أيتها الارض الزعترية

ما لون الزعتر فيك الآن

وما لون الارض

وهل يطلع الزعتر من بقع الدم

أم نزف الدم من الزعتر ؟؟

Oh, the land of zaatar [1]

What color is your zaatar now

And, what color is the land [2]

Does zaatar blossom from blood

Or, does zaatar itself bleed ??

Akram Al Najar, The Palestinian Journey, in Life and Death (1983)

Palestine carries in its soil and rivers the collective memory of an Indigenous, multicultural, and religiously pluralistic people who have cultivated and cared for the land for centuries.[3] During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Palestine consisted of Muslim, Jewish, Christian, Druze, Baha’i, Sikh, Hindu, and Zoroastrian populations living alongside other ethnic minorities, such as Armenians.[4] The majority of the people lived in more than eight hundred villages as fellahin (“people of the land”) who depended mainly on agriculture for their livelihood.[5] Each village maintained a localized collective identity, constituted through its special arrangement of homes, orchards, places of worship, marketplaces, open meeting places, and burial grounds. Palestinians considered their village to be “a family of families,” closely linked in common history, shared memories, and heritage practices.

Through the cultural practice of embroidery known as tatreez, Palestinian women and girls decorated their thobe (or dress) with symbols of history, memory, and place, telling the tale of the maker’s life and her connection to the land through an illustrative medium of colorfully stitched motifs. Until the mid-twentieth century, Palestinian dress styles reflected an “individual or a place: a wife, a mother, a daughter, a family, a house, a village, a town, a field, a market.”[6] The thobe marks the owner’s life and explicitly holds a woman’s biographical details through the needlework techniques used, the threads chosen, and the harmonious balance of colors, as well as each maker’s interpretation of traditional patterns that tell her story in stitches.

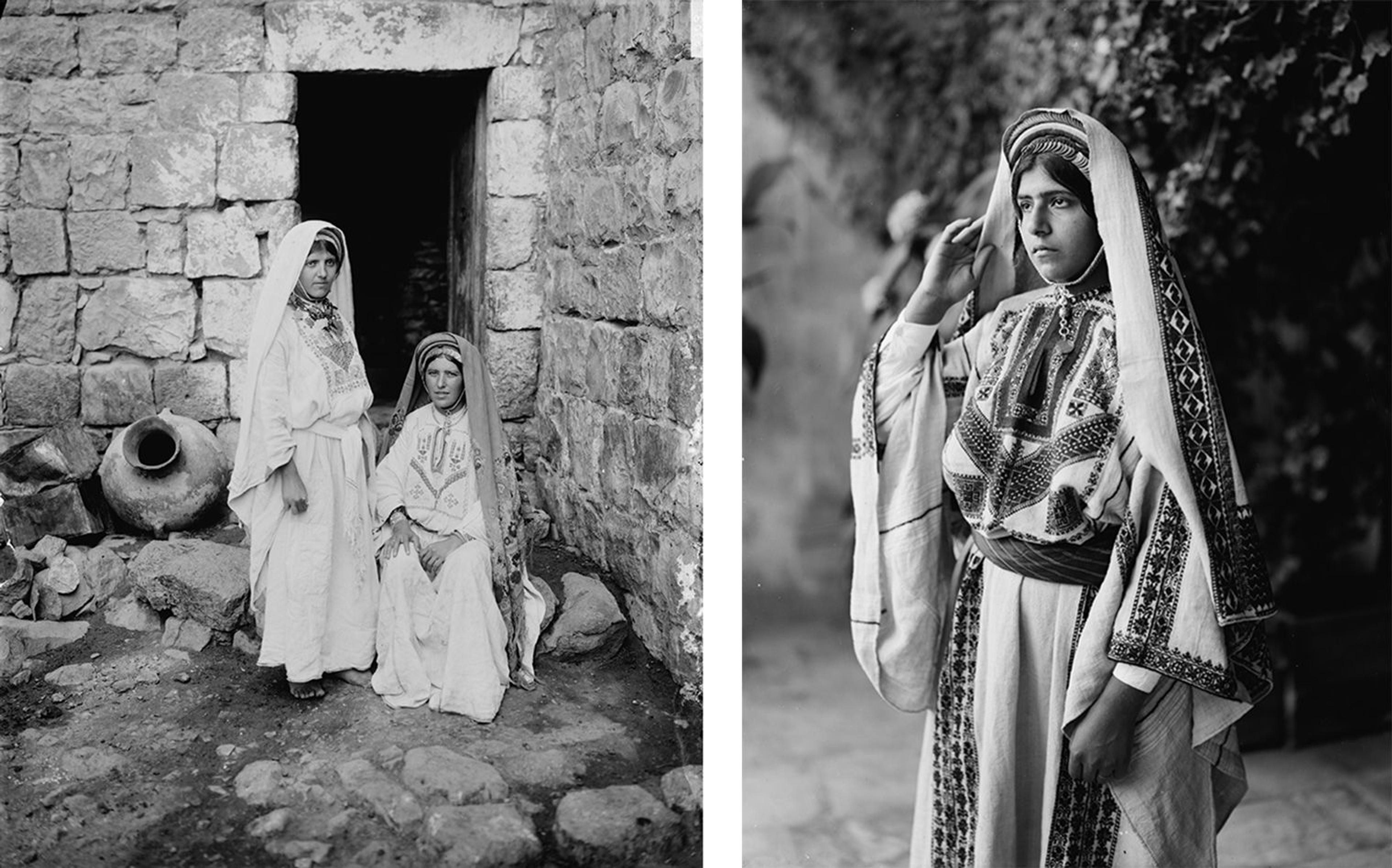

Mother and child from al-Khalil, 1930s. Khalil Raad (Lebanese, 1854–1957). © Institute for Palestine Studies, Beirut, Lebanon

