asphalt place. And you’re hoping that your dreams are going to come true, but you’re just not really sure.

LYNNE: The risks these folks were taking speaks to the willingness for change. Many of their parents would’ve been born into slavery. It’s hard to imagine coming from communities in Tennessee, Alabama, Florida, North Carolina….

POWELL: … South Carolina, or Georgia and hitting 125th and Lenox Avenue, coming out of the subway and on one hand being mesmerized, but on the other hand being a little scared.

LYNNE: It makes sense that when these artists found community and connected with other like-minded individuals it must’ve been all the more meaningful. The risk had been worth it. They were thriving, they were inspired, they were creating work that would come to define the Harlem Renaissance.

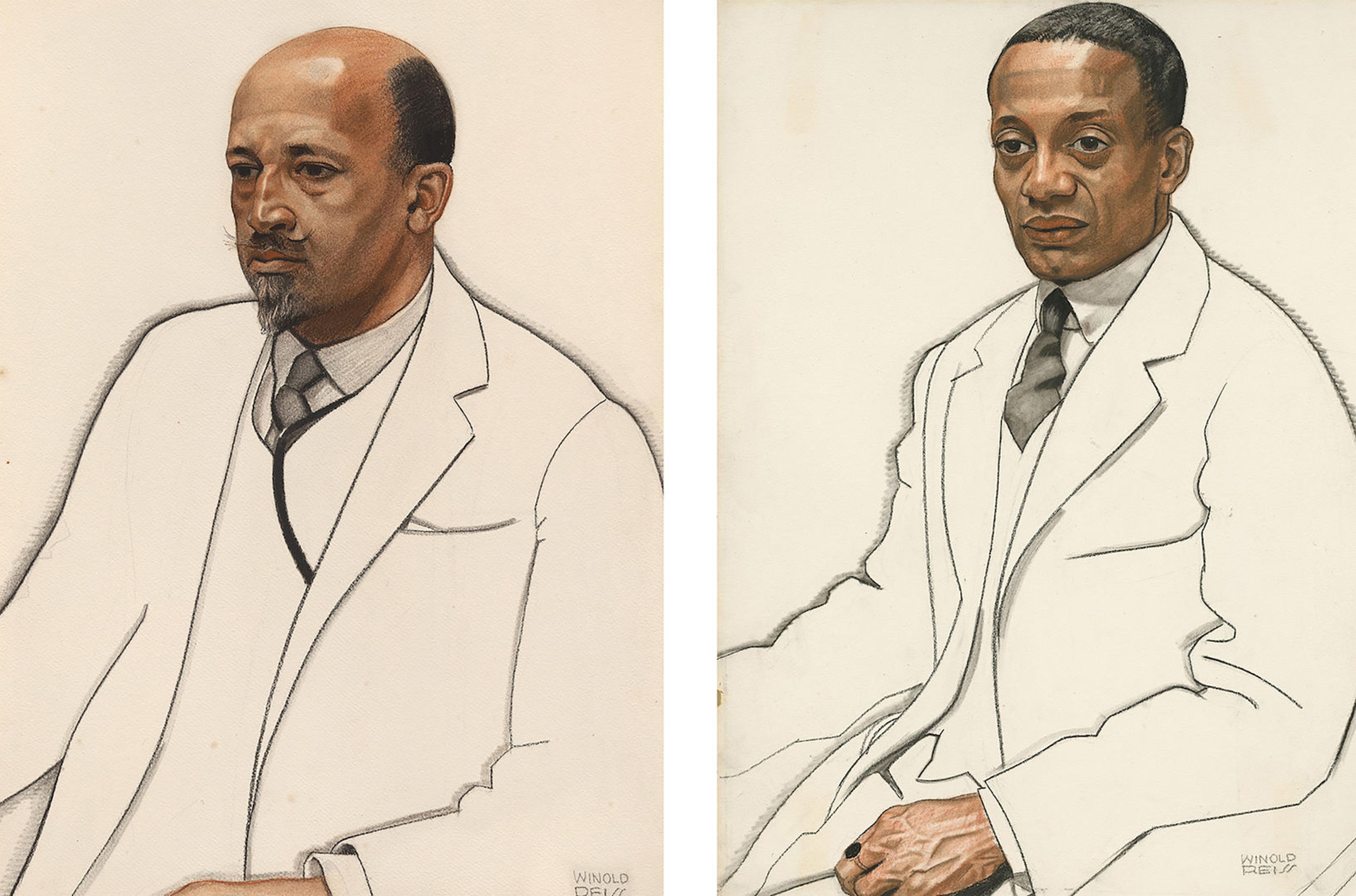

Many people are responsible for helping shape and mold the ideals of this period. But there are two names central to this story: the activist, historian, and sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois and the writer, philosopher, and educator Alain Locke. Here’s Denise…

Left: Winold Reiss (American, born Germany, 1886–1953), W. E. B. Du Bois, 1925. Pastel on illustration paper, 30 x 21 5/8 in. (76 x 55 cm). National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.; Purchase funded by Lawrence A. Fleischman and Howard Garfinkle with a matching grant from the National Endowment for the Arts (72.79); Right: Winold Reiss (American, born Germany, 1886–1953), Alain Leroy Locke, 1925. Pastel on illustration board, 29 7/8 x 21 5/8 in. (75.9 x 54.9 cm). National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D. C.; Purchase funded by Lawrence A. Fleischman and Howard Garfinkle with a matching grant from the National Endowment for the Arts (72.84)

MURRELL: Alain Locke was more rooted in the art world and avant-garde aesthetics. And encouraging artists to evolve a modernist visual vocabulary that was specifically African American.

