What was the political legacy of the Harlem Renaissance? In the final episode, we’ll explore the lasting impact of the art and organizing that happened during the 1920s and ’30s and how it paved the way for the civil rights movement. We’ll highlight some key political events of the time and explore the work of artists such as Romare Bearden and Augusta Savage. We’ll also touch upon what it means for The Met to tell this story in 2024, more than fifty years after its controversial exhibition Harlem on My Mind.

Follow Harlem Is Everywhere wherever you listen to podcasts:

Listen on Apple Podcasts | Listen on Spotify | Listen on YouTube | Listen on Amazon Music

Visit The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism through July 28.

Supported by

Transcript

JESSICA LYNNE: Welcome to Harlem Is Everywhere, brought to you by The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

I’m your host, Jessica Lynne. I’m a writer and art critic. This is episode five: Art as Activism.

In this podcast we’ve spoken about how as a result of the Great Migration, Black people came together and created some of the most enduring art of the twentieth century. In this episode, we’ll explore how the art and culture of the Renaissance laid the groundwork for thinking and organizing in the civil rights movement.

In his groundbreaking essay “The New Negro,” Alain Locke wrote, “Art must discover and reveal the beauty which prejudice and caricature have obscured and overlaid… All vital art discovers beauty and opens our eyes to beauty that previously we could not see.”

The Harlem Renaissance created a lasting impact on communities far beyond the streets of Harlem. The movement promoted self-expression, dignity, and a new social consciousness.

We’ll speak with renowned curator, writer, and historian Mary Schmidt Campbell.

MARY SCHMIDT CAMPBELL: This notion that we can organize around a very specific goal that we’re trying to achieve really blossomed during the Harlem Renaissance. And then it just, I must say, exploded and became a national focus during the civil rights movement.

LYNNE: We’ll also speak with artist Jordan Casteel.

JORDAN CASTEEL: It was really about a mass population saying, we’ll no longer stand for this, and reaching across barriers in order to get that done.

LYNNE: And curator of The Met’s exhibition The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism, Denise Murrell.

DENISE MURRELL: There was a willingness to be independent, to be autonomous, and to express one’s authentic self. And those factors that change in the psyche of the African American I think is part of what enabled the emergence of the full-blown civil rights movement in the fifties.

—

LYNNE: The many artists who wrote, painted, sculpted, danced, composed, and designed in the time now known as the Harlem Renaissance were part of a culture-defining zeitgeist. They lived, worked, and played in a neighborhood that shaped them as much as they shaped it.

In so many ways, the Harlem that I’ve come to know and love emerged during this period of artistic output. Its position in the world as a Black mecca is the result of many diverse, beautiful minds coming together. Sometimes in disagreement, but mostly in love, to celebrate the complexity of Black life and to imagine an even better future.

I think a young person who encounters stories about Langston Hughes, Aaron Douglas, Jessie Redmon Fauset, or Gladys Bentley one hundred years from now will encounter the stories of people who transformed our world. They forged new modes of expression by expanding what was possible to communicate with art and, in turn, they created new ways of living.

It makes me excited to think about someone finding an old copy of Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God in the year 2124 and deciding to tell a story about love, home, and belonging, inspired by the boldness and musicality of Hurston’s prose.

One hundred years from now I hope that these artists—and all of their peers—will continue to be acknowledged as the creative forces they were. And I hope that Harlem, undergoing tremendous change today, will always be respected as a wellspring of Black ingenuity.

—

MURRELL: The Harlem Renaissance has been considered to end when the Great Depression began, so the late twenties, early thirties. But for our purposes, we continue to follow the artists who emerged in the twenties to look at their mature work in the thirties and forties.

LYNNE: As the curator of the exhibition The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism, Denise Murrell wanted to reconsider the boundaries of this artistic movement.

MURRELL: It’s not like the artists and writers dropped dead in 1929, they continued to make work. Once the civil rights movement had begun, then they were addressing a different set of issues than they addressed before the civil rights movement kicked off in 1953, ’54.

LYNNE: The Harlem Renaissance helped lay the groundwork for the protests and demonstrations of the civil rights movement. One example of this is known as the Silent Protest Parade.

