The city of Spina

During the Classical period (fifth–fourth century BCE) in the Greek city of Athens, artisans specialized in the art of finely painted pottery decorated with figurative scenes, creating a marvelous world of shapes and images for their customers. On the vases’ surfaces, the scenes appear in the orange-reddish tones of the clay and are surrounded by a painted shiny black gloss creating the background. This type of pottery is called red-figure, and it was mainly, but not only, used for wine-drinking ceremonies called symposion.

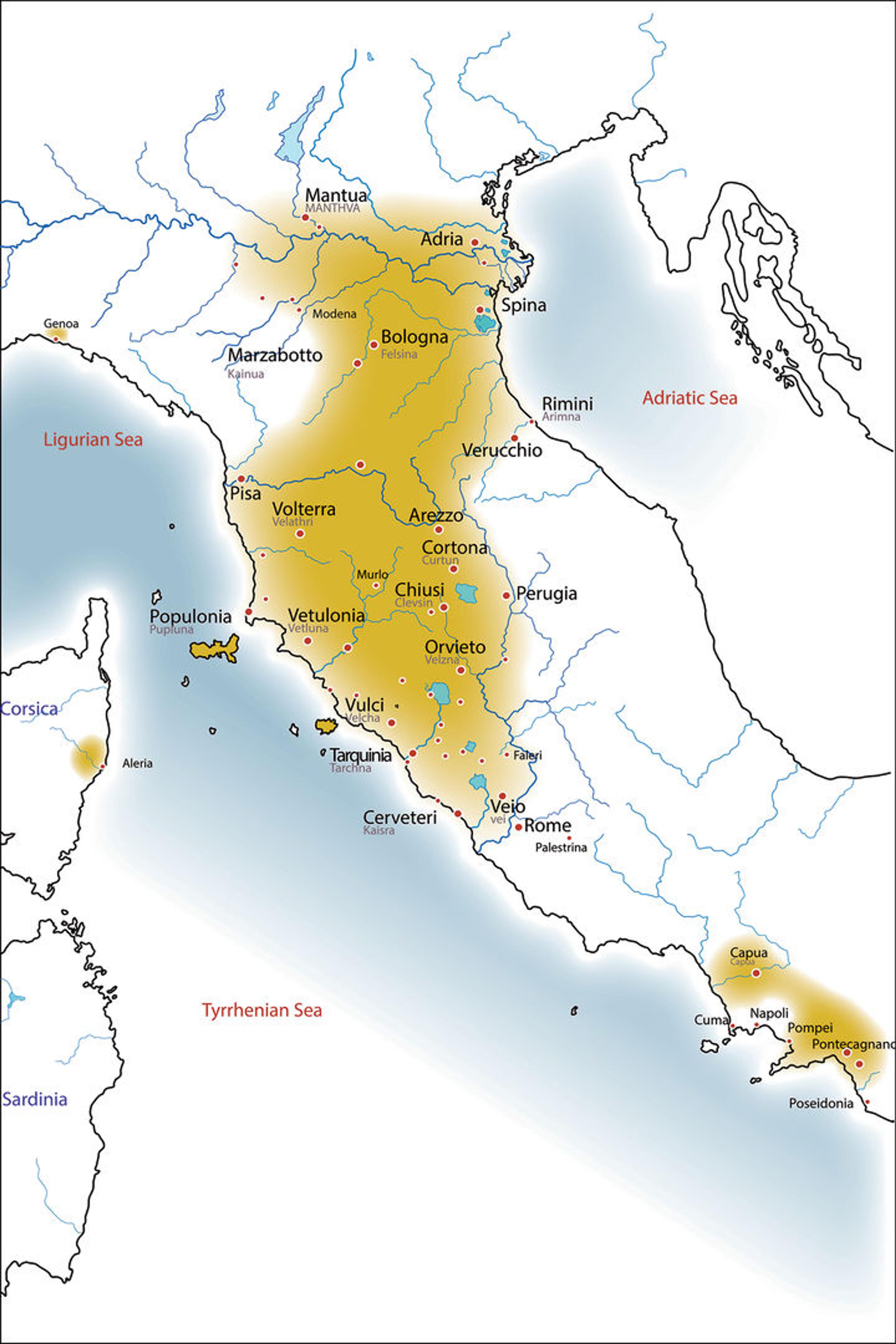

Despite these vases being used locally in Athens, many have been found outside Greece, around the Mediterranean and beyond. The majority were discovered in Etruria, the land of the Etruscans, a pre-Roman people located in the central and northern regions of the Italic peninsula.

Map of central Italy with the Etruscan regions in dark yellow. Main cities (known Etruscan names in gray) and sites are marked by red dots. Studio Kiro, Bologna with modifications

