Read the show notes and illustrated transcript below.

Listen and subscribe to Immaterial on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube, Pandora, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Show Notes

Linen often evokes an image of luxury. From the tombs of Egyptian rulers to the palaces of India, from the bedrooms of French chateaus to boardrooms of Wall Street, the opulence of linen communicates wealth.

The episode begins with a 3,500-year-old piece of linen found in the tomb of a woman named Hatnefer—mother to the architect for King Hatshepsut. Curator Emerita Catharine Roehrig describes it as “a delicate little cloud,” made from one of the most expensive types of linen. Weighing almost nothing, this magical cloth was placed in Hatnefer’s tomb for her use in the afterlife.

But as much as linen is recognized for its elegance, it is also marked by its capacity to oppress. In the nineteenth century, textile companies located in states like New York and Massachusetts—Brooks Brothers among them—manufactured linen and wool uniforms for enslaved and formerly enslaved people who served in roles like butlers, drivers, and doormen. Dr. Jonathan Square, a professor and research fellow in The Met’s Costume Institute, connects the many facets of linen—the coarse and durable, with the fine and affluent. In a runaway slave ad that details an extensive list of clothing that the freedom seeker took with him, including a red linen jacket and linen shirt and trousers, Square remarks that such garments would, like magic, transform the enslaved man into a free man both in fact and in the eyes of the people who saw him.

Tracing the path of linen in garments from ancient Egypt to the present day, we also meet fashion historian Rachel Tashjian, who explains the impact of linen in Giorgio Armani’s designs on popular culture. And finally, Cora Harrington, “The Lingerie Addict,” blends her study of history, sociology, culture, and economics to reflect on the unseen importance of linen undergarments. Necessary for hygiene—as it separated the body from layers of costly clothing they wore each day—corsets, drawers, and more made linen an essential item in the day-to-day lives of nineteenth-century women.

Listen for the whole story, and scroll through the gallery below to take a closer look at the art mentioned in the episode and some highlights made from linen in The Met collection.

Transcript

CAMILLE DUNGY: If you could bring something with you into the afterlife, what would it be?

A miniature replica of your beloved cat? A cherished ring? A love letter? What about a sheet of linen woven with superfine thread and big enough to cover a table for you and fifteen of your closest friends?

CATHARINE ROEHRIG: It’s incredibly sheer and it would have been one of the most expensive kinds of linen.

DUNGY: This is Catharine Roehrig, curator emerita of Egyptian Art at The Met. She spent over thirty years studying and interpreting the collection, which includes more than nine hundred linen-related pieces.

ROEHRIG: I was looking in that case with one of the textile conservators who was the head of the department, Nobuko Kajitani, and she put it in my hands, and it weighed nothing. She called it “a little cloud.” So it was like holding a little cloud in your hands.

DUNGY: The “little cloud” she’s talking about is a 3,500-year-old piece of linen cloth that was found among many more in the tomb of a woman named Hatnefer, who lived in ancient Egypt.

ROEHRIG: She just happened to have a lot of boxes of linen that were buried with her. And every one of those pieces of linen was folded very carefully, so that when it was put in the box it looked like it was perfect. And Egyptians believed in magic. So when you fold a sheet and make it look perfect, then essentially it is perfect for the afterlife.

DUNGY: This particular piece of fabric is “royal linen,” believed to have been a gift to Hatnefer from Egypt’s ruler. Catharine says that by the time she died in her late seventies, Hatnefer would have been considered a “grand old lady.” And she was pretty well known because her son was the architect for Queen Hatshepsut.

ROEHRIG: Actually she’s a king. Hatshepsut was the longest reigning female ruler of Egypt. And she ruled basically as king because in Egypt you don’t have a word for queen. You have a word for “King’s wife.” So, in fact, you should actually call her a king.

DUNGY: And a gift of linen from the King was a high honor. But whether you had royal linen or everyday linen, nearly everyone in Egypt relied on the textile.

ROEHRIG: It’s the fabric that’s used to do almost anything you would do with fabric. So, it was something that was valuable enough that you used it and used it and used it and used it.

DUNGY: You used it to make clothes, mattresses, chair cushions, sails, and, eventually, when all of that was worn through, the same linen could be used to wrap the mummy of a loved one. Or, as happened with Hatnefer’s linen, it might be stored along with them so they could use it again in the afterlife.

Linen is created from the flax plant, whose Latin name translates to “most or very useful,” and that’s because it’s incredibly durable. A person could use the same piece of linen their entire life, and that same linen can still exist, more than 3,000 years later in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The fabric seems to last forever.

ROEHRIG: That is the impression one gets. [laughs] And it seems like it should be something that’s fragile because it’s made of plants, but Egypt is a perfect place for preservation. Linen being in a dry circumstance is really very well-preserved even after thousands of years.

