When the British artist Frederic Leighton exhibited his iconic painting Flaming June in 1895 at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, critics assessed it as one of his finest submissions, and it quickly became a popular hit. Now, almost 130 years later, it continues to draw praise and attention as the subject of recent pieces in the Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal, Airmail, and NBC New York. The current installation at The Met, on loan from the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico through January 2024 due to the closure of its galleries from devastating earthquakes in 2020, represents an astonishing comeback for the painting, which was eclipsed for most of the twentieth century as other artistic styles dominated. Why are we so fascinated by Flaming June? Taking a closer look at this picture and its history can help us understand the work’s magnetism.

Leighton was one of the most celebrated British painters of his generation. A proud traditionalist but also spirited and independent-minded, he championed time-honored ideals of beauty and refinement with dramatic flair. The artist’s style was well suited to the tastes of the British cultural elite; in 1878, when Leighton was still in his forties, he became President of the Royal Academy of Arts, Britain’s premier art institution. Famously urbane and accomplished, he was admired and envied by his compatriots, who nicknamed him “Jupiter Olympus,” reflecting his towering status in the art world and his passion for Greek and Roman antiquity.

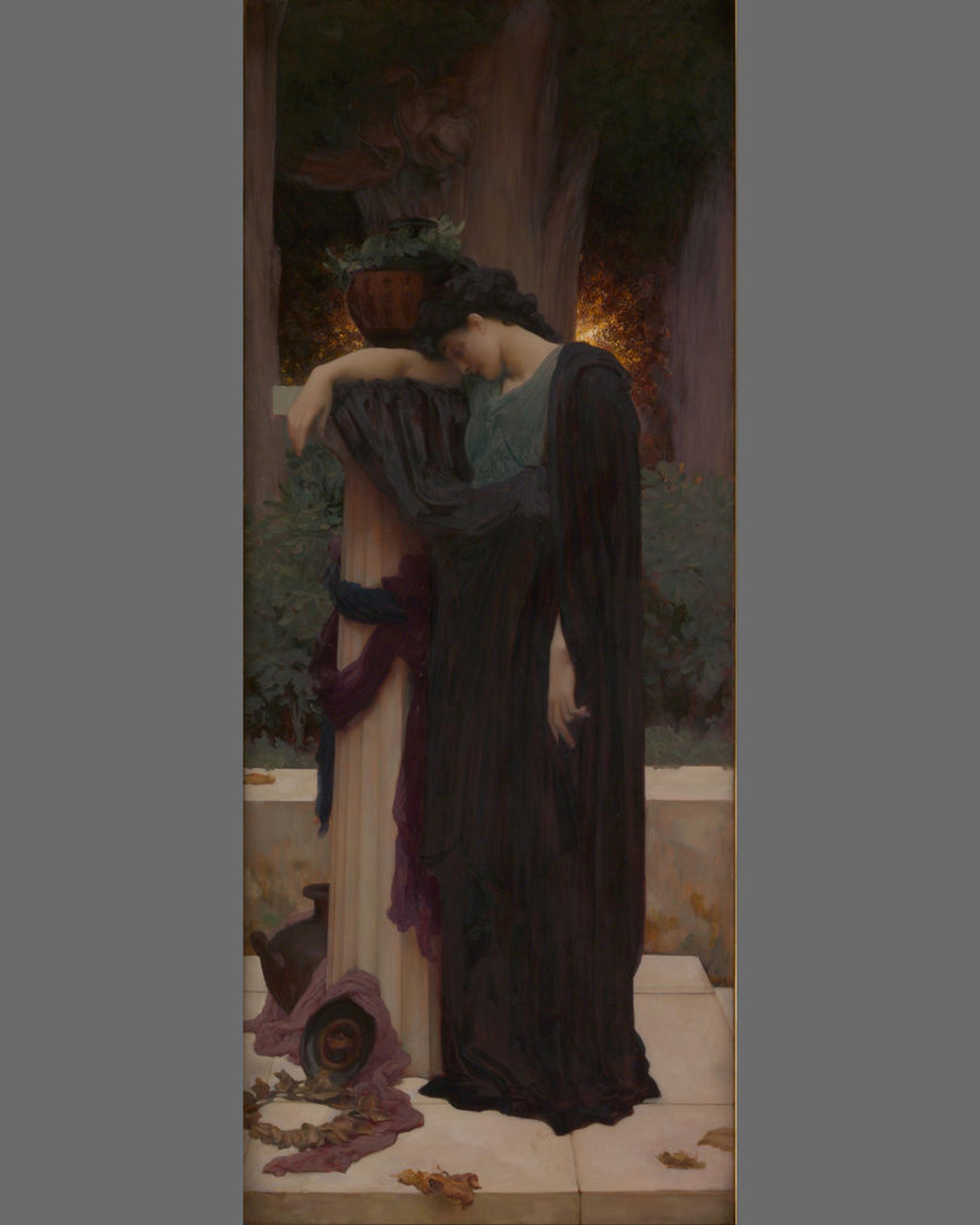

Frederic, Lord Leighton (British, 1830–96). Lachrymae, 1894–95. Oil on canvas, 62 x 24 3/4 in. (157.5 x 62.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Catharine Lorillard Wolfe Collection, Wolfe Fund, 1896 (96.28)