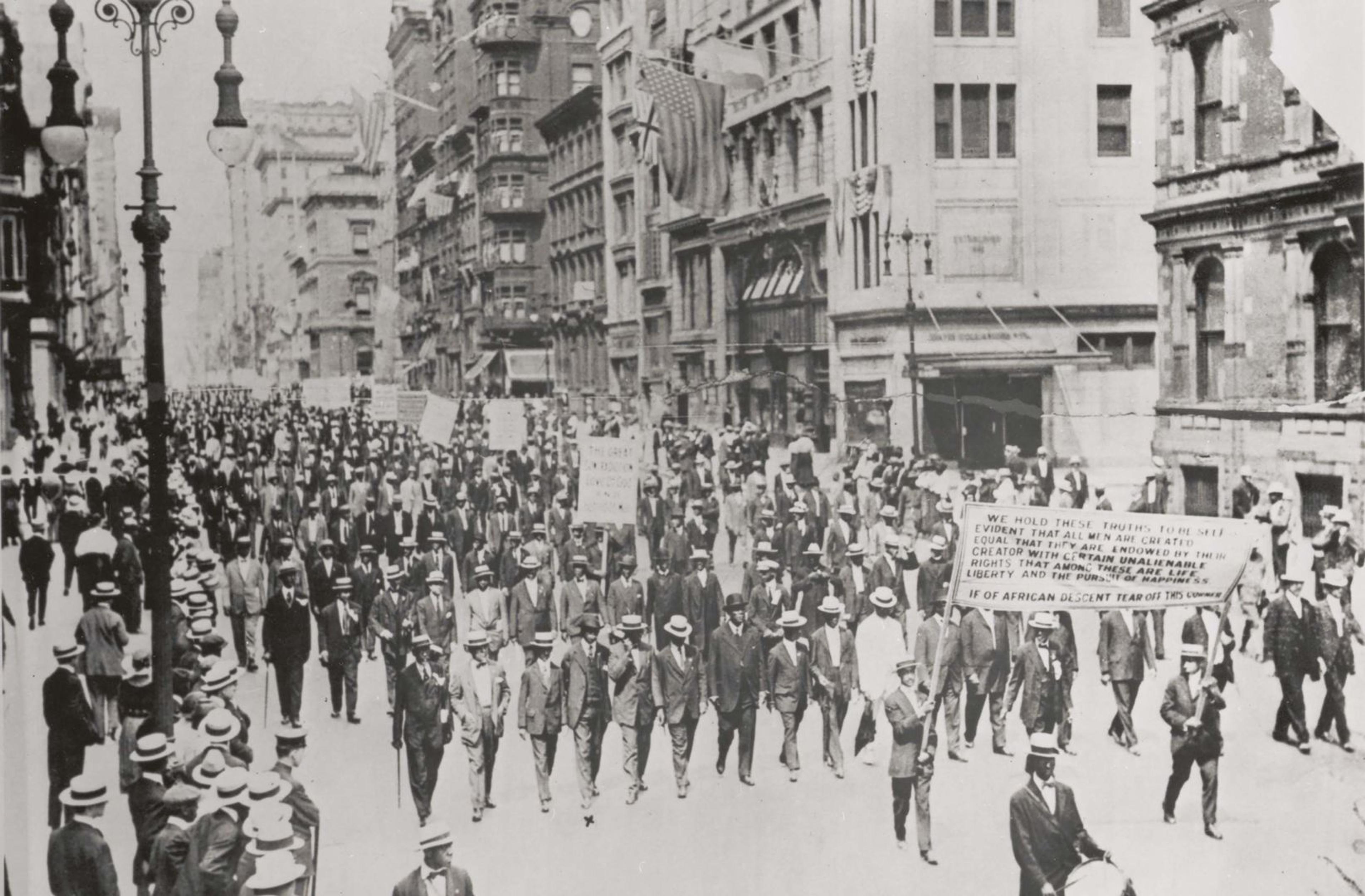

In July of 1917 a silent march was organized by the NAACP church and community leaders in response to lynchings and violence throughout the country. Here’s former president of Spelman College, Mary Schmidt Campbell.

Unknown artist, Silent Protest Parade on Fifth Avenue, New York, 1917. Gelatin silver print, 11 1/8 x 14 in. (28.3 x 35.6 cm). Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

CAMPBELL: The most dramatic, in 1917 was the silent protest where ten thousand African Americans—the women dressed in white, the men dressed in their suits and straw hats, along with children—marched silently down Fifth Avenue to the sound of muffled drums, holding placards with their grievances outlined. And there is some footage of that march that is absolutely extraordinary.