DUNGY: One more thing that makes linen valuable is that it’s so labor-intensive to make. Inside the thin stem of a flax plant are cellulose fibers that, when removed, can be transformed into a durable, versatile textile. Even today, linen can be left nearly as rough and coarse as the plied, twisted fibers that can be so hard on weavers’ hands. Or it can be worked and worked until it is as light and lovely as the “little cloud” of cloth in Hatnefer’s tomb. And Catherine says it’s important to note that in ancient Egypt, it was likely women who did the work of spinning and weaving flax into the most important material in the land.

ROEHRIG: Egypt has more records of women than most ancient cultures, because they’re actually represented in scenes of daily life. We excavated a model that’s now in Cairo of women weaving. Images of women spinning, images of women doing weaving, indicates that it’s probably something women would do. And it’s something they could do in the courtyard of a house. It’s something they could do while taking care of children, because you can weave while the kids are asleep, you can spin while the kids are asleep or running around you.

DUNGY: What does it mean when we put linen on our bodies now?

Whether worn as outerwear or underwear, linen garments have evolved and so have their meaning. It is a luxurious, expensive material, one of status and wealth, but its potential coarseness and its history also have the capacity to oppress.

No material is neutral, and linen is no different.

From The Metropolitan Museum of Art, I’m Camille Dungy, and this is Immaterial, where we look at materials commonly used in making art and explore what the materials themselves can tell us. This episode: linen.

—

DUNGY: In the 1980s, one Italian designer’s use of linen became a shorthand for wealth, Wall Street, and the red carpet.

Giorgio Armani founded his fashion house in 1975. By 1980, he had become what fashion critic Rachel Tashjian calls, “the defining Hollywood designer.”

RACHEL TASHJIAN: Both on screen, working with Richard Gere and Martin Scorsese, but also just dressing people on the red carpet, you know, no one had really done that. And he became the guy who was like, ‘God,’ you know, ‘you all look terrible. Why don’t you wear Armani?’ [laughs]