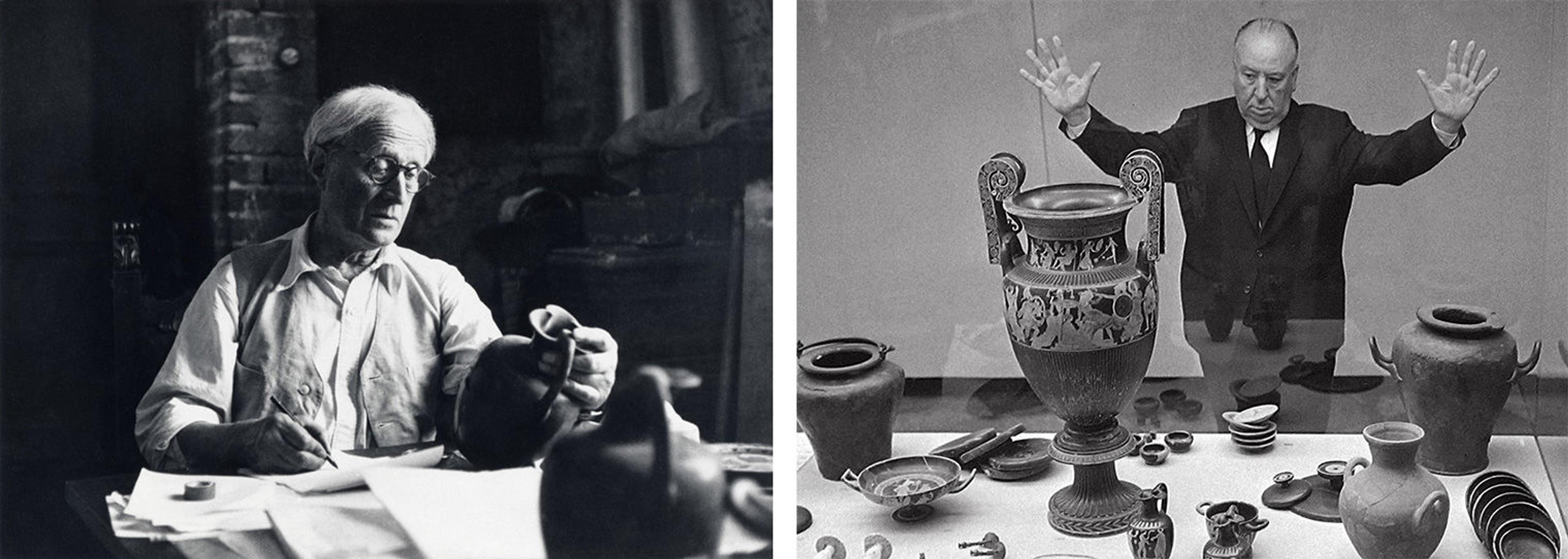

Settled on the northern shore of the Adriatic, the Etruscan city of Spina was one of the favored destinations for the trade of Attic pottery during the fifth and fourth centuries BCE. One of the foremost scholars to study Athenian vases, Sir John Davidson Beazley, was convinced that the Museum of Ferrara, with its collection from Spina, had the largest and most important collection of red-figure pottery in the world.

Left: Sir John Beazley cataloguing an unidentified vase in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Ferrara, Autumn 1956. Photo by “Prof. Alfieri” (presumably Nereo Alfieri, Italian, 1914–1995). Image courtesy Beazley Archive, Classical Art Research Centre, University of Oxford Right: In October 1960, the director Alfred Hitchcock, visiting the exhibition dedicated to Spina in Bologna, was astonished by Athenian vases found in Etruscan tombs and could not resist the temptation to pose behind one of the showcases. Image © ARCHIVO FOTOGRAFICO STORICO "FOTOWALL" di WALTER BREVEGLIERI, edizioni Minerva, Bologna

During the twentieth century, the thousands of Athenian vases being excavated in Spina attracted the attention of numerous experts. Like Beazley, however, they remained mainly focused on the study of painted styles and on the interpretation of their iconography solely from the Athenian point of view, forgetting the Etruscan context and users of these objects. At the dawn of the twenty-first century, some scholars began questioning this focus on Greece, and especially Athens. New studies were dedicated to a better understanding of ancient international trade involving the massive exports of Athenian pottery to Etruria, as well as the uses, functions, and meanings of these objects and their images for Etruscan buyers. That research has revealed more complex patterns in this market. Specific vase shapes, iconographies, and even the production from specific Athenian workshops targeted determined regions and cities, responding to local buyers’ tastes. There is also growing evidence of individual commissions of vases (both in terms of shape and painted subject) from locals like the Etruscans for special private use.

The magnificent volute-krater (440–430 BCE), a big container for mixing wine and water, on loan at The Metropolitan Museum of Art from the Archaeological National Museum of Ferrara reflects these developments in contemporary research and most probably constitutes one of those special commissions from an individual Etruscan to the famous workshop of Polygnotos in Athens. Because of its unique painted scene, it has been the object of dozens of publications reflecting both Atheno-centric and contextual approaches. The vase was discovered in one of the most important graves of Valle Trebba, Spina's cemetery: tomb 128. The scene painted all around its body, its association with the other grave goods, and the location and structure of the tomb itself, offer an excellent journey into the (Under)world of the Etruscans.

Red-figure volute-krater from tomb 128 of Spina. Terracotta volute-krater, 440–430 BCE. Greek, Attic, Classical Period. Terracotta, 26 x 16 5/8 in. (66 x 42 cm). Lent by the Republic of Italy, Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Ferrara (L.2023.30)