And when you think of what it took to organize all those people, get them dressed uniformly, have them show up at exactly the right time in formation and absolutely perfect marching format…. When you consider all of that that went into that, and the visual impact, the pageantry of all of that, it’s pretty extraordinary.

LYNNE: Some of those marching that day had most likely been part of the Great Migration, leaving the violence and racism of the South for safety in the northern cities. But the violence remained an ambient threat.

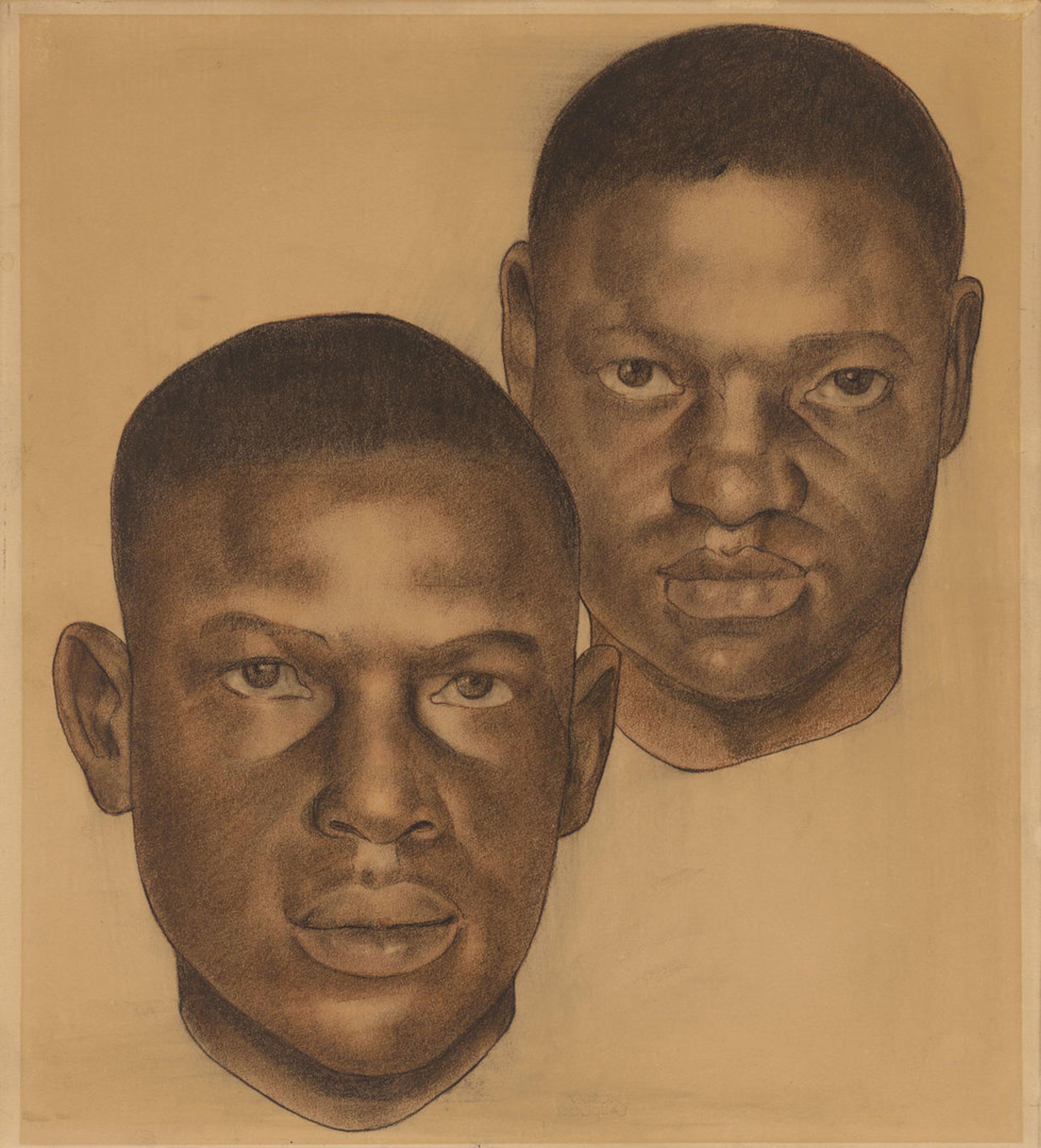

MURRELL: Someone who might be at the Savoy Ballroom one night gets on a train the next day in Washington, DC, has to get off and go back to the segregated cars. Getting off the train in someplace in North Carolina, South Carolina, Alabama, whatever, some episode with a White person. And that’s Emmett Till, that’s the Scottsboro Boys. There’s the ever present vulnerability and risk of that type of physical threat, life-threatening situations that all Black people of this period faced.