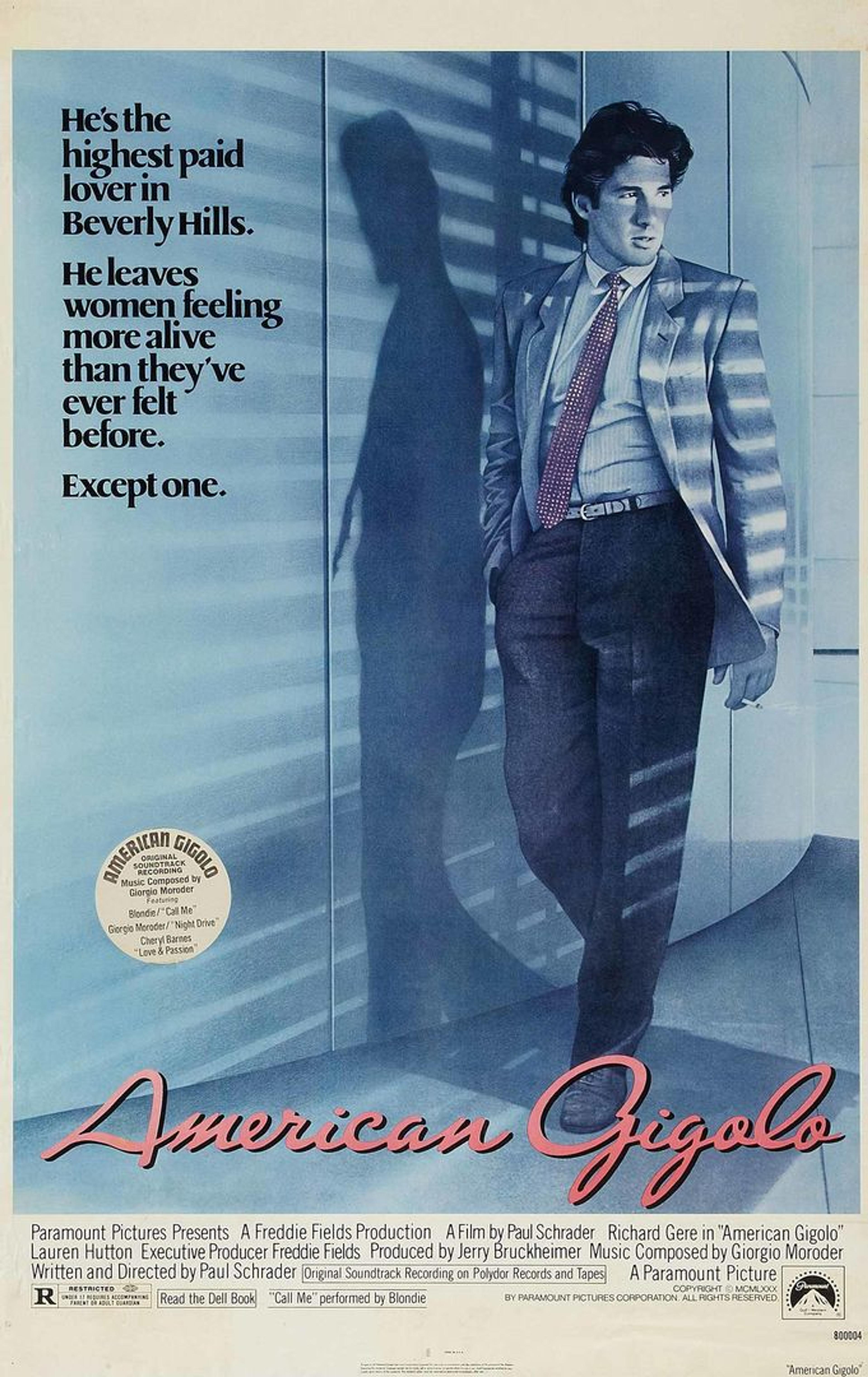

DUNGY: When Rachel references Richard Gere, she’s talking about a movie that was a huge hit in early 1980: American Gigolo.

[American Gigolo clip begins]

It starred thirty-year-old Gere as the ultimate high-priced, irresistible, Hollywood sexy man. Wearing, of course, Armani.

[American Gigolo clip where you hear Gere singing along to “The Love I Saw In You Was Just A Mirage” by Smokey Robinson & The Miracles]

A poster for the movie shows Gere leaning against a wall as he angles his body toward the camera. Slats from partially open blinds throw light and shadow across his face and across the relaxed, almost-floppy, tossed-open jacket of his expensive—but casual—linen suit.

AMERICAN GIGOLO, Richard Gere, 1980. © Paramount Pictures / Courtesy: Everett Collection

TASHJIAN: I think it has this really singular ability to represent luxury and humility at the same time. Inherent to that is the kind of elegance that this fabric just creates with its natural sort of movement. I’m thinking of in particular this wobbly quality that… I have a lot of vintage Armani pants that I’ve bought for my boyfriend and they always have this kind of slight Jell-O quality to them when they’re moving that’s so beautiful.

DUNGY: One scene in American Gigolo follows Gere around his spacious apartment. Wearing softly tailored trousers and no shirt, he opens his closet to reveal a row of stylish jackets, some of which he selects and lays gently on his bed. He opens a drawer and lets his fingers run across the fabric of several linen shirts. For more than two minutes, the scene revels in the sensuality of the clothes this beautiful, sculpted man is about to put on his body.

It’s a display of a kind of effortless luxury that linen clothing has come to represent. It signals wealth whether you actually have it, or not.

TASHJIAN: I have this image too, when we talk about linen, of like, this just like really tanned guy with his Rolex and, like, his rolled up linen shirt, I don’t have an image like that for any other fabric.

DUNGY: There’s something about this way of wearing linen that feels prototypical of a certain kind of wealth… and perhaps whiteness. A way of being in the world.

TASHJIAN: There’s some pretty, intriguing images, for example, of Prince Charles in the 1980s on a number of Royal tours with Diana. And he often is wearing these, kind of, linen shirts and safari shirts.

DUNGY: The uniform of colonial power. And keep in mind, this was in the 1980s, the height of “Greed Is Good” capitalism, Reagan, Wall Street, and the Giorgio Armani suit.

TASHJIAN: I think it can be difficult to wrap your head around how revolutionary Armani was. But what Armani did starting in the late seventies—like, probably around 1978 would have been when he first really came to public attention—was he tore out all of the, sort of, stuffing and padding that exists in men’s suiting. So, no shoulder padding, no lining, you know, you would open the jacket and you would just see the other side of the fabric—which was very often linen, sometimes wool—in the pursuit of this very naturalistic, kind of earthbound way of making clothing. It was very much about honesty, sincerity, a kind of sense of connection with oneself, a sense of modesty.

DUNGY: But Armani’s loudest wearers were often anything but modest.

TASHJIAN: For some reason it became like this ultimate name-drop in the 1980s. Basquiat bragged about wearing Armani suits just as much as, like, Gordon Gecko did, you know? The consistency of, like, the omnipresence of Armani as just this, like, ‘this means power.’

DUNGY: Rachel says that fashion critics like Judith Thurman suggest that, as opposed to showing off their wearer’s power, perhaps these suits were the 1980s version of the emperor’s new clothes: chance to show off, at any cost.

TASHJIAN: She began to see Armani as the perfect cocoon or uniform for someone who’s deeply insecure.