City of the dead

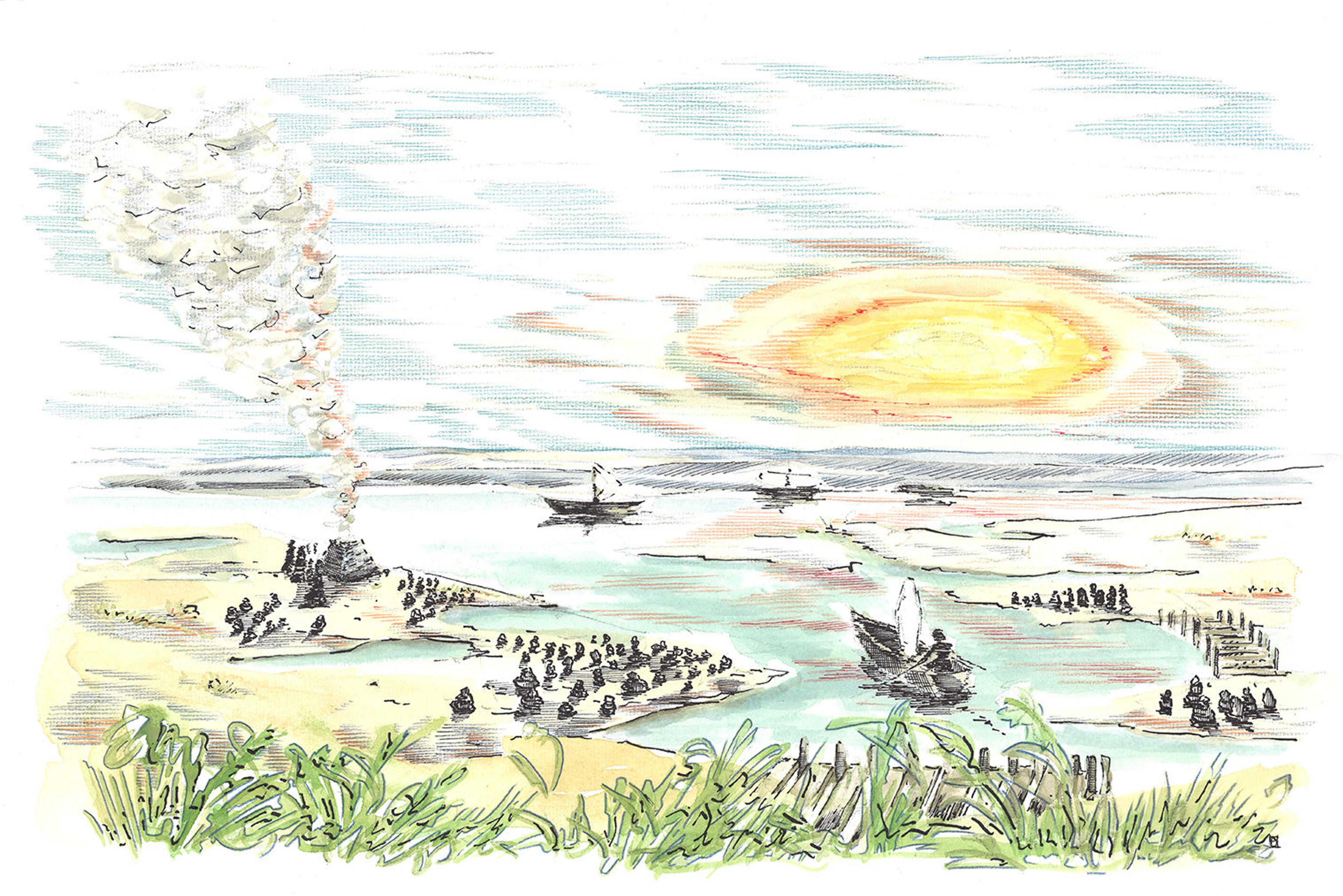

Before exploring the contents of tomb 128, where the volute-krater was discovered, one should picture the atmosphere of Spina’s cemetery (Valle Trebba and Valle Pega) at the time of the Etruscans: a vast and misty lagoon with calm water channels dividing the funerary areas, with the graves clustered at the top of elongated sandy mounds. The channels run parallel to the coast, between the settlement and the sea, the city of the dead reflecting the one of the living on the other side of the broader channel. The members of Spina’s community had to navigate on small boats to reach the graves of their beloved.

Artistic reconstitution of the necropolis in Spina. Watercolor by Peter Depelchin, 2024

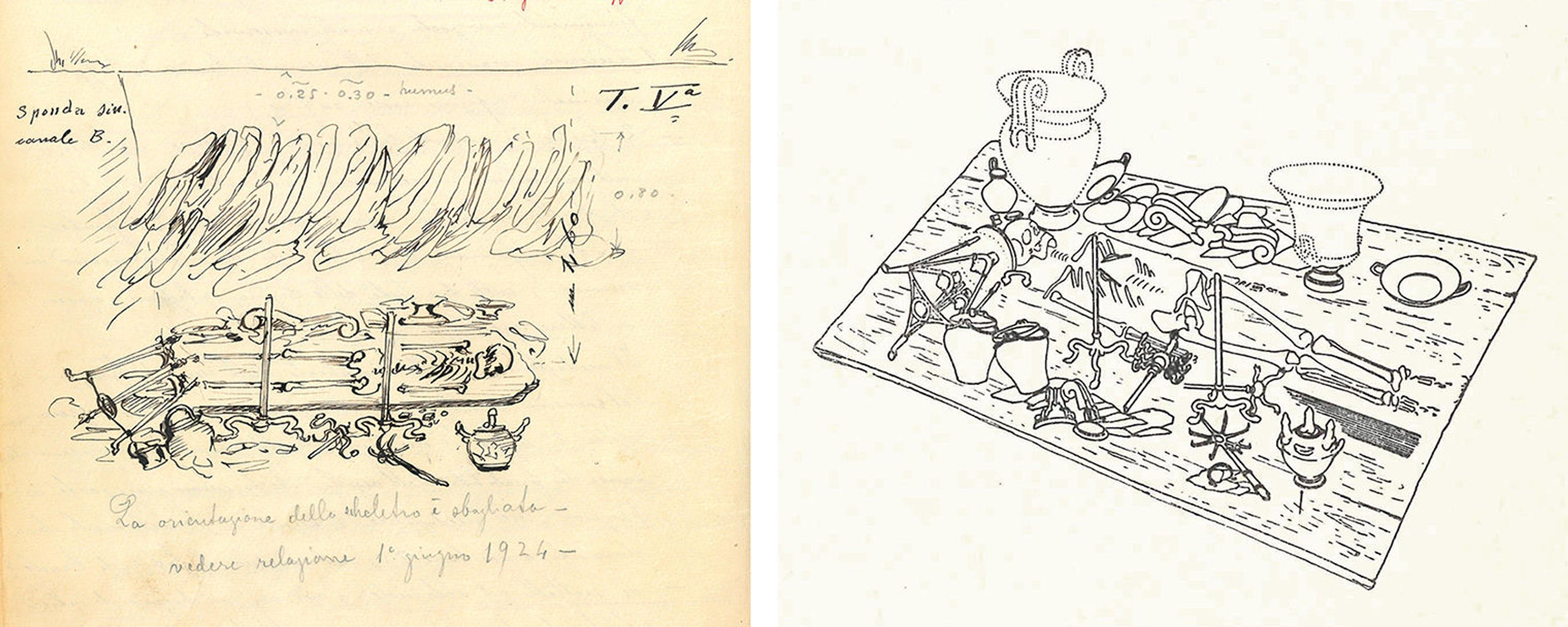

Tomb 128 represents one of the most important graves in Spina’s necropolis and in the Valle Trebba locality. The tomb was excavated in an isolated area, without any graves around it. In the necropolis, this way of isolating a grave (leaving a wide space around) marks the special respect due to the deceased by Spina’s spura—the urban community in the Etruscan language. More features displayed the rank and the relevance of the person buried in tomb 128: it was the only grave in the cemetery that had been filled with a massive rock layer and possibly covered with a carved stone stele. And within the tomb were three large kraters: the one on loan at The Met, another red-figure calyx-krater, and the surviving magnificent handles and foot of a bronze volute-krater.

Left: Excavation of tomb 128. Sketch by the archaeologist Francesco Proni, June 1, 1924. Image courtesy Direzione Regionale Musei Emilia Romagna, Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Ferrara Right: Graphic reconstruction of tomb 128. From S. Aurigemma, La necropoli di Spina in Valle Trebba, Roma, Ed. L'Erma di Bretschneider, 1960

An enigmatic scene

The volute-krater from tomb 128 of Valle Trebba, exquisite in proportions and design, is a unique masterpiece painted around 440–430 BCE in Athens by an artist who was a follower of the famous vase-painter Polygnotos. The artist created a new type of scene, without any comparison in the whole panorama of Athenian red-figure pottery. At the center of the body, two royal figures sit on thrones within a building defined by two columns. Both hold a scepter and a kind of flat bowl called a phiale, used in ancient times to pour liquid offerings (libations). In fact, although it has almost disappeared today, we still can see a whitish line falling from each phiale down to the ground, down to the Underworld. The male figure has snakes around his head, and his female consort has a lion perched on her left arm. A tiara crowns her beautiful head.

