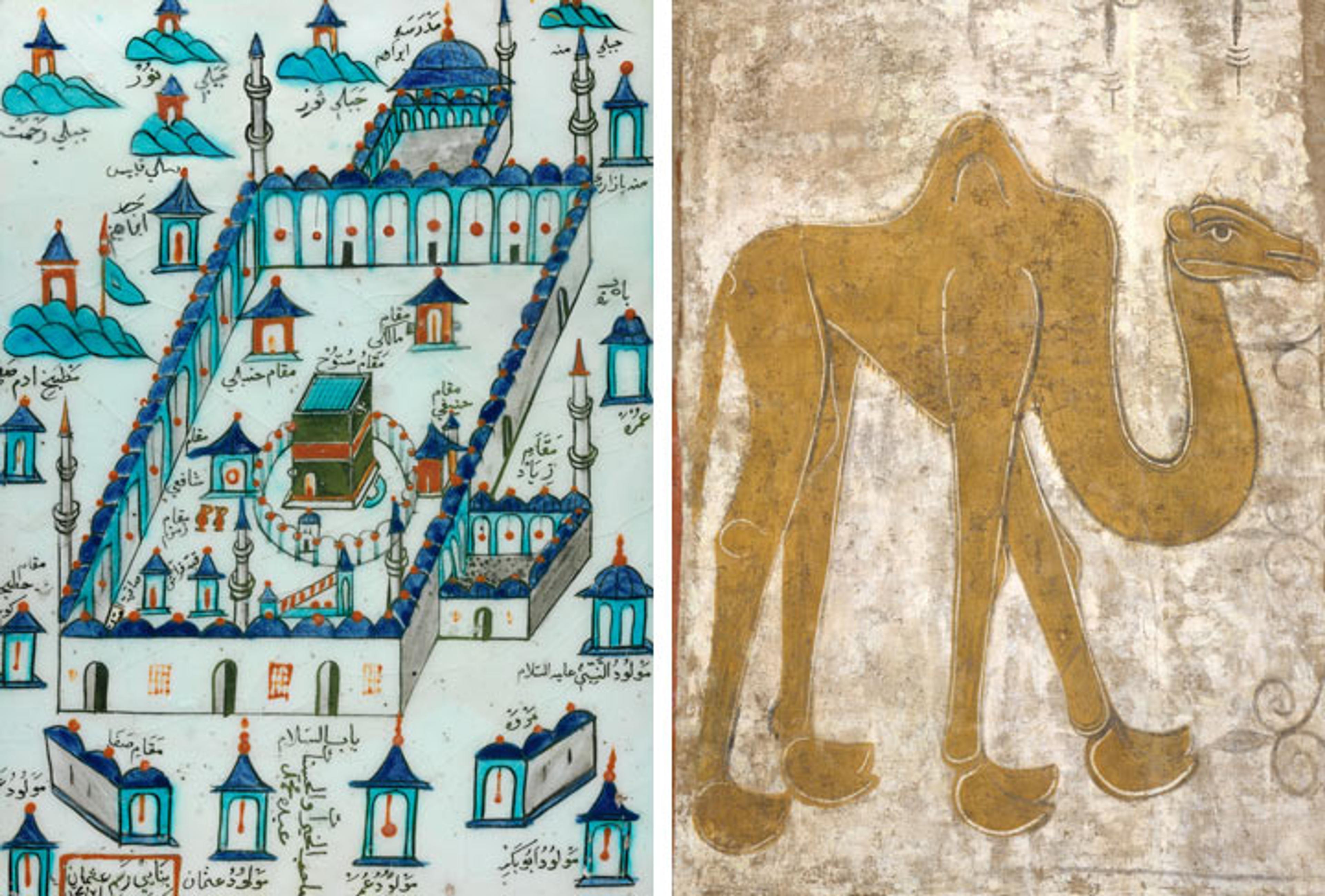

Left: Fig. 1. Osman Ibn Mehmed (Turkish, active first half 18th century). Ka'ba tile, ca. 1720–30. Made in Turkey, Istanbul, Tekfur Sarayi (workshop). Islamic. Stonepaste; polychrome painted under transparent glaze, H: 13.8 in. (35 cm), W: 10.3 in. (26.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of John and Fausta Eskenazi, in memory of Victor H. Eskenazi, 2012 (2012.337). Right: Fig. 2. Camel (detail), first half 12th century (possibly 1129–34). Made in Castile-León, Spain. Fresco transferred to canvas, 97 x 53 1/2 in. (246.4 x 135.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection 1961 (61.219)

«In October members of the Islamic faith welcomed the start of their new year within the lunar hijri calendar. Bidding farewell to the year that passed, millions of Muslims performed hajj—a pilgrimage ritual in which every Muslim must participate at least once during their lifetime if they are financially and physically capable to do so. In a 2012 blog post, I provided details on the ritual itself and the holy sites of Mecca and Medina, visual representations of which figure predominantly in material culture from the Islamic world (fig. 1). This time around I am introducing a participant in the hajj journey who sometimes appears in these representations and played an important role in the overall pilgrimage experience: the camel.»

