The collaboration between the entertainer Joyce Bryant and the designer Zelda Wynn Valdes is a tale of two women defying gravity. Each soared despite the weight of racism in the United States during the mid-twentieth century: Wynn Valdes became a successful entrepreneur and designer, while Bryant’s spectacular voice and beauty made her a barrier-breaking nightclub sensation. During a five-year period, their creative partnership resulted in one of the most promising entertainment careers of the early 1950s, fueled in no small part by some of the most inspired work of a gifted designer. Over time, however, the achievements of these pioneering figures have grown obscure.

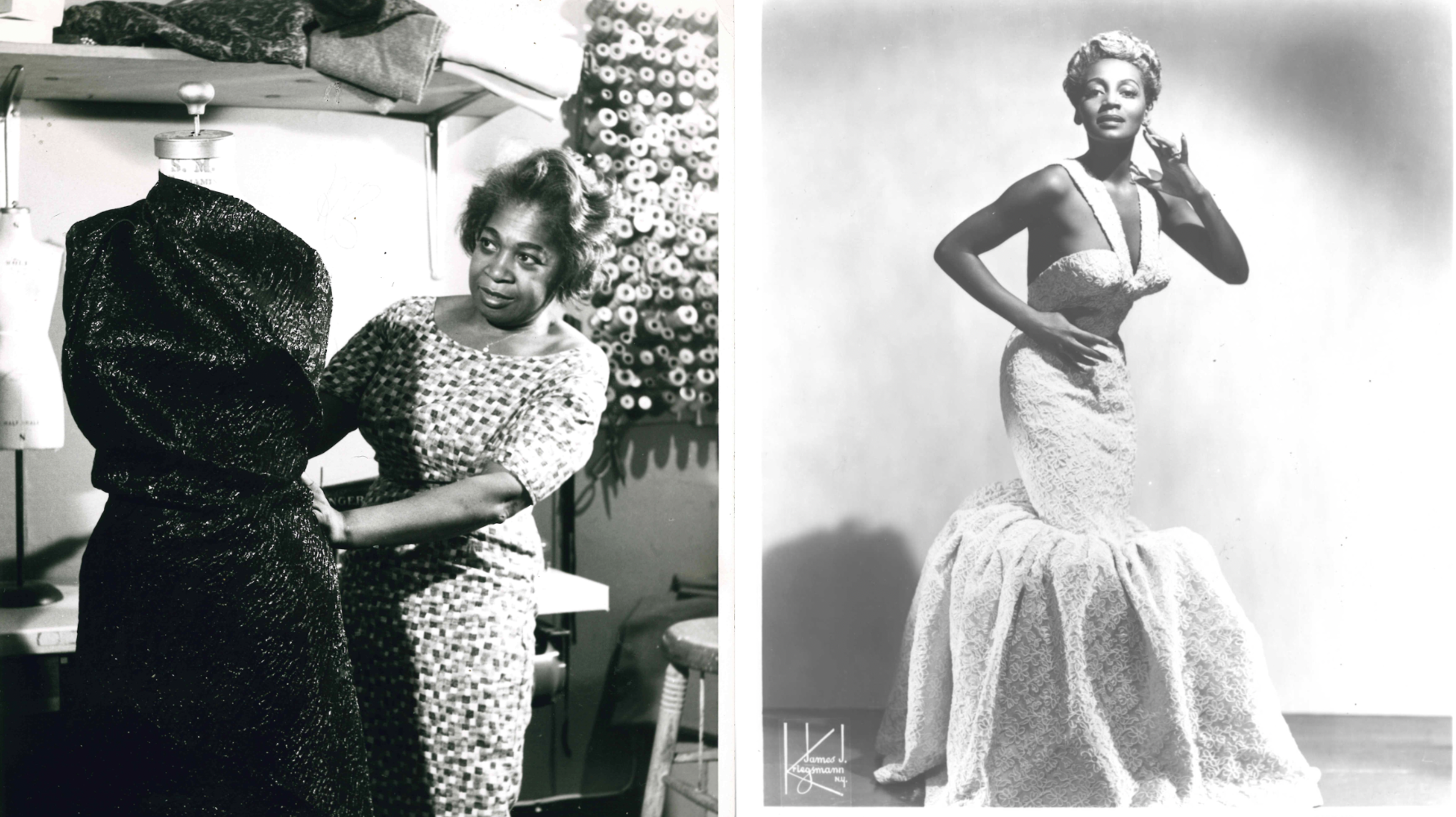

Left: Image of Zelda Wynn Valdes with one of her costumes at the Dance Theater of Harlem. Courtesy Dance Theatre of Harlem Archive. Right: Image of Joyce Bryant, 1953. Courtesy Jim Byers

