Betsabeé Romero’s sculptures play with the meanings of materials, resignifying the form and function of everyday objects, particularly parts of cars and other vehicles. By carving symbolic designs into recycled tires, she creates artworks that reference ancient motifs and evoke reflections on movement.

Havana residents imprinting tire motifs on their clothing as part of Betsabeé Romero's Ciudades que se van (Moving Cities) (2004)

At the 2004 Havana Biennial, her work titled Ciudades que se van (Moving Cities) took inspiration from the city’s historic architecture. Romero engraved architectural motifs on tires and then invited the public to use them to imprint the patterns on their garments and other textiles, creating an interactive, recursive engagement with local residents.

In the spring of 2024, Romero installed large tractor tires engraved with pre-Hispanic iconography a few blocks from The Met on Manhattan’s Park Avenue. Conceived of as a dialogue with The Met’s collection of ancient American art and the artistic heritage of a growing percentage of New York City’s residents, the project serves to heighten the visibility of migrant workers in the United States.

Memory is more important than speed.

“Tires in general have been a driver of modernity, an important symbol of speed, and a problem that has also done us great harm, losing their tread, leaving no tracks, effacing, leaving behind, running over. My tires go in reverse, they rotate to recover the memory of what has been trapped, what has been effaced, what has been neglected and left behind,” says the Mexico City–based artist.

Romero recently spoke with Laura Filloy Nadal, curator of the Arts of the Ancient Americas at The Met, about migration, cultural identity, and memory. Their conversation has been edited and condensed for publication.

Two images of Betsabeé Romero’s 2024 installation Traces in Order to Remember. Left: Warriors in Captivity (2007). Right: Rubber and Feathered Snakes (2023)

Laura Filloy Nadal:

You have always liked to experiment with materials that may be conventional in certain contexts but unusual for making art. For example, you have worked with thread, plastic, chewing gum, and rubber. They are all substances present in our everyday lives. What do you like about these types of materials?

Betsabeé Romero:

The theme of mobility has led me to objects like the tire, which is made of rubber, and rubber has a history involving slavery and colonialism in Africa and the Americas, which is very long and deep and forms a circle that is quite atavistic.

Rubber led me to a sort of reverse movement. And I realized that the tire can move, but not on its own. When it does move, it leaves a track. When I decided to start working with tires, I began with the material of rubber itself, its history, and the tread as a kind of stamp or seal. Ultimately, I recycle tires not only because they are a complicated type of refuse in this world in terms of the speed and the amounts in which tires are produced and used daily, but also because I could resignify the tire as a cylinder seal.

All this research and work made me realize how cylinder seals were instruments of engraving, memory, and the impression of elements from cultures which have left a trace. These seals have been found to exist in all cultures. They are far more universal than tires and have given me a romantic argument that memory is more important than speed.

Top left: Roller stamp with birds, 10th–15th century. Mexico, Mesoamerica. Ceramic, W. 1 3/4 × D. 2 3/8 in. (4.5 × 6.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Museum Purchase, 1900 (00.5.1156). Top right: Stamp, Butterfly, 14th–early 16th century. Mexico, Mesoamerican. Mexica (Aztec). Ceramic, W. 1 1/2 in. × D. 1 in. (3.8 × 2.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Museum Purchase, 1900 (00.5.1169). Bottom: Figure Vessel, 8th–12th century. Ecuador. Manteño. Ceramic, pigment, H. 3 3/8 × W. 4 × D. 8 1/4 in. (8.6 × 10.2 × 21 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Peggy and Tessim Zorach, 1988 (1988.117.10)

Filloy Nadal:

Yes, these seals roll, leave marks, and are also similar to the pintaderas—ceramic, mud, or wood stamps from the pre-Hispanic period—that have been found throughout the Americas, in Mesoamerica as well as South America. They were used to apply motifs on ceramics and leave their impressions on a range of materials, including textiles, and even the body. Your work focuses on the transformed tire, but you also utilize that same sense of leaving an impression on other materials.

Romero:

I was interested in reinscribing manually, slowly, artisanally, the iconography of cultures that have been left behind, but also in printing on materials that are not conventional in contemporary art. When I was working with some Taíno seals, I engraved on fondant or sugar glaze. On another occasion, I engraved on wire mesh to remember this idea of a cage in which cultures historically have been kept.

In different arenas, I have employed various symbolic materials that were used in the past. But what has interested me most in what I have studied about these seals is the realization that everything means something—the material, the shape, the size, and the color all have meaning.