By the 1890s, Leighton had a considerable reputation to uphold and a proven strategy for creating acclaimed works. He specialized in depictions of women in allegorical or mythological guises, their erotic appeal disciplined by elegant grandeur. These subjects provided a point of departure for the display of Leighton’s talent for gorgeous color, complex poses, and swirling drapery. In Flaming June, he executed the components of his strategy to perfection.

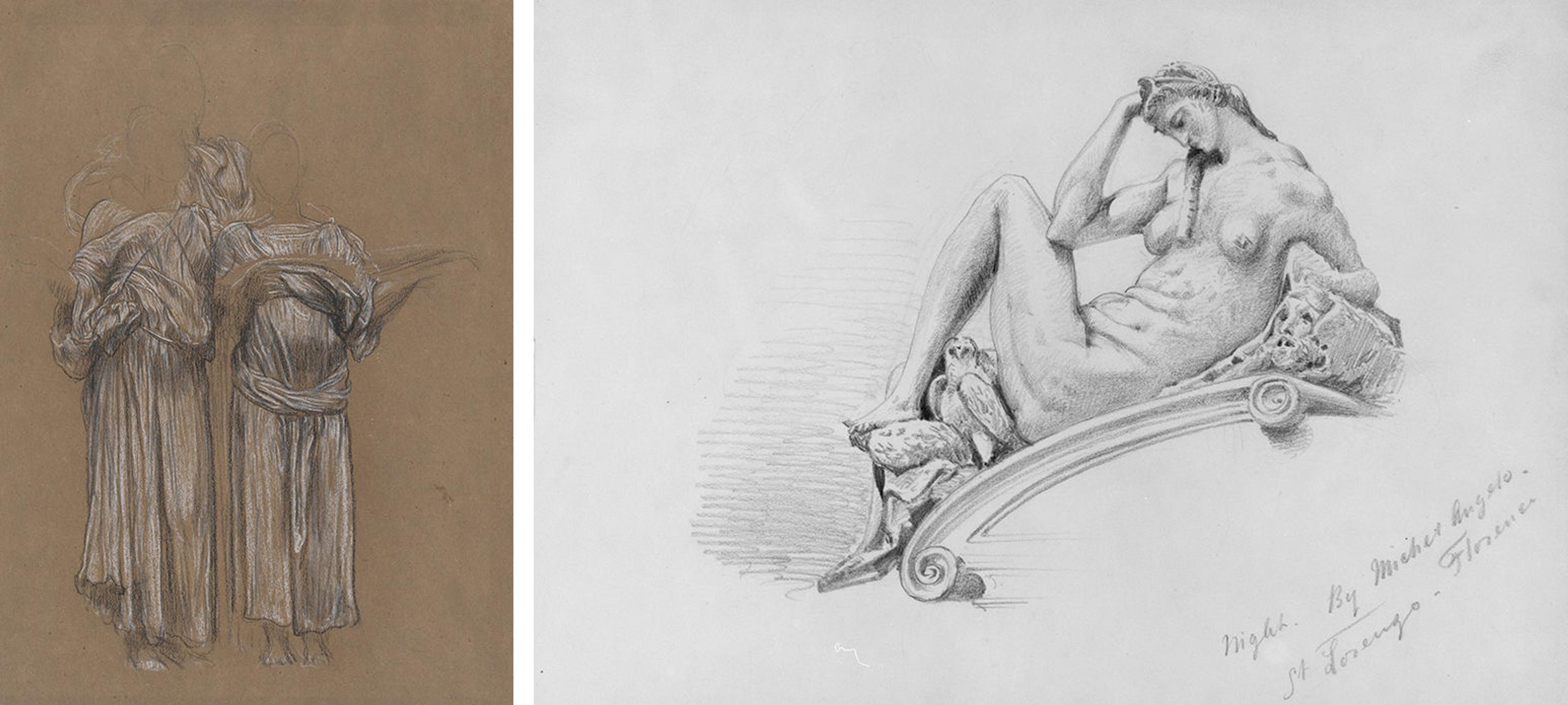

Frederic, Lord Leighton (British, 1830–96). Study of Three Standing Draped Female Figures for “Music,” ca. 1883–85. Black and white chalk on brown paper, 15 1/4 in. × 11 in. (38.7 × 28 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, PECO Foundation Gift, 2016 (2016.62). Right: John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925) after Michelangelo Buonarroti (Italian, Caprese 1475–1564 Rome). Night, 1870. Graphite on off-white wove paper, 10 3/4 x 15 1/4 in. (27.3 x 38.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Francis Ormond, 1950 (50.130.143z)

