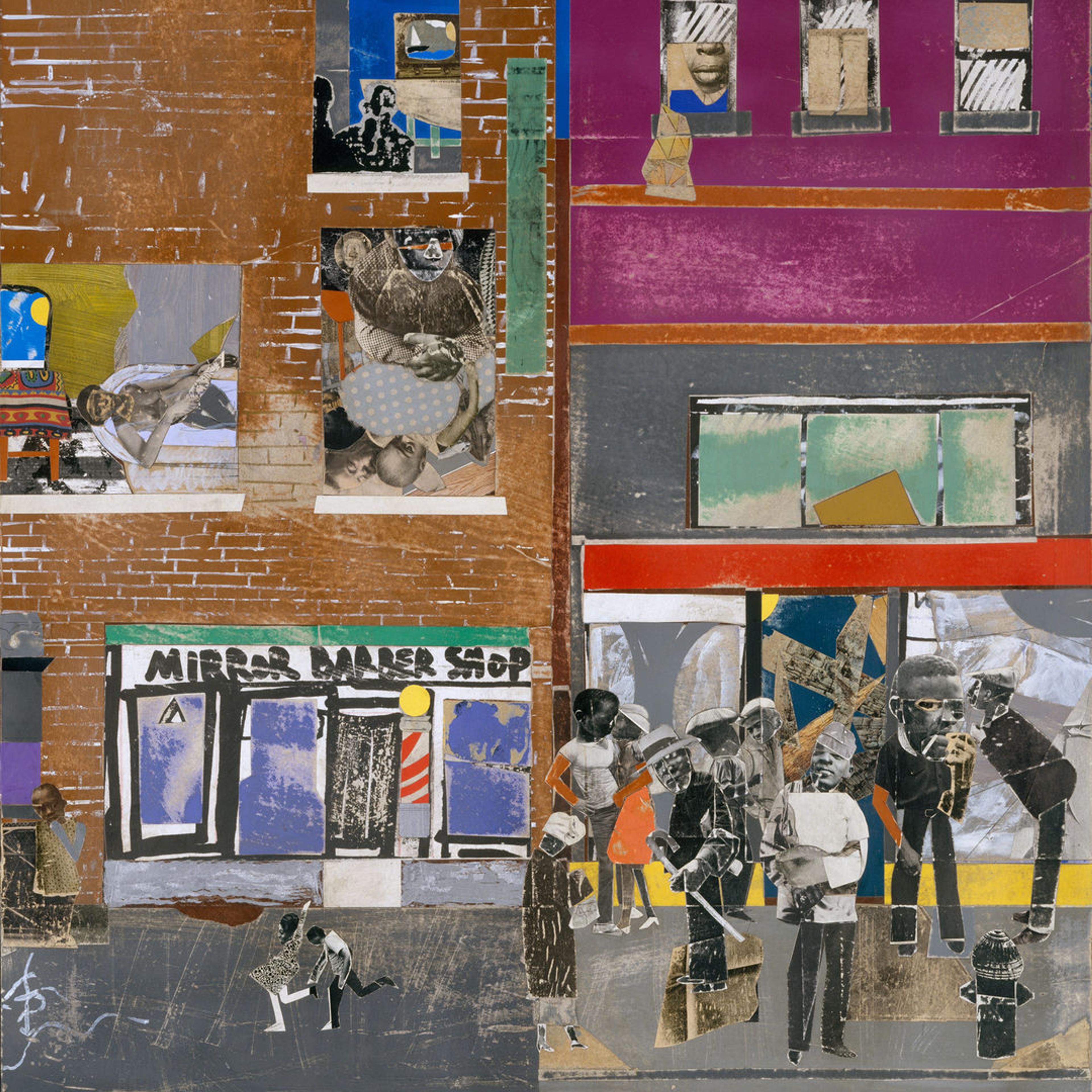

A streetscape of Harlem assembled from paper, Romare Bearden’s monumental collage The Block (1971) imagines a vibrant panorama of city life. Residents congregate outside their apartment buildings. Pallbearers carry a coffin to a waiting hearse while the spirit of the deceased is received by angels. A new mother cradles her baby. A barbershop, Baptist church, and liquor store line the street level, while the private lives of the neighborhood’s inhabitants are revealed in the interiors above. The artist based the architecture of The Block on a stretch of Lenox Avenue between 132nd and 133rd Streets, though the location and activity depicted are meant to represent a typical Harlem scene.