Betsabeé Romero's Ciudades que se van (Moving Cities) (2004) where the artist engraved and painted tires that left imprints on the roads of Havana

Filloy Nadal:

The 2004 Havana Biennial was one of the first times you explored this way of rethinking textiles, rethinking seals, rethinking these materials that rotate, and you spoke about these cylinder seals that move and leave an impression, a trace, a memory.

Romero:

Nearly all these cylinder seals could leave a mark on ceramics, on the body, and on architecture, so I wanted to use these tires, as if they could be put back on one of these cars that are so symbolic of Old Havana.

In a typical Old Havana neighborhood, I looked for architectural flourishes characteristic of the decaying buildings there—some part Mudéjar, others more Art Deco—and engraved these flourishes on the tires, which are called gomas there.

I used these engraved “retreads” to print tracks on the street. The piece was called Ciudades que se van (Moving Cities) and spoke about how cities live where people culturally practice their traditions, and about the ways that culture has permeated the body, mind, and soul. Cities live where people sing, where they cook, where they sew, where they act like the cultural human beings that we are. The spirit of Havana and Cuba is in many other places. But in this case, after I had printed the tracks on the pavement, I took the seals, the engraved tires, to the neighborhoods where the architectural flourishes came from to do a workshop with the people living there. We used the seals to print on their household textiles, towels, dishcloths, and handkerchiefs. People started to get excited and got out their team jerseys and other clothing. This experience left another trace where the iconography I engraved on the tires had emerged.

Betsabeé Romero’s Tejedores de lazos de México para el Mundo (Weavers of ties from Mexico to the world) (2020)

Filloy Nadal:

We’ve talked previously about how architectural motifs that reproduce weaving patterns have been used since very early times and this reminded me of the work you presented for the Mexican Pavilion at Expo 2020 Dubai, where you employed another unusual contemporary material, recycled synthetic raffia, for weaving.

You used this material to produce more than 700 square meters of fabric, handwoven by women from Etzatlán, Jalisco, to create an enormous textile to envelop the entire pavilion building, which is really quite impressive.

Romero:

I was invited to do the pavilion, but there were few resources and no time. The building was very large, and the architecture was already complete. It would have to be something external, and I remembered this tradition of covering buildings and began thinking about ribbon-like bands and about understanding ties to the world of women’s hands.

I started looking into having something woven very quickly and realized that it would have to be a community. The community I found did not have a centuries-old tradition of weaving as in Chiapas, Oaxaca, or Yucatán, but rather consisted of female weavers who specifically came together as a family in mourning to weave for religious celebrations. They wove obsessively during the pandemic, and this manner of washing away their sorrows and accompanying each other in collective grief multiplied. Bringing together this type of work with art has always interested me. Art can help overcome the collective grief that is deep and very common in our countries.

Top Left: Betsabeé Romero's Réquiem por los desaparecidos (Requiem for the Missing) (2007). Image courtesy of the artist. Top Right: Betsabeé Romero's Petate Car (2001). Bottom Left: Detail depicting a funerary bundle, mid-sixteenth century. Folio 68r from a facsimile of Codex Magliabechiano. Image courtesy of the Internet Archive. Bottom Right: Detail of two porters carrying petates on foot, 1577. Folio 316r from an illustrated manuscript of General History of the Things of New Spain by Fray Bernardino de Sahagún: The Florentine Codex. Book IX: The Merchants, by Fray Bernardino de Sahagún (1499–1590). Image courtesy of World Digital Library

Filloy Nadal:

This reminds me of something else that I have always found fascinating about your work, which is this recovery of the idea of the petate, the mat where flat structures cross and intertwine, which you use to wrap architecture, but in pre-Hispanic times they were used to wrap the body and precious materials such as feathers, and to carry luxury goods by foot from distant regions.

Romero:

Petates interest me knowing that they were part of the mortuary ritual for wrapping bodies. The act of wrapping—whether a body or a building—is quasi-protective and something that seems a bit maternal, and always involves fabric, which I have used on cars as well.

In Mexico, about a half a million cars are always parked and do not move, because they become family symbols. When someone dies, the family cannot get rid of the car because it is like part of the father or grandfather. In front of my home, a car that I have photographed was just sold after sitting motionless for the thirty years that I have lived there. The owner died about fifteen years ago, but the car hadn’t moved for fifteen years because it was in disrepair. All these mortuary rituals, in terms of collective mourning and the contemporary altars of the dead, this question of how things die or not, and the symbol of wrapping, and with a petate, have been very useful to me.