DUNGY: How did what Rachel calls “easy Mediterranean, California feel good clothing for the wealthy” become a uniform for men on Wall Street? Rachel has a theory about why designers and brands like Armani, Ralph Lauren, and Brooks Brothers chose linen for their high-end designs. It connects to ancient Egypt, a time when kings also prized linen.

TASHJIAN: If you think about a designer like Armani, who was one of the, I think, the defining designers to really position linen as this luxury material, I do think it comes from this sense of history that linen has, it’s something that can be traced back to Egyptian culture. It’s also, of course, something that is associated with the Mediterranean world with the quote-unquote “cradle of civilization.” That’s very exciting to think about, the idea of fashion that connects a designer to the very beginnings of modern civilization.

Whereas I think, to contrast it with cotton, I think that cotton is a material that we’re only beginning to really come to terms with its really troubling place in the history of the world and, of course, you know, in capitalism itself. But if you think about linen, as opposed to cotton, linen has a sort of mystique to it and a history that I think fashion designers are proud and excited to associate themselves with.

DUNGY: But when it comes to the idea of using linen because of its supposed pristine and uncomplicated past, these designers were quite simply… wrong. More on that, after the break.

—

DUNGY: Dr. Jonathan Square has always been a lover of art, fashion, and creative expression. He’s a professor of Black visual culture at The Parsons School of Design and a Fellow at The Met’s Costume Institute.

JONATHAN SQUARE: Was that too formal? Should I just be like, I’m a dude who lives in Brooklyn and... [laughs]

DUNGY: Jonathan grew up in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. From an early age, he noticed how people like his grandfather, who worked as a mason, got dressed.

SQUARE: His look was the Dickies coverall, a paisley handkerchief, and, like, a white ribbed tank top.

DUNGY: A look that’s now become a go-to classic for Jonathan.

SQUARE: Because it makes me feel like a superhero. It’s like a single outfit that you sort of slip into. So, it makes me feel stronger, confident, ready to take on the world.

DUNGY: Jonathan brings his aesthetic eye to his study of clothing both worn and created by enslaved people.

SQUARE: This is very personal to me, because I’ve always been an aesthete. Both my parents were artists and they met in art school. And also, like, I’m a Black southerner, like, I’m a descendant of enslaved people. My interest in slavery is academic. But it’s also a personal interest, as well, because it’s tied to just like my existence in the world. And so, at some point, I decided to marry those two interests.

DUNGY: He’s interested in the sometimes blurry lines between the functionality of workwear and the ways enslaved people took what they were given and created their own expression of style.

SQUARE: You know, when people think about slavery, they don’t necessarily think about how enslaved people were made to dress. But I think it’s a really important, sort of, entry point to thinking about the experience of enslaved peoples. And linen is a part of that. And I know now we think of linen as being sort of a light breezy, carefree textile, but many enslaved peoples’ clothes were actually made out of linen.

DUNGY: For his research, Jonathan uses a database of nineteenth-century advertisements written by enslavers, which have been cataloged and digitized and are searchable by keywords. This is how he learned about Alexander Lucas.

SQUARE: I know very little about him beyond what’s written in the runaway slave ad. And that ad really stuck out to me because of the multiple references to linen.

DUNGY: When researching my own book, Suck on the Marrow, I also ran across ads like these. They described identifying features like scars or missing teeth, things the freedom seekers may be carrying, and the color and patterns of what they might be wearing.

Here’s Jonathan reading the extensive list of clothing that Alexander Lucas was said to have left with.

SQUARE: “The clothes he took away are such as people of his condition do not generally wear. He absconded with a new course green coat, spatter with red and white intermix; a new red striped linen coat; a jacket nearly the same with backs of planes and the old coarse linen, ditto.”

DUNGY: Ditto meant, ‘same as what has already been mentioned.’ So Alexander Lucas ran away with a new green coat, a new red coat, a new red linen jacket, and an old, coarse linen jacket. The ad went on to list several pairs of short trousers, a new white linen shirt, black leather stockings, buckled shoes, and a knapsack.

SQUARE: Funny enough, it’s actually not that unusual of an ad. I mean, I was really struck by this ad because of the many references to linen, but in terms of its length it’s not unusual. There’s often, like, lengthy descriptions of the clothing that enslaved people took with them.

DUNGY: In the nineteenth century clothing could serve as a form of currency. This was true in ancient Egypt, too, where linen cloth could be traded for barley. In Alexander Lucas’s era, clothes were incredibly expensive to make. Garments could sell for twenty, forty, sometimes sixty dollars—that’s the equivalent of hundreds of dollars today. So when enslaved people ran away, they not only took their own clothing with them, often they took the clothing of their enslavers—to trade for food, safe passage, and lodging.

SQUARE: Also, what I find interesting about the ad is that there’s often descriptions of the enslaved person’s personality. And I think it reveals one of the contradictions of slavery because to slave someone, you have to think of them as being less than human, but when they run away, you have to describe them as being a human being. And it can’t be, you know, ‘they’re a Black person and they’re this height and,’ you know, ‘they had on a red shirt.’