While the fashion of the thobe is bound by time period—defined by regional traditions, sociopolitical influences, and material availability in each respective era—the thobe also embodies timelessness in its centuries-old visual language, telling the tale of the maker’s life years later and far from home. The governing style of each thobe signified a woman’s village, tribe, or town; her marital status; and whether her life was materially impacted by missionaries, colonialism, or war. More broadly, the thobe documents the history of Palestinian women and girls, operating as a visual language that has been passed down between generations through oral transmission. Palestinians have preserved that history, along with the memories of their villages and their collective identity, for their descendants in the diaspora. When elders have lost tatreez traditions through war and displacement, the next generation threads their needle with only the muscle memory of their hands to guide them.

The ancient farming communities of Palestine bore witness to great empires and their armies that came and went over the centuries, but they were not a transient population. The fellahin belonged to a civilization that enriched the heritage of humankind, producing scholars and mystics who contributed to the study of religion, literature, philosophy, architecture, and the sciences.[7] With the passage of time, Palestinians saved the surviving remnants of their recent past, such as harvest baskets, woven fabrics, glass ewers, painted ceramics, and embroidered dresses, resisting cultural erasure and memorializing the lives and legacies of makers now lost. As a result, oral histories and Palestinian photographic archives are now the richest source of knowledge about the art of embroidery and tatreez as a form of intangible cultural heritage.[8]