LYNNE: Du Bois took a different approach.

MURRELL: W. E. B. Du Bois supported that, but he came at it from an activist point of view. He was the editor of The Crisis magazine, which was the monthly publication of the NAACP. And he said, “I don’t give a damn about any art that is not propaganda.” We’ve had propaganda thrown at us all of our lives, and we’re going to put our own propaganda out there.

So, you have these two: one is aesthetic and one is activist.

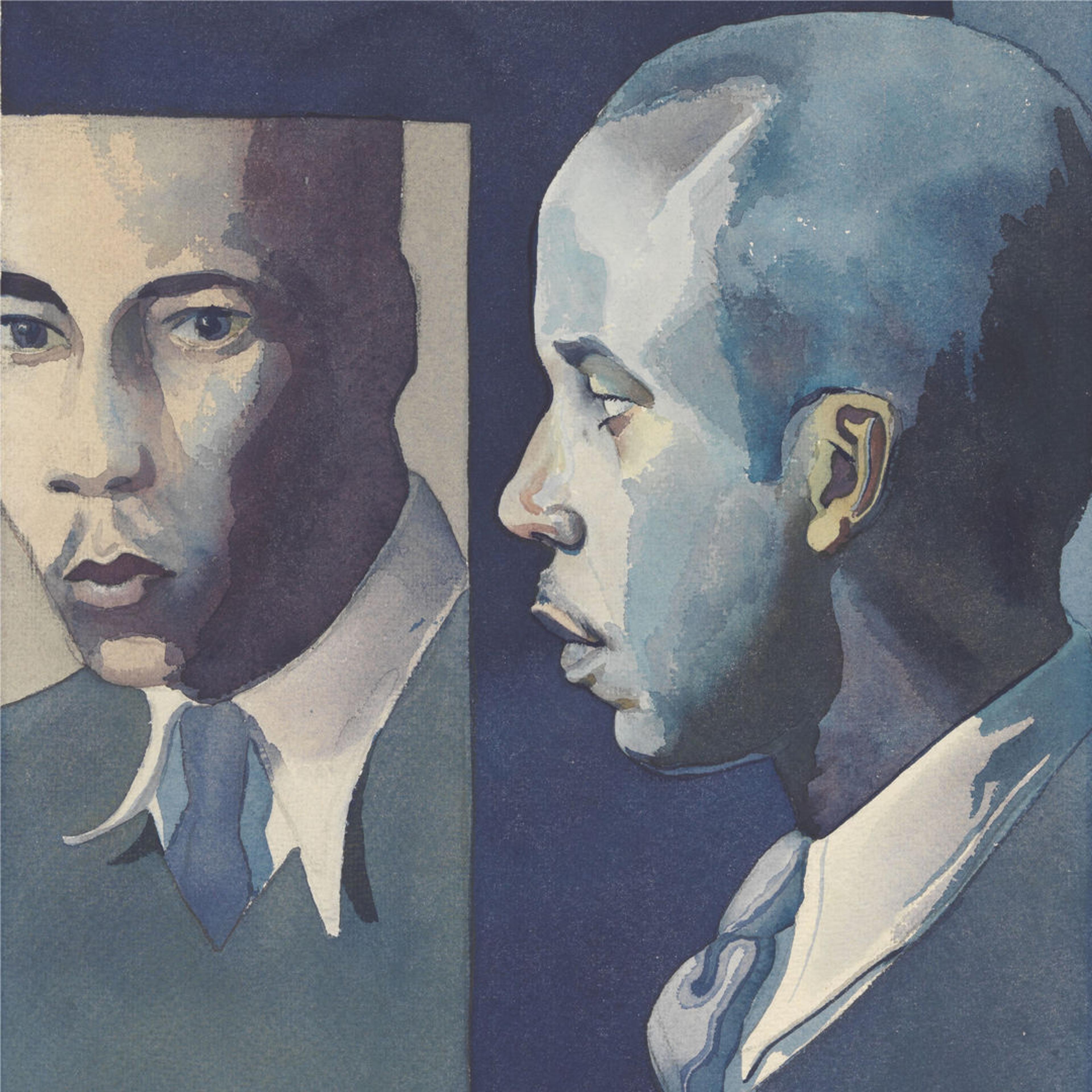

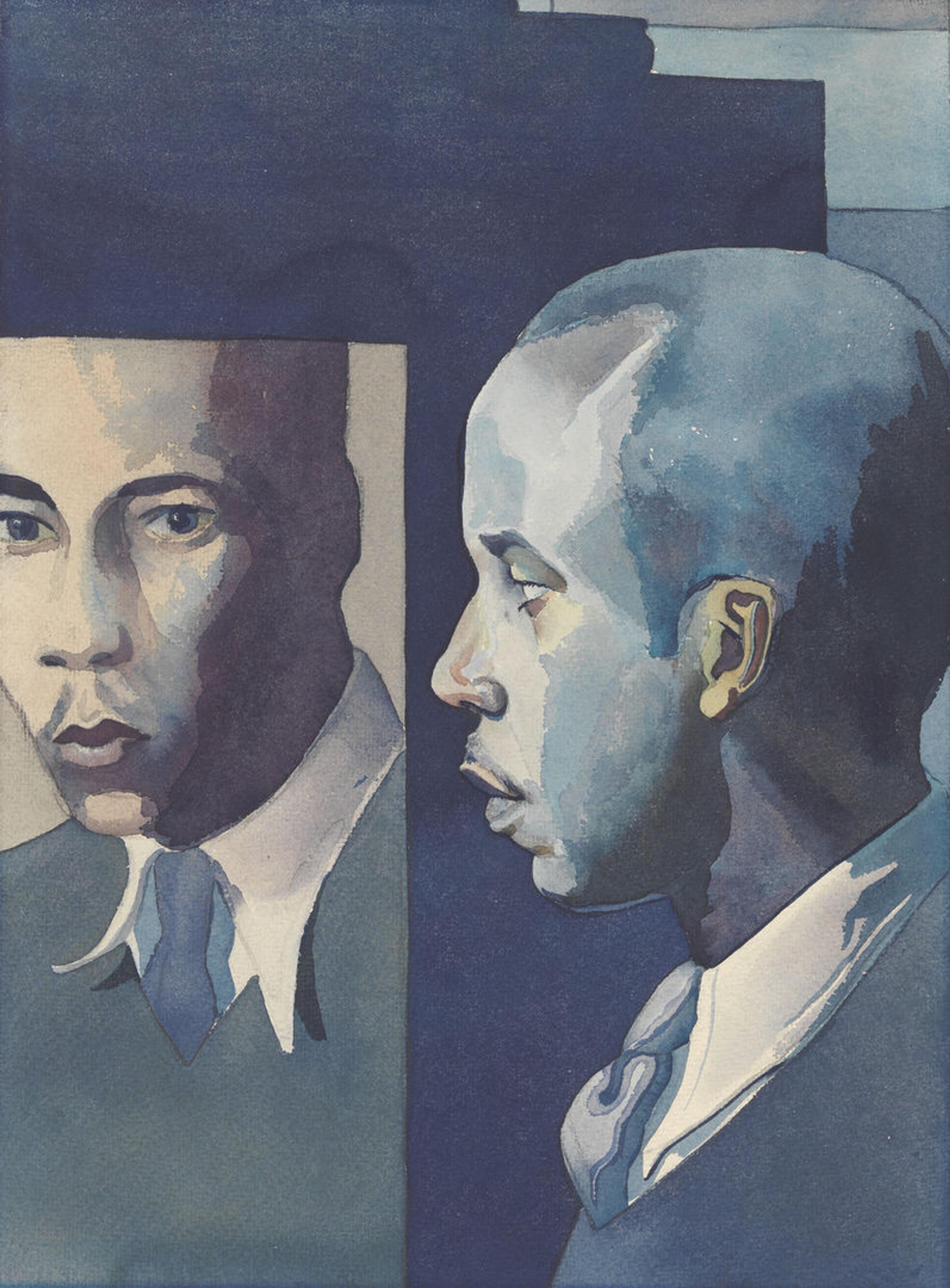

LYNNE: There’s a painting Denise included in the exhibition by Samuel Joseph Brown, Jr. It’s a self-portrait in watercolor and it speaks to Du Bois’s idea about the value of art and what it can communicate.

Samuel Joseph Brown, Jr. (American, 1907–1994), Self-Portrait, ca. 1941. Watercolor, charcoal, and graphite on paper, 20 1/4 x 15 3/8 in. (51.4 x 39.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Gift of Pennsylvania W. P. A., 1943 (43.46.4)

LYNNE: There’s a sense of melancholy in this painting. In tones of blue and gray, a man is looking at his reflection in a mirror. You can find a link to the painting in the episode description.

MURRELL: Samuel Joseph Brown’s Self-Portrait is an example of a work that really represents some of the core ideas of the New Negro Movement, but that was kind of lost to art history. And I specifically remember coming across this… I’ve never seen it before! It’s been in The Met’s collection since the 1940s. I look at this and I immediately think about W. E. B. Du Bois, the double consciousness.

LYNNE: Du Bois first introduced this idea of double consciousness in his foundational work, The Souls of Black Folk, in 1903.