Both women were initially unknown to me as a pop culture-obsessed teen in the early 1980s. I first encountered Bryant while flipping through bound volumes of LIFE magazine in my D.C. prep-school library. This fierce, dark-skinned beauty seemed to literally take a swing at me from the page in an article titled “Bryant The Belter: Punchy Singer Slugs Off Four Pounds Every Night.” In 1953, only a Black entertainer of considerable stature would have earned a five-page feature article in LIFE, with photography by Philippe Halsman. I soon found a plethora of features, reviews, and full-page ads in Billboard and Variety. Bryant was a prolific presence in the Black press of the early 1950s, often in conjunction with designer Zelda Wynn Valdes. Archival information on Bryant was abundant, but nobody was looking for it, which inspired me to learn more.

Image of Joyce Bryant at the Copacabana taken by Philippe Halsman for LIFE. Photo by Philippe Halsman © Philippe Halsman Estate 2024

In the years since my high-school-library days, I became an ardent collector of all things Joyce Bryant. Working as a freelance music critic for The Washington Post, I successfully pitched a feature article on her. We began to share hour-long phone conversations, which made it clear that Bryant’s story demanded more than just an article. After befriending this elusive star, I started extensive research as her authorized biographer and interviewed a broad range of contemporaries for a documentary. Those interview subjects included designer Zelda Wynn Valdes.

Wynn Valdes is remembered today for her impactful legacy in costume design. In 1969, Arthur Mitchell hired her for what became a three-decade stint as the principal costumer for the Dance Theater of Harlem (DTH). Earlier in the decade, publisher Hugh Hefner had engaged Zelda to produce a group of Playboy Bunny outfits. She became the first to stage a fashion show at the New York club in 1963, followed by a series of presentations within this desegregated social space that became known as “Zelda at the Playboy.” Wynn Valdes was known to both for her now largely overlooked success as a designer of dazzling gowns for celebrities ranging from Dorothy Dandridge, Mae West, and Ella Fitzgerald to Eartha Kitt, Marlene Dietrich, and Josephine Baker. The gowns were exquisitely crafted: “I made the designs for the beading, and I had an Italian lady who did the beading for me. She lived in the Bronx,” recalled Wynn Valdes, speaking of the old-world skills lavished on her gowns. “At one point, I kept nine dressmakers busy.”

Eartha Kitt dressed by Zelda Wynn Valdes (detail), 1952. Photo: Gordon Parks (American, 1912–2006). Courtesy Gordon Parks/The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

“[Ella] called me from Russia,” Wynn Valdes reminisced in 1999 when I interviewed her in the DTH costume studios days before her retirement. “‘Hello, you don’t know me, but I’m Ella Fitzgerald. I’ve heard so much about you… I’m opening at the Mocambo in Hollywood in five days, and I need four gowns. Can you make them and send them to [Los Angeles] by plane?’” The long-distance designs were for Fitzgerald’s fabled appearance at the chic Hollywood nightery, highly unusual for a jazz singer in early 1955. Glamorous African American song stylists such as Dorothy Dandridge, Eartha Kitt, and Bryant had previously headlined to acclaim at the Mocambo.

Despite her vocal prowess, the full-figured Fitzgerald did not fit the accepted notion of the slender, eye-catching beauty that was associated with the club. The personal guarantee that the superstar Marilyn Monroe would attend every performance of her favorite vocalist helped Fitzgerald get the prestigious booking. Zelda’s gowns were integral with assisting the audience to envision a new, more sophisticated Fitzgerald. Months afterward, the singer recorded the first of the iconic “Songbook” albums for which she is still most revered. In the widely known images of Ella ringside with Marilyn at the Mocambo, she is gowned by Wynn Valdes, as she would be for years to come.