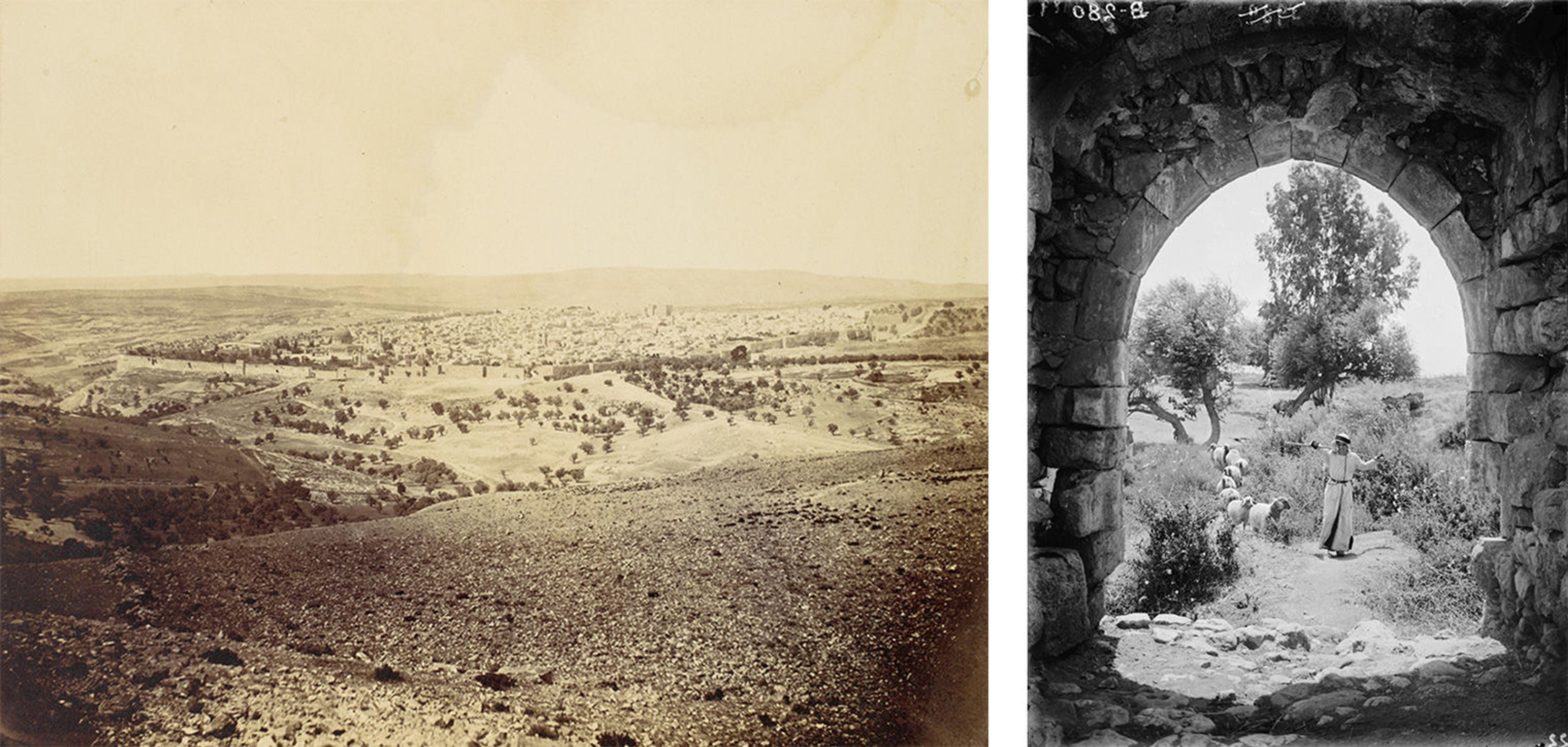

Yet in various historical and contemporary accounts, Palestinians are often rendered nameless and placeless. The Palestinian scholar Edward Said once observed in his book, After the Last Sky: Palestinian Lives (1986), “Exile is a series of portraits without names, without contexts. Images that are largely unexplained, nameless, mute.” Very few, if any, photographs of Palestinians taken during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries provide clues about who these individuals were and where they came from. Whether through the travel photography of John Anthony and Maxime Du Camp that is absent of human life, or the photographic collections of unnamed people posed as biblical characters archived at the Library of Congress—Palestine was represented in the American and European photographic lens as an ancient place of the distant past, belonging more to the world of the Bible than to a living, thriving, socially inhabited place with Indigenous people.[9]

Left: “[Jerusalem],” showing a thriving and socially inhabited city as deserted and without any sign of human life. [Jerusalem], 1860s. John Anthony (British [born France], 1823–1901). Albumen silver print from glass negative, 6 1/2 x 8 5/8 in. (16.3 x 21.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of A. Hyatt Mayor, 1961 (61.641.2.1). Right: An unnamed Palestinian man poses as a Biblical subject for an American photographer during the early twentieth century. Set of thirteen select slides of shepherd life, illustrating the Twenty Third Psalm. ‘He leadeth me in paths of righteousness,’ ca. 1900–1920. American Colony (Jerusalem). 1 negative: glass, dry plate; 5 x 7 in. (12.7 x 17.8 cm). Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection (LC-DIG-matpc-05673)

After the installment of the train line between Yaffa and Jerusalem in 1892, tourism surged. Major American magazines and newspapers, such as the fashion magazine Vogue, advertised “Holy Land” travel packages and deals throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.[10] Nineteenth-century Orientalism and the popularity of “Holy Land” travel made way for the selling, looting, and reselling of cultural objects as souvenirs. Travel guides urged tourists not to engage with local cultures and to ignore the real identities of the Indigenous people in favor of biblical caricature, a type of Orientalism called “Biblification.”[11] When traditional Palestinian dresses were brought back by tourists to North America and Europe, museums, informed by the same Orientalist beliefs, took a keen interest in collecting and exhibiting them erroneously as biblical styles.

The Met’s Palestinian dress collection, for instance, includes twenty-seven Palestinian women’s ensembles, totaling thirty-seven dresses, coats, scarves, jackets, headdresses, and other garments—more than half of which were donated to the Museum prior to 1948. Interestingly, the collection is composed entirely of dress styles that originate from villages and towns along the “Holy Land” pilgrimage: Yaffa, Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Ramallah, and Jericho. The“Holy Land” phenomenon is vital to understanding the social and cultural forces that motivated collectors to acquire and bring these dresses to America. Despite the objects being so intimately linked to the hands and bodies of the people who made and wore them, there remains a deficit of information about the maker in the object records of museums and collections almost everywhere.[12] The Met’s collection of dresses must be contextualized within this phenomenon to understand whether the garments were made by Palestinian women for personal wear, produced by Palestinian women for tourists, or made by Americans recreating biblical styles for New York theatrical productions.

While the absence of archival records disconnects the maker from her dress, the thobe itself reflects tangible and intangible aspects of identity. Palestinian tatreez patterns, thread colors, and adornments often express the maker’s relationship with her village and society, and the materials and techniques she used attest to her regional identity, individual personality, interests, and at times her sense of humor. During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, tatreez patterns on the thobe depicted specific flowers, trees, plants, and animals that were part of the natural landscape in Palestine. These patterns are numerous, and a single motif such as the tree of life, or saru, could have seemingly endless variations from maker to maker.

Study of these dresses, however, exceeds technicality and craftsmanship, moving beyond simply understanding their materials and construction. The materiality of a well-worn dress is an intimate look into the wearer’s life: fabric discoloration where her belt once girdled her waist, a protruded and stretched skirt precisely where her knees once folded, or tatters at the hem she once, perhaps, distraughtly stumbled upon during a daily errand. The function and performance of the thobe based on its wear and tear reconstructs the relationship between the wearer, the life she lived, and the way she interacted with her surroundings.

