What happens when our most intimate possessions end up in art museums?

Blankets comfort and keep us warm. They accompany us through our lives. They are keepers of some of our most intimate stories. We look at a group of artists who harness this power of blankets and quilts as totems for memory, community, and cultural survival.

Read the illustrated transcript below.

Listen and subscribe to Immaterial on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube, Amazon Music, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Season 2 of Immaterial is made possible by Dasha Zhukova Niarchos. Additional support is provided by the Zodiac Fund.

Transcript

LORETTA PETTWAY BENNETT: My name is Loretta Pettway Bennett. I am in Gee’s Bend, Alabama where I was born and raised.

CAMILLE DUNGY: Loretta grew up surrounded by quilts.

PETTWAY BENNETT: My mother, Qunnie, she learned quilting from her mother, and same in turn, my grandmother learned it from her mother.

DUNGY: For years people had bought the quilts made by the women in her small community. But one particular art collector took a great interest…

PETTWAY BENNETT: He said that they were gonna be in museums. There was a big exhibition of the quilts.

DUNGY: Dozens of women from the community were invited to an event in Houston, Texas. This collector had rented buses and wanted the women and their families to see their work displayed at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

PETTWAY BENNETT: Of course, none of us believed it. But we had to see for ourselves.

DUNGY: That’s how Loretta found herself in a hushed, white walled space, looking at a familiar object in a strange context. Dozens of them actually.

View of Housetop by Qunnie Pettway (at right) in The Quilts of Gee's Bend. The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, September 2002. Image © Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

PETTWAY BENNETT: When we got there and saw the quilts on the wall and hanging in the museum, they looked different. You know?

DUNGY: Loretta’s mother’s quilts were abstract and idiosyncratic. Wild pinwheels and lightning bolts of color. And they were made of scraps.

Quilts by Qunnie Pettway and her daughter Loretta Pettway Bennett. Left: Qunnie Pettway (American, 1943–2010). Housetop, ca. 1975. Corduroy, 82 x 74 in (208.3 x 188 cm). Souls Grown Deep Foundation © Estate of Qunnie Pettway. Photo by Stephen Pitkin/Pitkin Studio Right: Loretta Pettway Bennett (American, b. 1960). Blocks And Strips, 2004. Denim and cotton, 74 x 64 in (188 x 162.6 cm). Souls Grown Deep Foundation © Loretta Pettway Bennett. Photo by Stephen Pitkin/Pitkin Studio

PETTWAY BENNETT: It was whatever the womens could find and put together, and this would have been old dress tails, pants, the back of pants and shirts that was worn out, and that's what the women used to make. We refer to them as ugly quilts.

DUNGY: These were quilts made by dozens of women from her small hometown. In this case, by her mother…

PETTWAY BENNETT: And I just remember her looking at her quilt on the wall. And she went to touch the quilt, and there was someone standing next to the quilt and saying, oh, oh, you can't touch it. You know? And I'm like, you can't touch the quilt? This quilt been on the floor! We've been laying on the quilt. Now we can't touch the quilt?

PETTWAY BENNETT: She just wanted to touch it to make sure it was real.

DUNGY: Loretta couldn’t help but ask: What were these quilts doing in a fine art museum—with a guard watching over them?

PETTWAY BENNETT: We thought we're just making quilts, because we couldn't see no art in them. We just saw necessity and warmth, keeping ourselves warm. And so, it was a mind blowing thing. At first, it was hard to wrap our heads around it.

[MUSIC]

DUNGY: From The Metropolitan Museum of Art, this is Immaterial. I’m Camille Dungy.

This is an episode about blankets and quilts.

When I say quilt or blanket, is there a special one that comes to mind? Does it bring you back to a very specific time and place? For me it's a quilt made by my grandfather, who was a tailor by trade. It must have been pieced together in the late seventies judging by the colors and patterns of the fabric, including an orange and brown swatch from one of my favorite dresses when I was six. My grandfather wouldn’t have lived many more years after he made this quilt for my sister and me, but still, all these decades later, I have this warm comfort he handcrafted.

Blankets are not the same as quilts.

Blankets are a single layer of fabric that's been woven or knitted. Quilts, however, are made of three layers: a top made with small pieces of fabric sewn together to form a pattern or design; an inner layer of cotton or wool batting for warmth; and a backing fabric. A quilt becomes a quilt when all three layers are stitched together.

Blankets and quilts carry memories, histories, stories, and meaning. They are often given as gifts. They see generations of use.

In this episode, we're going to look at two examples of quilts and blankets: The people who made them…and the stories they carry.

—

[MUSIC]

DUNGY: The artist Marie Watt has vivid childhood memories of a few wool blankets and quilts.

MARIE WATT: Those blankets, they were used for picnics and they were used for building forts, and we used them for covering up after skiing. It's funny, I feel like cars in the seventies, they just weren't very well insulated and so these blankets, they were always available and at the ready.

I do think of blankets as being kind of protective and shield-like, and they keep us warm.

DUNGY: Marie’s taking us through her studio in Portland, Oregon.

[WALKING THROUGH STUDIO]

WATT: I can take you over there. There’s racks and racks of blankets back there. We’re running out of racks actually.

DUNGY: At first glance, the space looks like a laundromat, with colorful blankets packed into clear, plastic bags on tall, metal shelves.

WATT: They’ve all been washed. They’re kind of grouped by color.

DUNGY: Marie is an artist, and these blankets are her raw material.