DUNGY: One thing this reveals is how intimately enslavers knew the people who labored for and around them.

SQUARE: It had to be very specific, you want to identify the enslaved person that ran away. So you have to give really detailed information about the way they smile, the way they laugh, their personality, the kind of accent that they have. So you’re sort of reinforcing their humanity while trying to take away their humanity.

DUNGY: We learn a lot about what kind of person Alexander Lucas was from this ad.

SQUARE: I’m pretty clear based on the clothing that he took with him that he wanted to pass as a free person. Like, he needed a more extensive wardrobe and so he took an extensive wardrobe with him to sort of look like someone who was free. Also, you know, looking at the clothing that he took, you can see that fashion and adornment was important to him. When you leave some place, especially a place that, you know, that you might not be coming back to, you take what’s most important to you. And he took a lot of clothing with him because clothing was important to his identity.

DUNGY: Heading into the unknown, even a necessary unknown, can be terrifying. Sometimes it helps to wrap yourself in fabric of protection. Like the Egyptian Hatnefer, who took her precious royal linen with her into the afterlife, Alexander Lucas took coats, jackets, and breeches to aid his passage into a new life.

There is also something huge here about how we create our images in the eyes of others based on the visual cues we send. Alexander Lucas found the right clothes and he stole himself away. He transformed himself into a free man, both in fact and in the eyes of the people who saw him. What an astonishing piece of magic to have achieved with linen.

[Ambient music, paper tearing]

DUNGY: But remember, not all linen is the cloud-like texture of Hatnefer’s cloth or Prince Charles’s safari shirts. Alexander Lucas had coarse linen coats as well as new ones. He had to choose the clothing he took with him wisely if he wanted to look like somebody legally entitled to determine where he took his own body.

SQUARE: Many enslaved people received what is often referred to as ‘Negro cloth,’ textiles that are manufactured specifically for enslaved people. Negro cloth was rough and uncomfortable, but it was also durable, which is great for workwear.

DUNGY: The creation of fabric and clothing made specifically for enslaved people was an entire industry. There were some factories in the South but the industry was largely based in the Northeast: states like New York, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and Connecticut. Jonathan points out that Brooks Brothers—one of the companies selling linen suits to Wall Street elites right alongside Armani—benefited directly from the institution of slavery by creating uniforms. Brooks Brothers designed these linen and wool uniforms for enslaved and formerly enslaved people who served in roles like butlers, drivers, and doormen.

But some enslaved people received ready-made garments that were often just basic shifts. In eighteenth- and nineteenth-century archives, I’ve often seen ‘Negro cloth’ referred to as ‘slave cloth.’ It was cheap, plain, unbleached, and rough.

SQUARE: Booker T. Washington, in his book Up From Slavery, which recounts his childhood as an enslaved boy, he talks about a shirt that was so uncomfortable that his older brother, Wharf, wore it first, broke it in, and then gave it to him.

DUNGY: Other times, enslaved people would receive bolts of this linen fabric and be responsible for hand-sewing their own garments. This was the case for a woman named Harriet Jacobs.

SQUARE: Harriet Jacobs talks about this “linsey-woolsey” dress that she was made to wear as an enslaved girl. Like, ‘linsey-woolsey’ is a linen-wool mix. Clearly you have a very uncomfortable textile, a very uncomfortable dress to wear. So, when she thinks about that badge of slavery, it’s that dress, which was made out of linen and wool, which I think is really interesting.

DUNGY: Harriet Jacobs is typically recognized for her abolitionist work, but we know that she was also a skilled seamstress. She learned to sew when she was a child, from her enslaver. She sewed coarse, linen clothes for other enslaved people. And then, at the age of twenty-two, she freed herself. The ad placed by her enslaver even mentioned her sewing skills, and for the next seven years, Jacobs hid in her grandmother’s attic, sewing and reading the Bible by candlelight. Jonathan writes that “her legacy as a fashion creator lives on through her writing and the abolitionist efforts that her sewing enabled.”

Note that Jonathan used the term ‘fashion creator’ rather than fashion designer. The term ‘designer,’ he says, is political.

SQUARE: When we think about designer, when we think about the twentieth and twenty-first century, and we often—except for Coco Chanel and maybe Schiaparelli—we think of, like, white men. Yves St Laurent, Balenciaga, Christian Dior, even someone like Halston or Tom Ford or Marc Jacobs. We associate designers with, like, intellectual labor, conceptual work. Many of these men can actually sew and know how to construct the garment, but some of them don’t [laughs]. They sketch, they tell other people what to do. And I think one of the things I wanted to do in this work is just to reveal, like, the intellectual labor of fashion-making that Black women were involved in in the eighteenth and nineteenth century.