MURRELL: Always conscious of, on the one hand, looking at oneself, attempting to develop one’s own authentic mode of self-expression, self-representation. But always conscious of being defined by the external gaze of the majority White population. And that is a racialized gaze.

LYNNE: And that’s a gaze that exists alongside segregation in the South and institutional racism in the North.

MURRELL: And when you look at this, you see that it is a representation of the artist looking at himself, but it’s not an exact representation. The perspective is off, it’s asymmetrical. And I think that captures and invokes some of the non-naturalistic aesthetics that define modern art of the period. It also captures the psyche of always feeling just slightly off-balance. Not being fully not able to fully articulate one’s existence in the way that one would choose.

LYNNE: He was a strong proponent of respectability politics: putting your best foot forward in society and becoming a leader in your community, even if it means pandering to the taste and values of a White elite.

Locke studied philosophy at Harvard and was the first Black person to receive a Rhodes Scholarship to study at Oxford. He graduated well aware of how to navigate within White institutions. But Locke’s aesthetic moved away from propaganda and towards an embracing of the Black artists of the Harlem Renaissances’ relevance in the larger art world.

Regardless of the means to achieve it, they both strived towards a shared goal.

MURRELL: They both were absolutely committed to the idea of authentic Black self-expression, autonomous of White oversight and regulation, both in the written word and in works of art, period: literature, music, painting, sculpture, photography.

So, I think it was a shared commitment to modernizing the Black image, even though they had sometimes divergent styles, approaches to aesthetics, and modes of expression.

LYNNE: This idea of modernizing Black artists in America started to gain traction in Harlem. Like a lot of great stories, it starts at a dinner party.

MONICA L. MILLER: So, this dinner party took place on March 21, 1924, at the Civic Club.

LYNNE: This is Monica L. Miller, she’s a professor of English and Africana studies at Barnard College, Columbia University.

MILLER: What was important about that dinner party is that it brought together this sort of emerging sort of Negro intelligentsia with publishers and also philanthropists. So, this was a party that was designed in some ways to start the Harlem Renaissance.

At that party, Alain Locke and Du Bois and James Weldon Johnson and a couple of other sort of old guard sort of African American activists and “race men,” as they were called at the time. They were there interacting with a sort of younger group of of African American Negro artists.

And the evening was such a success that by the end of the evening, Alain Locke was charged with putting together an anthology of the work of the people who were in the room.