WATT: I do like talk about it as a tube of paint. But actually it’s almost better than a tube of paint because there’s no blanket like that blanket.

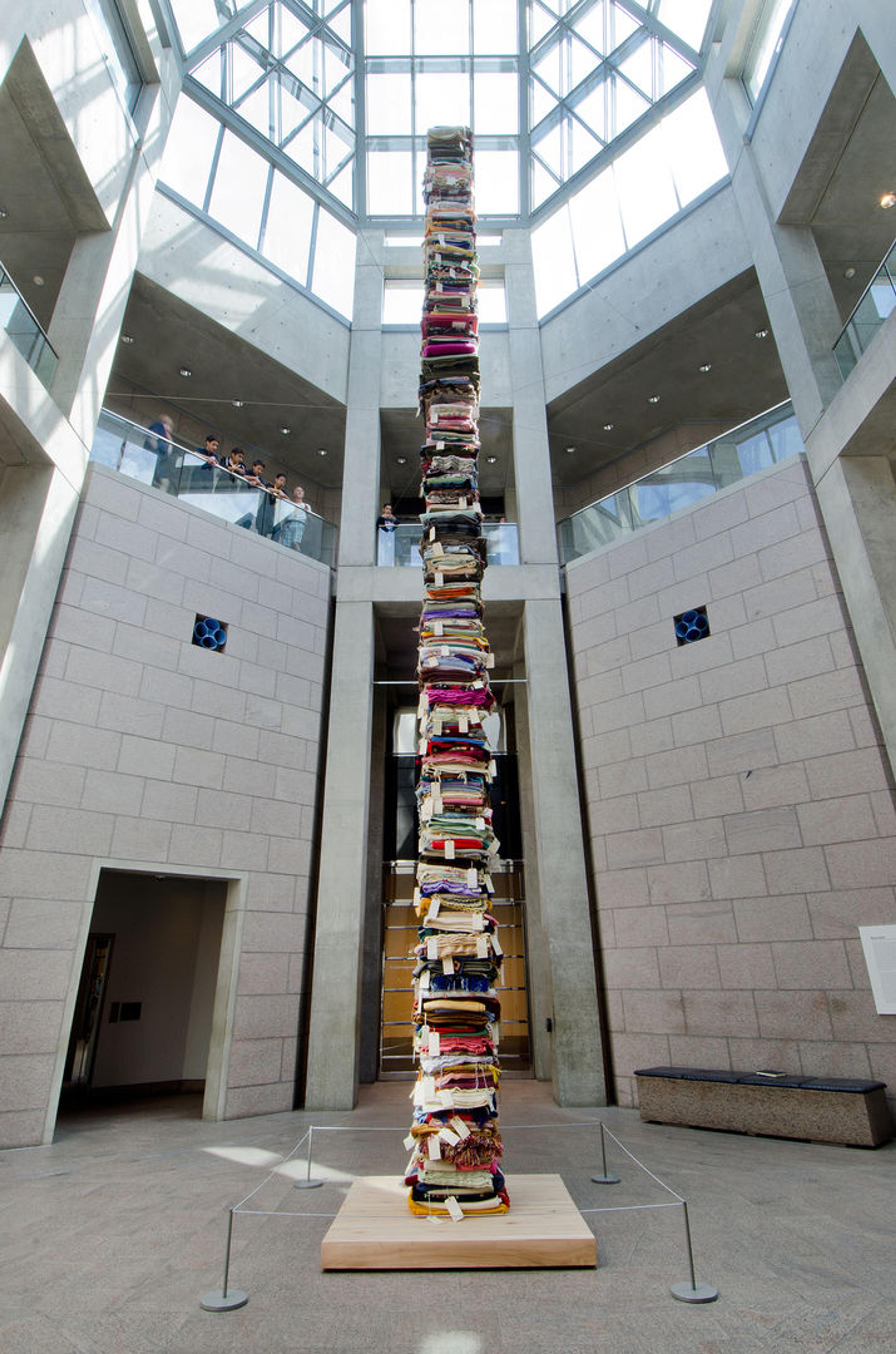

DUNGY: Imagine a stack of folded blankets—maybe five or so. Freshly cleaned, ready to be put away. Now, imagine another blanket added on top of the stack. Now another. And another two. Then another five, until the stack towers above you. A skyscraper built of blankets.

This is what Marie’s early sculptures look like—sky high totems of folded blankets.

The idea of using blankets for her sculptures—and specifically wool blankets—came after college.

Marie Watt (Seneca, b. 1967). Blanket Stories: Seven Generations, Adawe, Hearth, 2013. Wool blankets, manila tags, thread, cedar base, 36 ft. x 20 in. x 20 in. (1097.3 x 50.8 x 50.8 cm). Collection of the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, CA © Marie Watt. Photo by National Gallery of Canada

WATT: Wool blankets sort of stay around in our lives and they're kind of passed on. It's the worn ones that are so beautiful to me and really speak to me because they talk about this history of use.

DUNGY: She spent time scouring thrift stores for old woolen blankets. Ones with tears and holes that conjured car rides and blanket forts of yesteryear. And she imagined all of the people who once held these blankets and lived alongside them.

WATT: I think one of the things that I realized is the degree to which this humble everyday object was a touchstone for our experiences.

DUNGY: At a certain point in her career, rather than just imagining the stories contained in the blankets she collected, she decided…

WATT: To invite people to share a blanket and a blanket story and sort of build sculptures that were collaboratively realized.