The camel (al-jamal) has been integral to human activity throughout history. It was a source of meat, milk, and skin for making leather; its urine, according to prophetic traditions, was used for curative proposes; and it served as an unparalleled means of transportation. Camels traversed far and wide, from Asia in the east all the way to Spain in the west, their steps marking the length of the Silk Road. Representations of camels across different media are witnesses to the animal's status as a desired, often exotic commodity.

Left: Fig. 3. Turquoise figurine in the form of a camel carrying Palanquin and two riders, 12th–early 13th century. Attributed to probably Iraq or Iran. Islamic. Stonepaste; molded in sections, glazed in turquoise, H. 7 11/16 in. (19.5 cm), W. 5 9/16 in. (14.1 cm), D. 2 9/16 in. (6.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fletcher Fund 1964 (64.59)

Inspiring pre-Islamic and classical Arabic poetry, the robust camel was a reference to patience, strength, obedience, and endurance. In the Islamic tradition, when God sought to exemplify his might and the wonders of his creation, it was the camel that filled the role. A passage in the Qur'an, 88:17, notes that God asked, "Do they not look at the camels, how they are created?"

Saddled, decorated, and ridden, the Arabian camel (one-humped dromedary) carried commodities and people across distances both short and long. In addition to their role in commerce and travel, they were integral to social events. As part of wedding festivities, women were ceremoniously transported to their new home in a hawdaj, or a canopy-like structure mounted on the camel's back (fig. 3).