Aaron Douglas (American, 1899– 1979), Scottsboro Boys, ca. 1935. Pastel, 16 1/8 x 14 5/8 in. (41 x 37.1 cm). National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.; Conserved with funds from the Smithsonian Women’s Committee (2004.6)

LYNNE: The simple act of walking together took on an importance during this time that had a lasting impact. Similar to a jazz processional, these men and women, and in some cases boys and girls, could not be ignored.

Along with the NAACP’s Silent Protest Parade, the Harlem Hellfighters marched up Fifth Avenue with a homecoming parade from the First World War. Marcus Garvey hosted Universal Negro Improvement Association parades, which embodied the early twenties. There were also processions by organizations like the Freemasons and Elks.

Malvin Gray Johnson (American, 1896–1934), Elks Marching, 1934. Oil on canvas, 22 x 25 in. (55.9 x 63.5 cm). Amistad Research Center, New Orleans

There’s something extraordinary about these processions: seeing these communities in public, claiming their space.

Many practices from the Harlem Renaissance were utilized by activists of the civil rights movement. Using churches as places to gather and strategize. Coming together to demonstrate for a cause. Understanding the power of the Black vote and political activism.

As we’ve said before, nothing about this movement was monolithic. While many found the art, literature, and music of the time galvanizing, some activists and scholars of the next generation looked down on the Harlem Renaissance because they believed that its influence was superficial—that cultural change didn’t translate into political or material change.

But one thing is undeniable: the Harlem Renaissance showed generations to come that they deserved respect and dignity. That they were beautiful and capable. That they should be counted amongst the greatest artists of a generation. That together, they could change the world.

—

LYNNE: One artist featured in the exhibition who could be considered a link between the Harlem Renaissance and the civil rights movement is Romare Bearden.

Bearden’s family moved from South Carolina to Harlem during the Great Migration. His father was a musician and worked for the New York Health Department while his mother was a reporter for a prominent Black newspaper. Bearden’s house was a gathering place for figures of the Harlem Renaissance. He grew up surrounded by a generation of leaders and activists.

CAMPBELL: The political organizing in Harlem was phenomenal, and Bearden grew up right in the heart of that.

LYNNE: Here’s Mary Schmidt Campbell again. Mary would know—she was personal friends with Bearden and literally wrote the book on him: An American Odyssey: The Life and Work of Romare Bearden.

CAMPBELL: His mother had a salon in her living room. She would invite people like A. Philip Randolph and W. E. B. Du Bois and Marcus Garvey, who also was a huge organizer of the United Negro Improvement Association.

The organizational capacity was pretty extraordinary. And it showed up, as well, among the artists. Aaron Douglas and Augusta Savage were among the leaders who organized the Harlem Artist Guild.

LYNNE: These artists lobbied to get better access to government resources available through the Works Progress Administration so they could make murals and plan other public art commissions. They also made possible the Harlem Community Arts Center.

CAMPBELL: So, Bearden really grew up in an era when the artists had agency, when the artists had voice, when artists were taking things into their own hands.

LYNNE: It’s easy to think about movements like the Harlem Renaissance as something that just materialized out of thin air, a group of artists who all just happened to be creating at the same time. But one of the things that makes this movement so special is that it wasn’t passive. These artists, many of whom had just left all they knew in the South, were creating new lives and new opportunities for themselves and for the generations to come.

CAMPBELL: There was this incredible sense of not only self-determination, but sense of agency. And we’re not going to wait for someone to give us, we are going to make things happen.

That’s the environment in which he emerged as a young artist beginning to practice his craft. And I think understanding that environment gives you an understanding about him, about Jacob Lawrence, about Norman Lewis, about Roy DeCarava, all these extraordinary artists who came out of the Harlem Renaissance. But they came out of an environment that said, you have every right to claim your culture and to claim your right to be an artist.