The painting's subject is straightforward: a sleeping woman. Leighton channeled the motif’s long history—specifically, Michelangelo’s sculpture Night—and its associations with beauty, sensuality, tranquility, and vulnerability. Even without knowing the painting’s title, we can guess the season. The sun blazes on the water, and peeking over the wall is oleander, which blooms most profusely in May and June. Despite the shade provided by the golden awning, the woman's cheek and ear are flushed. Clad in a semitransparent coverup, unaware that she is being watched, Leighton’s sleeper invites the viewer’s gaze. This invitation is the essential element that draws, and holds, our attention—an opportunity for uncomplicated contemplation of a beautiful body.

Frederic, Lord Leighton (British, 1830–96). Flaming June, 1895. Oil on canvas, 46 7/8 × 46 7/8 in. (119.1 × 119.1 cm). Museo de Arte de Ponce, Puerto Rico; The Luis A. Ferré Foundation, Inc.

The artist designed his portrayal to stand out among the many works at the Royal Academy. He conceived a monumental figure that nearly fills a four-foot-tall canvas, amplified by a spectacular golden frame made to his design. (The current frame is a reproduction of the lost original.) He assured the legibility and harmony of his composition by basing it on elementary geometric forms—a circle, the basic shape of the figure, within a square, the shape of the canvas. The underlying structure is repeated in the pictorial details: the woman’s draperies reiterate the curves of her limbs, and the bench’s lines echo the edges of the canvas. The painting’s most eye-catching and memorable trait is the one Leighton considered last: the brilliant orange dress. The garment’s hue complements the model’s hair and the draperies, the ensemble working together to engage our instinctive attraction to vivid color.

This invitation is the essential element that draws, and holds, our attention—an opportunity for uncomplicated contemplation of a beautiful body.

Leighton maintained that the woman’s circular pose originated with a tired model in his studio, but it is not a position that any person could hold for long, not even his favorite professional models, Dorothy Dene and Mary Lloyd. (Both may have sat for Flaming June.) Showing off his ability to depict complicated poses, Leighton choreographed an arrangement that could exist only on canvas. The woman curls in on herself, her limbs folded and flexed in intertwined angles. To achieve this spiraling effect, Leighton manipulated the figure’s proportions, most noticeably the woman’s elongated thigh, and granted her a contortionist’s flexibility. He aimed to astonish and convince with his painterly sleight of hand: a body seen through translucent, clinging fabric, the anatomy and flesh rendered with brushwork so delicate that we are beguiled into accepting the illusion.

Leighton’s emphasis on color and form aligns Flaming June with Aestheticism, a movement that promoted the idea that a work of art could concern itself exclusively with harmony and beauty and need not convey a narrative or deeper meaning. Such was Leighton’s confidence in the power of his conception that he presented it largely without a storyline or symbolic embellishments. The scene has almost no implied action and few props; although the setting and the woman’s robes evoke ancient Greece and Rome, no detail marks a specific time or place. Instead, we are in the realm of the artist’s imagination.

Marble statue of Aphrodite, 2nd century BCE. Hellenistic, Greek. Marble, H. 32", W. 9 1/2", D. 6 1/2. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Gift of Mrs. Frederick M. Stafford, on the occasion of the reinstallation of the Greek and Roman galleries, 2006 (2006.509)

Flaming June triumphed at exhibition in 1895, but its moment in the sun was short. Leighton’s death the following year heralded the end of an era. As Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, and abstraction gained prominence in Europe and the United States, the artistic vision that he proposed came to be seen by many curators, scholars, and critics as outmoded and sentimental. Flaming June seemed superficial and vapid, an invocation of sensibilities that no longer rang true; the painting fell into obscurity. We do not know where it was from 1930 until 1962, when it resurfaced on the art market without its original frame. The painting was bought from London dealer Jeremy Maas by Luis A. Ferré in 1963, for £2,000, or about $5,600. By comparison, Cézanne’s Bathers, now at The Met, sold the same year for $105,000.