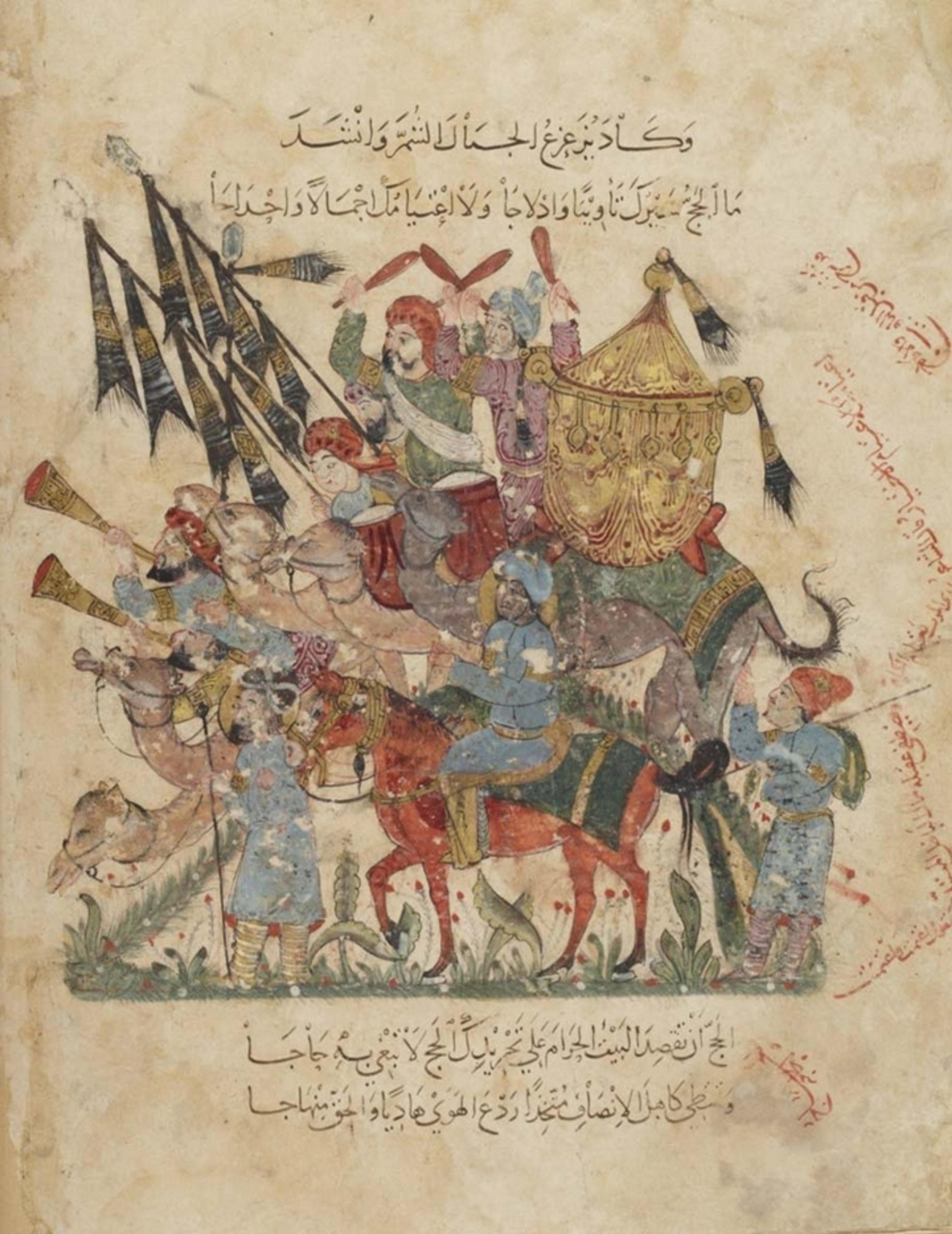

Right: Fig. 4. The camel Mabrouk and his caretaker in the mahmal of 1920, from Sayyid Hamid, "'Nabil' wa-'Mabruk' Hamilan Kaswat al-Ka ba . . . Muwasifat Khassa li-Ikhtiyarha (Siwwar)," Moheet.com, published March 15, 2014.

The hawdaj and the camel have also been associated with another festivity related to hajj: the dispatch of the kiswa—a highly elaborate textile usually made of gold- and silver-embroidered silk, the production of which could take up to a year. Each year it was transported in a ceremonial caravan featuring an empty embroidered hawdaj, called a mahmal, to cover the holy stone of Ka'ba in Mecca. Jamal al-mahmal, or the camel that carried the empty hawdaj, was carefully selected for this honorable task. As English observer Arthur Wavel described in his book, A Modern Pilgrim in Mecca:

A great crowd assembles to see the Mahmal off, and it is escorted for some distance by the governor and principal dignitaries en grande tenue. The camel that has the honour of carrying it is of great size, and, I believe, of the highest breeding.

Indicative of the camel's status is that it was given a special name and even an attendant who was commissioned to take the closest of care of the animal. In the hajj of 1920, two camels, Nabil (honorable) and Mabrouk (blessed), were chosen to carry the mahmal. So concerned was the attendant with their comfort that he would breathe cigarette smoke in their nostrils to help calm their nerves. As the camels proceeded along the procession route, the waiting crowds would blow smoke as well, a tradition that continues today in Egypt's countryside.

