When The Met closed its doors in March of this year, it began a new, uncertain chapter in the institution's 150-year history. We invited staff from across the Museum to send us dispatches from wherever they may be, about the innovative ways they were able to adapt, create, and care for the collection and each other as the world was struck by new and dangerous circumstances. This is the final installment of a four-part series.

—The Editorial Team

'Months of work would have been lost': Eric Breitung, Research Scientist

Breitung processes accelerated aging tests in The Met's Department of Scientific Research, that were put on hold for months during museum closure. Images courtesy of Eric Breitung

As one of the few scientists who were occasionally allowed into the building during closure, I went on-site to wrap up experiments that started before the shutdown and to stave off equipment failure after power outages. The building was eerily empty, aside from the occasional cockroach finding its way through the building's dry plumbing pipes! Even dozens of accelerated aging tests I removed from the ovens sat on hold to save months of pre-shutdown work.

The hardest part of closure has been our inability to start new experiments. However, the shutdown has given me the time to work through much of the data I collected over the past year with our department's array of analytical equipment. It’s tough to address data gaps without being able to use the equipment. But as access to the labs has become more frequent, I’ve had just enough time to put fresh samples into the machines. And now, after installing a webcam in the lab, I can run the samples from my computer at home.

Scientific equipment captured on the laboratory's newly installed webcam. Image courtesy of Eric Breitung

'We were able to provide a glimpse': Melissa Bell, Producer and Editor, Digital Content

Instead of filming in the Museum's galleries or on a set, producer Melissa Bell had to oversee shoots from her bedroom. Image courtesy of Melissa Bell

One focus of my job as a producer in The Met's Digital Department is to create special, exhibition-related interpretive digital content that prepares and enhances visitor experience before, during, and after their trip to The Met. But when the museum closed due to COVID-19, patrons were unable to visit three wonderful exhibitions that had only recently opened—Sahel: Art and Empires on the Shores of the Sahara, Photography’s Last Century: The Collection of Ann Tenenbaum and Thomas Lee, and Gerhard Richter: Painting After All—in person.

Sadly, the Richter exhibition was only on view for 9 days before the closure. It was devastating to everyone who worked on the show. With little time or access to our normal resources, we had to shift gears and come up with ways to bring the exhibitions to people at home. We created "virtual tour" videos, utilizing the beautiful installation photography previously taken by The Met’s Imaging Department—as well as high-resolution photos of the artwork—to guide our audiences at home on a simulated walk through the shows. For Photography’s Last Century, we remotely assisted photographs curator Jeff Rosenheim as he recorded himself discussing a selection of works in the exhibition. For both the Sahel and Richter exhibitions, we brought some of the beautiful interpretive media online that were only visible in the galleries, such as the immersive feature-length documentary Gerhard Richter Painting and excerpts from the beautiful film Living Memory: Six Sketches of Mali Today. While videos can't replace the experience of seeing art in person, we hope that we were able to provide a glimpse of that magical experience to our audiences exploring at home.

Stills from interpretive media created to accompany exhibitions that were no longer physically accessible to the public.

'We very quickly pivoted': Tony White, former Florence and Herbert Irving Associate Chief Librarian

Collection monitors begin their day by feeding the koi in the Astor Chinese Garden Court. They are wearing khaki face masks produced by volunteers in collaboration with The Met's Department of Textile Conservation. Image courtesy of Tony White

I supervise staff who are responsible for a wide array of tasks, as well as librarians in the Nolen Library, the Irene Lewisohn Costume Reference Library, and the Cloisters Library and Archives. When we initially left the museum in mid-March, we all thought we’d be back in the office in a couple of weeks. As the work-from-home experience stretched from March to April, we all entered a period of tremendous anxiety and gloom, worrying constantly about pending head-count reductions. This was compounded by a spike in NYC's COVID-19 cases, Governor Cuomo’s daily briefings, and a crescendo of "Zoom fatigue."