DUNGY: Marie partnered with museums to put the word out that she was interested in collecting blankets and their stories. As she did this around the country, she collected and cataloged a wide array of them. One sticks out to Marie.

WATT: There was a blanket that came in from this gentleman named Peter Kubicek, and he had been in a concentration camp. And when the camp was liberated, didn't know where he would go. And so he brought this Nazi-issued blanket with him because he needed a bedroll.

Nazi-issued blanket belonging to Peter Kubicek, part of Marie Watt's Dwelling, 2006. Wool, manila tag. Photo by Marie Watt Studio

I like that an object as humble as a blanket can be the conveyor of history. I think it’s powerful that cloth can do that.

DUNGY: Marie’s towering blanket sculptures were crafted with the help of these individuals and their stories. They represented a vast group of people and their life experiences.

Then, Marie began to take this practice a step further. She took these blankets, cut them up, and pieced them together into quilts—charting a map of the collected stories onto new, remixed blankets. Sewn together all by hand.

WATT: I was really interested in not using a sewing machine because I like the visibility of one's hand and stitch in the work.

I quickly realized that if I was going to finish the scope of work that I was trying to accomplish, I needed to kind of change up the way I was doing things. And so I started thinking about hosting sewing circles.

DUNGY: This was an important moment for Marie. Her work with blankets allowed her to collaborate with people and incorporate stories of their lives into a new form.

Marie thought of these as sewing circles. But not, she clarifies, as sewing bees. Marie is a member of the Seneca Nation of Indians. Her mom grew up on the Cattaraugus Reservation, part of the Seneca Nation, and told of missionaries organizing sewing bees as a sly way to convert Native American women and girls to Christianity.

Marie’s sewing circles, then, are a way she says she brings together strangers who share stories. And as a result, new connections are formed and a new story is created. Each voice is added to a chorus. The quilts made during these sewing circles contain stories of their past uses, but also all the stories told during these gatherings.

For a time, one of Marie’s collaborative quilts hung on a gallery wall in The Met. The work is called Untitled (Dreamcatcher). To me it looks like an intricate, multi-colored spider web. It’s made up of hundreds of small diamond patches expanding outward to create concentric circles.

Marie Watt (Seneca, b. 1967). Untitled (Dream Catcher), 2014. Reclaimed wool blankets, satin binding, and thread, 9 ft. 11 1/2 in. x 8 ft. 3 1/2 in. x 11 in. (303.5 x 252.7 x 27.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Morris K. Jesup Fund, 2021 (2021.46) © Marie Watt

If you look closely, each diamond has been carefully stitched by hand, a testament to the people and stories that went into this work.

ALLY BARLOW: There was, you know, areas that had been obviously stitched by different people.

DUNGY: That’s textiles conservator Ally Barlow. When she looked at Marie’s work, at the individual stitches, she imagined all those people who played a role in its creation. Even if we don’t know their names.

BARLOW: And in the case of Marie Watt's work, what's so interesting is that you have the layers of stories, right? So you have the blankets themselves that were made by unknown makers, you know, normally in an industrial setting for those blankets that she uses. And they've been used by, again, an unknown person who's used them, but left signs of that use, right?

So it's worn in certain areas where there was more handling. And then Marie brings them together in a community sewing circle, where again, all of the different hands aren't named. But when I was working on bringing that piece in and seeing it closely, you could see the different hands by the way that they could stitch, right?

DUNGY: As Marie said, these blankets are touchstones for our experiences. That's what draws us to them. That is what she is trying to evoke.

WATT: I think one thing I'm really interested in doing in the work that I make is creating that avenue for engagement that's in our DNA, but that I think sometimes we forget about when we are in museums because things are behind glass and you can't touch it.

A favorite story that I also think connects to this notion of how blankets call to us or call us. I have a curator friend at the Seattle Art Museum, and she called me one day and said, Marie, I'm calling because I have a security report to share with you.

DUNGY: Marie had one of her blanket sculptures displayed at the museum at the time.

WATT: And the story goes that a child hugged my sculpture. And I just thought, Oh, that's like the best security report ever is to like, have somebody hug your artwork. But I think that's also just how, I don’t know, resonant our connection with certain materials are, right?

And we take those relationships for granted. And yet if our world was stripped of these materials, we wouldn't know how to locate ourselves and our stories.

DUNGY: After the break, we’ll return to the story of quiltmakers from Gee’s Bend, Alabama and hear how quilts act as emblems of community and survival.

—

[MUSIC]

PETTWAY BENNETT: It was colder inside than it was outside, felt like.

DUNGY: We met Loretta Pettway Bennett at the beginning of the episode. She was born and raised in Gee's Bend, Alabama. Don't let some idea of the hot, humid south fool you. The south can get quite bitter, and damp, with temperatures dropping below freezing. In the winter, Loretta felt like there was little that stood between her and the cold.

PETTWAY BENNETT: The house, it just didn't have any insulation. They had wood windows. Even though I was born in the sixties, we had wooden windows.

DUNGY: Without any glass in the windows, there was one thing that helped…

PETTWAY BENNETT: We had to use quilts for hanging up at those windows, the doors, and on the floor. And so anything that you got your hand on that you could sew and put together, it was turned into a quilt. I can remember having, like, five quilts on the bed. You can barely turn over.

DUNGY: Lousiana Bendolph also grew up in Gee's Bend.

LOUISIANA BENDOLPH: They were for necessity. They was trying to make it warm for the family. ‘Cause I could tell you it was really cold. It used to be really, really cold in Gee's Bend.