LYNNE: Romare Bearden was a renaissance man. Playing semi-professional baseball, studying science and mathematics at Lincoln University before graduating from NYU with a degree in education. Then Bearden began gravitating towards art and became involved with the Art Students League. He lived an extraordinary life.

One of the final works in the exhibition is The Block. This piece consists of six separate panels that when shown together stretch to nearly eighteen feet long.

It’s a celebration of life in Harlem made with paint and collage materials.

Romare Bearden (American, 1911–1988), The Block, 1971. Cut-and-pasted printed, colored, and metallic papers, photostats, graphite, ink marker, gouache, watercolor, and ink on Masonite, 48 in. x 18 ft. (121.9 x 548.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Samuel Shore, 1978 (1978.61.1–.6)

CAMPBELL: When I first saw it at the Studio Museum in 1973, and I walked the length of this piece, you actually get the sensation that you are walking a block.

LYNNE: The neighborhood shown in The Block jumps out from a blue sky and gray sidewalks and streets. The buildings are violet, green, and brick—and bursting with energy.

This painting was inspired by a stretch of Lenox Avenue between 132nd and 133rd Streets. There’s a barbershop, a liquor store, a church.

CAMPBELL: And what I love about this piece is that Bearden has incorporated so many contradictions. So there’s very much the public life of a street. People outside of stores, people coming out of a funeral home, children gathering to play games, but it also pierces the exterior. So, we get a glimpse of private lives, of mother and child, of a couple making love, of someone simply gazing out of the window.

And so we have this counterpoint between public and private; between life and death. Honestly, there’s, you know, so much liveliness on the street, but then there’s a funeral procession there’s a representation of the belief of an afterlife. So, there are images of an angel and what look like a Madonna and child. But then, as I said there, people making love. So there is the sacred and profane. It really has this dynamic quality.

And all of this is captured in what he used to call rectangular structure. There is that very architectonic feeling of something that’s very orderly and managed. And then inscribed within that there is all this hustle and bustle of activity.

LYNNE: Collage is a fitting medium for representing Harlem. The Block captures the sense of the neighborhood as a mosaic of different personalities and types. So many voices from so many unique backgrounds coming together in one place.

Bearden became a master of collage. Clipping images from magazines, newspapers, and books. Blending aspects of Cubism and abstraction, almost quilting out images. Today Bearden is celebrated as one of the most treasured artists of his time.

CAMPBELL: When I was writing the book on Romie Bearden that was published in 2018, I went to The Met and asked to see the piece. And of course it is stored as it should be, each of the panels beneath glass.

But the woman who was in charge of this piece in the works on paper section allowed me to get down on my knees and look really closely at the materials. And, so, you see little pieces of string and fabric and colored paper. Just this absolutely rich assemblage of materials that make up this piece.

I could stay in front of this piece, I could talk about this piece, for the rest of the afternoon—but I could walk back and forth in front of this piece for literally hours, if I had the time and inclination. [Laughs]

LYNNE: The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism, currently on view at The Met, is an important milestone for the legacy of the Harlem Renaissance—and is the first New York City exhibition dedicated to the artists of the movement since 1987. But it’s also a significant moment for The Met.

You see, this isn’t the first time the Museum has mounted a show about Harlem. The first was called Harlem on My Mind, and it is one of the most controversial exhibitions of the twentieth century.

BRIDGET R. COOKS: The Harlem on My Mind exhibition had the subtitle Cultural Capital of Black America, 1900–1968, and it was mounted by The Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1969.

LYNNE: Here’s Bridget R. Cooks, professor of art history and African American studies at the University of California, Irvine.

Installation view, The Met’s Harlem on My Mind: The Cultural Capital of Black America, 1900–1968 (1969)

COOKS: It was incredible for a number of reasons. One is that it was the first time that The Met decided to create an exhibition focused on the representation of African American people. And second, it was also notable because the Museum decided not to include any artwork by African American people.

LYNNE: To put this into perspective: artists like Jacob Lawrence and Romare Bearden were alive and active at this time.

The exhibition took an almost sociological approach to Harlem. James Van Der Zee and Gordon Parks were included, but their photographs were incorporated as design elements throughout the exhibition—essentially, glorified wallpaper. Their inclusion didn’t feel intentional.