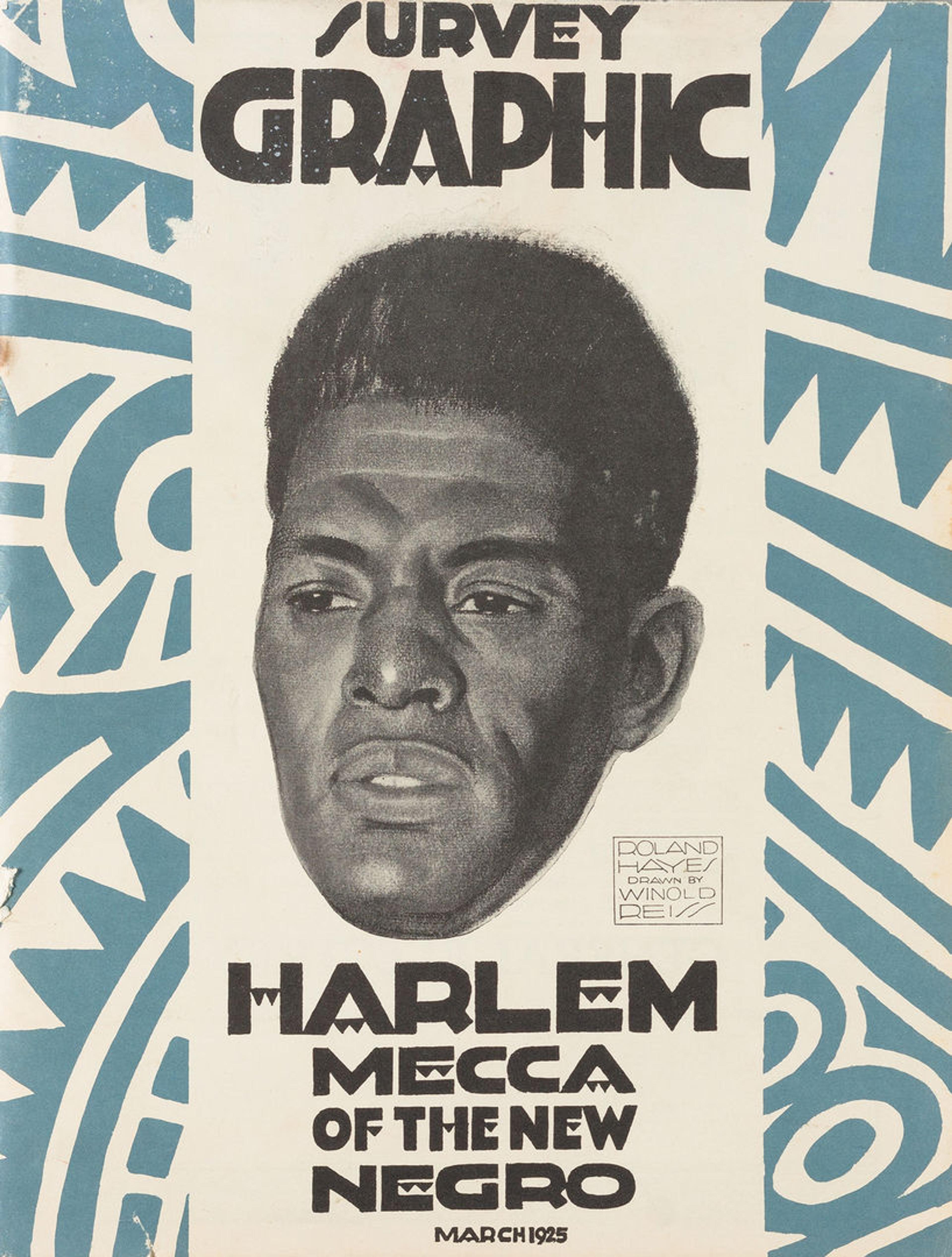

LYNNE: This was a special edition of the Survey Graphic magazine titled “Harlem, Mecca of the New Negro.” It was an instant success.

Winold Reiss (American, born Germany, 1886–1953), Roland Hayes, cover of Survey Graphic (March 1925), edited by Alain Locke (“Harlem: Mecca of the New Negro”). Thomas J. Watson Library, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

MILLER: As soon as it came out, people were just buying it in droves. It was incredibly popular both within the African American community, as well as sort of more educated, and to a certain extent, sympathetic White readers.

LYNNE: The cover of this edition of the Survey Graphic is by the White German-born artist Winold Reiss.

Contributions to the publication came from both Du Bois and Locke themselves, and provided a platform for the movement’s other major thinkers, like Arturo Schomburg, James Weldon Johnson, and Langston Hughes.