Left: A dress found on one of the Maronite mummies of Assi el Hadath cave in the Qadisha Valley, Tomb of Tyre, Lebanon, dated approximately 1283 CE. In Fadi Baroudi (ed.), Momies du Liban: Rapport préliminaire sur la découverte archéologique de ' Asi-l-Hadat (XIIIe siècle), Paris: Edifra, p. 67. Right: Ramallah everyday dress, mid-nineteenth century, most likely made by a 10-12 year old girl and her mother, for her first thobe. The embroidery in the skirt is stitched by more experienced hands than the chest panel. Robe, 1800–1942. Palestine. Linen, silk; embroidered, 51 1/2 x 53 1/2 in. (130.8 x 135.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of the Estate of Mr and Mrs. F. J. Shepard, 1942 (C.I.42.176.1). Photo by author

Each thobe serves as a rich study into the symbolic register for storytelling inherited by Palestinian women, generation after generation. The common, everyday thobe of Ramallah, embroidered in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries with red cross-stitch on an undyed locally woven linen, represents one of the oldest and most distinctive styles in the region. Similar work has been found on the dresses of eight female mummies in Qadisha Valley, Lebanon, dated to 1283 CE. The remarkable discovery of nearly complete medieval embroidered garments is of particular importance in the study of dressmaking traditions in the eastern Mediterranean, providing datable evidence of patterns, communal practices, and techniques that are still actively employed in the region today. The dresses were embroidered using red, blue, and brown silk threads, with motifs incorporating both curvilinear and rectilinear shapes that bear a striking resemblance to the motifs on Palestinian dresses during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Now, the tatreez patterns are known in the Palestinian tradition as the tree of life, zigzags, rosettes, and amulets that are believed to protect the wearer from evil, envy, and sickness.[13] It is possible that the motifs on the medieval dresses from Qadisha Valley had similar apotropaic functions.

During the mid-nineteenth century in Ramallah, the overcoat dress, or jellaya, with profuse cross-stitched patterns on an indigo ground cloth, was worn as a part of the formal bridal ensemble, while the white thobe with less embroidery was worn as daily attire.[14] After the inauguration of the Friends Girls’ School in 1869 by American Quakers, embroidery that was once taught at home moved to a school setting. As students were exposed to American embroidery and European fashion, tatreez patterns, fabrics, and thread colors used in the white thobe began to emulate European styles. Following the popularization of the white lace dress worn by Queen Victoria at her 1840 wedding to Prince Albert, white became the preferred color for the Palestinian Ramallah bride, who wore a heavily embroidered white thobe on her wedding day. By the late nineteenth century in Ramallah, the dark indigo–style garment was embroidered less intricately as it transitioned to daily wear.[15]

Left: Ramallah women wearing an everyday style of the white thobe during the late nineteenth century. 1 negative: glass, dry plate; 10 x 12 in. (25.4 x 30.5 cm). Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection (LC-DIG-matpc-11838). Right: A young woman from Ramallah, wearing the white thobe as a wedding dress during the early twentieth century. 1 negative: glass, dry plate; 10 x 12 in. (25.4 x 30.5 cm). Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection (LC-DIG-matpc-06842)

Along with changes in fabric colors, as well as density of worked areas, embroidery patterns and thread colors on the Ramallah thobe also underwent a transformation. In the mid-nineteenth century, motifs had been primarily geometric and abstracted, evoking the agriculture, flora, and fauna of Ramallah, such as poppy flowers, doves, palm trees, and grape leaves. By 1900, however, the dresses incorporated tatreez patterns that were realistic and curvilinear, depicting swans, peacocks, winged lions, and exotic florals not local to Palestine. Cross-stitch during the mid- to late nineteenth century had used natural dyes for silk threads, achieving shades of reddish rust, yellow, and green. In the later nineteenth century, silks dyed with synthetic colors, such as purple and pink, were increasingly used as well. But by the early twentieth century, Ramallah women embroidered almost exclusively with a deep burgundy color, and from the middle of the century onward, used only bright red and black cotton threads. The shift in thread colors perhaps speaks to the changing fashions throughout this period, as well as the difference in color shades achieved with natural dyes and synthetic dyes that arrived in Palestine as early as the 1860s.

Ramallah everyday dress, mid-nineteenth century, that measures approximately 128 centimeters long. The measurements of the thobe indicate that it was made for a 10–12 year old girl. While beads are unusual to find in the chest panel of Palestinian dresses, this dress incorporates 11 glass beads, 1 amber bead and 2 red coral beads. The sloppiness of the stitches and the inclusion of beads shows the inexperience of the young girl, and her playful personality. There are an additional 3 blue beads in the skirt embroidered by more experienced hands, perhaps by her mother, to protect her daughter from bad luck. Robe (details), 1800–1942. Palestine. Linen, silk; embroidered, 51 1/2 x 53 1/2 in. (130.8 x 135.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of the Estate of Mr and Mrs. F. J. Shepard, 1942 (C.I.42.176.1). Photos by Elena Kanagy-Loux

The al-Khalil region (Hebron)[16] has a rich cultural heritage that includes densely embroidered women’s garments with tiny colorful cross-stitches and elaborate silk appliqué. Each thobe expresses a passionate attachment to the crops the villager cultivated and to the soil, sea, and rivers of their homeland. Al-Khalil is located south of Bethlehem and is one of the oldest continuously inhabited parts of Palestine.[17] The area is named after Abraham, or Khalil Al Rahman, who is said to be buried in Al Haram Mosque, a holy site of pilgrimage for Jews, Christians, and Muslims. In the nineteenth century, the local population subsisted on agriculture and trade, and craftsmen as early as the ninth century had become known for their glassblowing of colorful lamps, cups, vases, bracelets, and beads.[18, 19] It is believed that the ingredients used in the glass included Dead Sea sand from the quarry of Beni Na’im, a village in eastern al-Khalil, creating a unique composition that is different from glass made elsewhere in the region.[20] Beads offer a new avenue of research into the wider material culture of Palestine and the overall study of adornment. Most often, they are found in traditional headdresses and jewelry, but in special circumstances, a Palestinian woman or girl stitched beads into the tatreez, such as in the Ramallah youth thobe in The Met collection, providing rare insight into the personality of the maker.