COOKS: It is a touchstone for how not to work with communities in terms of the way that mainstream museums should be thinking about holistic representation of the neighborhoods, the people, the history, the artistic stories and talents of and people that they are, at least on paper, committed to exhibiting in their galleries.

LYNNE: The presence of so many Black artists, so many fine artists, displayed in the exhibition The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism results in a project that feels really different than Harlem on My Mind. And one whose impact is different, too.

This exhibition celebrates the artists who worked in and beyond Harlem. It shines a light on these underrepresented and forgotten masters that will in turn inspire a new generation of artists and thinkers.

—

JORDAN CASTEEL: We’re all building upon the narratives of, quite literally, those who have come before us.

LYNNE: Here’s artist Jordan Casteel. Casteel is a celebrated painter in her own right working with a vivid palette creating large portraits and finding inspiration from many different subjects.

She was awarded a residency at the Studio Museum in Harlem. Like artists from the Harlem Renaissance, Casteel finds inspiration in the people and places that create her community. Her portraits of regular people who catch her eyes are celebrations of humanity.

CASTEEL: And I think that the Harlem Renaissance is a piece of that bigger puzzle. I think inspiration for many comes from a vast array of places. It comes from our grandmothers just as much as it comes from the names that we recognize, whether it be Langston Hughes or Charles White.

That those are names that for me, culturally, I understand as kind of milestones or bridges to my own success. That it was their struggle that has fed into my ability to make work today and to push against various structural systems or the expectations that are put on me and the ways that I’m supposed to make or not make, or the language around it. They have given me a playbook and a sense of confidence, and I think the Harlem Renaissance is a part of that.

LYNNE: Jordan considers herself and her work to be descended from the lineage of the great artists working around Harlem in the 1920s and ’30s.

CASTEEL: Many of the makers and creatives at that time would say that were similarly a part of a legacy of very talented creators and makers that were just ignored. So, they were perhaps the first to be recognized, but they were not at all the first to be of a group of talented people who were Black or people of color.

LYNNE: The ways that artists related to each other, supported each other, created art in conversation with each other hasn’t changed much.

CASTEEL: I think there’s a lot of truth in the Black art community now that it’s pretty small still, and we all know and support one another. And that feels important just inherently, perhaps because there have been people before us who have done the same and recognize the importance of that and knows that the change can happen when we step forward en masse and say we want something different.

LYNNE: Jordan makes a point about the struggle for social justice as it relates to being an artist. Identity is important for solidarity but working from that place can also become a constraint.

CASTEEL: Being Black, young, a woman—all of those things would stand before my art. People would see me as those things first, and then as a result, my work would always be inherently political. Whether I was painting a red square or a pink square or painting a Black body, that all of those things, like other people’s anxieties about my body and space, or other people’s questions about how my body and space exist, would be kind of placed on the work itself.

So, when I think about the power or the importance of art and social justice, I think that there are ways in which we can adapt to the narratives or the expectations of others, but also recognize the history that has written us out.

For me, painting people of color is important because there is just so much room for more representation of people of color in high art. Whether I am painting a landscape or I am painting people in my community is going to inherently hold a sense of responsibility to social justice, whether I want it to or not.

LYNNE: It’s not hard to imagine that the artists of the Harlem Renaissance might’ve had similar feelings. To quote a son of Harlem, writer and activist James Baldwin, “I am not an exotic rarity.”

The reality is that they were a part of a transatlantic collection of writers, painters, and musicians moving away from traditional ideals. Wading into uncertain waters in search of beauty and truth.

Like those before them and those after, carrying on a mysterious vocation that’s as elusive as it is human. What do I have to say? What do I think is beautiful? This is how I see the world.

—

CAMPBELL: Augusta Savage, honestly, was one of my heroes of the Harlem Renaissance.

LYNNE: Here’s Mary Schmidt Campbell again.

CAMPBELL: She was recognized as a gifted artist from a very young age.

LYNNE: Growing up in Florida, Augusta developed a love for sculpting. She shaped figures out of the South’s red clay and eventually, in 1921, her talents led her to New York.

CAMPBELL: She comes to New York, goes through Cooper Union in three years. It's a four year program, she gets through in three years.

She immediately begins sculpting these magnificent busts of W. E. B. Du Bois and Marcus Garvey and wins the capacity to study in Paris.