Romare Bearden (American, Charlotte, North Carolina 1911–1988 New York). The Block, 1971. Cut and pasted printed, colored and metallic papers, photostats, graphite, ink marker, gouache, watercolor, and ink on Masonite. 48 in. × 18 ft. (121.9 × 548.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Samuel Shore, 1978 (1978.61.1-.6) © 2024, Romare Bearden Foundation / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Bearden produced his collage as six separate panels, exhibited together to form a continuous scene. The panorama takes on a cinematic quality, as fugitive moments unfold across each section. It evokes not just the sights, but also the sounds of Harlem—from the traffic on the street corner to the televisions blaring from open windows. Bearden himself once referred to The Block as a “collage with sound.”[1] When the mural-sized work debuted at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in Bearden’s 1971 retrospective Romare Bearden: The Prevalence of Ritual, it was shown as the triumphant finale to the exhibition in a gallery of its own.

Hardly remarked upon in literature on the work, however, is the audio-tape collage that accompanied The Block on its first showing. Commissioned by the exhibition curator Carroll Greene Jr. and produced by an external contractor with the artist’s consent, the soundtrack animates Bearden’s visual narrative with corresponding audio clips. The Metropolitan Museum of Art acquired Bearden’s artwork as a gift in 1978 and received the accompanying soundtrack as a constitutive element of this piece. But the tape was subsequently lost, and the collage has not been exhibited again with its soundtrack since 1971. The recent rediscovery of the tape in the MoMA archives allows for a new consideration of The Block alongside its audio element for the first time in more than fifty years, inviting a politicized interpretation of the work and illuminating the context of its initial display.

The Prevalence of Ritual was Bearden’s first museum retrospective, surveying his collages, works on paper, and large-scale photo enlargements from 1941 to 1970; Bearden made The Block specifically for the occasion. During the planning of the exhibition, Greene had the idea to commission a soundtrack to accompany the collage. Today this might seem like a significant overreach of curatorial responsibility, in that it would fundamentally transform the work and its reception. In a memo dated October 28, 1970, Greene wrote to curatorial assistant April Kingsley: “I propose the inclusion of taped music, probably muted jazz, with a strong overlay of street sounds and noises, i.e., the sound of automobiles, footsteps, laughter, talking etc., and the general cacophony characteristic of the area. Ideally, these sounds should be recorded in the area of 133rd Street and Lenox Avenue.”[2]