DUNGY: Jonathan’s work highlights this invisible labor. These women’s creations may show up in museums without credit if they show up in museums at all.

SQUARE: In most museums, there’s a heavy focus on high fashion. And for that very reason, few enslaved people and formerly enslaved people had access to high fashion. And so that’s one reason there’s often less of a focus on utilitarian, like, work-a-day clothing.

DUNGY: Jonathan says that when you do see utilitarian clothing in museum collections, it’s often from a person who worked in the household of a wealthy family.

One rare example is in The Historic New Orleans Collection. It’s a Brooks Brothers wool livery coat dating from the 1850s or 60s. Jonathan believes the coat was purchased in New York City and transported to New Orleans for use by a young male domestic laborer enslaved in the household of the president of a local bank. I first heard about this coat from a friend after she saw it at the museum. She told me she could not stop staring at the big silver buttons. They were embellished with the crest of the wealthy family, to announce who the uniform, and the person who wore it, belonged to.

SQUARE: Think about how museums are collecting now. They’re not collecting Crocs, or Telfar bags, or clothing from Target. They’re collecting designer, clothing, high-fashion, couture clothing. And so it’s happening as we speak. But you know, a hundred years from now, someone is going to want to see a Telfar bag, or a pair of Crocs, or a pair of flip flops, or the things that we consider, like, cheap or not worth saving.

DUNGY: Linen maintains its high value when taken from a mummy’s tomb, or when it’s in the form of an Armani suit, or even when it’s woven into the uniform for a domestic laborer in an elite person’s household. Value accompanies power. Museums today rely on what people from the past decided was worth caring for and keeping. Which made me wonder whether Jonathan had come across anything directly connected to his studies in The Met’s Costume Institute.

SQUARE: Nope. That was my first question. I was like, ‘first off before we do anything else, has there been anything identified in the collection that was created or worn by an enslaved person?’ And they were like, ‘not that we know of.’

Honestly, I think there’s something, you know what I mean? Like their collection is so vast that it’s hard for me to believe that there’s nothing in the collection that wasn’t created or worn by an enslaved person, but there’s no documentation to prove it. Actually, it’s something, it’s one of my goals during the fellowship is to identify something.

DUNGY: The historian Kellie Carter Jackson once said that the abolitionist movement was a form of protest and disruption of capitalism. You stole yourself and others away from enslavers, and gave yourself back to yourself, claiming the value of your life, body, and labor as your own. As Alexander Lucas’s story revealed, you might also take your enslavers’ clothing and their emancipated identity along with you. We transform our bodies in the eyes of those who see us, which of course is one massive point of clothing.

But what about garments that aren’t necessarily intended for the public to see?

CORA HARRINGTON: What you’re seeing when you see lingerie is people’s inner most lives. It’s not just intimate apparel because it’s worn at home, or it’s because of sex, or something like that. It’s intimate because it’s worn directly against the skin. And you’re able to learn things from that that you can’t get from other garments.

DUNGY: Cora Harrington is known professionally as “The Lingerie Addict.” She started a blog in 2008 initially as a means of reviewing bras, underwear, and other intimates. Now, Cora blends her study of history, sociology, culture, and economics to discuss the fashion industry, identity, and how lingerie can be understood as an extension of ourselves.

And linen is a part of all that.

HARRINGTON: The word lingerie is derived from the French word for linen. And it’s one of those words that carries over into modern English. It’s interesting to me, in that we don’t really wear linen lingerie so much anymore. You could find linen lingerie if you search for it, but it’s not easily accessible. But that word, that connotation of linen is still present today in the word for lingerie and how we talk about it.

DUNGY: Let’s go back to a time when undergarments were primarily made out of linen. The Met’s Costume Institute holds many of these Victorian-era pieces. Like French men’s underpants from the 1830s that look less like cotton Hanes briefs and more like an exquisitely tailored pair of linen trousers—with adjustable laces to cinch the high waist and draped fabric down the legs. There’s also an American linen lingerie set from 1898 that consists of three floor-length, generous women’s garments with ruffles, intricate pleating, and lace trim.

HARRINGTON: One thing I do think is worth unpacking about underwear or about lingerie is the idea that it’s inherently sexy. Particularly when you’re looking at linen drawers from the nineteenth century for people like Queen Victoria, which are distinctly unsexy in my opinion.

DUNGY: There some of these loose-fitting waist garments in The Met collection. Pieces like these can tell us a lot about the values of the culture from which they come and that culture’s attitudes about things like sex, gender, and respectability.

HARRINGTON: A really good anecdote for how Victorian people would have thought of lingerie at that time is that, when you look at Victorian underpinnings, you know. the big drawers. And they’re called a pair of drawers, because like it’s two different ones that are like sewn together, which is why it’s plural instead of, like, ‘a drawer.’