Late nineteenth century embroidered fragment from an al-Khalil thobe, using handwoven indigo-dyed linen ground cloth with cross-stitched patterns using silk threads. All patterns are associated with the al-Khalil area and are referred to as (from left to right) Moon of Beni Na’im, a variation of Pasha’s Tent, Star of al-Khalil and the Cypress Tree.[21, 22, 23] From the author’s collection

In 1946, demographic records indicate that al-Khalil comprised eighty-three towns and villages, with an Arab population of approximately 100,000 people. The women of al-Khalil primarily used the cross-stitched embroidery pattern called the “Tent of Pasha,” with variations that were specific to each village or town, and each dress style expressed distinct compositions of patterns and colors, all using silk threads.[24] Most of the tatreez patterns on the dresses capture the natural landscape and agricultural life of the al-Khalil region, including geometric flowers, cypress trees, feathers, and rosettes—reflecting their centuries-old relationship to the land, celebrated and remembered through each stitch on their thobe.

A traditional ceremonial dress style from a village located between al-Khalil and Yaffa, produced during the early twentieth century. Typically the dresses of al-Khalil are heavily embroidered with cross-stitch on the chest panel, skirt sides, and back panel. The colorful taffeta and other silk fabrics are used for appliqué and are also often embroidered. From the author’s collection

A woman’s ensemble from al-Khalil during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries often included the heavily embroidered dark linen thobe with cross-stitch embroidery and silk appliqué, worn with a large embroidered ghudfeh (scarf) and taqsira (short-sleeved jacket). There were two main headdresses: one for everyday wear, called an eraqiyyeh, and one for a bride for her wedding, known as the wiqayat al-diraham (or “money hat”).[25] Each headdress was ornamented with silver coins from the many empires that ruled and influenced the region, including Maria Theresa dollars (Austrian, minted between 1740–80 CE) and British Mandate currency (minted between 1927–47 CE), as well as various Islamic, Greek, Roman, Byzantine, Russian, and Egyptian currencies.[26] Sometimes metal amulets were sewn onto the headdresses for good luck, and in the past century, lighter-weight, decorative brass coins featuring artistic designs were regularly attached to tourist-sold headdresses or perhaps due to the difficult financial conditions of the wearer.

Left: The author studying an eraqiyyeh headdress from the early twentieth century at the Tiraz Centre in Amman, Jordan during her fellowship year. Photo by Safa Ghnaim. Courtesy of Tiraz: Widad Kawar Home for Arab Dress collection. Right: The same eraqiyyeh headdress features 30 coins and 3 beads, including a Maria Theresa coin (dated 1780), 19 Ottoman Empire coins (dating from the reign of Abdülhamid II, 1293 Islamic/1876 Gregorian and Muhammad V, 1327 Islamic/1909 Gregorian), and several coins that were too worn to read. There was one blue bead on the top of the Maria Theresa coin, to protect from the evil eye, and two black beads. Courtesy of Tiraz: Widad Kawar Home for Arab Dress collection

While the thobe reflects the regional and social identity of the wearer, prior to the mid-twentieth century, the coins that adorned headdresses often drew from a woman’s familial inheritance, her bridal dowry, the currencies of the land’s many empires, and even, perhaps, coins carried by travelers from their home countries.The headdresses are inherited generationally, with each wearer having the option to add a coin, bead, amulet, or medallion. The adornments are densely layered, yet on the al-Khalil eraqiyyeh, the embroidered pattern of the “doorway” encircles the edge of every cap, symbolizing good luck with colorful vibrancy next to the silver glistening coins.[27]

Detail image of the “doorway” pattern in cross-stitch embroidery on the cap of the same headdress. Every al-Khalil headdress is embroidered with this motif. Side-by-side, the top of the doorway pattern appears in a zigzag formation that represents running water, which is a symbol of good luck. Courtesy of Tiraz: Widad Kawar Home for Arab Dress collection

Al-Nakba, Arabic for “the catastrophe,” recognizes the ethnic cleansing of Palestine—the depopulation of 418 Palestinian villages and the resulting displacement of 750,000 Palestinians between 1947 and 1950 during the creation of the state of Israel.[28] During al-Nakba, family heirlooms, including dresses, were looted from the homes of families who fled for safety with nothing but the clothes on their back, counting on the promise that they could return to their locked homes after the war. While donor acquisition records for Palestinian dresses are significantly lacking, the decade in which many were donated to museums corresponds with wars and other tragedies in Palestinian history.