Louisiana P. Bendolph (American, b. 1960). Housetop quilt, 2003. Cotton-polyester blend, 98 in. x 66 5/8 in. (248.9 x 169.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection, 2014 (2014.548.41) © 2024 Louisiana Bendolph / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo by Stephen Pitkin/Pitkin Studio

DUNGY: Like Loretta, many of Louisiana’s childhood memories involve quilts. One early memory for Louisiana…sitting under the quilts as they were made.

BENDOLPH: We would sit under there and we would watch the needles go in and out.

PETTWAY BENNETT: What I call fun time, because I got to play at my mother’s feet and my first memory, I was five or six, when I was just threading needles, for my mom and grandmother and aunties.

DUNGY: This learning on the job was a deep tradition in Gee's Bend.

BENDOLPH: This was something I had inherited from my great-grandmother, my mom, my aunts, from seeing them do it. And then it was like, so who am I to say no?

Lucy Mooney in her living room with granddaughters Lucy P. Pettway (now married to quiltmaker Annie E. Pettway's son Willie Quill) and Bertha Pettway. Arthur Rothstein (American, 1915–1985). Sewing a quilt. Gees Bend, Alabama, 1937. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives

DUNGY: Gee’s Bend is a tiny town.

PETTWAY BENNETT: You know just about everyone. You will find it very quiet. Uh, no lights, no street lights, stop lights, or anything like that. Gee's Bend is surrounded by water. So it's kinda like a little horseshoe. So named after Joseph Gee. It was in the bend of the river.

DUNGY: Loretta Pettway Bennett, and most of the other residents of Gee's Bend, are the direct descendants of the enslaved people who worked the cotton plantation established by Joseph Gee in 1816.

PETTWAY BENNETT: Joseph Gee came down from North Carolina, and so he owed his nephew, Mark Pettway, some money. And so Mark Pettway and a hundred slaves came down to Gee's Bend.

So, every slave that came on to this plantation, Gee's Bend, everyone became Pettway. And so we continue with that name till today.

DUNGY: After the Civil War, the Pettway ancestors remained on the plantation and worked as sharecroppers.

PETTWAY BENNETT: Farming was a big part of, when I was growing up here in Gee's Bend. I picked cotton. We had peas and okra and corn, peanuts and squash, you know, cattles and goats, chickens and ducks and things like pigs.

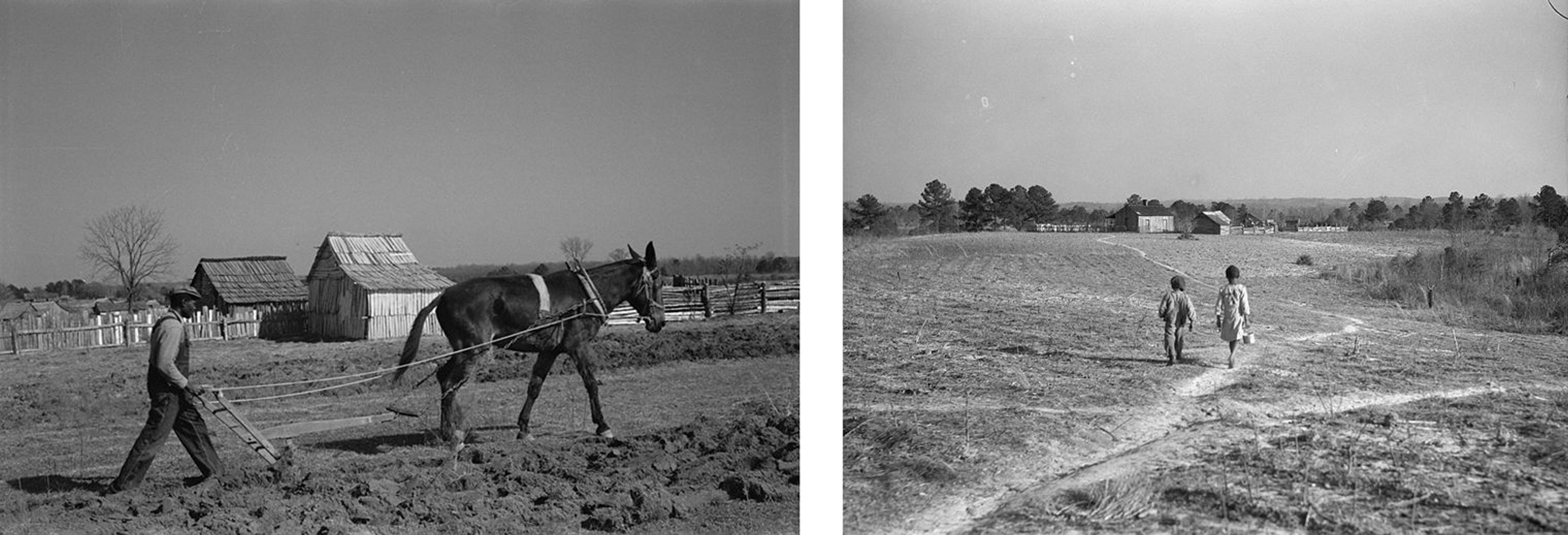

Left: Houston Kennedy, husband of Mary Elizabeth Kennedy and brother of Pearlie Pettway. Arthur Rothstein (American, 1915–1985). Plowing at Gee's Bend, Wilcox County, Alabama, 1937. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives. Right: Lovett and Lucastle, siblings of Arlonzia Pettway and children of Missouri and Nathaniel Pettway, walking to their house on the Pettway plantation land. Arthur Rothstein (American, 1915–1985). Footpaths across the field connect the cabins. Gees Bend, Alabama, 1937. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives

DUNGY: In the 1930s, the price of cotton crashed. As part of a Great Depression intervention, the federal government purchased ten thousand acres, and provided loans. These enabled residents to acquire and farm the land worked by their ancestors. It's the reason that so many residents of Gee’s Bend stayed, while hundreds of thousands of African Americans from the rural south were leaving in what we now call the Great Migration.