Four views of the volute-krater from tomb 128 at Spina. Terracotta volute-krater, 440–430 BCE. Greek, Attic, Classical Period. Terracotta, 26 x 16 5/8 in. (66 x 42 cm). Lent by the Republic of Italy, Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Ferrara (L.2023.30)

The iconographical scheme—body position, gesture, and the couple itself—reveals that they are gods and rulers. The presence of the building projects the scene in the Underworld, Hades’ House mentioned by Homer. Many peoples in the ancient Mediterranean were able to read this image thanks to a rigid code common to producers and consumers of Athenian pottery and other crafts.

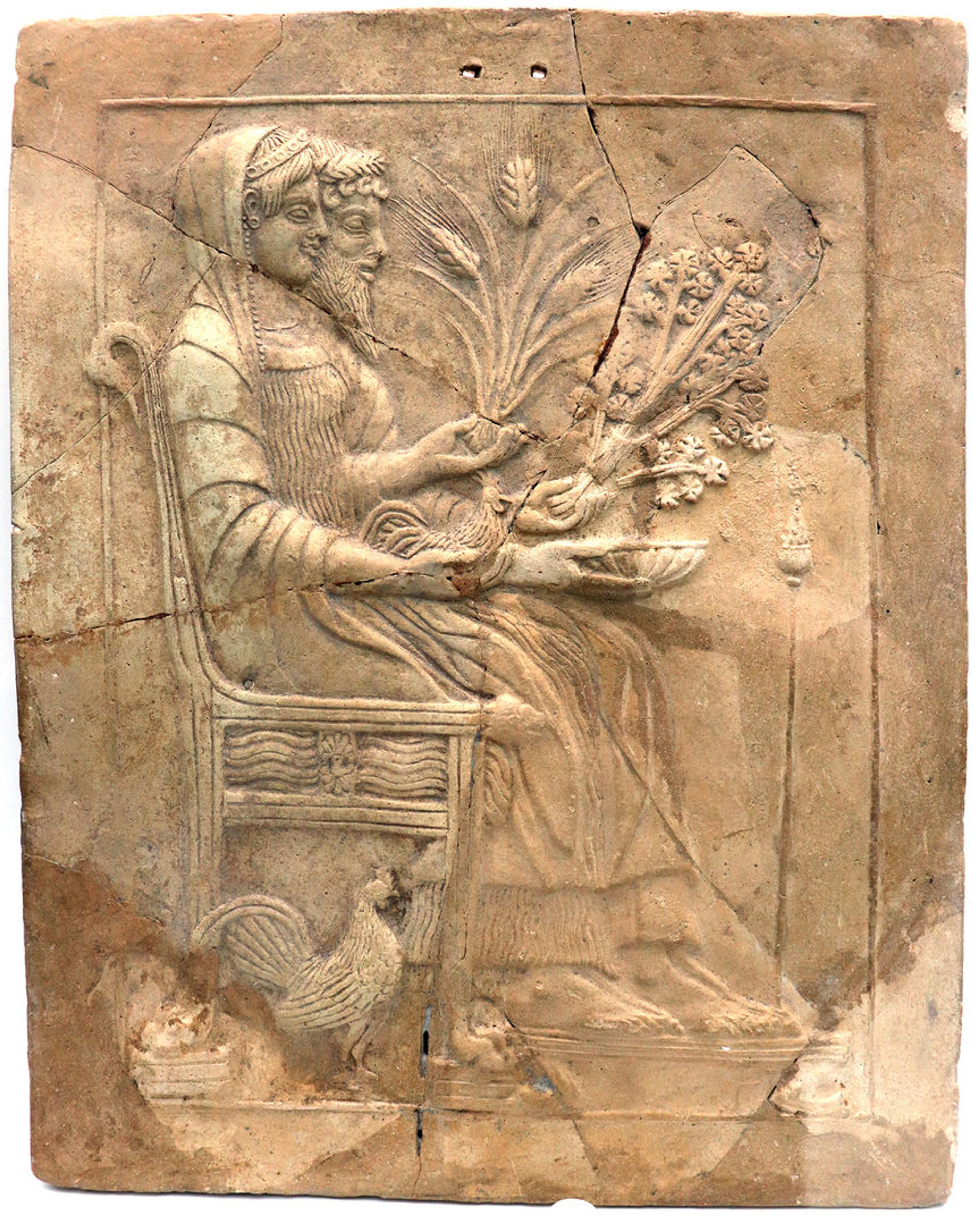

Terracotta Pinax (votive plaque) representing Hades and Persephone enthroned. Hades holds a phiale. From Epizephyrian Locri, first half of the 5th century BCE (inv. Z 8/31). Su concessione del Ministero della cultura – Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Reggio Calabria

In front of these deities stands an altar with wooden branches ready to be lit. Behind the altar, a procession of three women converges toward the gods. First, a white-haired priestess approaches, holding something veiled or hidden on her head: a sacred basket called a liknon in ancient Greek. The priestess is followed by two women, one playing the double aulos (flute), the other with a tympanon (tambourine). The rest of the scene depicts an ecstatic dance performed in honor of these deities, with musicians playing flutes, tambourines, and cymbals. The thirteen dancing figures comprise adult women and men, youths, girls, and toddlers. Most are holding snakes in their hands or wear them around the head; some throw their heads and busts backward in ecstasy, their mouths slightly opened, the drapery of the dresses flying around their bodies.