Left: Betsabeé Romero’s The Endless Spiral (2024). Right: Feathered Serpent Pendant, 1325-1521. Mexica (Aztec). Shell, H. 1 5/8 × W. 1 7/8 × D. 1/4 in. (4.1 × 4.8 × 0.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of the Mol Collection, 2020 (2020.386.1)

Filloy Nadal:

You inaugurated a new work called La espiral sin fin (The Endless Spiral) at the Venice Biennale, a work which incorporates pre-Hispanic motifs, but above all contemporary artisanal referents that have had a tradition among Mexican artisans.

Romero:

Featherwork is something that has always fascinated me, and a challenge I always face is that the things that I install should not be heavy. I remember the first time I did a large installation. It was in an enormous cathedral-like temple in Lille, France, in which they let me intervene, but only if the entire installation did not exceed five kilos, so I made it using feathers as metaphors. It was a coronation, instead of an ascension, it was a descent from a coronation back to earth. The coronation of the Virgin became a series of feather headdresses descending to a place where visitors can slip into one and be crowned.

I am still using that metaphor now in Venice. For The Endless Spiral, the idea is that these feathers have flown but continue to tread on the earth as well. Because deities, at least the ones I know, always have these two aspects; for example, the great Quetzalcoatl is both feathers and serpent. They fly, but they are also connected to the land. They never leave the ground. And when considering Western authorities with all their individualism, the first thing that comes to mind is that people are no longer grounded. In contrast to the apparel of Western power, I have often used these feathers to make round, horizontal, collective headdresses, connected to the earth and to the forces of nature.

Two images of Betsabeé Romero’s 2024 installation Traces in Order to Remember. Left: Rubber and Feathered Snakes (2023). Right: Close-up of Warriors in Captivity (2007)

Filloy Nadal:

Just a few blocks away from us here at The Met, you have works on exhibition on Park Avenue. There are tires of various types in different sizes, and to me, the tires represent the experience of migrants. These objects carry the symbolism of movement. Migration leaves traces on a path and these paths wear away at the border over time. By engraving the tires with iconography, you’re making permanent the tread that is erased in this process of migration.

Romero:

Yes, it’s called Traces in Order to Remember (Huellas para recordar), and it’s dedicated to all migrants who seem anonymous, timeless, to not have or be part of a great history or culture, who have oftentimes been erased, neglected, and run over by laws and governments, by many things on both sides, on many sides. And I want to do just the opposite: to make visible and dignify the culture they are part of, and have been for many generations, as well as the mark they have left.