The profound and lasting impact of al-Nakba significantly transformed embroidery and dressmaking traditions for women who became newly displaced refugees in villages not yet destroyed or in the neighboring countries of Lebanon, Jordan, and Syria.[29] During the 1950s, very few traditional dresses were produced as Palestinians “found themselves living and working under utterly different political exigencies, in transformed and difficult environments, with changed material realities.”[30] The geographically specific embroidery and dressmaking techniques were no longer practiced, as women began sharing their patterns with one another amid the diverse and displaced populations now living in refugee camps. Many Palestinian women could no longer afford the specialized supplies required for tatreez, or the silks, beads, and coins that adorned the thobe. Nor could they find the traditional fabrics from the historic Gaza weaving center of al-Majdal, whose inhabitants were forcefully displaced to the present-day Gaza Strip where they attempted, time and again, to revive their centuries-old weaving practices with the looms they had saved. Over the past nine months, the historic looms of al-Majdal have been destroyed; the weavers’ fates are unknown.[31]

The six-branch dress (1950s–1960s). The style was named for the vertical embroidered panels (aruq, or branches) in the skirt. Despite being one of the oldest styles in the region, after 1948, Palestinian women began embroidering curvilinear floral patterns into the thobe that reflected their state of exile, not through specific motifs but in the lack of the symbols’ connections to specific villages and towns in historic Palestine. The thobe no longer communicated a regional identity, but a national one. From the author’s collection

The six-branch dress, named for the embroidered panels in the skirt, is one of the oldest styles in the region, produced well into the early twentieth century using motifs and cuts that followed traditional village styles. The revival of the style after 1948 marks the emergence of the first thobe that used curvilinear floral patterns not tied to a specific village or town, symbolizing a Palestinian national consciousness that developed beyond borders.[32] The six-branch dress followed a shawal silhouette, featuring a simple tailored cut and narrow sleeves that was easier for women to sew in the refugee camps, and embroidered on the chest, sleeves, as well as in four to six vertical panels in the skirt.[33] The six branches allowed women to embroider thin panels when times were difficult and they could not afford the luxury of embroidery threads, thickening them as their circumstances improved.[34]

The origins of the Initifada thobe are less known, however it is said that this garment was designed by Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat’s wife, Suha, during the First Intifada. ANAT Workshop for Arab Heritage in Damascus, Syria, an embroidery cooperative in the Palestinian refugee camps, later acquired the thobe and began to use it as a model for their Intifada dresses. Dress. Palestinian, late 20th century (TRC 2003.0007). Courtesy of the Textile Research Centre, Leiden

During the first major Palestinian uprising, also known as the First Intifada (1987–93), women responded to severe curfews, increased home demolitions, and the banning of the Palestinian flag by embroidering explicitly nationalistic motifs onto their dresses using the colors of the flag: red, black, white, and green.[35] For the first time, tatreez ornamenting the thobe included men wearing the keffiyeh scarf and slinging rocks, protest chants in calligraphic script, and the borders of historic Palestine. Palestinian women were determined to pass the art of embroidery to their daughters in the diaspora, teaching them how to deploy the language of tatreez on their thobe to tell their story of resistance and existence under Israeli military occupation.

Before 1948, land was central to Palestinian life; agricultural customs served as seeds for local cultural practices as a whole. Each villager cultivated a sense of self in relation to their village, and these localized traditions made any separation from land an obliteration of self. During the first few years of displacement, Palestinian refugees—now, landless farmers—used metaphors such as “death,” “burial,” and “non-existence” to speak of their dispossession. Today, the older generations still mourn as they recall their exile that began seventy-six years ago, using the same word for pilgrimage to Mecca, hajj, to describe their visits to Palestine.[36] In this context, one must ask, if Palestine holds the collective memories of the Indigenous people, then what is the significance of the thobe when she is far from her land, stripped from her maker?