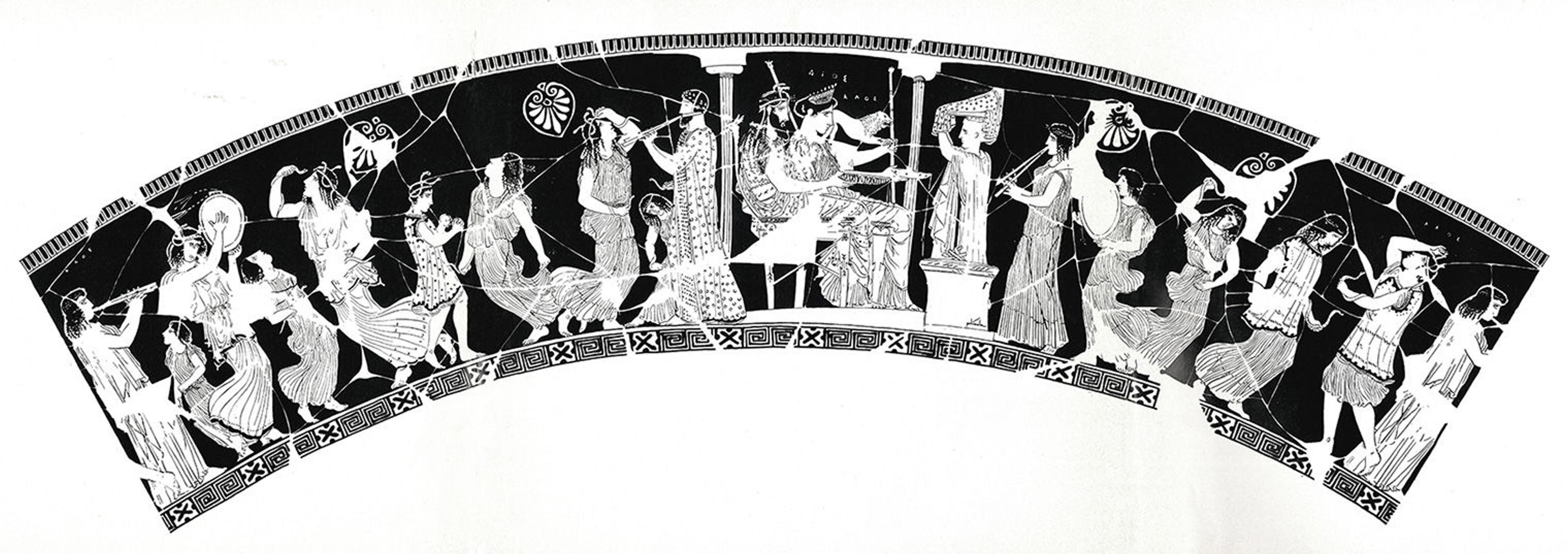

Top: Terracotta volute-krater (details of the divine couple and the priestess), 440–430 BCE. Greek, Attic, Classical Period. Terracotta, 26 x 16 5/8 in. (66 × 42 cm). Lent by the Republic of Italy, Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Ferrara (L.2023.30) Bottom: The scene on the volute-krater. Drawing: Gino Pelizzola. From SPINA: dai disegni di Gino Pelizzola, Arti Grafiche Tamari, Bologna, 1967

By 1983, at least thirty-two papers had already been written about the difficult interpretation of this mysterious scene. The main question was the identification of the divine couple represented at the vase’s center. Most scholars agreed on a few points: First, the male god and the scene around him allude to Dionysos and to some Dionysiac mystery cult because of the sacred basket on the priestess’ head; the type of instruments (tympanon, flute, cymbals); the dance and its ecstatic (wine-intoxicated?) character; and finally because of the krater’s shape itself, used for mixing wine and water. Despite these elements, it is not the usual Greek Dionysos—and here, most studies forget the composition specific to Hades and the funerary aspects of the krater. The absence of common symbols associated with Dionysos—an ivy or vine wreath, a thyrsos (a sort of scepter, one of his main attributes), a satyr (a mythological part-man part-goat creatures), or a wine-drinking cup—makes it difficult to immediately identify the figures. The representation of the god remains ambiguous, between Hades and Dionysos. Second, the scene is not mythological, and, besides the gods, it represents real people and worshippers in a cultic or liturgical context.