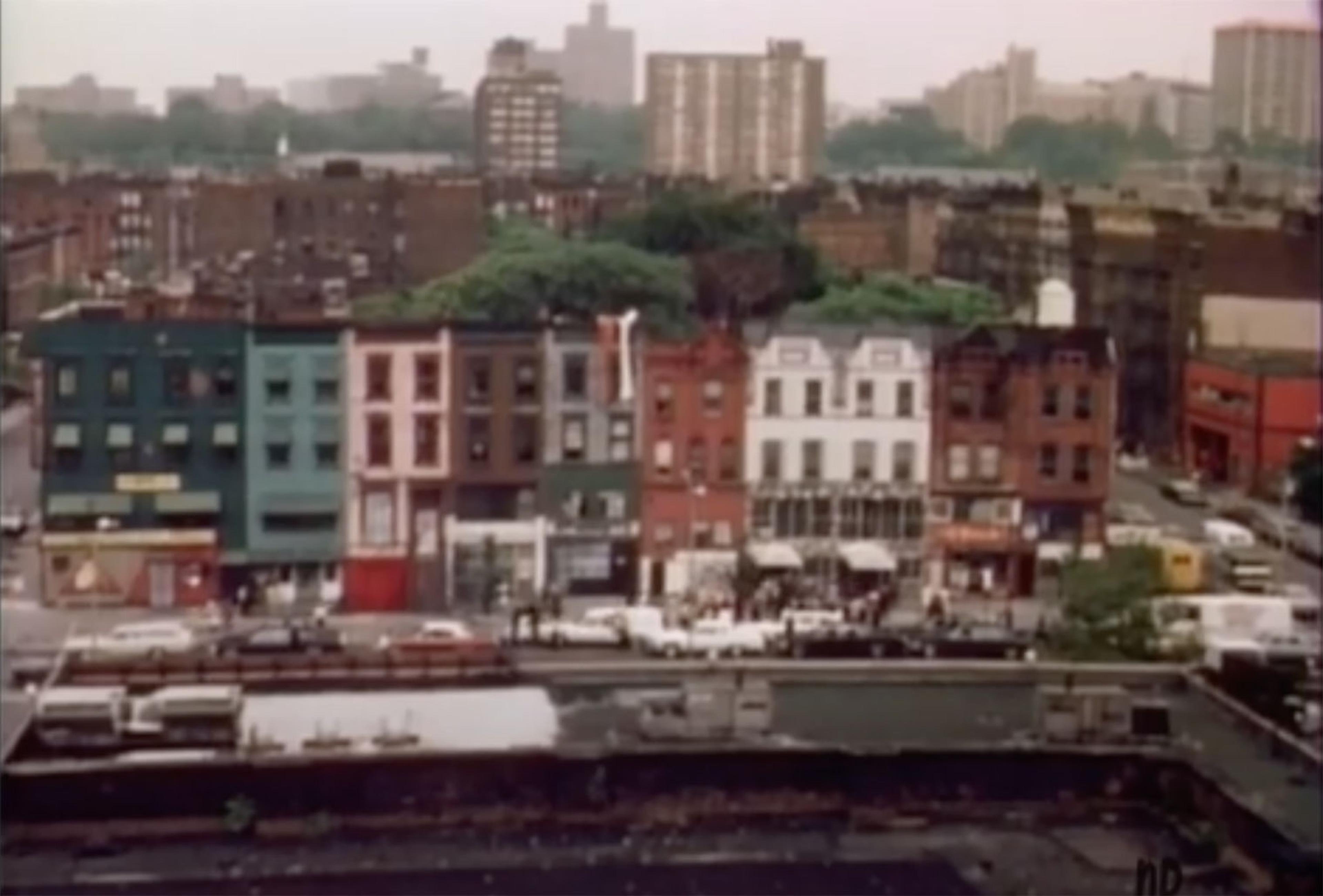

Video still from Bearden Plays Bearden (1984), dir. Nelson E. Breen. Courtesy PBS

It is unclear whether Greene consulted Bearden, or if the artist was involved at all in the production of the soundtrack. A memo in the archives at MoMA written by Kingsley during Bearden’s retrospective notes “a taped collage of street sounds, which the artist is presently constructing,” though there is no other evidence to indicate that Bearden participated in its recording or manufacture.[3] Yet the artist at least allowed, if not sanctioned, the production and exhibition of a soundtrack for The Block, what amounts to tacit consent for the curator to add an element to the work that would shape its response. A photograph of Bearden at MoMA shows him seated proudly before the panels; the equipment and speakers for the soundtrack are mounted out of sight so as to highlight the audio track rather than the technical system.

Romare Bearden in front of The Block, 1971, as shown at the Museum of Modern Art in Romare Bearden: The Prevalence of Ritual. Museum of Modern Art Archives, Museum-Related Photos, 71.

Greene commissioned sound designer Daniel Dembrosky of Shorewood Publishers to craft an original audio collage to his specifications. A document authored by Dembrosky and submitted during the show’s organization summarizes the sound effects and field recordings to be used in the audio piece including soul music, street noise, televisions blaring news of war, an electric razor, a couple making love, a Sunday Baptist church service, singing voices, conversation, crying, kids playing, and a rat trap. At Greene’s request, Dembrosky later added jazz played by street musicians, which opens and closes the nearly eight-minute recording.

The Sounds of The Block

“The Block,” produced by Daniel Dembrosky and Romare Bearden, 1971. Museum of Modern Art Archives, Sound Recordings, 71.28a. Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by Scala Group S.p.A., 2024.

The final soundtrack does not follow exactly the outline of sound effects submitted by Dembrosky. Rather, two English-language television news clips dominate the recording. A report on heavy casualties in the Vietnam War, layered with the sound of artillery fire, immediately precedes a newscast about a house fire caused by arson that threatened the lives of hundreds of women and children at an unspecified location. The reporters’ voices are clear and legible, rising above the chatter and street sounds that characterize the rest of the recording. These audio reports on tragedies, both foreign and domestic, compel a different interpretation of The Block than the one offered strictly in visual terms. Instead the work becomes a racialized indictment of the sociopolitical circumstances that afflicted Black communities in 1971, from the disproportionate number of African American combat troops in Vietnam to the burning buildings that contributed to Harlem’s decline in the 1970s, forcing many residents to leave the neighborhood.

