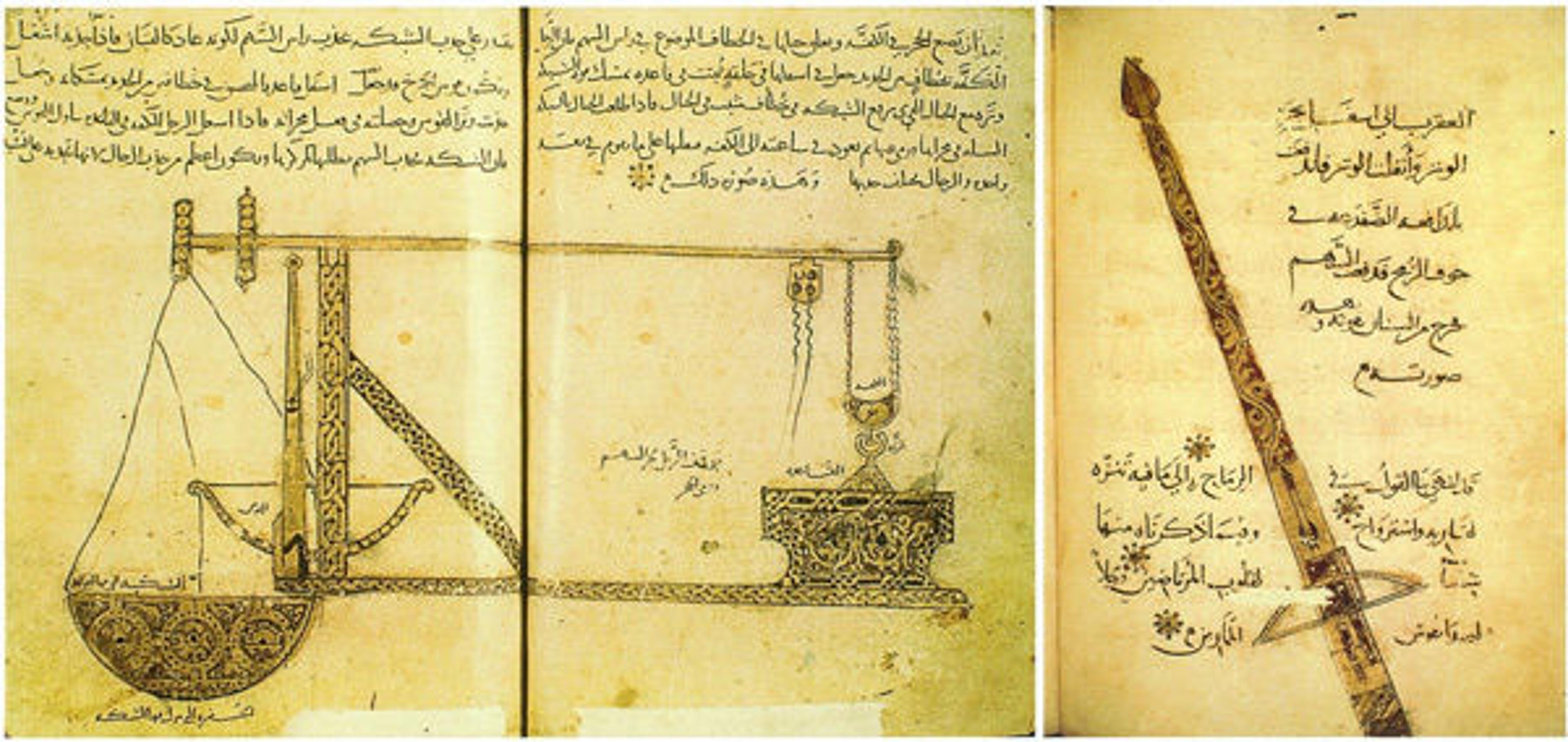

Murda ibn ‘Ali al-Tarsusi. Saladin's Treatise on Armory, second half of the 12th century. Oriental paper, black ink, watercolors and gold; Eastern medieval binding: leather, small hot iron decor and cold; Western dishes Interior (1963); H. 25.5 cm; L. 19.5 cm. Bodleian Library, Oxford, Huntington 264

«In last week's post, my colleague Christina Alphonso shared a tale from her summer travels. My own adventures beyond The Cloisters led in a different direction. The month of July took me to England, where my colleague Melanie Holcomb and I examined works of art that will be featured in the forthcoming exhibition Every People Under Heaven: Jerusalem, 1000–1400 (September 20, 2016–January 8, 2017). »

We saw extraordinary treasures in private collections and in the University of Oxford's Bodleian Libraries. The Bodleian Library first opened its doors to scholars in 1602, its building replacing an earlier, fifteenth-century library! Small wonder, then, that the libraries' holdings are vast in number; the geographic and cultural range of the collections is no less imposing.

Deciding which opening from Murda ibn ‘Ali al-Tarsusi's Saladin's Treatise on Armory to display in our forthcoming exhibition was especially difficult. Two of the better-known illustrations, shown above, celebrate the invention, skill, and surprising beauty of weaponry design. We have chosen an even more interesting opening in the book than these; visitors to the exhibition will be able to see it in September 2016.

After the Bodleian, my adventures took a different turn, as I attended the British Grand Prix at Silverstone. There's nothing more thrilling than Formula One racing. Strange taste in an art historian? Not at all: I see the intersection of genius and artistry in the design and the driving of the cars. At the track, I couldn't help thinking of Saladin's Treatise honoring the razzle dazzle, not of weaponry, but of engineering. These days, nothing beats Formula One cars for those qualities.

Left: Lewis Hamilton crossing the finish line at the British Grand Prix 2015. Image via The Telegraph. Right: Leonardo da Vinci's design for a flying machine. Image via Wikimedia Commons

We can recognize that same kind of genius in the work of Leonardo da Vinci. Try comparing the image of Lewis Hamilton's Mercedes flying across the finish line at Silverstone to Leonardo's drawing of a flying machine. Seems to me that the artist's dream has at last been realized.