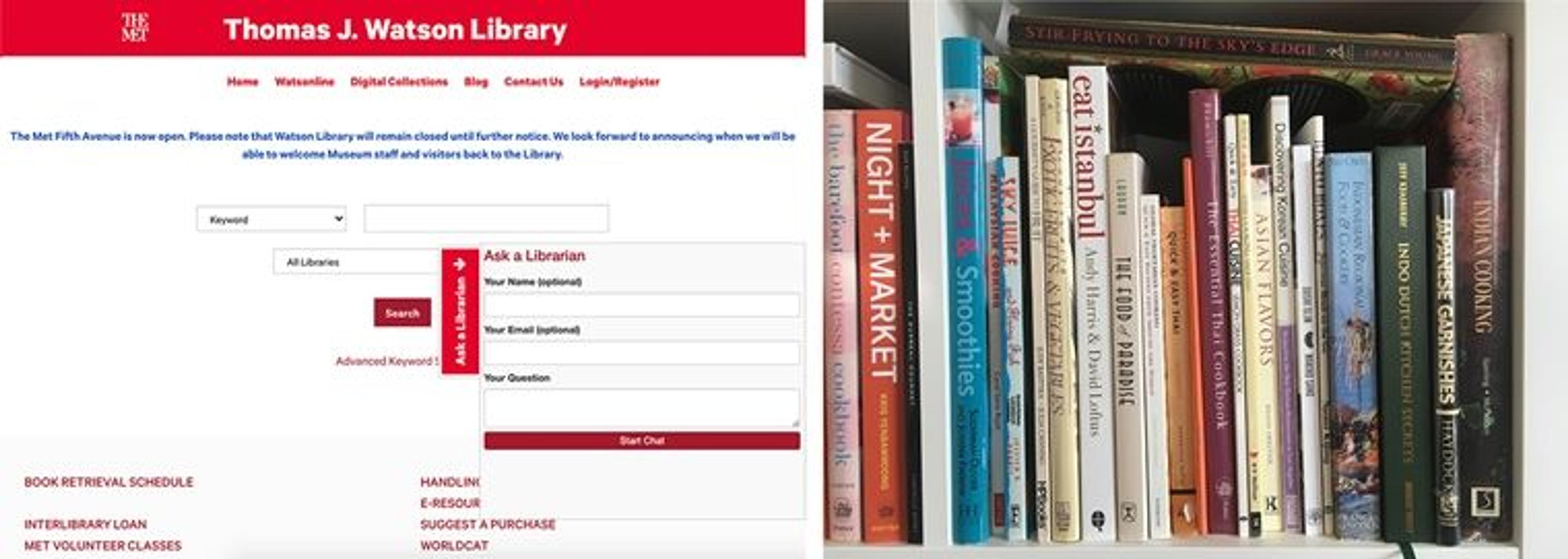

When the museum closed down, our immediate need to maintain was to ensure that all library staff had access to the technical support necessary to allow them to work at from home. At the Watson Library, we very quickly pivoted from our in-person reference desk service to a virtual chat reference service, which we launched on March 30th. We began offering programming for the library's Friends Group, and for fun I gave a presentation in April that profiled useful books and recipes from my contemporary cookbook collection.

I also participated on the collections monitoring teams, coming in monthly to check on museum and library collections. Each shift started by feeding the koi fish in the Astor Chinese Garden Court, followed by a walk through selected galleries with flashlights in hand, looking for anything that seemed unusual. The Met is a place and a space for inspiration in the company of thousands of other visitors; the uplift we felt in accepting this responsibility was a much-needed balance against the empty hush of darkened galleries and the absent energy from thousands of daily visitors.

Left: A new virtual chat service was added to the Watson Library's website when in-person reference became impossible. Right: A small selection from White's personal cookbook collection, which he presented to library friends. Image courtesy of Tony White

'A sense of joyful relief': Amanda Lister, Chair of the Volunteer Organization

Members of The Met's Volunteer Organization connect with Met staff over the virtual meeting software Zoom. Image courtesy of Amanda Lister

The Volunteer Organization includes 1,200 active volunteers who staff information desks and member lounges, give tours to adult and school groups, work in the libraries, survey visitors, help with education programs and assist in other departments. After the Museum closed, we quickly realized there were some things we couldn't do without visitors in the building and tried our best to focus on the work we could get done off-site. With the support of our liaisons in the Education Department and approximately fifteen curators from across the institution, training for our volunteer guides continued online. We even ran into an unexpected positive: expanded virtual capacity allowed us to open the training sessions to a larger number of attendees and, by recording them, make a video archive. We found that we were able to make training and enrichment open to all, including volunteers who are busy with other jobs during the week.

The precursor to virtual training was enhancing our technology skills. With some trepidation, we—just as in organizations all across the world—introduced the volunteers to a virtual meeting platform. We weren’t sure that all of our volunteers would have the devices, connectivity and comfort to make the shift. We developed primers and hosted practice sessions. We learned how to use the software program Otter to provide captions to those who need them.

Success came sooner than we expected. After just the first couple of weeks of isolation, the ability to see friends and colleagues again brought a sense of joyful relief. Groups began to host book clubs, art study groups, and forums for sharing the best of what to read, watch and hear. The platform enabled us to continue team and management meetings virtually and meetings with Met staff, with whom we work so closely. As it has for more than 50 years, the Volunteer Organization rose to the challenge of adapting to keep connected to The Met . . . and to one another.