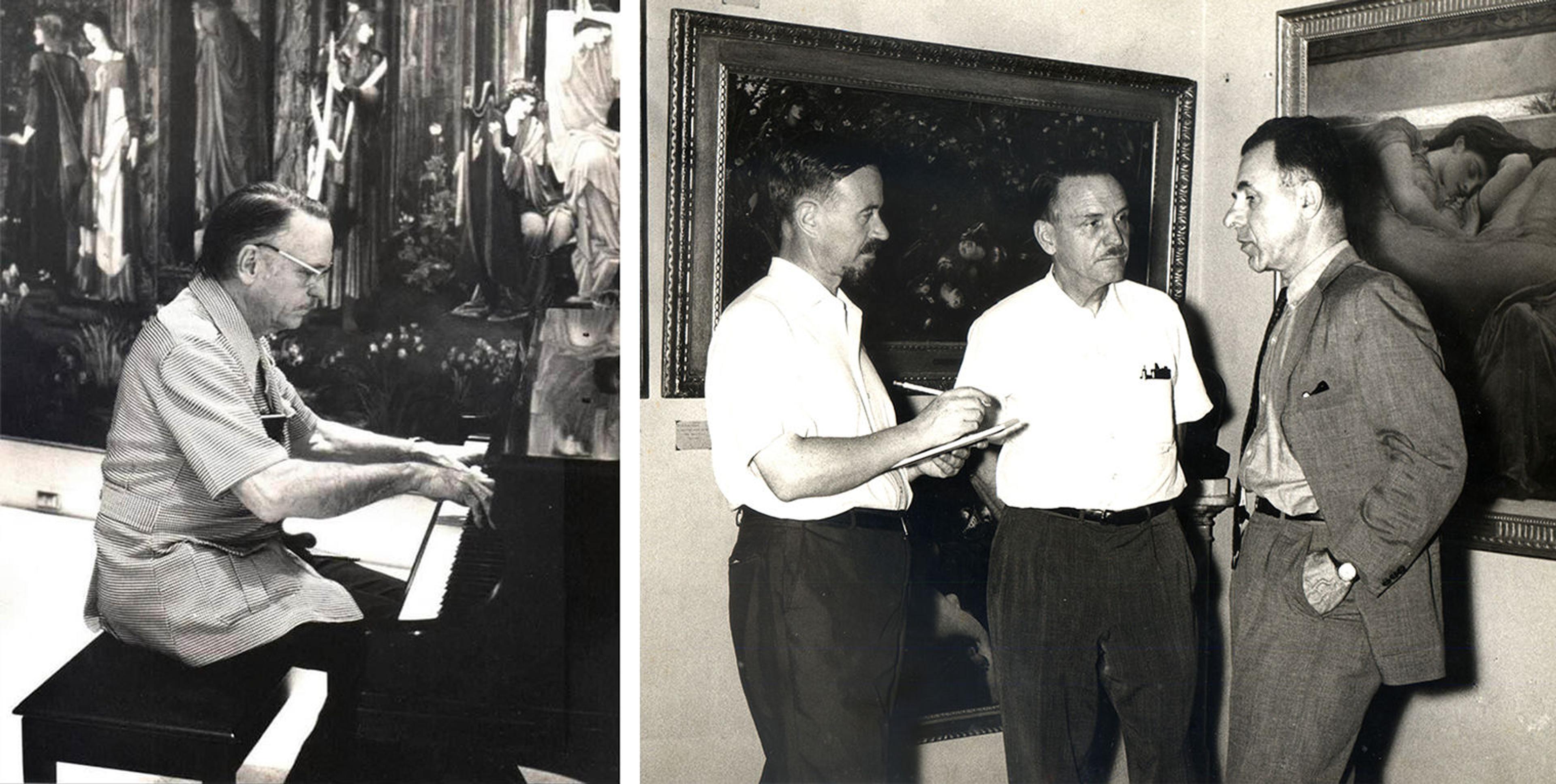

Left: Luis A. Ferré playing the piano. Right: Luis A. Ferré (Middle) with Rene Taylor and Julius Held at the Museo de Arte de Ponce. Both images courtesy Museo de Arte de Ponce

Ferré, who founded the Museo de Arte de Ponce in the 1950s to celebrate and enrich Puerto Rico’s artistic culture, sought hidden gems to bolster the museum’s collection. His estimation that Flaming June would stand the test of time has been confirmed in recent decades. As taste has changed and broadened, figural representation and traditional painting styles have regained status as serious undertakings. Imagery of opulent and idealized beauty is ubiquitous. With this shift, Flaming June is again ascendant: the painting is a beloved centerpiece of, and ambassador for, the Museo de Art de Ponce and is admired globally. Although the basic terms of Flaming June’s appeal are the same as they were in 1895, the audience for the painting, and the scope of responses to it, is today wider and more varied than Leighton could have ever imagined.