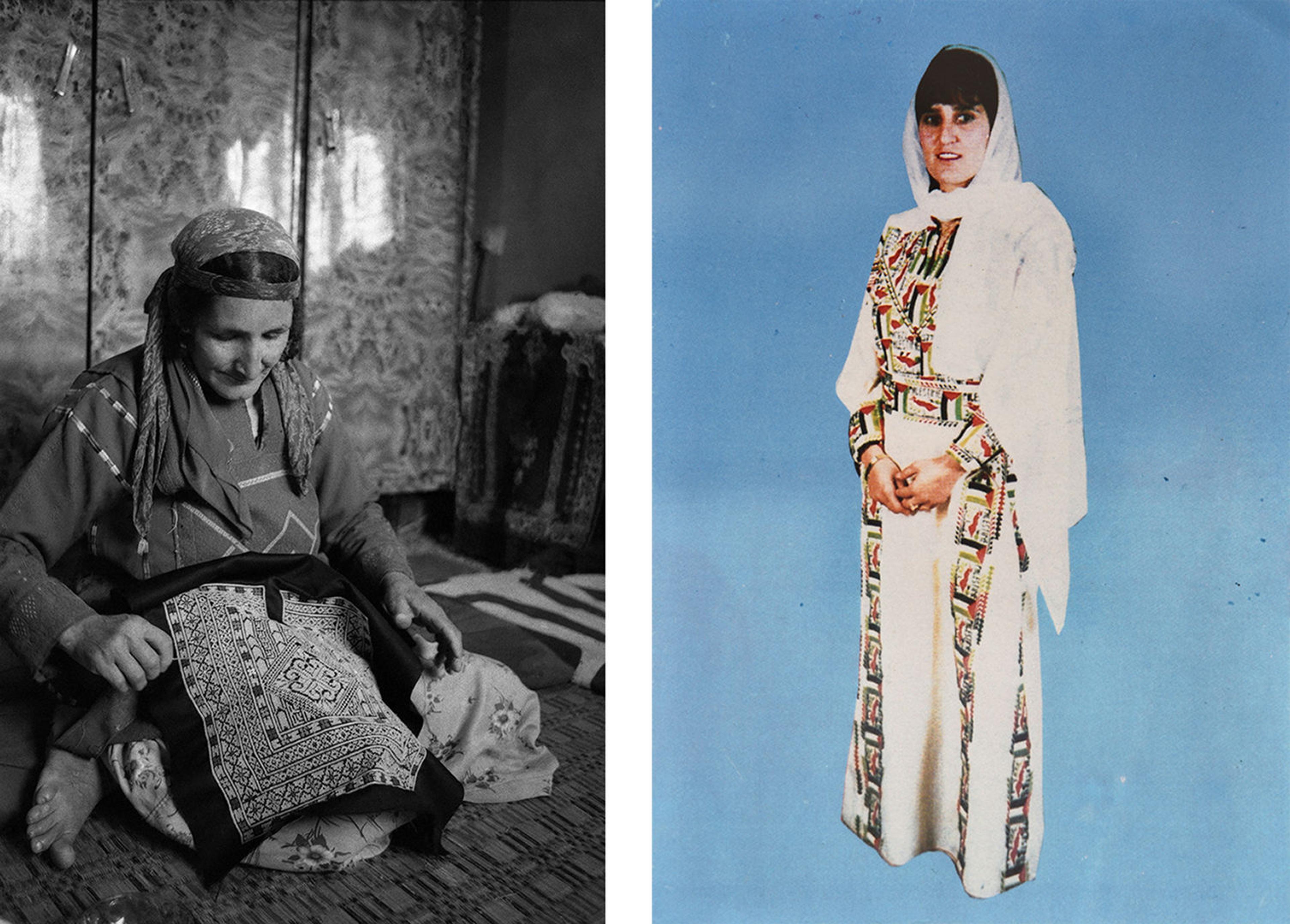

Left: Um Adnan is embroidering and wearing a shawal-style Palestinian thobe in al-Mazra'a ash-Sharqiyya, a village in Ramallah. The photograph was taken in 1988, during the First Intifada, showing the daily activities of women who were subjected to round-the-clock curfews imposed by the Israeli army that forbade Palestinians from leaving their homes, for days, weeks or at times, months on end. The embroidered chest panel she wears was a common style of the 1970s–1980s, while the chest panel she embroiders reflects styles worn in the 1980s–1990s. Um ʿadnan Embroidering a Palestinian Thobe in al-Mazra'a ash-Sharqiyya Town, 1988. Joss Dray. Courtesy of the artist © Joss Dray. Right:A Palestinian woman wearing the “flag dress” or thobe al-intifada for a postcard produced by As-Sanabil Center for Studies and Popular Heritage Collection (1990s). Palestinian Museum Digital Archive

While the thobe once represented the maker’s regional identity, illustrated through embroidered patterns, colorful threads, coins, beads, and adornments, the dress has now evolved as a symbol of national identity, cultural survival, and evidence of Palestinian life persisting against all odds. The preservation of Palestinian embroidery and dressmaking traditions has triumphed in the face of violence, war, and occupation because it is a living art form, encoded with stories of the land and its people, even when they have been separated. Today, the thobe merges both traditional and contemporary tatreez symbols to document the maker’s biography within a new material and sociopolitical reality of Palestinians in exile, operating as a proxy for land and serving as a prolific creative medium to envision freedom and grasp on to hope in what, at times, appears to be a hopeless world.

The author would like to express deep gratitude to her mother, Feryal Abbasi-Ghnaim, who taught her the history, techniques, and culture of Palestinian embroidery and dressmaking traditions, which influenced her life’s work from a young age. The author was immensely inspired when, in 2018, her mother was awarded the National Endowment for the Arts National Heritage Fellowship as the first-ever Palestinian woman and embroiderer to receive the prestigious lifetime achievement award. The author is also sincerely thankful to Widad Kawar, Mary Kawar, Salua Qidan, and Ruba Thaher of Tiraz: Widad Kawar Home for Arab Dress & Textile Museum, who have been instrumental in her growing body of work to preserve Palestinian and Syrian embroidery and dress in the United States. The author credits her elders—Widad Kawar, Hanan Munayyer, Maha Saca, and her mother—pioneers in cultural heritage preservation who have empowered her through their extensive publications and generous mentorship. It is thanks to the resilience of these Palestinian women that the author has found a renewed sense of hope and strength.

