Egypt is in my history and in my heart.

My father was a civil engineer who worked internationally. He traveled to many parts of the world, heading up projects in various countries in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. I visited him in Egypt when he was involved with the rebuilding of Port Said. He lived in Cairo at the time, and Anwar El-Sadat was president. While I was there, I traveled throughout Egypt on my own and sometimes with a friend. Being in my youth (early twenties) gave me a perspective that was very different from my three subsequent visits. While I have traveled to Europe, sub-Saharan Africa, and Peru on other trips, Egypt was the only country I have visited where I blended in, to a degree, because of my general appearance. If they didn’t think I was from there (and most didn’t), they assumed I was from a neighboring country. They’d ask me: “Where are you from?” I’d reply “America.” Looking confused or as if I was hiding something or just a bit dumb, they’d ask me, “But where are you REALLY from?” When I’d reply, “The United States,” they’d pause and politely say, “Ask your father!”

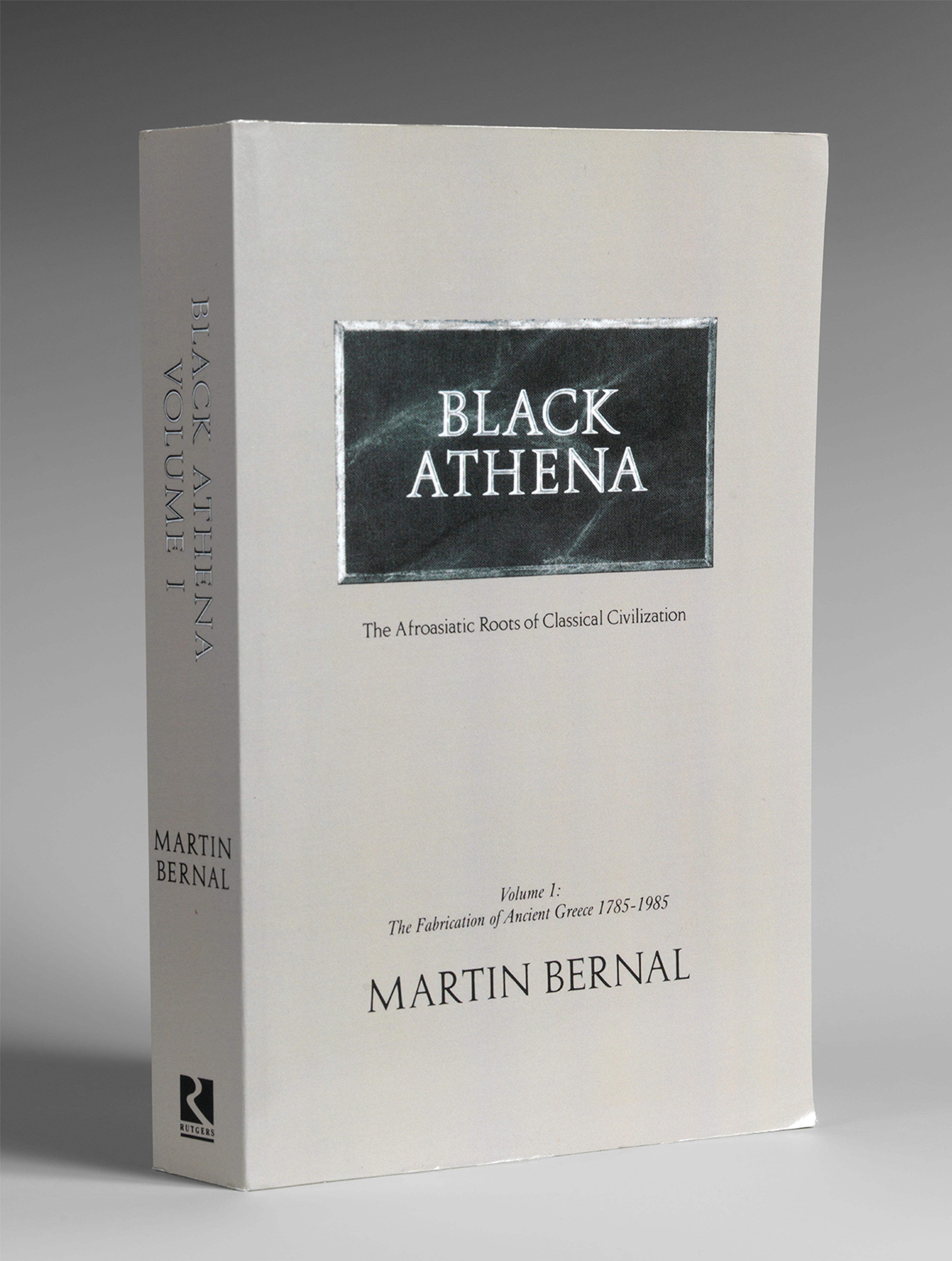

Cover of Black Athena (1987) by Martin Bernal

After that initial experience in Egypt, I was hooked. When Martin Bernal’s book Black Athena (1987) was on the bookshelves for the first time, I clamored for it. While I did not weigh in on the thesis of the book, I felt strongly that the story of that region had not been objectively told in previous tomes on the subject. I believed that only one perspective had been codified through an imperfect and sometimes historically racist lens. Black Athena offered a different viewpoint to revisit, test, and contest what had become the sleeping norm.

Fred Wilson (American, born 1954) Grey Area (Brown version), 1993 Pigment, plaster, and wood, overall: 20 x 84 in. (50.8 x 213.4 cm) Brooklyn Museum, Bequest of William K. Jacobs, Jr. and bequest of Richard J. Kempe, by exchange (2008.6a–j)

It must be understood that my early works related to Egypt as well as my works in the 1992 Cairo Biennial and the 1993 Whitney Biennial were a way to reveal the varying interpretations of this history—ancient, colonial, and contemporary. I laid them out there for audiences to digest and see in relationship to each other, as prior to the Internet and the defining DNA test the various perspectives never collided. It is my belief that, as the science of DNA has now revealed, the ancient Egyptians were unique: their DNA was like that of no other group of humans, then or now. In Grey Area and Grey Area (Brown version) (both 1993), for example, I intended neither to present or espouse a final thesis. I just found it fascinating that so many points of view were occurring at the same time.

Gallery view of Flight into Egypt with Fred Wilson’s Grey Area (Brown version), 1993

This essay is adapted from the catalogue Flight into Egypt: Black Artists and Ancient Egypt 1876–Now, which accompanies an exhibition on view through February 17, 2025.