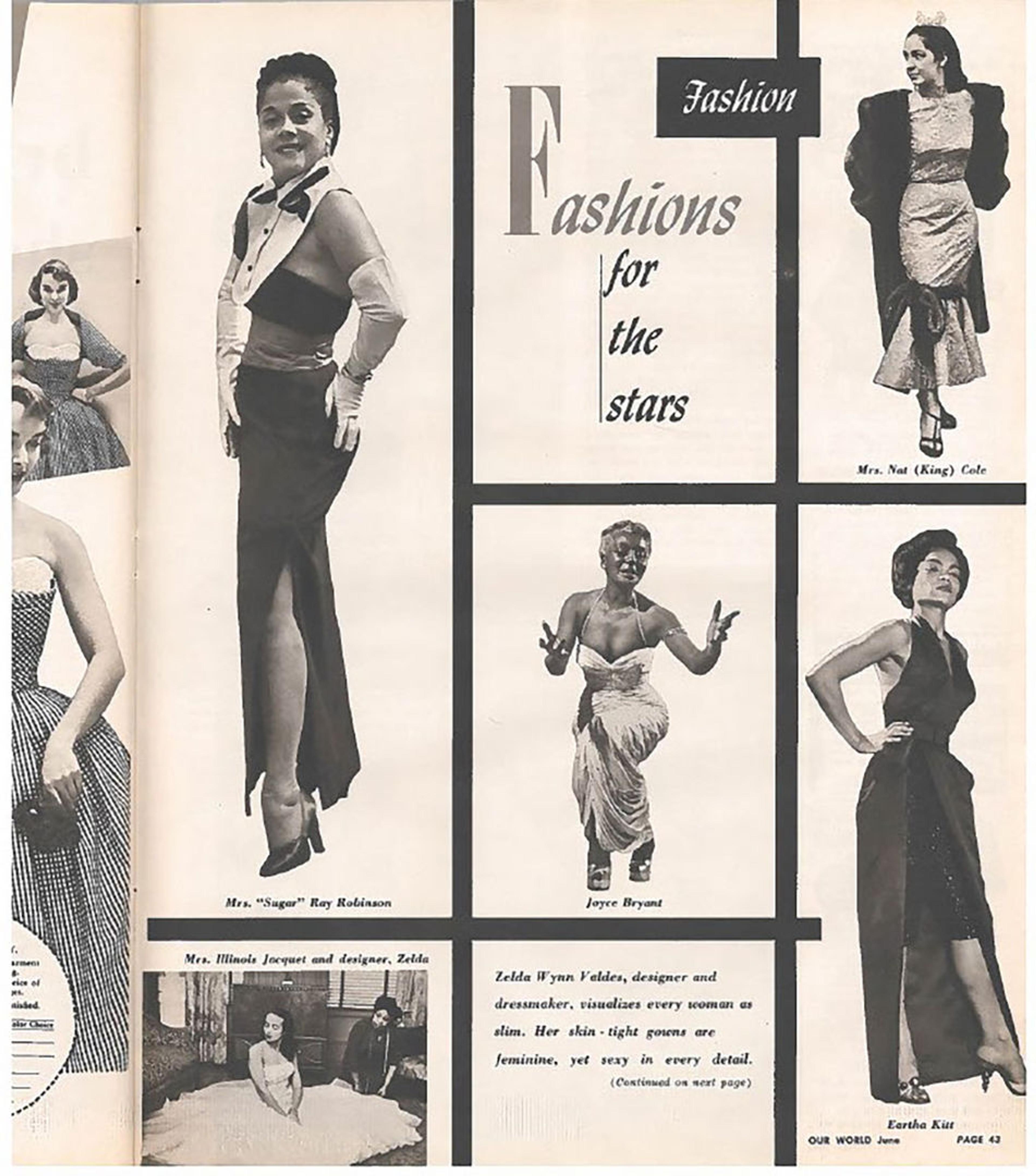

Page from Our World magazine, 1953. Courtesy James Byers

Born Zelda Christian Barbour in 1905 in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, Wynn Valdes learned to sew from her mother and grandmother. After apprenticing in her uncle’s tailor shop in White Plains, New York, Wynn Valdes became the sole Black clerk and later a tailor at a nearby upscale boutique. In White Plains, Wynn Valdes opened her first shop in 1935, cultivating both Black and white clients. Among her devotees were socialite Edna Mae Robinson (wife of boxing champion “Sugar Ray” Robinson) and singer Maria Ellington, for whom she dressed the entire wedding party of her 1948 marriage to superstar musician Nat King Cole. That same year saw the opening of Zelda Wynn, considered the first Black-owned business on Broadway. The following year, she was among the founding members of the National Association of Fashion and Accessory Designers, an organization that sought to advance the participation of African Americans in the industry, spearheaded by the National Council of Negro Women.