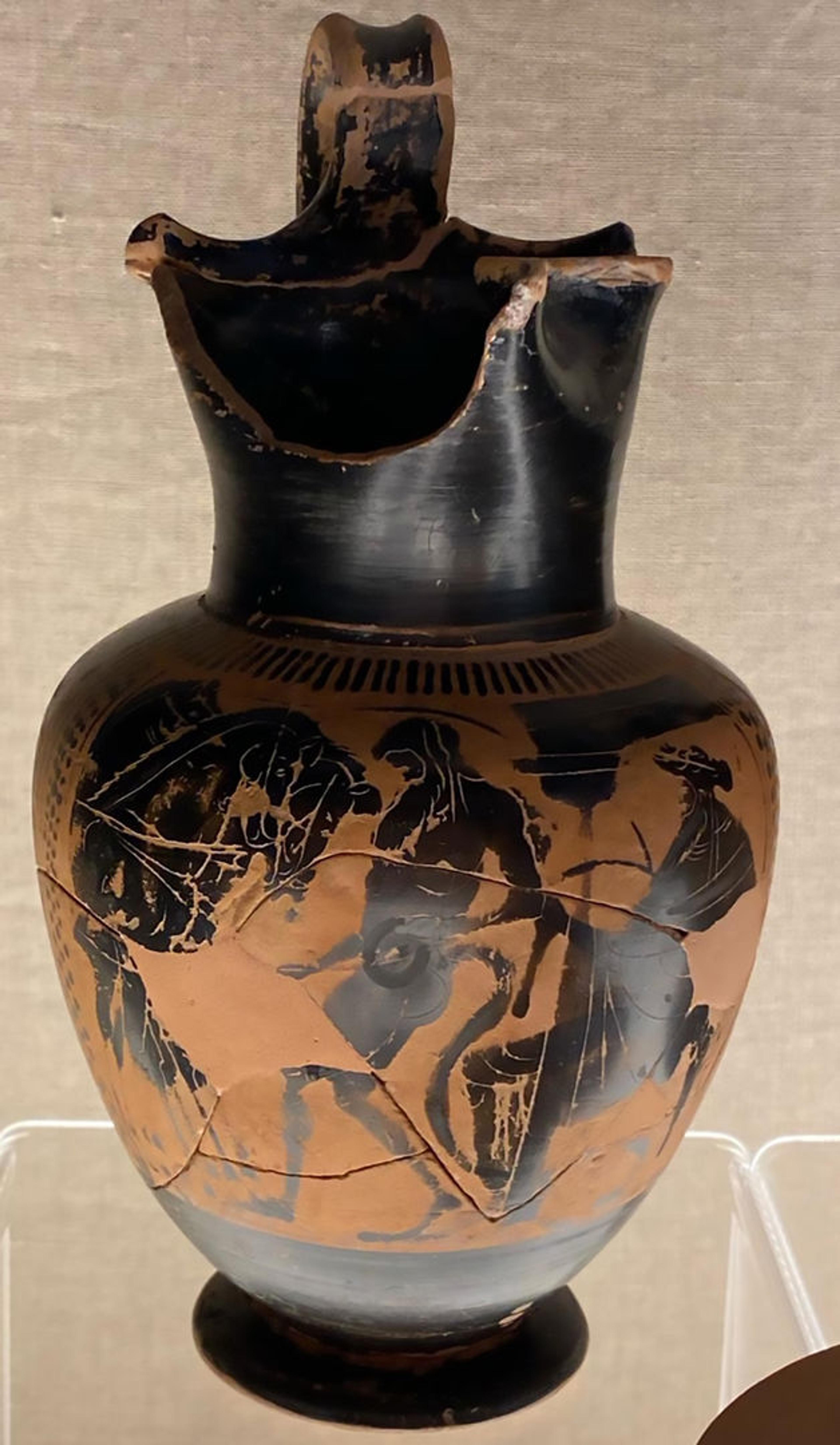

Women preparing Dionysos’ festival: the god’s mask is placed in a basket, or liknon, here uncovered. Attic red-figure jug (chous), ca. 420 BCE. Hellenic National Archaeological Museum, Athens, inv. VS 318. © Hellenic Ministry of Culture / Hellenic Organization of Cultural Resources Development (H.O.C.RE.D.). Photo by Irini Miari

Among various interpretations, the most accepted and repeated was first proposed by the German scholar Erika Simon in 1954. According to this interpretation, the male god is Sabazios, an Anatolian (modern-day Turkey) divinity connected with Dionysos and Zeus, whose cult was imported to Athens; Aristophanes mentioned it for the first time in 422 BCE in his play The Wasps. The goddess is seen as the Great Mother Kybele, another Anatolian divinity, whose cult became quite popular in Athens. The problem with these interpretations is that they are mostly based on literature and not on iconographic or contextual comparisons. No other Attic (or non-Attic) representations help to consolidate Simon’s propositions. There is no contemporary tradition of representing Sabazios and Kybele in this way. Finally, the funerary character of the krater’s context and scene, reinforced by the snakes, but also by the Hades type of composition, is left unexplained.

A complete banquet set for the afterlife

In 1994, Paolo Enrico Arias, archaeologist of Spina’s necropolis, highlighted the fact that the Etruscan—and therefore non-Greek—context of the volute-krater was completely ignored by Simon’s interpretation. He noted that only the study of tomb 128’s contents could help understand this masterpiece of Attic pottery and the unknown adepts of the Dionysiac cult who were buried in Spina’s cemetery. This historical-contextual approach was developed in the early 2000s by the scholar Cornelia Isler-Kerényi and enriched with a topographic-iconographic approach to the cemetery, recently proposed by the archaeologist Chiara Pizzirani.

In addition to the three large kraters, many precious objects, some of which were already old at the time of the deposition, were laid down along both sides of the body in the tomb. The rest of the contents presented a rich set for banqueting and wine-drinking: terracotta and bronze vessels (cups, plates, basins, jugs, etc.); a precious bronze tripod and the utensils needed to illuminate the space in the Underworld such as candelabra, stands, and a torch holder. Objects decorated with figures (imported and local pottery, bronze decorations) evoke themes sacred to Dionysos and Persephone: the stand is decorated with a dancing girl holding krotaloi (a kind of castanet); satyrs are depicted on the jugs and on the tripod.

Contents of tomb 128 from Spina, Valle Trebba. From Aurigemma, La necropoli di Spina in Valle Trebba, Roma, Ed. L'Erma di Bretschneider, 1960

A unique Athenian vase imitates a common Etruscan shape: a globular pot with two handles called an olla or stamnos. This example has a most unusual pouring spout combined with a strainer to filter the liquid contained inside. Most extraordinarily, three erect phalluses modeled in clay were added on this vase’s lid and shoulder as a symbol of Dionysiac life power. All around the body, erotic scenes and satyrs were painted in red-figure.

Attic red-figure vase (stamnos) with erect phalluses, from tomb 128. Spina, Valle Trebba. Direzione Regionale Musei Emilia Romagna, Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Ferrara

Two oinochoai (jugs) are specifically designed for ritual use: the bodies are shaped as female heads. These vases were used to pour liquids on the ground in ceremonies dedicated to Persephone in several Etruscan sanctuaries. They were also frequently placed in tombs belonging to women devoted to the goddess. In tomb 128, other items seem to be particularly meaningful from a ritual perspective, although we are not able to decode their original value, such as fragments of vessels made of wax, probably used in funerary or religious rites.

Pair of Attic red-figure jugs (oinochoai) in the shape of a female head. From tomb 128 of the Valle Trebba necropolis, inv. 1896 and 1897. Direzione Regionale Musei Emilia Romagna, Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Ferrara

“All the barbarians dance my rites”

Although we will never know the Athenian artist’s intentions and models because of the uniqueness of the krater’s scene, we can get a good idea about what the Etruscan users of the vase saw in this picture. From the Etruscan perspective, the vase is not isolated at all. It is one of several fifth-century artworks, both purchased from Athens or produced in Etruria, revealing that, in the Etruscan mindset, the afterlife was perceived as a Dionysiac dimension of dance and joy.

From this angle, the vase depicts a Dionysiac dance celebrated in honor of Hades and his female partner. In this period, Hades and Dionysos were similar gods in the Etruscan religion, and both—or a combination of both—are represented as ruling the Underworld on various figurative artworks. On a black-figure oinochoe (jug) from tomb 125 in Spina (Valle Trebba necropolis), Dionysos—identified by his crown of ivy leaves, his drinking horn, and the satyr accompanying him—is represented like Hades, enthroned beneath a building. In Euripides’ Bacchae, Dionysos claims “All the barbarians dance my rites.” This was certainly true regarding the Etruscans of the Classical period, for whom the god’s promise of salvation and life after death was a widespread religious belief. Literary sources testify to the diffusion of the Bacchic/Dionysiac cult from Etruria to Rome, after it had been imported from Greece. This cult developed until the beginning of the second century BCE, when it was forbidden by the Roman power in the entire peninsula. However, it survived under various forms in Etruscan cities.

Black-figure oinochoe with three horses on the left, a satyr at the center, and Dionysos seated in a building on the right, from tomb 125 of the Valle Trebba necropolis, inv. 300. Direzione Regionale Musei Emilia Romagna, Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Ferrara

Considering this historical context, the volute-krater from tomb 128 might have been a special commission made for an Etruscan client interested in a specific shape and iconography to fit and express his or her personal (and local) religious belief. The Athenian painter answered the commission in using the iconographical schemes and models he had in his cultural background: composition specific to Hades (enthroned, sitting enshrined with his consort, and pouring libations), a Dionysiac ecstatic dance with snakes; an unusual (non-Athenian) atmosphere mingling worshippers of both genders and various ages. In this sense, it is not impossible that foreign divinities recently adopted in Athens inspired the image. The depictions, however, were informed more by what the painter knew and thought about their cults than from clear iconographic and artistic motifs. Given the special character of the commission, the volute-krater cannot find comparisons in Athens, while its imagery and shape are absolutely coherent from the Etruscan perspective. Regarding the abundance of snakes on the krater, it should be noted that the reptile is ubiquitous in Etruscan funerary art, holding a chthonic association and profoundly connected with death and rebirth.

