Left: Umberto Boccioni (Italian, 1882–1916). Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, 1913, cast 1950. Bronze; 47 3/4 x 35 x 15 3/4 in. (121.3 x 88.9 x 40 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Lydia Winston Malbin, 1989 (1990.38.3). Right: Umberto Boccioni (Italian, 1882–1916). Development of a Bottle in Space, 1913, cast 1950. Bronze; 15 1/2 x 23 3/4 x 15 1/2 in. (39.4 x 60.3 x 39.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Lydia Winston Malbin, 1989 (1990.38.2)

«Today marks the 100th anniversary of the death of Italian Futurist Umberto Boccioni. Known for dynamic sculptures and colorful paintings of modern life in Milan, Boccioni died at just 33 years old, after falling from a horse during cavalry exercises in World War I. Despite his premature demise, he has remained the best-known Futurist artist, and The Met holds the largest collection of his paintings, sculptures, and works on paper outside of Italy. Two such works on view in gallery 908 hold the key to how Boccioni became so well known.»

Boccioni's Unique Forms of Continuity in Space and Development of a Bottle in Space are great examples of the artist's exploration of human movement and the potential energy of an inanimate object. As important works in the history of modern sculpture, they are often included in art books, but visitors might also recognize them from museums closer to home. Similar casts of these works can be found in Italy, Brazil, the United Kingdom, Liechtenstein, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Germany, Israel, Iran, and Japan, and at other institutions in the United States. As a senior research fellow in the Department of Modern and Contemporary Art, I have been taking a closer look at these casts, which are all posthumous, to consider how they made Boccioni famous over the last century.

Left: Fellow Brunella Santarelli taking an X-ray fluorescence reading of Development of a Bottle in Space. Right: Associate Research Scientist Frederico Carò taking an X-ray fluorescence reading of Unique Forms of Continuity in Space. Photos courtesy of the author

The techniques my colleagues at The Met used to help me compare the different versions of the sculptures were appropriately Futurist. The Department of Scientific Research employed X-ray fluorescence to uncover the alloys used in our bronzes and compare them to others, which, in turn, partially explained the different colors of the bronze or brass used. The Department of Imaging used computational photography to produce 3D models of the sculptures so that they could be viewed from different angles on a screen. This allows for precise comparison of the deviations in scale, volume, and surface area between the 3D models, revealing the slight differences in shape and size between them.

Two views of computational photography of Unique Forms in progress. Photos courtesy of Ron Street

While technology tells us that the casts are different, detective work in The Met's libraries and archives tells us why. The story starts in 1912, when Boccioni became, in his own words, "obsessed with sculpture." He wanted to renew the medium by using new subjects and less monumental materials such as plaster and mixed media. The following year he made two plaster sculptures called Development of a Bottle in Space—one white, one red—the first publicly exhibited still-life sculptures.

After Boccioni's death, these works were shown alongside many other sculptures, paintings, and works on paper in a retrospective exhibition in Milan. Until recently, it was thought that the Boccioni sculptures that had not yet been bought, including Development of a Bottle, were destroyed and discarded after that exhibition. Instead they were stored by the sculptor Piero da Verona in his studio in Milan until 1927, when he threw them in a dump!