Notes

[1] Zaatar is a spice mixture that is either based in thyme, oregano or originally, origanum syriacum, and includes toasted sesame seeds, dried sumac, salt, as well as other spices. Here, the author references the thyme plant growing from the soil, not the spice mixture.

[2] “What color are you?” is used as a greeting in the dialect of Palestinian villagers, who are asking, “How are you?”

[3] The United Nations defines “Indigenous” as communities, peoples and nations who have “historical continuity with pre-invasion and pre-colonial societies that developed on their territories” and “consider themselves distinct from other sectors of the societies now prevailing on those territories, or parts of them.”

[4] J.B. Barron, “Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922, Taken on the 23rd of October, 1922” (British Mandate Report).

[5] Shelagh Weir, Palestinian Costume (Northampton: Interlink Books, 1989), 16.

[6] Widad Kamel Kawar, Threads of Identity: Preserving Palestinian Costume and Heritage (Cyprus: Rimal Books, 2011), 1.

[7] Walid Khalidi, All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948 (Beirut: Institute for Palestine Studies, 1992), xxxiii.

[8] UNESCO inscribed the art of embroidery in Palestine, encompassing the practices, skills, knowledge, and rituals, on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity during the 2021 (16.COM) session.

[9] Issam Nassar, “‘Biblification’ in the Service of Colonialism,” Third Text 20, no. 3–4 (2006): 317–326, https://doi.org/10.1080/09528820600853589.

[10] Vogue, New York, 5, no. 21 (May 23, 1895): v.

[11] Nassar, “‘Biblification’ in the Service of Colonialism,” 317–326.

[12] Since 2020, Wafa Ghnaim has shared her knowledge and research, culminating in part with her fellowship project in 2023–2024 to update the attributions of the Palestinian and Syrian dress collections in the Department of Islamic Art.

[13] Iman Saca, Embroidering Identities: A Century of Palestinian Clothing (Chicago: The Oriental Institute Museum of the University of Chicago), 36.

[14] Hanan Karaman Munayyer, Traditional Palestinian Costume: Origins and Evolution (Northampton: Olive Branch Press, 2020), 108.

[15] Karaman Munayyer, Traditional Palestinian Costume, 114.

[16] During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, both place names “al-Khalil” in Arabic and “Hebron” in Hebrew were used. Both are interchangeably used by Palestinian historian Walid Khalidi, in “All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948” (1992) Institute for Palestine Studies, Washington DC.

[17] Vogelsang-Eastwood, Encyclopedia of Embroidery from the Arab World, 370.

[18] Karaman Munayyer, Traditional Palestinian Costume, 372.

[19] Gusta Lehrer, Hebron City of Glassmaking (Tel Aviv: Museum Haaretz, 1970).

[20] This is according to oral history interviews conducted by the author between 2020 and 2023 with Palestinian elders.

[21] Margarita Skinner, The Journeys of Motifs: From Orient to Occident (Cyprus: Rimal Books, 2018), 237.

[22] Margarita Skinner, Palestinian Embroidery Motifs: A Treasury of Stitches 1850-1950 (Cyprus: Rimal Books, 2007), 168–172.

[23] Nabil Anani and Sliman Mansour, Guide to the Palestinian Art of Embroidery (Amman: Inaash Al-Usra Association and Al Abliyya Publishing, 2011), 36.

[24] Kamel Kawar, Threads of Identity, 109–111.

[25] Weir, Palestinian Costume, 184.

[26] The author would like to express sincere gratitude to Deniz Beyazit, curator in the Department of Islamic Art, who taught her how to read currency coins found on Palestinian garments and provided support for the author’s research of the Palestinian and Syrian dress collections at The Met. The author would also like to acknowledge the guidance and contributions of Federico Caro in the Department of Scientific Research, Eva Labson in the Antonio Ratti Textile Center, and Kim Benzel in the Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art, who have supported the author’s research on headdresses and adornment in Palestine during her fellowship year.

[27] Karaman Munayyer, Traditional Palestinian Costume, 402.

[28] Khalidi, All That Remains, xxxiv.

[29] United Nations Relief Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East. https://www.unrwa.org/where-we-work Accessed on June 6, 2024

[30] Rachel Dedman, At the Seams: A Political History of Palestinian Embroidery (Birzeit: The Palestinian Museum, 2016), 44.

[31] This information was provided directly to the author by Husam Zaqout, a descendent of one of the main families of al-Majdal, who was located in Gaza at the time of the correspondence and witnessed the destruction by the Israeli occupation on November 28, 2023. Before October 7, 2023, Mr. Zaqout had a weaving business, making and selling the special Majdal fabrics on the historic looms, employing local weavers, and teaching the tradition of weaving at Atfaluna Society for Deaf Children to provide income-generating activities to the deaf Palestinian community in Gaza. His heroic efforts to protect Palestinian cultural heritage have continued in Cairo, where he is rebuilding his weaving center.

[32] Dedman, At the Seams, 44.

[33] Weir, Palestinian Costume, 274.

[34] Weir, Palestinian Costume, 273.

[35] Dedman, At the Seams, 65.

[36] Rosemary Sayigh, Palestinians: From Peasants to Revolutionaries (London & New York: Zed Press, 1979), 109–110.