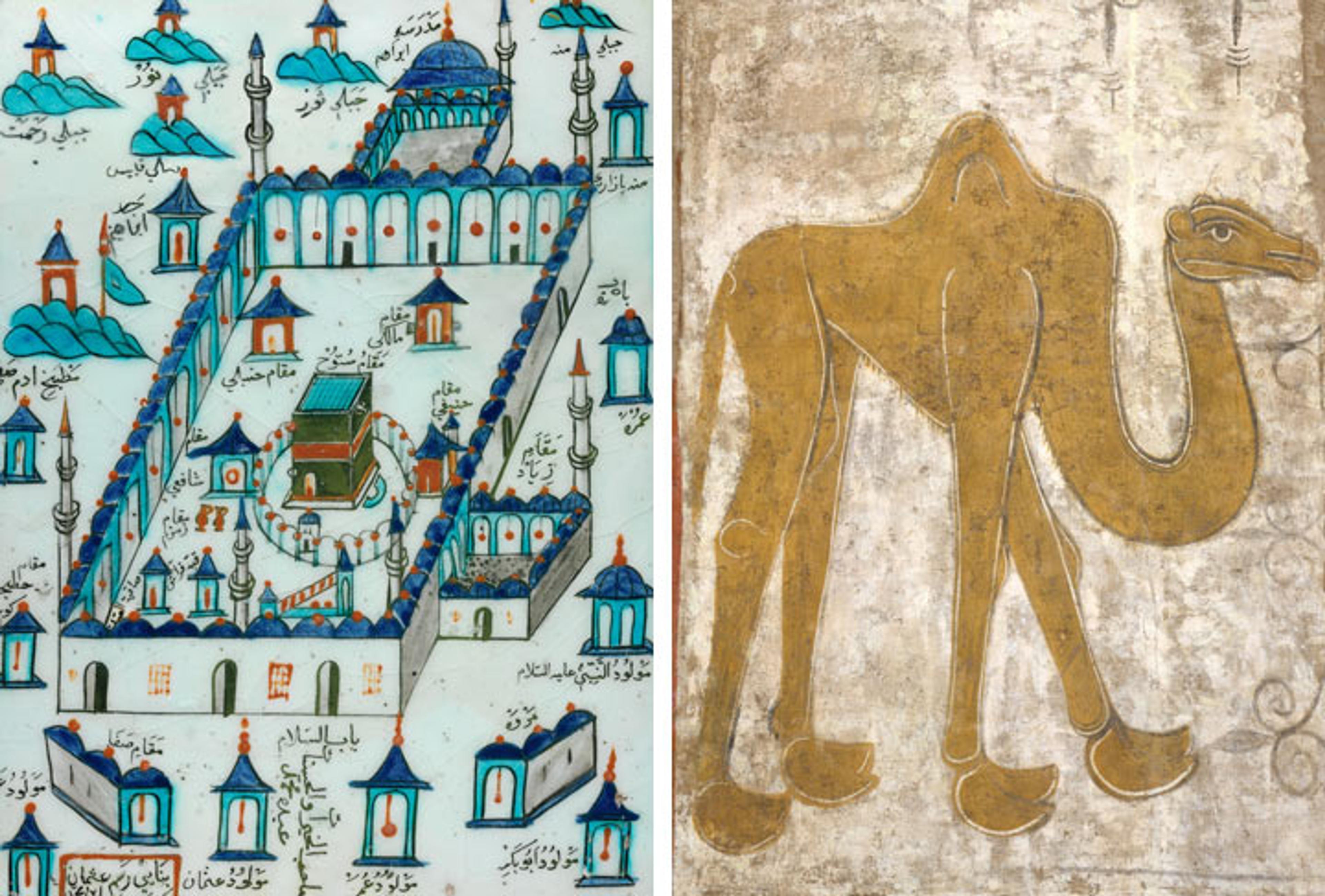

Fig. 5. Maqamat al-Hariri. Abu Zayd on Hajj and the Caravan of Pilgrimage (Maqama 31, fol. 94v), ca. 1237 A.D. Iraq. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Arabe 5847

Throughout Islamic history, the ceremony attracted commoners, elites, and foreign dignitaries alike. The mahmal procession featured a fluid convergence of people and objects moving through space, creating a kind of performative spectacle such as the one depicted in maqama 31 in the 13th-century illustrated manuscript of Maqamat al-Hariri (fig. 5). This tradition outlived al-Hariri himself, as seen in later photographs of this event.