When Loretta and Louisiana were young, Gee's Bend's history meant that most people still farmed. And quilts were everywhere…

PETTWAY BENNETT: Made out of those burlap sacks, fertilizer sacks, flour sacks. Anything that you can sew or cut in, and they would sew it together and make a quilt out of it. Nothing was thrown away. You know? They used just about anything that they could get their hands on.

DUNGY: But just because they used any thing doesn't mean the quilts looked just any way…

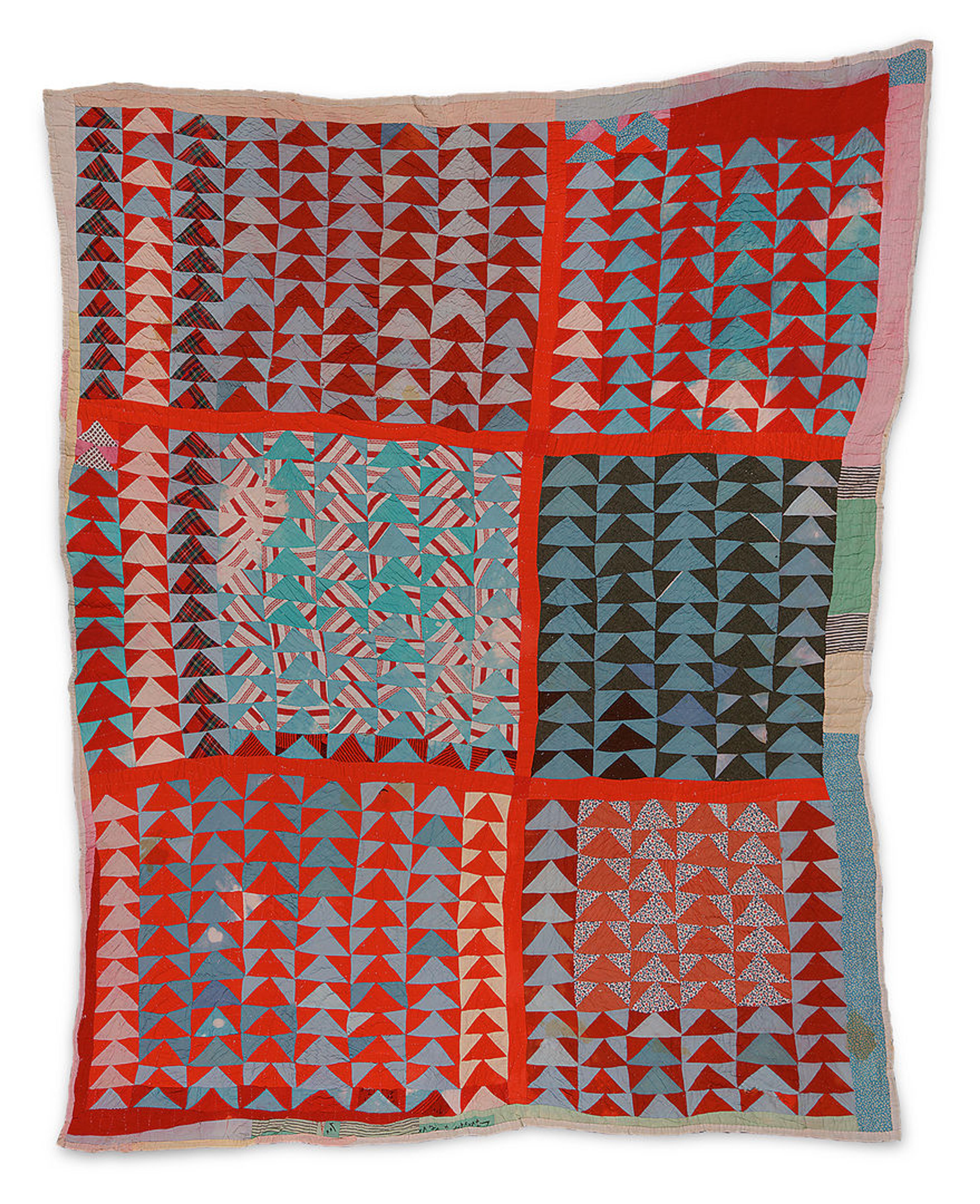

BENDOLPH: Because anything you do, you want it to look pretty to you and basically that's what they was doing. They used what they had and, and it just so happened it turned out to be, be beautiful. I mean, you look at them, like my great-grandmother quilt, Annie E. Pettway, I look at the triangles and I'm like, man, those colors I would have never put together, but they look, I mean, it looked really good.

Annie E. Pettway (American, 1904–1971). Flying Geese Variation Quilt, ca. 1935. Cotton and wool, 86 x 71 in. (218.4 x 180.3 cm). Philadelphia Museum of Art: Purchased with the Phoebe W. Haas Fund for Costume and Textiles, and gift of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection, 2017-229-5 © Estate of Annie E. Pettway / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo by Stephen Pitkin/Pitkin Studio

PETTWAY BENNETT: When my mother and grandmother was making quilts, you know, when they got a color that was a prize, you know, because it wasn't a whole lot of it. You know, they had to use what they had, and it may have been grays and washed out blues, so when they got a red piece, a dress or pants, that was a prize. And you can just see in the placement of certain colors how it make those quilts popped or stood out.