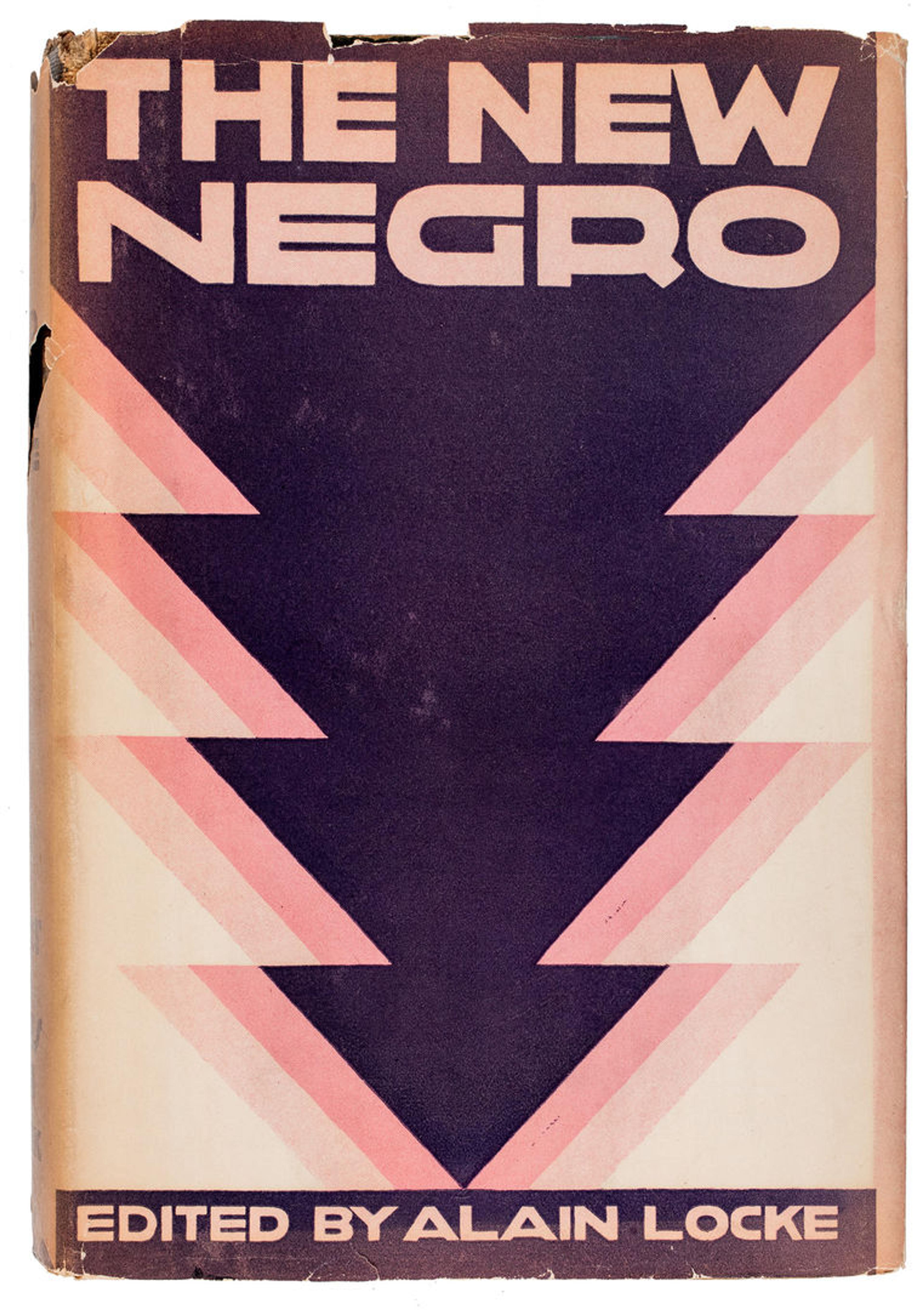

MILLER: On the success of that, Alain Locke was encouraged to expand the Survey Graphic into The New Negro anthology. And that volume includes, I’m going to say, nearly all of the of the most prominent writers of the Renaissance, as well as essays from some philanthropists and also other academics who were really concerned with the sort of Negro cause at the time.

Alain Locke (American, 1885–1954). The New Negro, 1925. Collection of Walter O. And Linda Evans.

MILLER: It includes essays, poetry, drama, artwork. The essays are both about African American life in addition to being about Afro-diasporic community. So, the volume really includes many of the writers, many of the perspectives, and really is designed to sort of be the actuality and a metaphor for the ambition of the African American community at that time.

It is an announcement that African Americans were on the American cultural scene and that they were cosmopolitan and connected. It was an announcement both to other people, as well as to the community internally.

LYNNE: Winold Reiss was a skilled illustrator and painted some of the most iconic portraits of the movement’s most famous faces. The Survey Graphicwas so popular it had to be bound as an anthology. Reiss, alongside his mentee Aaron Douglas, illustrated The New Negro for wider distribution, solidifying its place in history.