DUNGY: These linen drawers often looked like a mix between an apron and a floppy pair of shorts.

HARRINGTON: Wide open in the middle, they’re open crotch knickers. And, like, today that’s considered a very sexy thing, but in the past that would have been considered a modest thing because you weren’t pulling up all these layers of skirts to use the bathroom, right? Like, it was split to make it more convenient to use the restroom.

DUNGY: Flushing toilets as we think of them today didn’t become common fixtures until the early twentieth century, so it makes sense why it would be useful for underwear to be constructed like that.

HARRINGTON: But also if you saw someone with closed drawers, that implied that they were a sex worker. Because if your drawers were closed, that meant you had to take them off to do anything. And so, I think that’s a good example of Victorian social mores for that era, but then also how they differ from our modern perspectives.

DUNGY: This kind of thing comes up in Cora’s line of work… a lot.

HARRINGTON: I just retweeted a post from, like, a Victorian Twitter account that was like, ‘oh, look at this romantic couple from the Victorian era.’ And I was like, ‘that’s pornography!’

This is porn, friends. https://t.co/OjPVb8bdlE

— Cora Harrington (@lingerie_addict) November 15, 2021

DUNGY: I know what you might be picturing, but remember, this is from the late-1800s. In the image, a man and woman are seated together in what looks like a parlor—the room is not a parlor. To our contemporary eye, there appears to be a lot of linen fabric covering the woman’s body.

HARRINGTON: Like, she looks fully dressed to us today, but she was in her underclothes sitting on this man’s lap and I’m like, ‘that’s not… that’s not a romantic photo, you guys. Like, that’s definitely porn.’ [laughs] So kind of going back to this idea of, like, what we see when we see a photo from 1895, versus what someone in 1895 would’ve seen without that added context. But the context is, like, this was porn.

DUNGY: Cora says we may also be mis-applying modern-day perspective on lingerie when we think about corsets. The Met has some linen corsets dating as far back as the early eighteenth century. What comes to mind when you think of a corset? Maybe you’re thinking of silk corsets. Intricate pieces worn by women who lace one another tightly in Gone With The Wind. Or even something campy and contemporary like the corsets worn in Rocky Horror Picture Show. Cora says there’s been a modern corsetry renaissance where makers rediscovered old patterns, while seeking to upend a lot of the old stereotypes.

HARRINGTON: A popular one is everybody wore tight lacing, and nobody could breathe, and there were fainting couches all over the place, and you only wore corsets if you were a very, very wealthy woman, and people were lacing their waist to sixteen inches and, you know, tipping over all the time.

DUNGY: I’ll admit that my image of a corseted woman was a lady of leisure who was able to make frequent use of a velvet fainting couch. But Cora corrected me.

HARRINGTON: And when you actually think about it, it makes absolutely no sense whatsoever. Tight lacing, just like it is now, was a very kind of specific, specialized, fetishistic in some cases, practice. I mean, we also have to remember that the era in which corsets were being worn every day, it was also the era prior to bras. And so if you want it bust support, back support, scaffolding for all these heavy layers of dresses you were wearing on top, the corset was what you wore. And I think there can be a tendency to apply our modern day standards of comfort and beauty and liberation to what people were wearing in the past without thinking that, okay, you’re a maid in a lady’s house and you’re working sixteen hour days. You’re going up and down stairs, carrying buckets of coal, carrying buckets of water, going to the market, carrying baskets of vegetables, fairly intensive physical strenuous work. That corset has given you bust and back support.

DUNGY: Hearing this story from Cora changed my entire conception of corsets. Now I can see how linen would be an ideal fabric for lingerie and other underwear. It can be cool and breathable. As you sweated, the fabric would absorb the moisture and form a sort of air conditioning close to your skin. While in colder weather, it could insulate your core. The fact that linen is so durable would mean that you could keep a linen undergarment longer than you might be able to maintain something made from a more delicate textile.

HARRINGTON: Linen could hold up to very harsh cleaning. So, you could put linen in boiling hot water, or, like, bleach it, or put it in the sun and it would be fine. And you can’t, you couldn’t say that for a silk velvet or, like, a wool, necessarily, but linen could take a beating. And it was also breathable, it was light. You could, um, it had some kind of, like, antifungal, antibacterial properties, it wicked moisture very easily.

DUNGY: All of these things sound pretty great for fabric people wore so close to the body.

HARRINGTON: It was a lot more difficult to wash your outerwear and some pieces couldn’t really be washed. Then your linen would protect what you wore on top of it.

DUNGY: You wanted to protect those outer clothes because, like Jonathan made clear earlier, they were extremely expensive. The worth of clothing—and by extension, the worth of the labor that went into making it—has an even greater expense than its impact on your pocketbook.