DUNGY: All of those choices told a story.

PETTWAY BENNETT: My great-aunt, she took all of her husband’s clothing, and it wasn't a whole lot. And when he passed away, she made a quilt from it.

And she said that she made the quilt so whenever she felt lonely for him, she can wrap herself up in it.

DUNGY: The quilts are pretty. But to understand why, it might help to know how they're made.

For starters, the expression is “you piece alone and quilt together.” Piecing is the stitching together of small, well, pieces of usable cloth to make an original design.

PETTWAY BENNETT: The women's pieced the quilt by themself. And this was during the late summer, when they was waiting on the harvest, what we call lay by season. Like, the corn when it dried out or the cotton when it all bloomed out and became cotton. And so they would piece their quilts.

DUNGY: Piecing is about making a design that’s pleasing to your eye, improvising with what you've got. And the women of Gee's Bend have a name for this kind of quilt.

PETTWAY BENNETT: We refer to them as ugly quilts.

DUNGY: Many people make a quilt following a pattern. Traditional designs might include stars or diamonds. In Gee’s Bend, those are known as…

PETTWAY BENNETT: Patterns quilt was the pretty quilts.

Example of a pattern quilt. Linda Diane Bennett (American, 1955–1988). Bricklayer quilt, ca. 1970. Cotton-polyester blend, 80 1/2 x 64 1/2 in. (204.5 x 163.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection, 2014 (2014.548.42) © Estate of Linda Diane Bennett. Photo by Stephen Pitkin/Pitkin Studio

DUNGY: Using a pattern is fine. But it’s not the Gee’s Bend way, and you sense the pride in putting all of yourself into making a quilt no one else could make.

BENDOLPH: Can you imagine sitting there and, the crop didn't come in. You not knowing how you gonna feed your kids or how you gonna make it and you done stuck your finger and now, you bleeding blood and, and you crying and tears falling on your fabric and, it's just a lot because now you're in a place where you can cry those tears. Where you can, you know, thinking about life, why you’re doing it. And it's a place where you can just be. You don’t really have to let anybody in. Just be.

DUNGY: With piecing done, there was a wait before the rest of the quilt was put together…

PETTWAY BENNETT: Winter months after they had did all their harvesting, they would get together like my mother and my grandmother and some of my mom’s aunts. And they would quilt their quilt tops. They will go to this person house until they do all of their top this week.

DUNGY: Each woman would have a number of tops that she'd made. Now, the group would help with the rest, the cotton batting and the backing.

PETTWAY BENNETT: And maybe next week, they'll be to my mom's house. And this is the time that they will gospel, catch up, you know, with what's going on in their lives. They would sew, I mean, sing. They would cook. You know, they would always have a pot of something going on on the stove and so it was a community meeting.

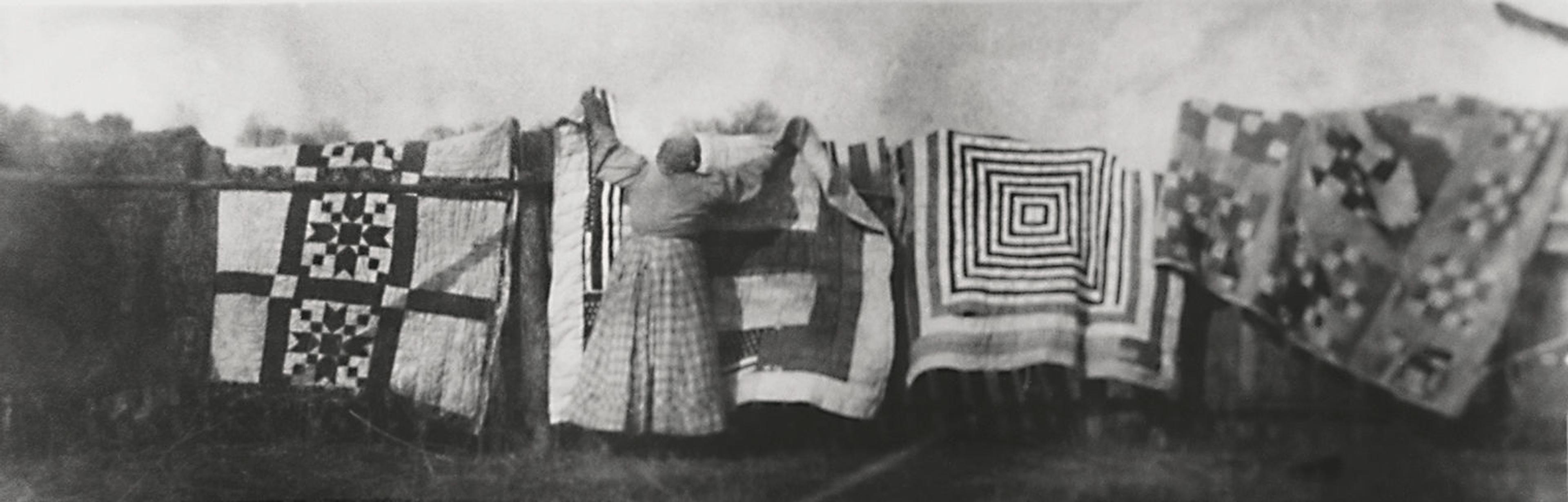

DUNGY: This is when you'd see what other women had made. And in the spring women would air out their quilts, hang them on the line, and the whole town became a gallery of colors and designs, fodder for the next seasons’ inspiration.