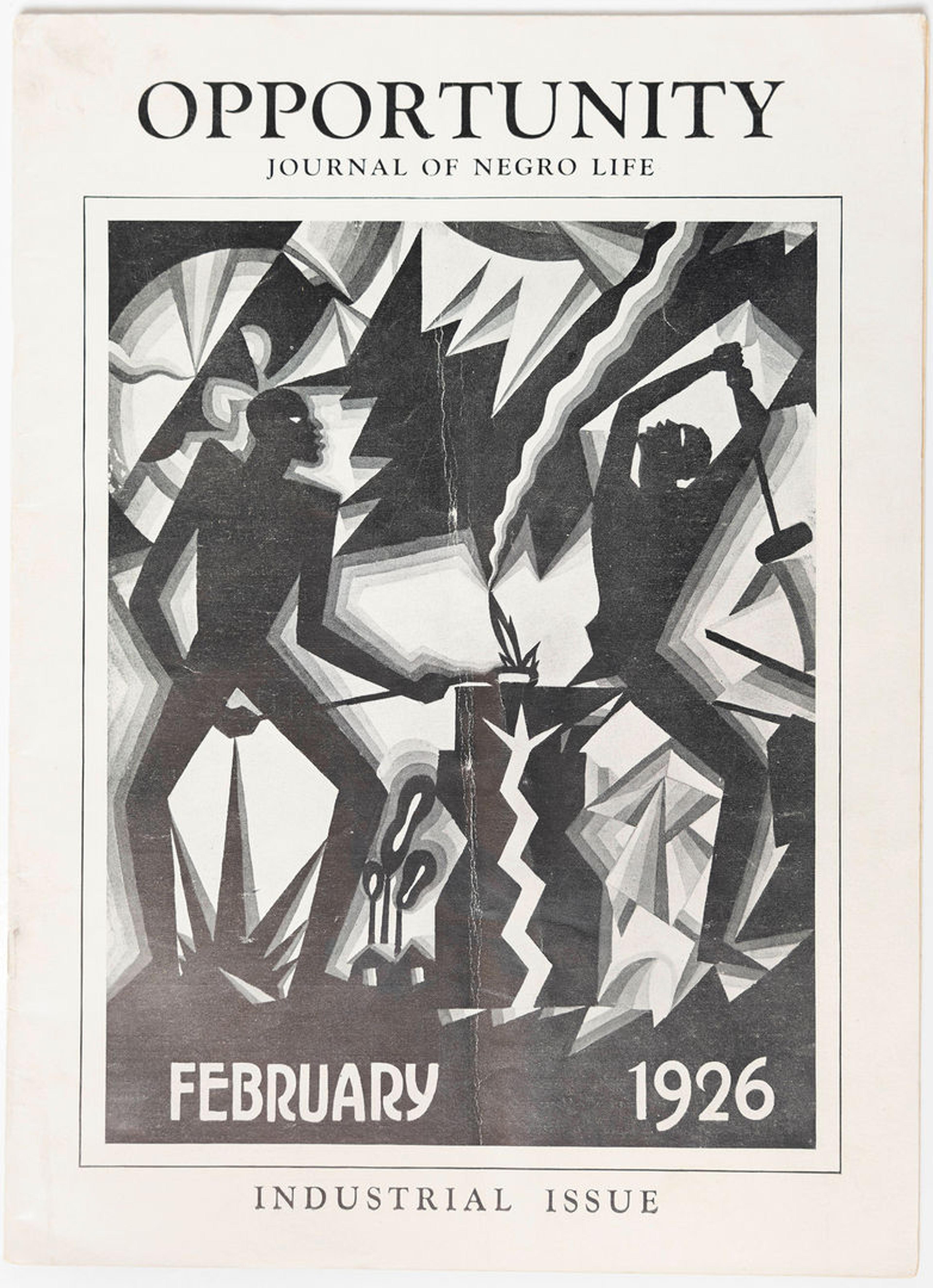

POWELL: Aaron Douglas was a really important artist working in Harlem in the 1920s and part of the 1930s. He was kind of the go-to artist for all of the great writers during this time period. He illustrated books for Carl Van Vechten, for Langston Hughes, for James Weldon Johnson. And his imagery, I would say, in that way, is in response to the poetry, to the prose, to the narratives that these writers are exploring. And there’s also a kind of interactivity when we see his images

Aaron Douglas (American, 1899– 1979), cover of Opportunity 4, no. 38 (February 1926) (“Industrial Issue”). Collection of Walter O. and Linda Evans

POWELL: They are very abstract. They’re very stylized figures that almost remind you of zigzags and patterns. The legs are bent, the arms are akimbo, the necks are turned.

LYNNE: Aaron Douglas was born in Topeka, Kansas, but moved to Harlem in the 1920s. After illustrating the anthologyThe New Negro, his graphic work, paintings, and murals became a study of a people and their history. Here’s scholar and curator Bridget R. Cooks.

COOKS: His focus really was on the journey from the African homeland to the 1930s as a modern Black community in the United States. There was the story that he wanted to tell that showed both struggle and triumph. It focuses on labor, it focuses on possibility, and it focuses on tragedy and this kind of fullness of a story, right? The story that all communities have of struggles, strife, and then opportunities and successes, you know. To move onto a kind of progressive narrative to think about what’s next.

Those are things that I believe Aaron Douglas really wanted people to understand in order to appreciate the Black people that existed at that time that they needed to re-understand, or relearn, or maybe learn for the first time the complexity of the history of African American people.

MILLER: He’s really well known for his mural that is at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, which traces the history of African Americans from slavery through freedom to the modern era. And his work has become a kind of visual signature of the Harlem Renaissance.

Aaron Douglas (American, 1899–1979), Aspects of Negro Life: From Slavery to Reconstruction, 1934. Oil on canvas, 60 in. x 11 ft. 11 in. (152.4 x 363.2 cm). Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Art and Artifacts Division, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations (PA.34.001.3)

LYNNE: Douglas’s mural has four panels and is titled Aspects of Negro Life. This panel—From Slavery to Reconstruction—can be seen in The Met’s exhibition.

MILLER: One of the things that’s incredible about Aaron Douglas’s work is the way that it layers history and culture in the paintings. The main figure is a man who is surrounded by dancing folks and musicians. And there’s this incredible energy in the middle of the painting. But we also see behind this man like a series of concentric circles, which are both the sun, right, but that also are sort of bringing out other, it seems like, layers of history, right, behind this group of people who look a little African. They look a little modern, right?

So, there’s a way in which like time and space here are really the time and space of African American history and culture are all being depicted in this one painting. It’s just such a summary, and a joyous summary. Like, there’s energy and joy in this painting that when I look into it, I feel like I’m looking into the past, but I’m also also seeing the future.

LYNNE: Keep in mind this idea of the New Negro was not confined to Harlem. Even now, more than a hundred years later, it’s crucial to not reduce the impact of these incredible Black artists to their race. The work being made during this period had the same amount of import and insight to a larger conversation in modernity as any other work being made at the time.

POWELL: When I think of the Harlem Renaissance, it’s always important to remember that term is a term that is both specific and it is metaphorical. It’s specific in terms of the Black community in New York, but it’s metaphorical in the sense that this desire for a kind of a Black modernism is happening in Chicago, it’s happening in Washington, it’s happening in Paris, it’s happening in Havana, it’s happening in Port au Prince.

—

LYNNE: During this time major art institutions were either unwilling or unaware of the significance of this work to establish serious permanent collections. So, the collections of Historically Black Colleges and Universities would become safe havens for the Black art of the Harlem Renaissance.

MARY SCHMIDT CAMPBELL: The role of HBCUs is absolutely critical to the Harlem Renaissance.

LYNNE: That’s Mary Schmidt Campbell.

CAMPBELL: I am the president emerita of Spelman College. Before that, I was the director and chief curator at the Studio Museum in Harlem.

From the time that Alain Locke published his essay on the New Negro to up to, let’s say, World War II, overwhelmingly, most American museums simply were not collecting the work of African American artists.