But it was Wynn Valdes’s five-year collaboration with Joyce Bryant between 1951 and 1955 that was perhaps the most transformative for both women. “Eartha was a dancer, so she had very definite restrictions about how she needed to move and everything,” recalled Wynn Valdes. “But Joyce told me ‘I don’t know what I want or need.’ So, I told her to just leave it up to me!” The resulting collaboration helped transform Bryant’s young nightclub career into one of the most promising of the early 1950s, partly because she allowed the talented designer free rein for her most adventurous and beguiling creations.

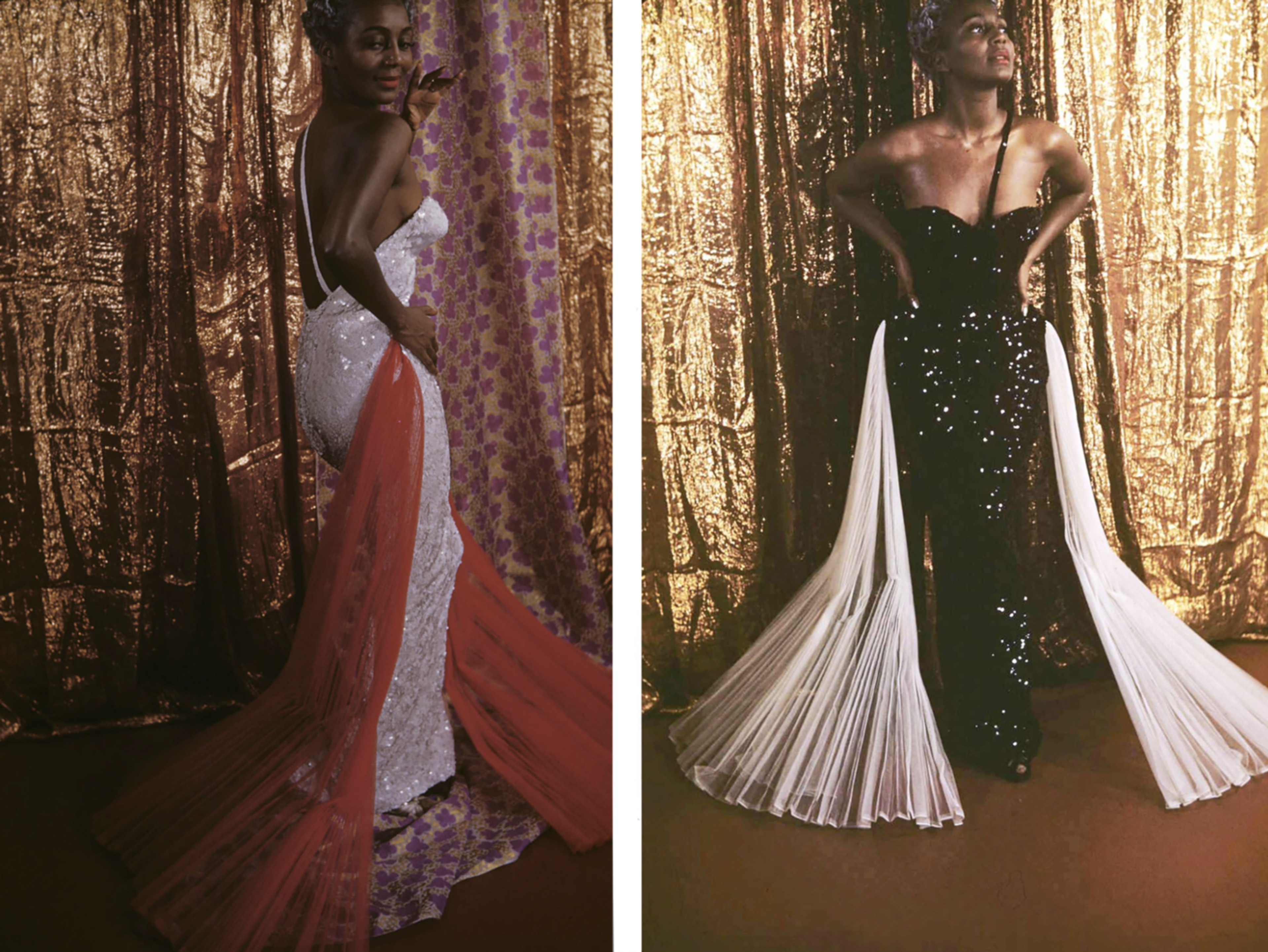

Left and Right: Two images of Joyce Bryant, late 1940s and 1953. Courtesy James Byers