Edith Morgan (American, 1875–1939). African American quilts, ca. 1900. Image courtesy Souls Grown Deep Foundation

PETTWAY BENNETT: The neighbors or whoever is walking by, they see that quilt, and they say, oh, I can, I can make that.

DUNGY: This went on for generations. But in the late 1950s, something changed.

PETTWAY BENNETT: When I was in seventh grade, I can remember, my relatives and friends, you know, going to different places, Camden, Selma, marching for equality. When they did Bloody Sunday they was involved in that. My mom was involved more into the schooling part, segregation. And, she got arrested and had to spend the weekend, you know, in jail.

MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. (Voiceover): To come to Gee's Bend and to see you out in large numbers gives me new courage.

DUNGY: In 1965, Martin Luther King Jr. came to Gee's Bend. He urged residents to take the ferry across the river to the county seat, so they could register to vote.

PETTWAY BENNETT: Many of the people over on this side did not have cars or transportation, But they could catch the ferry and they could walk to Camden. And so in order to stop people from going over to register to vote, they stopped the ferry.

The original ferry between Gee's Bend and Camden, ran on cables as shown in the 1939 image by Farm Security Administration photographer Marion Post Wolcott. The ferry was shut down in 1962 by Wilcox County officials as part of the effort to keep African Americans from registering to vote during the civil rights movement. Marion Post Wolcott (American, 1910–1990). Cable ferry from Camden to Gee's Bend, Alabama, 1939. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives

DUNGY: The county sheriff was rumored to have said: “We didn’t close the ferry because they were Black, we closed it because they forgot they were Black.”

Gee's Bend's geography meant that it was suddenly all but cut off. What had already been an isolated community, with few economic opportunities, was now in dire straits. Until someone thought of something Gee's Bend knew how to do all on their own. Something they were good at.

LOUISE WILLIAMS: Our house was a hub.

In the late 1960s, the headquarters of the Freedom Quilting Bee was located in the residence of Estelle Witherspoon, known as “The Quilt House.” Pictured clockwise from bottom left: Annie Nell Square, unknown, Mensie Lee Pettway, unknown, Willie “Ma Willie” Abrams, Jensie Lee Irby, and unknown. Bob Adelman (American, 1931–2016). Quilt House, 1967 © Bob Adelman. Image courtesy Bob Adelman Photo Archive

DUNGY: This is Louise Williams. She grew up in a small town just down the road from Gee's Bend. Her parents were active members of the community, including her mom, Estelle Witherspoon.

WILLIAMS: My mom was one of the people that could read and help people translate documents for those who were older and didn't know how to read and write and things like that.

We need to help teach people to know what the ballot looks like. We need to help people understand who’s on the ballot and how to vote for people and what to say and things like that.

DUNGY: So, when the ferry stopped Estelle heard women in the community start to ask…

WILLIAMS: What can we do? You know, here in this area, what can we do?

DUNGY: Louise's mom quilted, but she was more of an organizer. Still, quilting was in the air, in her blood.

WILLIAMS: My grandmother was born in 1898, and her artistic eye, she could create a pattern from nowhere.

DUNGY: Gee's Bend knew how to make quilts.

WILLIAMS: It probably was about a year of talking and thinking and, and all of that led to it being a sewing cooperative.

DUNGY: The pitch was straightforward.

WILLIAMS: This is not something that somebody has to come in and teach us. This is not something we're doing for free.

This is actually your job, and this is your job here in this community.

DUNGY: They called it the Freedom Quilting Bee Cooperative, and dozens of local women joined. First, they sold their own quilts for a set, stable price. And then, they started to get contracts to custom make quilts and other textiles for big retailers.

WILLIAMS: We had the largest contract with Sears where they would produce, and I can't tell you how many, but it was enough work to keep the ladies, oh, I would say, fifty women or so busy for months on end and for years on end.

And it may not have been a lot of money from the beginning, but it was enough for people to be able to buy food, buy clothes, buy automobiles, buy appliances for their homes.

DUNGY: In the 1970s, that Sears contract asked the women to make patterns that used corduroy…it was the ’70s!…And they brought scraps home to use in their own quilts. If you look at the Gee's Bend quilts that are in the collection of The Met and countless other museums, you see these corduroy scraps.

Quilt by Louise Williams's grandmother, Ma Willie Abrams. Willie “Ma Willie” Abrams (American, 1897–1987). Roman Stripes quilt, ca. 1975. Cotton and cotton-polyester blend, 93 1/4 in. x 70 in. (236.9 x 177.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection, 2014 (2014.548.38) © Willie “Ma Willie” Abrams. Photo by Stephen Pitkin/Pitkin Studio

The Freedom Quilting Bee was a key step in helping the women of Gee's Bend use their skills and artistry to build financial and social stability for themselves for a generation.

Marie Pettway and Lillie Mae Pettway quilting. Bob Adelman (American, 1931–2016). Quilting on porch © Bob Adelman. Image courtesy Bob Adelman Photo Archive

But, by the late 1980s the work had lessened. Textiles manufacturing had moved overseas.

Which made what happened in 2002 all the more surprising.

PETTWAY BENNETT: The first exhibition out in Houston, Texas, of the quilts.