LYNNE: Of course, there were places you could see Black art such as the Baltimore Museum and the Newark Museum.

CAMPBELL: And of course the Jacob Lawrence Migration Series that went to both the Museum of Modern Art as well as the Phillips Collection. But that’s a really small portion of the work that was produced by these artists.

So, the collections that were amassed by Historically Black Colleges and Universities become absolutely critical because they had become, by default, the principal collectors of the works of African American artists.

LYNNE: Many leading figures and artists of the Harlem Renaissance were passionate about education. Some were educators while still being practicing artists.

CAMPBELL: And many of the artists whom we recognized as major artists in the Harlem Renaissance… I wouldn’t say many, but several of them were faculty members. So, Aaron Douglas went to Fisk and was a distinguished professor at Fisk for many years. Hale Woodruff started the art department at the Atlanta University Center Consortium, and was an absolute leading figure in Atlanta for many years.

LYNNE: Denise, as the curator of the The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism, faced some challenges in finding the work and in restoring important pieces to ensure that they were ready for display.

MURRELL: So, visiting the campuses and seeing the work in storage, and then having to do various degrees of conservation to make it gallery-ready, that’s certainly one challenge. But I think it has also been a fabulous opportunity because now that we know this body of work and we have established contacts, working relationships with the four HBCUs— Howard, Fisk, Clark Atlanta University, and Hampton University—I feel that we will have ongoing partnerships with those institutions and hopefully other large museums will, as well. And that this project will help bring more attention to that body of work.

COOKS: There are new people, new generations of people that are discovering the art of the Harlem Renaissance for the first time and are often really frustrated that they didn’t know about it until that moment.

LYNNE: This is Bridget R. Cooks, again.

COOKS: It’s proof that we have to sustain and persist in making sure that the visibility of the contributions of African American artists are always part of American art history and American art museums and galleries.

The museum has been an exclusive place and really just an elitist place in terms of defining what is beautiful, what objects are valuable, which stories are important to be told. There has to be a process of making room for people who have been told that they don’t belong in the museum space.

There has to be a component, really, of social practice and engaging with communities in ways that are not extractive, but that are collaborative. And in that way, we think that, not only the art that the museum buys, the art that the museum exhibits will change, but also, the understanding of the value of those people, those histories, and those systems will also be reflected in programing and in wall labels.

There are plenty of ways in which American institutions can show the objects that they currently have, even if they weren’t made by a diverse group of people, to tell a story that accounts for a more accurate history of colonization, exploitation, genocide, conflict, and even hope for the future.

LYNNE: The Harlem Renaissance was a convergence of people from different places, with different talents all working to modernize how they were represented in the larger American story. And we are going to get into the ways they did that.

From the Black Americans working to represent themselves and the spaces they walked into through fashion…

ROBIN GIVHAN: If you are someone you know for whom society has determined that you have to fit into a particular box or a particular category, being able to use fashion to express who you are is extraordinarily powerful.

LYNNE: To the places that they socialized and the sounds they heard while they did it…

CHRISTIAN MCBRIDE: Sitting down and listening to extended improvisational jazz, that wasn’t really quite the case, at that time. It was all about dancing.

LYNNE: To the words and images they were putting down on the page, documenting their experiences, their dreams, their imaginations, wondering what could be…

JOHN KEENE: The writers ofFire!! were not concerned with presenting neat bourgeois representations of Black people.

LYNNE: The Harlem Renaissance was a period of extraordinary creativity and intellectual discovery that continues to resonate today. I’m so excited to dive into all the ways that Harlem... is everywhere.

—

Harlem Is Everywhere is produced by The Metropolitan Museum of Art in collaboration with Audacy’s Pineapple Street Studios.

Our senior producer is Stephen Key.

Our producer is Maria Robins-Somerville.

Our editor is Josh Gwynn.

Additional production in this episode by Jonathan Menjivar.

Mixing by our senior engineer, Marina Paiz.

Additional engineering by our senior audio engineer, Pedro Alvira.

Our assistant engineers are Sharon Bardales and Jade Brooks.

I’m your host, Jessica Lynne.

Fact checking by Maggie Duffy.

Legal services by Kristel Tupja.

Original music by Austin Fisher and Epidemic Sound.

The Met’s production staff includes producer, Rachel Smith; managing producer, Christopher Alessandrini; and executive producer, Sarah Wambold.

This show would not be possible without Denise Murrell, the Merryl H. & James S. Tisch Curator at Large and curator for The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism exhibition; and research associate is Tiarra Brown.

Special thanks to Inka Drögemüller, Douglas Hegley, Skyla Choi, Isabella Garces, David Raymond, Ashliy Sabb, Tess Solot-Kehl, Gretchen Scott, and Frank Mondragon.

Asha Saluja and Je-Anne Berry are executive producers at Pineapple Street.

Support for this podcast is provided by Bloomberg Philanthropies.

Episode two is out now. Tune in to hear from fashion reporter Robin Givhan and scholar and curator Bridget R. Cooks about the fashion of the Harlem Renaissance

###