In the spring of 1951, Bryant made her first major East Coast appearance at Bill Miller’s Riviera, a cliffside showplace on the Palisades of Fort Lee, New Jersey, which enjoyed a brief post-WWII run as a top venue on the New York club scene. The star-making entertainment reporter Walter Winchell proclaimed Bryant “The Voice You’ll Always Remember.” In tune with the buzz, Wynn Valdes caught the show, and to her surprise, Bryant’s demure, off-the-rack look was in striking contrast to her vibrant and alluring voice. Bryant recalled that the designer returned to the Riviera the following day. “‘I want to work with you,’ Zelda said… and presented me with a gown as a gift. It wasn’t my size, but it was fabulous, and it was more about the gesture than anything else. I wore Zelda’s gowns exclusively from then on.”

Skin Tight

Bryant’s lean but curvaceous body became a canvas on which Wynn Valdes painted her most adventurous creations. “[Zelda’s gowns] were very tight. I mean, they really left nothing to the imagination,” Bryant recalled when I interviewed her in 2001. My co-producer and videographer Rob Farr and I were filming our in-progress documentary Joyce Bryant: The Lost Diva. “If I had a pimple… you’d see it.”

Born into a devout Seventh-Day Adventist family, Bryant (1927–2022) seemed an unlikely candidate to emerge as the first dark-complected Black woman promoted by the national media as a “love goddess.” Discovered during an impromptu nightclub sing-along on LA’s Central Avenue, the Oakland-born eighteen-year-old with a stunning four-and-a-half-octave range was hired on the spot to perform with the locally popular Lorenzo Flennoy Trio. Within months, she would make her first film appearance in Mr. Ace (1946). After going solo in 1949, Bryant created a minor sensation when her 1950 recording of “Drunk With Love”was banned from radio airplay for its allusion to unbridled ardor. But ultimately, her Riviera engagement and the resulting collaboration with Wynn Valdes put the singer on the road to national stardom.

Image of Joyce Bryant taken by Philippe Halsman, 1954. Photo by Philippe Halsman © Philippe Halsman Estate 2024

During her smash-hit debut at Manhattan’s prestigious Copacabana nightclub in the summer of 1953, Bryant was provocatively photographed by Philippe Halsman for a five-page feature in LIFE magazine. “At her hips, the Belter is so tightly packed in coral pink silk that she can barely bend, cannot sit down at all,” marveled one caption. “At her knees, the Belter’s dress is so tight that she can hardly perambulate, must walk with shuffling six-inch steps, and must be carried up and down stairs. But she has plenty of freedom above the waist to flail around violently.”

Ironically, these restrictions changed not only how Bryant moved but also gave her performances even more focus and intensity. She began using the growl of her lower register, bringing her gospel choir experience into the mix. Accompanying Bryant’s assertive new look was a new confident edge to her sound, best exemplified by her renditions of “You Made Me Love You” and “Love For Sale,” and critics noticed. “A sizzling sepia personality blasted into the Mocambo Tuesday night, and in Joyce Bryant, the Charlie Morrison spot has a sure-fire hit that should jar the town,” noted the Hollywood Reporter in 1953.

Bryant herself contributed to recasting her own image in 1952 when booked to open for the legendary Josephine Baker in Los Angeles. “[Josephine] could fascinate the audience by just walking on stage,” Bryant remembered. “I knew I had to do something.” In an age before cosmetics manufacturers had bothered to develop products that could tint Black hair easily and safely, Bryant made a bold choice. “I coated my hair with lanolin oil and then painted my hair with metallic silver radiator paint. So, when the curtain rose at the Shrine Auditorium that opening night… the crowd just went berserk! Zelda had made a special silver beaded gown. My inch-long nails were painted silver. I wore a floor-length silver mink and diamond jewelry. I stopped everything.”

Advertisement of Joyce Bryant for the Thunderbird in Las Vegas Nevada, 1953. Courtesy James Byers

It is also notable that makeup manufacturers did not yet produce makeup for dark-complected women. With no cosmetics available in her shade, Bryant then wore only lipstick and lashes but oiled her flawless skin with sweet almond oil. Under the lights, she was a vision in shimmering mahogany with chrome hair. Bryant exited to thunderous applause from an agape audience of Hollywood royalty. “Josephine and I passed one another in the wings, and she smiled and said to me, ‘Touché!’”