LYNNE: Augusta Savage moved to Paris and studied for several years before returning home.

CAMPBELL: She comes back to Harlem in about 1932 and she takes an absolute leadership role.

LYNNE: Savage created an extraordinary body of work while also making time to mentor younger artists.

CAMPBELL: She had something called the art garage that she opened up. And artists like Norman Lewis or Romare Bearden would come by and she would first give them a broom and have them clean up, but she also helped them understand what it meant to be an artist. And Romie said that just watching the extent to which she worked and how hard she worked and how dedicated and focused she was, he said, was instruction in and of itself.

LYNNE: She was a leader of the Harlem Artist Guild, owned a gallery, and was the first director of the Harlem Community Art Center.

In 1939 she was commissioned to create a sculpture for the New York World’s Fair. It was a monumental work, sixteen feet tall at its highest point, designed as a series of figures arranged to look like a harp. Augusta Savage wanted to create a sculpture that honored the musical contributions of Black people.

It was a hit. Postcards were printed with its image and replicas were sold as souvenirs.

Augusta Savage (American, 1892– 1962), Lift Every Voice and Sing (The Harp), 1939. Bonded bronze, 10 1/2 x 3 x 7 in. (26.7 x 7.6 x 17.8 cm). University of North Florida, Jacksonville; Thomas G. Carpenter Library, Special Collections and Archives, Earthe M.M. White Collection

MURRELL: Lift Every Voice and Sing, which was inspired by a song by James Weldon Johnson, that later acquired the subtitle, I think even officially, but certainly informally as the Black national anthem. And that it was a song that was sung during a lot of the fifties and sixties civil rights movements.

And so what she’s doing here is visualizing certain lines from that song depicting… I think there are twelve individual figures. Their faces are differentiated but not individualized. They are emblems, they’re symbols of the individuals that collectively make up a community. And they’re standing on this base that reflects the song’s reference to the hand of God.

CAMPBELL: She had to make the piece in plaster because she could not afford to cast it in bronze or use any more durable material. It was very popular.

But the real heartbreak is that at the end of the fair, she couldn’t transport it, she couldn’t move it. She had no place to store it, and so it actually had to be destroyed.

LYNNE: This loss is a reminder of the importance of conserving, honoring, and celebrating the work of the Harlem Renaissance.

Denise Murrell has thought about reconstructing Lift Every Voice and Sing.

MURRELL: I’ve had discussions with various art historians about the idea of reconstructing it.

If you think about works that are in The Met right now—Greek and Roman—many of those sculptures are created from fragments. Huge chunks of what we see today is and often an imagined reconstruction. We don’t have photographs or paintings that show us what that actual figure looked like.

Or in the nineteenth-century galleries, Rodin or Degas, all of the sculptures of Degas were cast in bronze after his lifetime from plaster or wax or other models. So is there an art-historical rationale for reconstructing this work in its full monumentality?

LYNNE: Hopefully one day this idea can be fulfilled. Augusta Savage’s masterpiece Lift Every Voice and Sing reconstructed, standing tall, a tribute to a time when Harlem gave the world art and song and celebrated a people who had endured unimaginable horrors.

A time when communities across America and beyond lifted their voices and sang.

I wish I could sing well, because this song and its message are so important to me. I grew up singing it in church, at family functions, Juneteenth celebrations. We had competitions about who knew every word to all three verses best.

It’s a nice thought, one day standing in the shadow and brilliance of a reimagined Augusta Savage sculpture named after it.

I like to imagine it by this one overlook I love at Marcus Garvey Park, between 120th and 124th Streets. Or maybe in Saint Nicholas Park near City College, overlooking the part of Harlem where so many of the artists and writers I admire found a home.

At sixteen feet tall, it would be a reminder of Harlem’s beautiful history, a symbol of inspiration, and proof of that extraordinary moment in time now known as the Harlem Renaissance.

[“Lift Every Voice and Sing” by The Manhattan Harmony Four plays]

—

LYNNE: Thank you so much for listening to Harlem Is Everywhere. To close out our series, we wanted to share a poem by Major Jackson, written in response to Romare Bearden’s monumental collage, The Block.

Major Jackson is a professor at Vanderbilt University, where he is the Gertrude Conaway Vanderbilt Chair in the Humanities. Although he’s a professor of English and creative writing, he’s taught Bearden’s work in his literature classes because of its strong sense of narrative.