HARRINGTON: Clothing is cheaper now than it’s ever been in all of human history. And I think it’s very difficult for people today to cognate, not just how long things took to make, but how expensive things would have been.

DUNGY: Cora shared the story of King Charles I, who in the year 1632 was said to have spent more than two thousand pounds per year on lace and fine linen. That’s equivalent to about $345,000 today.

HARRINGTON: Or, if we’re talking about, like, people’s labor, 30,000 days of labor by skilled tradesmen. And that was just like one year’s worth of lace and linen that he bought.

DUNGY: The king’s extravagant spending led to a public outcry. But Cora reminds us that the people working in the homes of the wealthy would often be paid in clothing because of its high value. A kind of example of trickle down economics, I guess.

HARRINGTON: When we look at employment contracts of the past and people like servants are getting paid and underwear and changes of clothes, like, that is why. Like, keeping in mind they should have been paying servants more, obviously. But paying people in clothing sounds very, very strange to us when you can buy a t-shirt for five dollars. But at a time when clothing would have been among the most expensive things you owned, to the point that people would pass clothing down in wills and use it until it became literal rags, and those rags would go on to make paper. Like, that helps, I think, to, to adjust our perspective of, like, the value of clothing and, additionally, how much we are in some ways, like, underpaying for the value of that labor today.

DUNGY: Cora talks with great reverence about some of the nineteenth-century hand-sewn pieces she’s seen. Luxuries like bridal garments, stitched of linen, lace, and silk by working class people.

HARRINGTON: A friend of mine gave me his grandmother’s, or great-grandmother’s wedding day set. Her wedding gown that she made herself, I think from like 1908, her corset that she made herself, her undergarments that she made herself, like, with her own embroidery, all of that.

Every once in a while I pull out the pieces and look at them and they’re simple. It’s not like I’m looking at, like, a royal wedding suite. But they’re very clearly made by someone who knew what she was doing, and it was made with love, like, all the embroidery on it is hand-done.

DUNGY: Contemporary versions of such hand-sewn dresses would cost many thousands of dollars today.

HARRINGTON: I think it’s an incredible connection to the past—not my personal past ’cause, like, I’m Black, like, the situation of my family in 1908 was not the same situation of his family—but I think, like, the larger textile and clothing story, it’s a part of that conversation, which is fascinating to me.

[Soft, humming music]

DUNGY: The fact that a relatively large sheet of linen fabric was buried in Hatnefer’s tomb is one of the ways that we know she died as a woman of high standing. For another family in ancient Egypt, such a valuable length of fabric would have been passed along for the next generation to use.

I continue to think about the legacies we know, and those we don’t. I picture the flax plant, growing to sometimes over three feet in fertile soil, filling fields with blue flowers. I picture it spun and then woven into linen fabric, left rough and stiff, or worked until it’s breezy and soft and highly valued.

Where it settles is, in large part, the result of the labor of people who weave it, the values of the people who buy it, the history of the people who wear it, and the choices of the people who save it. And perhaps, pass it along.

—

DUNGY: I’m Camille Dungy, and this is Immaterial.

Immaterial is produced by The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Magnificent Noise.

This episode was produced by Eleanor Kagan.

Our production staff also includes Jesse Baker, Eric Nuzum, Adwoa Gyimah-Brempong, and Elyse Blennerhassett.

And from The Metropolitan Museum: Sarah Wambold, Benjamin Korman, Rachel Smith, and Douglas Hegley. This season would not be possible without Sofie Andersen.

Sound design by Ariana Martinez. Mixing by Ariana Martinez and Kristin Mueller.

This episode includes original music composed by Austin Fisher.

Fact-checking by Christine Baird.

The podcast is made possible by Dasha Zhukova Niarchos.

Additional support is provided by Bloomberg Philanthropies.

This episode would not have been possible without: Catharine Roehrig, Curator Emerita in Egyptian Art; Emilia Cortes, Conservator in Textile Conservation; Jonathan Michael Square, The Gerald and Mary Ellen Ritter Memorial Fund Fellow at The Costume Institute; Jessica Regan, Associate Curator at The Costume Institute; Mellissa Huber, Assistant Curator at The Costume Institute; Janina Poskrobko, Conservator in Charge in Textile Conservation; Cristina Carr, Conservator and Coordinating Conservator for the Antonio Ratti Textile Center in Textile Conservation; Kristine Kamiya, Conservator in Textile Conservation; and Minsun Hwang, Conservator in Textile Conservation.

And special thanks to Dr. Vanessa Holden, Associate Professor of History and African American and Africana Studies and the Director of the Central Kentucky Slavery Initiative.

To see linen corsets, drawers, Armani suits, and that 3,500 year old “little cloud” from Egypt, visit The Met’s website at metmuseum.org.

I’m Camille Dungy.

###