Defying Gravity

Wynn Valdes’s gowns for Bryant were some of the first that were both strapless and backless. While strapless gowns often sit high on the back, Bryant’s gowns plunged dramatically toward the small of her back. Using intricate cantilevered boning and elastic within the bodice, Joyce described the front of the gown as actually pressing back against the wearer’s rib cage, standing up independently and allowing for the dramatic backless styling. But early on, there were occasional wardrobe malfunctions.

Two photos of Joyce Bryant by Carl Van Vechten, 1953. Courtesy Yale University photos

“It happened to me at the Copa… I knew I was out of the gown because I could feel the air!” Bryant recalled during one of our initial telephone interviews in 1998. “They called me The Belter—I was a very vigorous singer… just arms everywhere. [Zelda] devised a way that the gown was sort of loose around the bosom. So, if I did come out, I would go right back into the gown. But it was just so quick… and I didn’t let it mess with my mind.”

Bryant’s voice and newfound glamor broke down barriers for Black entertainers. With her December 1952 appearance in the Aladdin Room at the new Hotel Algiers, Bryant became the first Black entertainer to perform in a Miami Beach hotel. While Black performers, including Bryant, had appeared in standalone Miami nightclubs such as the Clover Club, Latin Quarter, and the 5 O’Clock Club, it was unheard of for a Black artist to obtain a prime booking in a hotel show room. African Americans were required to be off the streets of Miami Beach before sundown. Unless they could present an ID proving they were wait staff at one of the hotels, they risked arrest or worse.

Bryant’s triumphant performance was lauded in the national media for opening the door for Black entertainers on the important Miami Beach nightclub circuit. In many ways, glamor was a velvet hammer that broke significant barriers for entertainers in the early stages of the Civil Rights Movement. “Joyce Bryant got into spaces like the Coconut Grove a decade before me,” famed jazz singer Nancy Wilson told me during our interview about the pioneering entertainer: “Without Joyce, there would have been no me.”

In many ways, glamor was a velvet hammer that broke significant barriers for entertainers in the early stages of the Civil Rights Movement.

Perhaps the most iconic of Wynn Valdes’s gowns for Bryant is the one worn for Jet magazine in their October 1, 1953, cover feature “The Sexiest Gowns in Show Business.” Here, Bryant looks askance, wearing a skin-tight, intricately beaded gown that seems to have a life of its own.. Two wide shoulder straps narrow as they plunge downward, both covering and accentuating her decolletage. Ironically, while the 1953 photo was among her most widely published, Bryant only briefly utilized the gown in performance. “That dress was one of the few Zelda designed for me that was uncomfortable,” Bryant shared. “It must have weighed forty pounds. And under the lights, the material on my shoulders made me so hot. I just couldn’t wear it onstage.”

While Wynn Valdes’s career continued for decades, Bryant’s took different directions. Just months after this television appearance, in November 1955, Bryant walked away from what had been among the most promising nightclub careers of the first half of the fifties. “I felt like a piece of meat. A piece of something… nothing. I just knew I had to get away.” Before touring for several years as a musical missionary for the Adventist church, performing concerts of religious and gospel music, Bryant returned many of the gowns to Wynn Valdes. Jet magazine noted that socialites and entertainers hoped to snag one of “Belter Bryant’s” used gowns at Zelda’s Broadway store. After training with famed Howard University voice coach Frederick “Wilkie” Wilkerson (1913–1980), Bryant resurfaced in the early 1960s touring for several years as the lead in the New York City Opera’s touring company of Porgy and Bess. In the mid-1970s, she would return to the Manhattan nightclub scene, headlining at the Rainbow Room, Cleo’s, and Harlem’s New Cotton Club. She would coach a range of performers from Loretta Divine and Raquel Welch to Michelle Rosewoman and Phyllis Hyman before retiring to Los Angeles, where she passed away in 2022 at the age of ninety-five.

Two of Joyce Bryant’s last publicity pictures from 1955. Courtesy James Byers

Sadly, only a handful of Wynn Valdes’s creations from this period survive, including one designed for Eartha Kitt in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. However, the creative energy embodied by the collaboration of these two pioneering women continues to have an indelible impact. Apollo Theater patrons still marvel at Bryant’s image in the mural in the lobby, and the costumes worn by the Dance Theater of Harlem thrilled generations of dance lovers around the world. Both were in no small part inspired by the work of a designer allowed to unleash her most ingenious ideas on gowns for one of the great entertainers of the twentieth century.