Romare Bearden (American, 1911–1988), The Block, 1971. Cut-and-pasted printed, colored, and metallic papers, photostats, graphite, ink marker, gouache, watercolor, and ink on Masonite, 48 in. x 18 ft. (121.9 x 548.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Samuel Shore, 1978 (1978.61.1–.6)

MAJOR JACKSON: I’m Major Jackson reading “The Block (for Romie).”

A village though, holy presence

in the bricks, to see through walls

with our eyes. Bodies assembled such that traffic

stays on the margins but the bright river,

though stilled on one Harlem avenue, flows out

from thresholds and doorways

where penny-colored faces profile like noble silhouettes,

and thus, this tension between life’s rush

and final doom. Someone has died,

and a hearse awaits, Bearden seems to say,

for us all, swimming with his mouth wide open.

No smirks from those held by the panorama.

To cross a corner, to sit sullen

on a staircase, to grasp a child from behind

weaves a cherished landscape of propositions.

A mother is half a Madonna,

and a blue bulb’s filament looms above the saints

of Sunrise Baptist where hymns are heard melodies,

where a prayer book, a candle, an altar

fix us to Southern roads. Why leave

when so much is here to observe?

The syncopated dailiness is Greek in proportions.

Even a barbershop acts as mirror,

all snips and shears and fades.

We, too, resurrect and ascend

and shake hands with Ethiopian angels,

and what carries the music

of our ascension is life, an improvised

resurrection, a colorful bricolage

of ritualistic seeing, tenements played

like keys, a communal blues, our imperative

for tenderness, lovemaking at dusk,

a billowing curtain serene as a kiss.

Here, there are no secrets.

These bodies in repose, bodies rising from twin

metal frame beds, bodies soaking in tubs,

bodies watching TVs as boats sail on,

children at play above hopscotch squares,

what are they but the affirmative dream

of a city whose arrivants are dignity personified?

Look closer, look in:

animals are here, too.

A yellow pigeon coos on an awning,

another pair on a rooftop,

seagulls lift and angle into thermals,

a dalmatian stands beside a boy

as if in a Brueghel.

The tenements on Lenox between 133rd and 132nd

proclaim the flaneur’s feast: a mother calls down

from a window to remind her daughter

of ingredients for potato pone, pork belly, and cow peas.

At the corner store, a couple leans

against glass oblivious of the nearby crowd

seeming to convene a second line.

We are not without our vices

so says the bright neon Liquors sign

and the blanketed man whose made concrete his bed.

Several floors above,

a window is a mouse trap.

But the old folk from the fields

hold sentry like F. Douglass in portraiture,

and H. Tubman, and may we

revere them, may they occupy the periphery

of our vibrant canvases.

We are entangled in geometric shapes.

Our limbs are their limbs.

In cities, feelings pass through walls

—

LYNNE: Many thanks to Major Jackson and Mary Schmidt Campbell, Bridget R. Cooks, Denise Murrell, Jordan Casteel, and to you for listening.

Harlem Is Everywhere is produced by The Metropolitan Museum of Art in collaboration with Audacy’s Pineapple Street Studios.

Our senior producer is Stephen Key.

Our producer is Maria Robins-Somerville.

Our editor is Josh Gwynn.

Mixing by our senior engineer, Marina Paiz.

Additional engineering by senior audio engineer, Pedro Alvira.

Our assistant engineers are Sharon Bardales and Jade Brooks.

I’m your host, Jessica Lynne.

Fact checking by Maggie Duffy.

Legal services by Kristel Tupja.

Original music by Austin Fisher and Epidemic Sound.

The Met’s production staff includes producer, Rachel Smith; managing producer, Christopher Alessandrini; and executive producer Sarah Wambold.

This show would not be possible without Denise Murrell, the Merryl H. & James S. Tisch Curator at Large and curator for the Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism exhibition; research associate is Tiarra Brown.

Special thanks to Inka Drögemüller, Douglas Hegley, Skyla Choi, Isabella Garces, David Raymond, Ashley Sabb, Tess Solot-Kehl, Gretchen Scott, and Frank Mondragon.

Asha Saluja and Je-Anne Berry are the Executive Producers at Pineapple Street.

Support for this podcast is provided by Bloomberg Philanthropies.

###