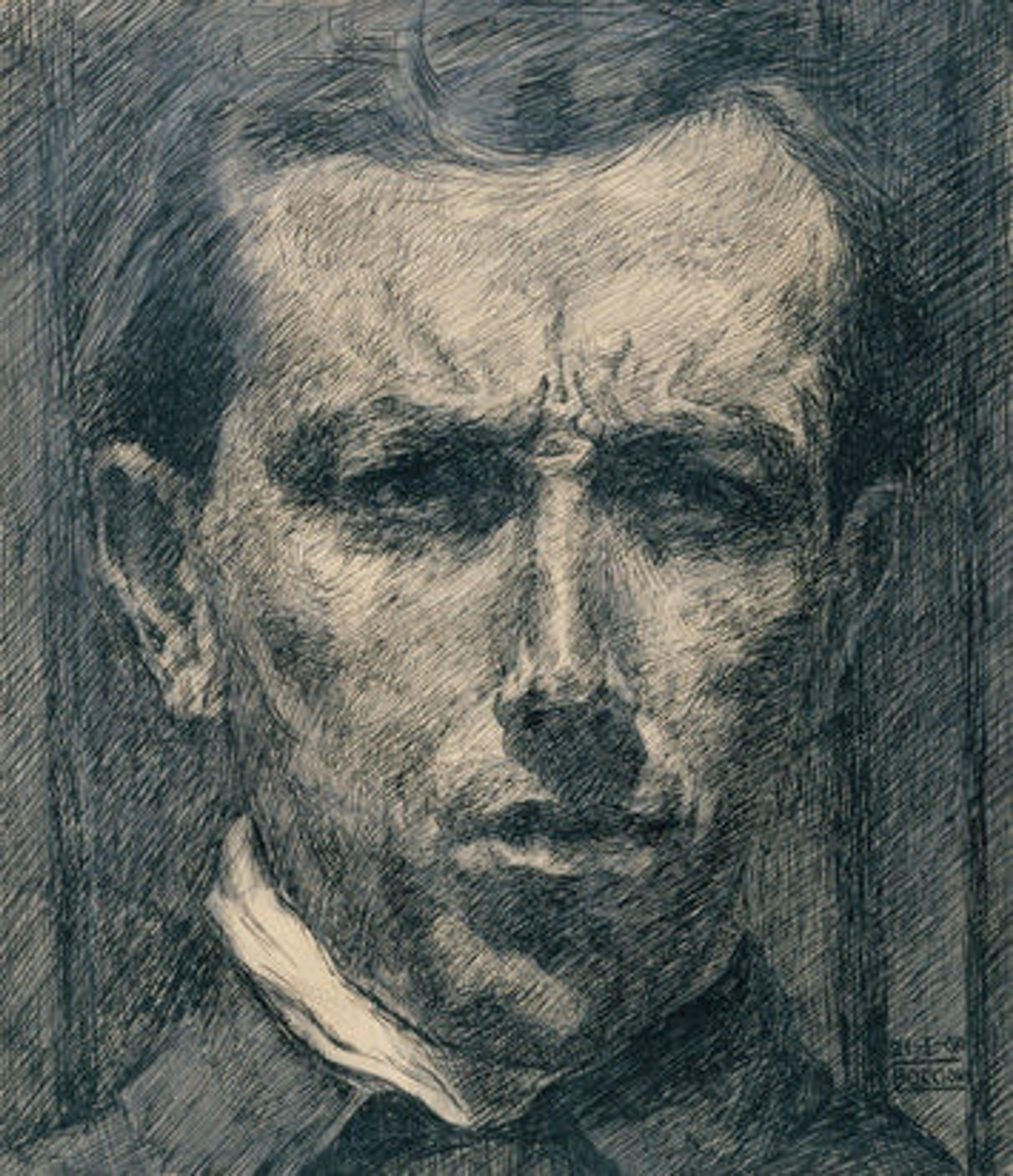

Left: Umberto Boccioni (Italian, 1882–1916). Self-Portrait, 1910. Ink, wash and graphite on paper; 10 1/4 x 8 3/4 in. (26 x 22.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Lydia Winston Malbin, 1989 (1990.38.12)

So how did Boccioni sculptures go from unique plasters in a dump to numerous bronzes in museums? Unique Forms survived because it was in a private collection, and Marco Bisi, a young relative of Boccioni, managed to find and repair the red plaster fragments of Development of a Bottle from the dump. (Both of these plasters are now in the Museu de Arte Contemporânea at the University of São Paulo.) Then, in the 1930s, the leader of the Futurist movement, F.T. Marinetti, began making casts of the two works. Even though Boccioni himself had argued against the use of bronze in sculpture, Marinetti wanted to preserve the artist's legacy in a more robust material. These reproductions played an essential role in reviving interest in the artist, but also resulted in there being a variety of versions.

Following the Boccioni retrospective in Milan's Castello Sforzesco in 1933 and the seminal exhibition Cubism and Abstract Art at the Museum of Modern Art in 1936, the smooth brass casts from the 1930s were bought by the Galleria d'Arte Moderna in Milan and MoMA. In 1950, Benedetta Marinetti (F.T.'s widow) made two new bronze casts of each sculpture, this time including the original base from the plaster sculpture and a rougher surface. One pair stayed in Europe, and the other was bought by Harry and Lydia Winston, Futurist art collectors living just outside Detroit, who donated a large part of their collection to The Met in 1989. The Winstons, like other owners of Boccioni casts, exhibited their collection regularly around the United States and overseas.

Unlike the fragile plaster originals, which were bought by the Brazilian collector Francisco Matarazzo Sobrinho in 1952, the bronze and brass versions could travel and became increasingly famous. Demand for new casts of Unique Forms grew among museums and private collectors, and bronzes were made for museums from the plaster, again with a slightly different base, in 1960 and 1972. Also in 1972, La Medusa, a commercial art gallery in Rome, made an edition of 10 surmoulages, or casts made from a bronze rather than a plaster. At first, some museums did not want to buy the slightly smaller and less defined surmoulages, but today more than half are found in museums. All of the earlier casts can also be found in museums.

A view of Unique Forms of Continuity in Space and Development of a Bottle in Space in gallery 908

The story doesn't end there: Unique Forms has appeared on the Italian 20-cent euro coin since 2002, and numerous contemporary artists like Rashid Rana have been inspired by Boccioni's sculptures. Even if Boccioni might never have chosen to cast his works in bronze, casts like those in gallery 908 are the reason why so many know his work and why this centenary is an important date in art history.