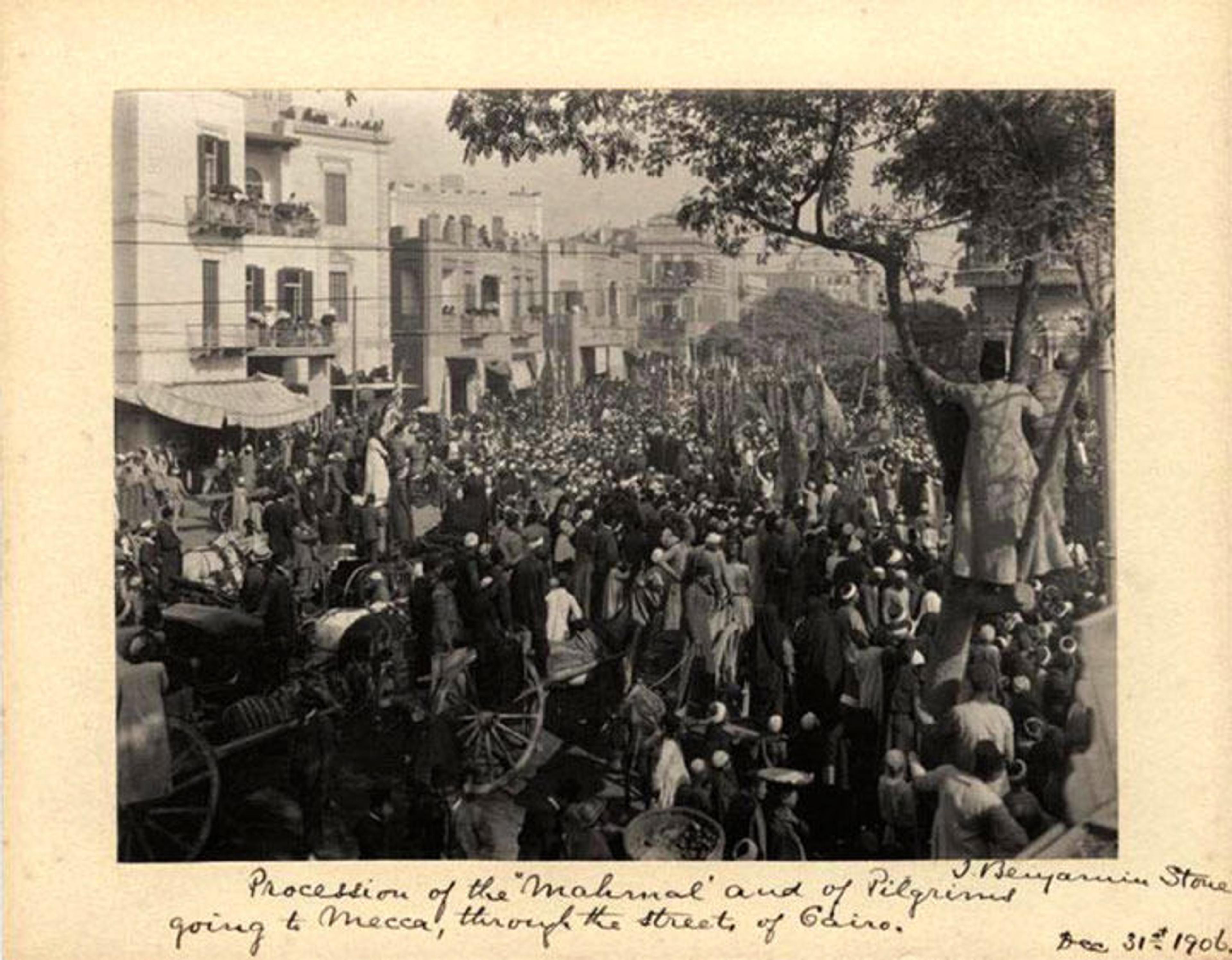

Fig. 6. The parade in the streets of Cairo on December 3, 1906, from Muhi Ziyada, Kiswat al-Ka'ba . . . al-Sharaf al-'Azim, Itfarag, published September 10, 2016.

In fact, from the Mamluk period (1250–1517) to the early 1960s, Egypt had the task of sending the kiswa to Mecca. Sultans, Khedives, and presidents embraced this role, ensuring that the honorable kiswa was intricately designed and safely dispatched to the Holy Land. As alluded to earlier, people would stand in the streets for hours so as not to miss sight of the mahmal sharif (honorable camel), the travels of which was reported by newspapers (fig. 6).