Many aspects of tomb 128 and its wonderful krater remain unclear and mysterious. Nevertheless, this is one of the most distinctive graves in the necropolis with Athenian figured pottery, and the deceased individual buried in it must have been a major figure of his or her Etruscan community, perhaps a priest or a priestess. It can be hypothesized that he or she was initiated to an eschatological Dionysiac cult, widespread in Etruria. Elsewhere in the necropolis of Spina, the contents from a group of female graves, clustered in a limited area of the cemetery, seems to express the same religious beliefs, centered on Dionysos’ cult and the god’s mythical journey through death and back to life.

Spina at The Met

Visitors to The Met might be surprised to find that the monumental volute-krater from tomb 128 is not the only vase from Spina in the Greek and Roman galleries. From Gallery 150, where the krater is on view in its specially dedicated case, you can walk to Gallery 159 and see several vases made in Athens and found at Spina.

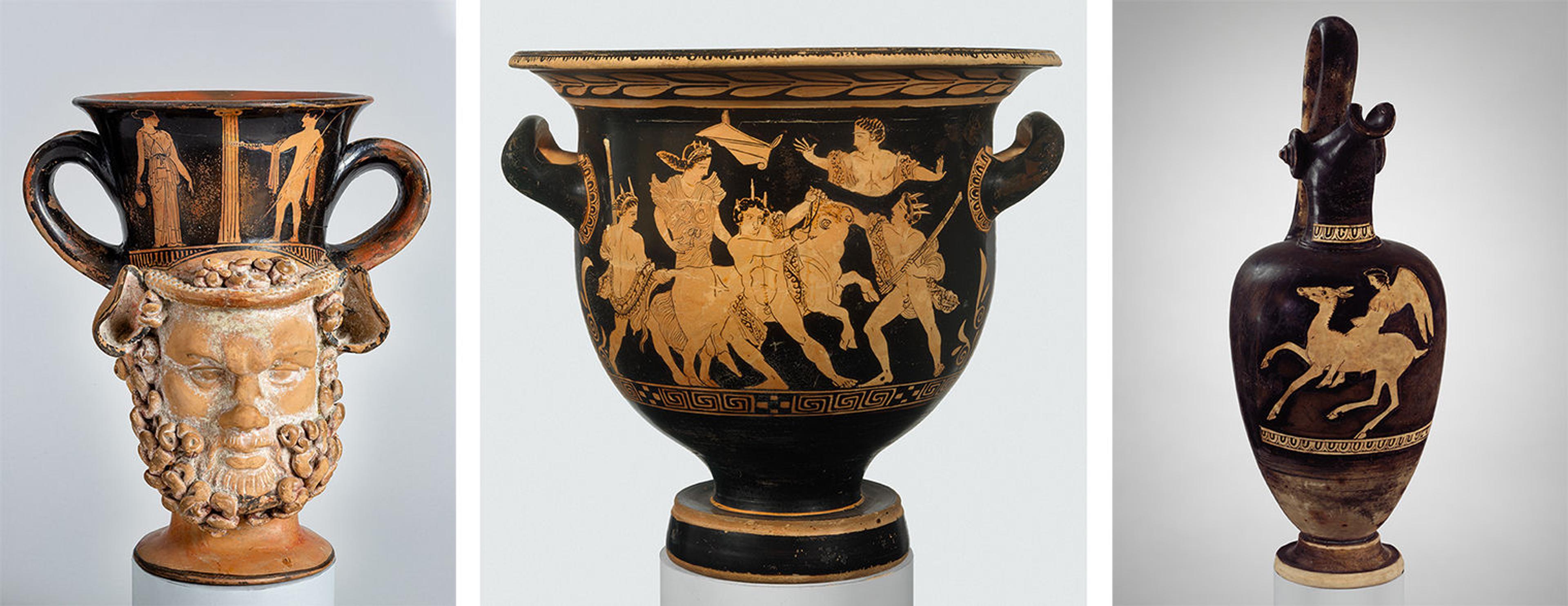

Left: Attributed to Aison and the Class V: The Spetia Class of Head Vases (Classical Period). Terracotta kantharos (drinking cup with two vertical handles): heads of a satyr and a woman, ca. 420 BCE. Terracotta, H. 8 1/8 in. (20.5 cm). Fletcher Fund, 1927 (27.122.9) Center: Attributed to the Kekrops Painter (Classical Period). Terracotta bell-krater (bowl for mixing wine and water), ca. 410–400 BCE. Terracotta, H. 8 3/4 in. (22.2 cm). Fletcher Fund, 1956 (56.171.49) Right: Attributed to Polion (Classical Period). Terracotta oinochoe (jug), ca. 420 BCE. Terracotta, H. 9 3/8 in. (23.8 cm). Fletcher Fund, 1956 (56.171.57). All The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

If you enjoy the treasure hunt, you can climb the stairs to the mezzanine and get to the Etruscan collection in Gallery 170. There you will find a beautiful red-figure kantharos (a wine-drinking vessel) that was made in red-figure by the Etruscans of the city of Chiusi, imitating the Athenian technique, and exported from Chiusi to Spina where it was discovered.

Terracotta kantharos (drinking cup), ca. 325–300 BCE. Etruscan. Terracotta, H. 6 1/4 in. (15.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1951 (51.11.10)

Only the big volute-krater from tomb 128 has come on loan from the Archaeological Museum of Ferrara, where the rest of the tomb contents are exhibited. If you want to get an idea about Etruscan crafts, and not only Attic vases, represented in this grave, The Met’s Etruscan collection has many similar (although not identical) artworks that you can admire in Gallery 170. Of note is the splendid pair of bronze handles, each one with two youths holding the bridles of their horses. They were once part of a volute-krater of a type made in the southern-Etruscan city of Vulci and exported in many places such as Spina. Two very similar handles and the foot of a bronze krater were discovered in tomb 128. They are very similar to The Met’s pair; the youths differ by their dress and headdress. Note the winged boots of The Met’s boys, and the raised leg of The Met’s horses in an elegant pose.