DUNGY: As we mentioned at the beginning of the episode, an art collector had been making regular trips to buy quilts in Gee's Bend. One day the residents were told…

PETTWAY BENNETT: They were gonna be in museums. Uh, of course, none of us believed it.

DUNGY: When Loretta, Louisiana and dozens of other women and families from Gee's Bend got off the chartered buses and stood in the Houston museum gallery, they were in awe of the quilts. Their families’ quilts, lit and hung on white walls.

As she took in these things that were so familiar to her, now totally out of context, she looked to the other people in the space with her. People who were looking intently. Some of those people were in tears.

PETTWAY BENNETT: When people were crying, we at first thought they was feeling sorry for us. I think that, uh, that the women couldn't do any better.

DUNGY: She imagined it must be pity.

PETTWAY BENNETT: They just didn't know how to make any quilt, when we were seeing all this crying, we were thinking that they was feeling so sorry for these poor Black women's in Alabama. They can't make a quilt.

DUNGY: But as she looked again at the quilts, at the people seeing them, she had another thought…

PETTWAY BENNETT: That maybe they were crying because they were beautiful, you know.

[MUSIC]

DUNGY: This was just the beginning. There was another show. And then another, and more. A review in The New York Times called the Gee’s Bend quilts “some of the most miraculous works of modern art America has produced.”

PETTWAY BENNETT: It still took a lot of us time. We still thought they were ugly quilts. But to see other people looking at them and appreciating them. And every time we would go to an exhibition and see this and see people crying. So I started looking through different eyes at the quilts.

And I started seeing what they saw, and when I did see what they saw, you know, it blew me away. It just opened my eyes. It really opened my eyes. I said these are amazing.

DUNGY: And the broadening appreciation just kept growing. In 2006 the quilters of Gee's Bend were featured on The Oprah Winfrey Show. As big a stage as they could imagine.

PETTWAY BENNETT: We all thought it was a dream, but it just kept getting bigger and bigger. And it was like, wow. And the older women's, I was so proud to see the older women's was, getting recognized, and I was so happy for them, to see that they were considered artists even though they themselves did not look at themselves as artists, and we did not treat them as artists.

DUNGY: And then just as the last moment had sunk in, another one…

PETTWAY BENNETT: Oh, when the postage stamp came out, I think, in 2006. Oh, it was, it was like, almost like the Beatles.

DUNGY: In 2006 the United States Postal Service issued a set of 10 stamps featuring the quilts of Gee's Bend. They'd arrived.

PETTWAY BENNETT: People was buying them up. Everywhere I would go, I would try and buy some Gee's Bend quilts stamps. And, they sold out. And I couldn't believe, you know, why?

It really dawned on me, how popular the quilts was, when you couldn't find a stamp.

You know, these women put this together with nothing, and this is art. They look like art. You know? And when people started saying how these are works of art and comparing them to some of the famous artists out there or painters we had never heard of, never thought about.

Because we thought we just, we're just making quilts, we couldn't see no art in them. We just saw necessity and warmth to keeping ourselves warm. It was hard to wrap our heads around it.

And some of us, it's still kinda hard. Myself, I find myself saying, wow.

DUNGY: There were clear upsides to being valued as artists.

PETTWAY BENNETT: Women's got to make money again from their quilts. When they heard the amount they've put on the quilt, they were like, wow. We used to sell these quilts for, like, twenty-five dollars. If you got two or three hundred dollars for a quilt, that was a lot. But now you're talking about three, four, five thousand and up.

DUNGY: In 2013 hundreds of the quilts began to be acquired by museums, including dozens that are now in the permanent collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, where they were first shown in 2018. When Loretta has visited them in museums, she knows exactly who made which stitch, which woman drew her needle across the fabric, as clear as a fingerprint, an artist’s signature.

PETTWAY BENNETT: Some of the quilts that are hanging I slept under those quilts. And now they're considered works of art. You know? And it's just mind blowing.

A quilt has many, many lives. And you think the life of a quilt has started as a plant, weaving it together and may become pants or a shirt or something or a cloth. And it takes on another life for being, turned into a quilt. Or maybe after being worn out or worn to nothing or just about it, and then it turned into something else, a towel or a curtain or rug on the floor. And it tells stories, a quilt. Like, many, many lives.

[MUSIC]

—

DUNGY: Immaterial is produced by The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Magnificent Noise.

Our production staff includes Salman Ahad Khan, Ann Collins, Samantha Henig, Eric Nuzum, Emma Vecchione, Sarah Wambold, and Jamie York.

Additional staff includes Julia Bordelon, Skyla Choi, Maria Kozanecka, and Rachel Smith.

This season would not be possible without Andrea Bayer, Inka Drögemüller, and Douglas Hegley.

Sound design by Ariana Martinez and Kristin Mueller.

This episode includes original music composed by Austin Fisher.

Fact-checking by Mary Mathis and Claire Hyman.

Sensitivity listening by Adwoa Gyimyah-Brempong.

Immaterial is made possible by Dasha Zhukova Niarchos. Additional support is provided by the Zodiac Fund.

This episode would not have been possible without Alexandra Barlow, Marie Watt, Loretta Pettway Bennett, Louisiana Bendolph, and Louise Williams.

And special thanks to Eva Labson, Scott Browning, Curator Amelia Peck, and Avery Trufelman.

To see images of the artworks featured in this episode, visit The Met’s website at metmuseum.org/immaterialblankets.

I’m your host, Camille Dungy.

###