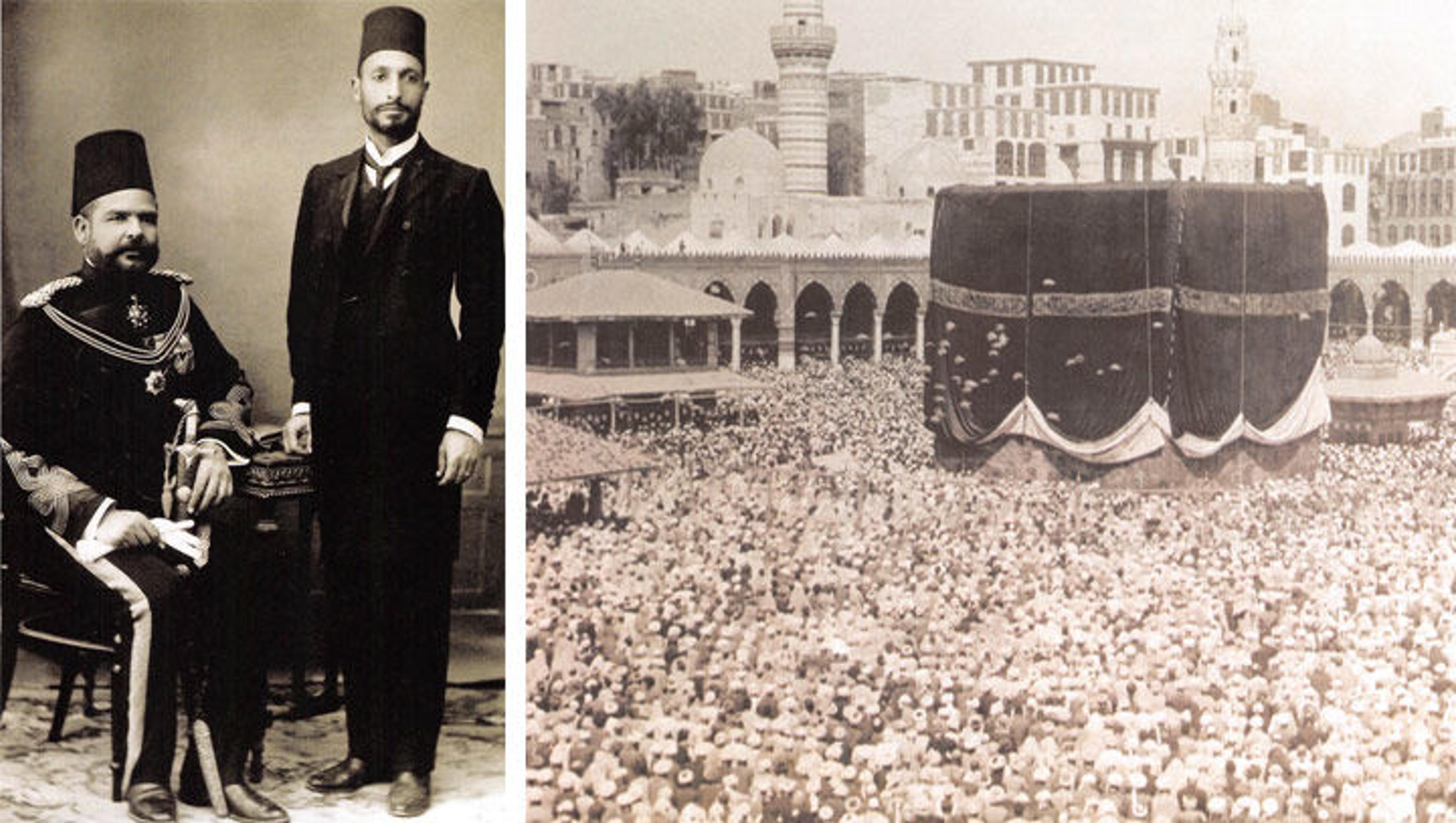

Left: Fig. 7. Amir al-Hajj Ibrahim Pasha Ref'at (left) and Mohamed Effendi al-Sa'udi (right), from Farid Kioumgi and Robert Graham, Musawwir fi al-Hajj, trans. Surri Khuris (Abu Dhabi: Kalima, 2012), 18. Right: Fig. 8. The new kiswa covering the Ka'ba during the hajj rituals. Photo by Muhammed Effendi, ibid., 77.

To ensure success, Egypt's rulers commissioned the best officials to lead the procession. Amir al-Hajj Ibrahim Pasha Ref'at—photographed, above left, after returning to Egypt upon completion of the 1904 procession and the hajj ritual—was one such trusted figure (fig. 7). When the official and his entourage finally arrived in Arabia, they were greeted by both an Egyptian diplomat stationed in Arabia as well as local dignitaries. Pictured above with Ref'at, the young Muhammad Effendi al-Sa'udi—like his earlier peer Ibn Jubayr al-Andalusi (d. 1217), the polymath author of Ibn Jubayr's Journeys—offered an enthusiastic account of his trip to Mecca that was amplified by his use of a camera. He was an early photographer of the hajj and documented sites that are now lost to history (fig. 8).

Lost to the present is the mahmal tradition, and the kiswa, though still in use, is manufactured in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. As for the camel, its role as the great transporter has been overtaken by the plane, with today's annual pilgrims now flying rather than walking the distances separating them from the Holy Land. Those who cannot make the journey can now witness the hajj in real time through platforms such as Snapchat. These digital experiences are ephemeral, however, since the pictures and videos published to Snapchat disappear once they are viewed by users. Now instead of waiting for the return of the camel and the pilgrims' stories, we wait for the hashtag #meccalive each year in order to witness the hajj (fig. 9). Hence we have gone from the camel to Snapchat!

Left: Fig. 9. Muslim pilgrims circle the Ka'aba in Mecca, from Aisha Gani, "Mecca Worshippers Stream Their Stories Live on Snapchat," The Guardian, published July 14, 2015.