Bronze handles from a large volute-krater (vase for mixing wine and water), ca. 500–475 BCE. Etruscan. Bronze, H. 9 in. (22.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fletcher Fund, 1961 (61.11.4a, b)

The youths certainly represent the divine twins Castor and Pollux, called the Dioskouroi (“Boys of Zeus”) in Greek. In Etruria they were called Kastur and Pultuce, the Tinas Cliniiar (“Boys of Tinia,” the Etruscan equivalent of Zeus), and were worshipped as early as the late sixth century BCE. Very popular, they appear in many Etruscan artworks, especially on small bronze sculptures, gems, and mirrors, often with inscriptions of their names.

See more Met objects similar to those found in tomb 128

Left: Bronze candelabrum, ca. 500–475 BCE. Bronze, H. 61 in. (154.9 cm). Rogers Fund, 1961 (61.11.3) Right: Bronze tripod, ca. 525–500 BCE. Bronze, H. as restored 26 in. (66.1 cm). Fletcher Fund, 1960 (60.11.11). Both Etruscan. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Met’s example of a bronze candelabrum, dated to the early fifth century, has statuettes of Herakles and Athena at the top. As for the krater-handles, the bronze tripod is very similar to the one from tomb 128 and both are older than the grave.

Left to Right: Bronze kyathos (ladle), 450–400 BCE. Bronze, H. 3 7/8 in. (9.7 cm). Rogers Fund, 1912 (12.160.4); Bronze kyathos (ladle), 450–400 BCE. Bronze, 3 5/8 in. (9 cm). Rogers Fund, 1912 (12.160.5); Bronze kyathos (single-handled jug), ca. 450–400 BCE. Bronze, 4 1/8 in. (10.5 cm). Rogers Fund, 1913 (13.227.4); Silver kyathos (ladle) with bronze handle, ca. 400 BCE. Bronze, silver, 8 in. (20.2 cm). Rogers Fund, 1912 (12.160.10). All Etruscan. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

These three bronze kyathoi and bronze conical kyathos, used to dip, pour and drink liquids (wine) show today a beautiful green patina. Both types are represented in tomb 128.

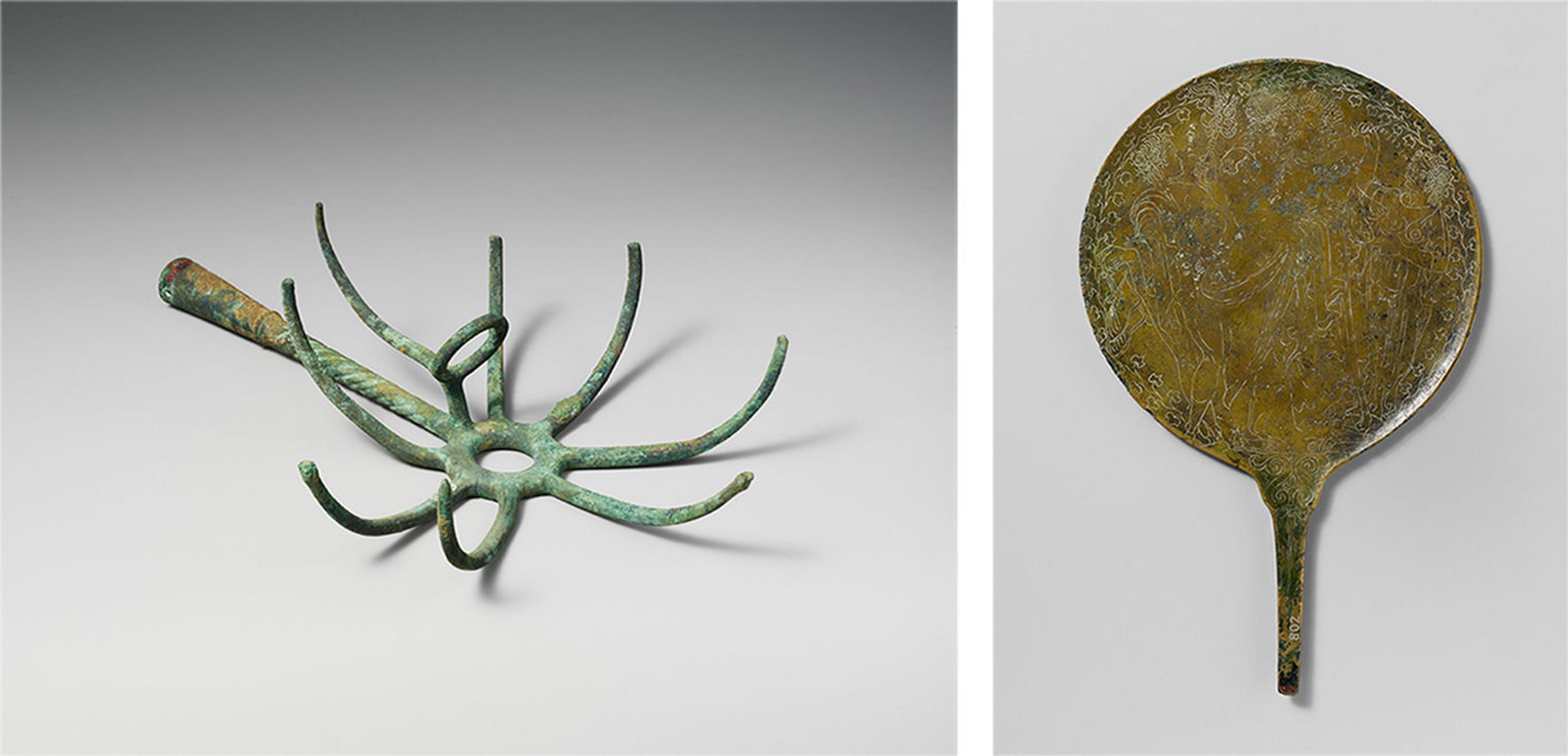

Left: Bronze torch-holder, late 5th century BCE. 10 7/8 in. (27.5 cm). Purchase, 1896 (96.9.375) Right: Bronze mirror, ca. 400–350 BCE. Bronze, H. 10 1/4 in. (25.9 cm) x W. 6 1/2 in. (16.5 cm). Purchase by subscription, 1896 (96.18.15). Both Etruscan. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

This curious object at left is frequent in Etruscan tombs and its function might be elucidated by its depiction in the hands of Admetus on an Etruscan bronze mirror presented nearby: it was a torch-holder.