Greene’s selection of Dembrosky could not have been a coincidence. While still on view at MoMA, the collage was purchased by Shorewood Publishers, a New York City–based company that produced album covers and packaging for the music industry, headquartered near MoMA at 724 Fifth Avenue. That the soundtrack for The Block originated from the work’s eventual owner provides necessary context. The audio collage may not have been an attempt to provide a sonic illustration of Bearden's work, with audio clips edited together to generate a background track subordinate to the picture, but rather a vehicle for expressing the owner’s own perspective on Harlem and its inhabitants.

Two details of The Block

After closing at MoMA, The Prevalence of Ritual toured six other venues around the United States, ending its run, fittingly, at the Studio Museum in Harlem on September 30, 1972. According to correspondence in MoMA’s archive, The Block toured with the accompanying audio piece to at least some, if not all, of these venues, though it is unclear if they were ultimately exhibited together.[4] Yet by this point, it is clear that they were considered a pair: the checklist for The Block in the exhibition catalogue lists “collage of paper and synthetic polymer paint on composition board, with a pre-recorded tape of street sounds, church music, blues, laughing voices, and the sounds of children at play provided by Daniel Dembrosky.”[5] Critics of the retrospective largely derided the work as overly literal. One complained, “The treatment is too decorative, the vision too serene, the color too cheerful.”[6] The soundtrack barely receives any mention. Little information exists to confirm Bearden’s own feelings, although a 1977 profile on the artist by Calvin Tomkins claims that the artist felt, by that point, the audio “was not a good idea” because “the painting needs no accompaniment.”[7]

When visionary curator Lowery Stokes Sims acquired the artwork for The Met in 1978, it arrived with the soundtrack, according to the intake paperwork. Sometime soon after, the tape vanished under unknown circumstances; subsequent displays of the massive collage at The Met and elsewhere included only the paper, but not the audio collage. Thereafter, the recording largely disappears from the historical record. Contemporary discussions of the work contain only brief references to the soundtrack, passing it off as nonintegral to the piece. A 1995 publication about The Block produced by The Met “gives us the sounds” of the collage through new poems on the artwork by Langston Hughes, though the soundtrack goes curiously unnoted.[8]

Detail from The Block

Considering once again this lost audio file and the circumstances of its production offers a chance to reappraise The Block. While the montage contains sound clips that correspond to Bearden's narrative panorama, its emphasis on distressing television news coverage outweighs the compositional significance of the single television monitor in the collage and even conflicts with its visual depiction: a screen displaying a sailboat under sunny skies. While we cannot know if Bearden intended his work to be read as a subtle sociopolitical critique of the moment, he certainly allowed for this interpretation. The soundtrack imputes overt politicized meaning to The Block, announcing both the external forces (war, prejudice, government) that transformed Black communities during the 1970s and a museum curator’s influence on a work of art and its reception.

Acknowledgment

The author thanks Randall Griffey and also Mary Schmidt Campbell for sharing her memories of Bearden.

Notes

[1] Romare Bearden, quoted in an advanced fact sheet for the exhibition Romare Bearden: The Prevalence of Ritual, Museum of Modern Art Archives, 958.3.

[2] Carroll Greene, Jr., first draft of exhibition fact sheet for Romare Bearden: The Prevalence of Ritual, Museum of Modern Art Archives, 958.11.

[3] April Kingsley, exhibition summary for Romare Bearden: The Prevalence of Ritual, Museum of Modern Art Archives, 958.18.

[4] The other venues were the National Collection of Fine Arts, Washington D.C.; Art Museum, University of California, Berkeley; Pasadena Art Museum, California; High Museum of Art, Atlanta, Georgia; North Carolina Museum of Art; and the Studio Museum in Harlem.

[5] Carroll Greene Jr., Romare Bearden: The Prevalence of Ritual. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1971, p. 20.

[6] Charles Allen, “‘Have the Walls Come Tumbling Down?’” New York Times, April 11, 1971, p. D28.

[7] Calvin Tomkins, “Putting Something Over Something Else,” New Yorker, November 28, 1977, p. 75.

[8] Langston Hughes, The Block. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1995.