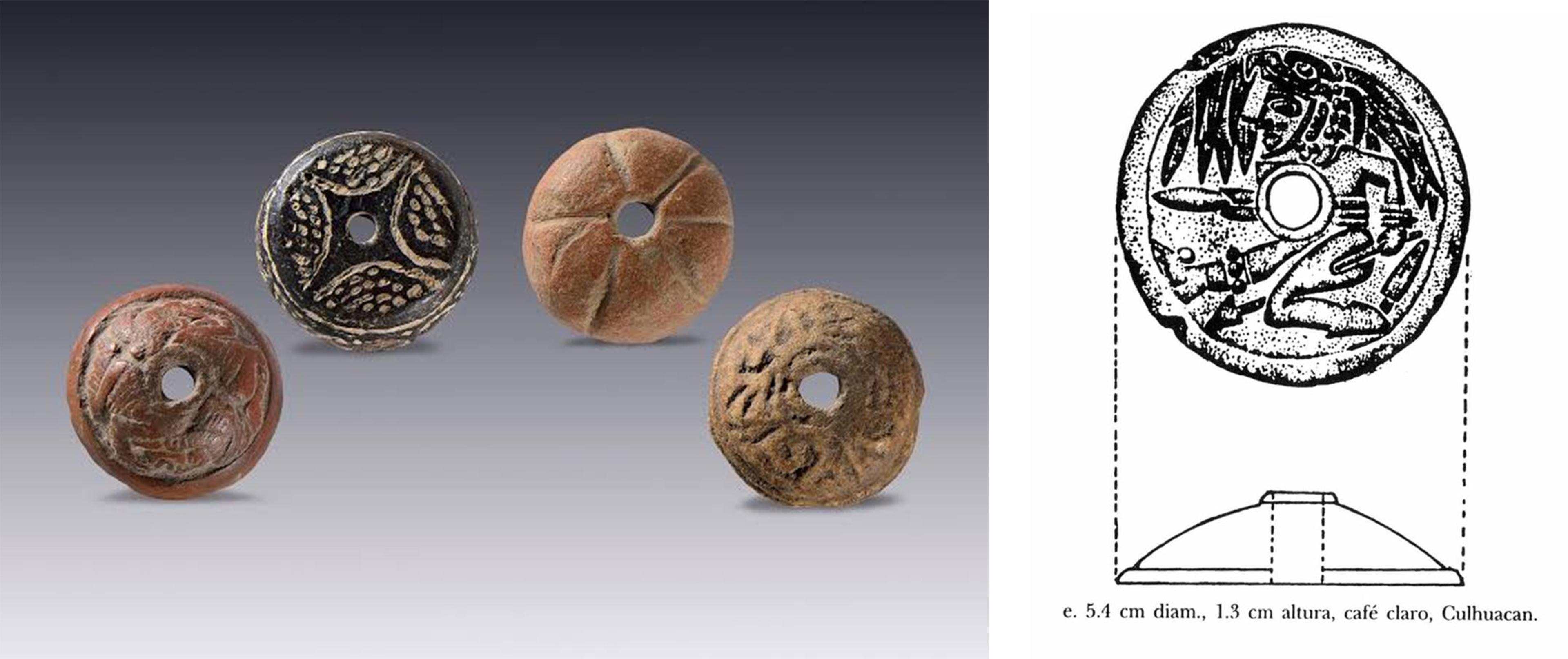

Top Left: Spindles with diverse designs. Modeled clay with incisions. Image courtesy of Museo Amparo. Top Right: Hasso van Winning, "Malacates prehispánicos con figuras humanas en relieve," Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas 16, no. 64 (1993): fig. 5e. Bottom Left: Betsabeé Romero engraving a warrior figure for Warriors in Capitivity III in 2023. Image courtesy of the artist. Bottom Right: Warriors in Captivity III (2023) from Romero’s 2024 installation Traces in Order to Remember

Filloy Nadal:

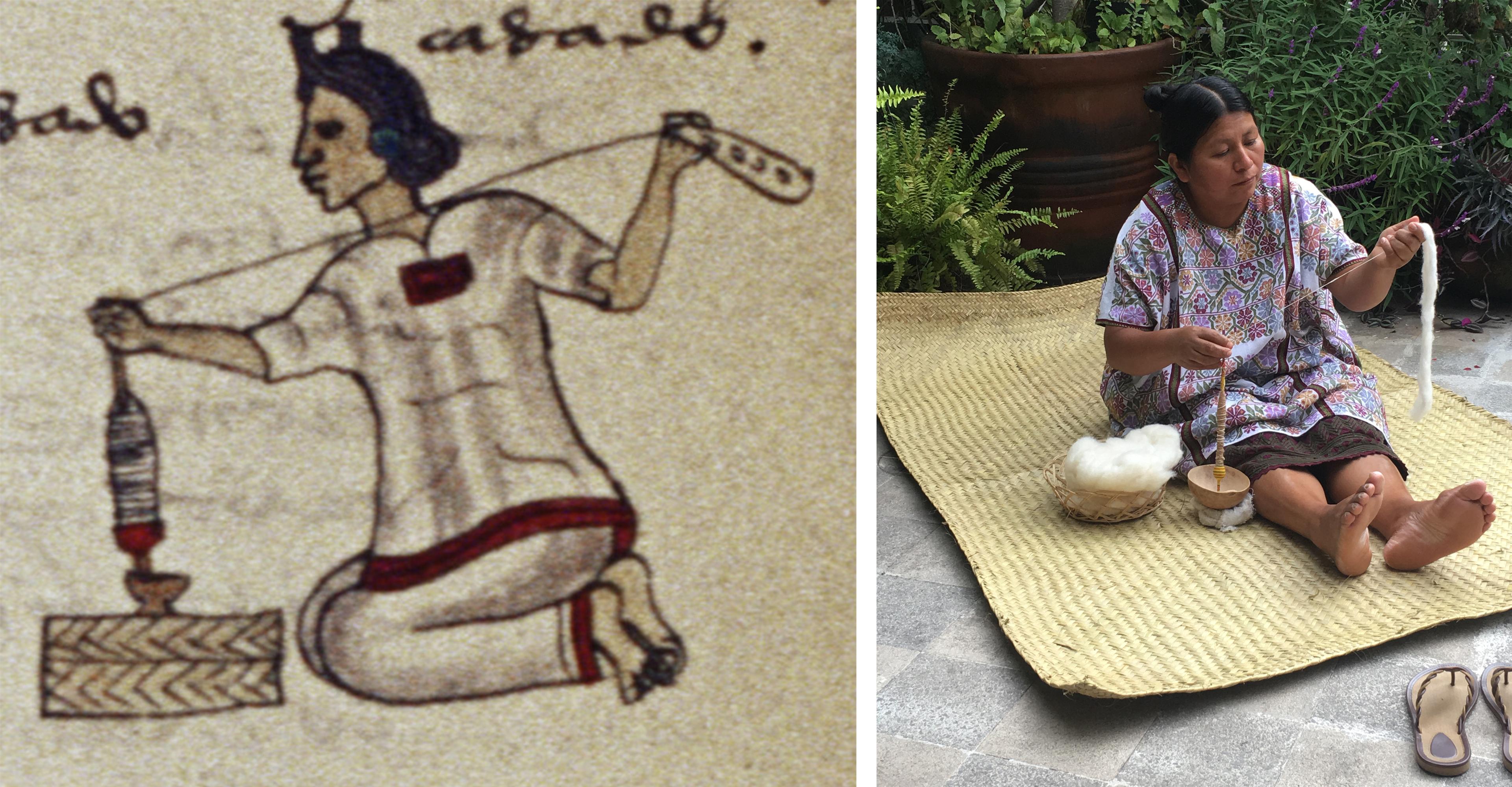

Your work takes pre-Hispanic imagery from objects like spindle whorls, traditionally used to spin textile threads, as a source of inspiration for the engravings on these tires. But then you also reinterpret them and seek to extend that meaning and bring it into the modern era. The engraving you’ve incorporated onto the tires in the Park Avenue installation are drawn not only from the imagery on the spindle whorls themselves, but also from the traditional textile patterns woven from these spun threads.

Romero:

Yes, and some of the malacate spindles are engraved with characters or geometric figures. I became interested in figures like the warriors and ball players I found on pintaderas, whose motifs are nearly always more abstract and geometric. These warriors or players spin and dance as they are used. They grow fatter like pregnant women as more thread is made. The movement of the warriors and players weave that memory, their life weaves a story.

Some of the seals I’ve chosen have iconographic elements of embroidery or indigenous ceramics still found today but have been common and preserved for centuries throughout Mesoamerica. And I believe that these traces can cross borders, remain, and continue for generations with this installation and throughout the lives of these migrants.

Left: Detail of a Mexica (Aztec) woman spinning cotton, ca. 1541. Folio 68r from Codex Mendoza. Image courtesy of Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford. Right: Victorina López Hilario in Mexico City, 2018. Photo by Laura Filloy Nadal

Two images of Betsabeé Romero’s 2024 installation Traces in Order to Remember. Left: On the Other Side of the Track (2017). Right: Moon Seal (2010)

It is a great honor, on the one hand, to have my works on Park Avenue, such a busy and important avenue, because it is a public space. And being open to the public means that what you do also has to be easily accessible in terms of meaning. This is why I think it is important to have tractor tires that have to do with working the land, like many day laborers who have crossed the border to do so in this country, as well as tires from trucks and other transportation, in which many migrants cross legally or illegally. All of this relates to mobility and to the migrants seeing how, with gold leaf to contrast the trash, all this iconography from these cultures of which they are a part is engraved.

Art can help overcome the collective grief.

I have always been very interested in history and the plastic arts and in recovering the value of pre-Hispanic cultures not only historically but also aesthetically because they have created great masterpieces of enormous beauty and unquestionable significance. But this is not very well known in Mexico itself. You can go through formal schooling up to the university level and never study pre-Hispanic art in many programs or career tracks. And that is why it is a responsibility of contemporary art, at least for me, to work to preserve that memory.

Artist Biography

Betsabeé Romero was born in 1963 in Mexico City, where she lives and works today. In 1984, she earned her BA at the Universidad Iberoamericana, quickly followed by an MFA at the Academia de San Carlos in 1986. Romero went on to study at the Louvre and the Beaux-Arts de Paris, before returning to Mexico and earning an MA in Art History from the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México in 1994. As an internationally acclaimed visual artist, she has showcased her works throughout the world, including exhibitions at the Havana Biennial, the World Expo in Dubai, and more recently, her installation on Park Avenue, New York.