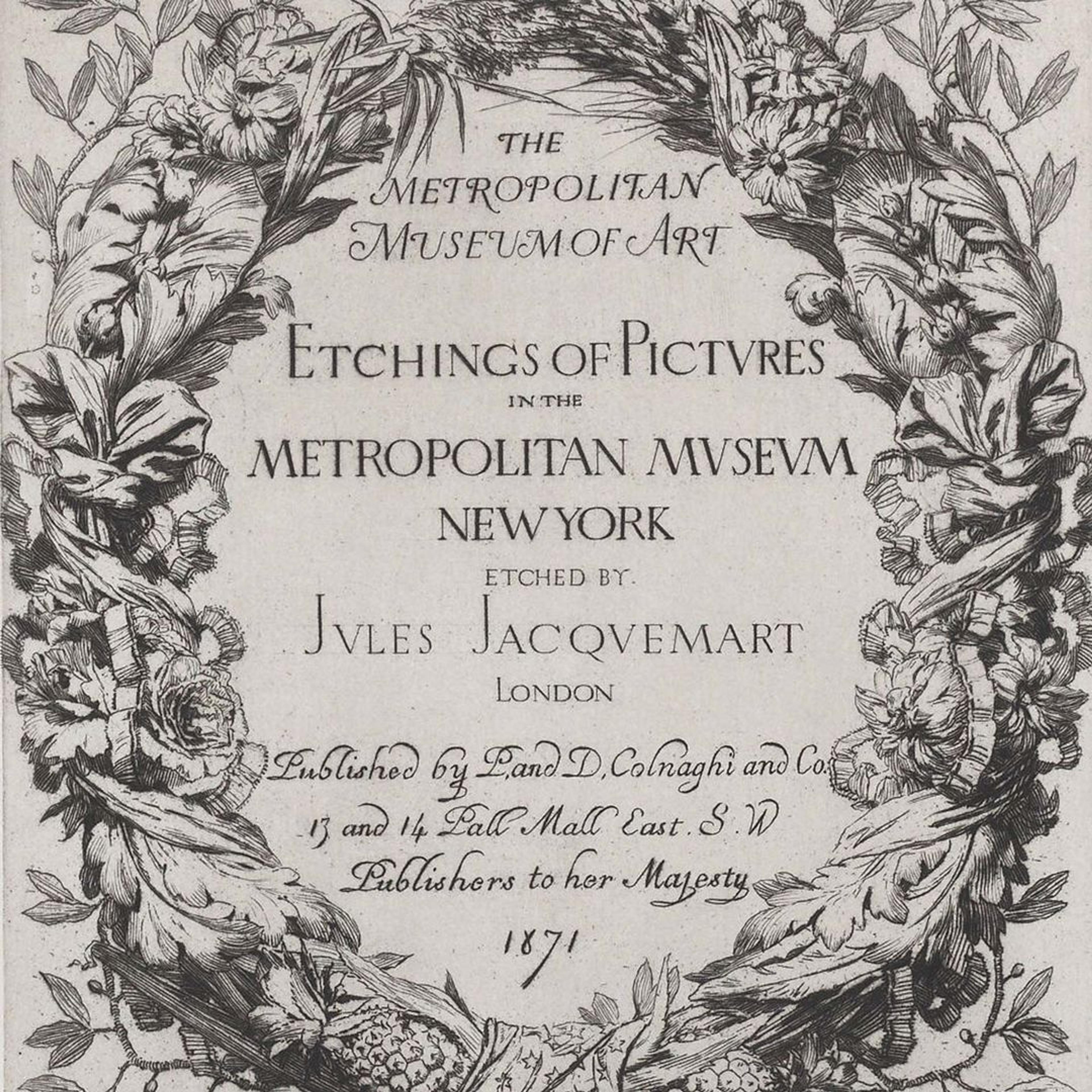

As part of its 150th-anniversary celebration, The Met invited a group of artists with strong ties to the Museum to contribute original prints to The Met 150 portfolio. While COVID-19 inevitably delayed production, its publication in 2021 marks a different anniversary: 150 years since the Museum first commissioned prints from a living artist. Although The Met 150 portfolio is considerably more global in scope, the 1871 project was also an international affair—initiated in Brussels, printed in Paris, published in London, and sold in New York. Executed during a period of political and social turbulence, the Jacquemart portfolio stands as an important precedent that demonstrates the Museum's longstanding engagement with contemporary practitioners and the print medium even prior to the formation of the Department of Prints in 1916.

In 1871, the newly established Metropolitan Museum of Art engaged preeminent French etcher Jules Jacquemart to create a series of prints reproducing paintings from the founding collection. Jacquemart made his name producing still-life etchings and illustrations of objects. [1] He received great acclaim for the sixty plates he contributed to Henry Barbet de Jouy’s Les gemmes et joyaux de la couronne (The Crown Jewels, 1865), a catalogue of the most important Medieval and Renaissance decorative objects in the French royal collection.

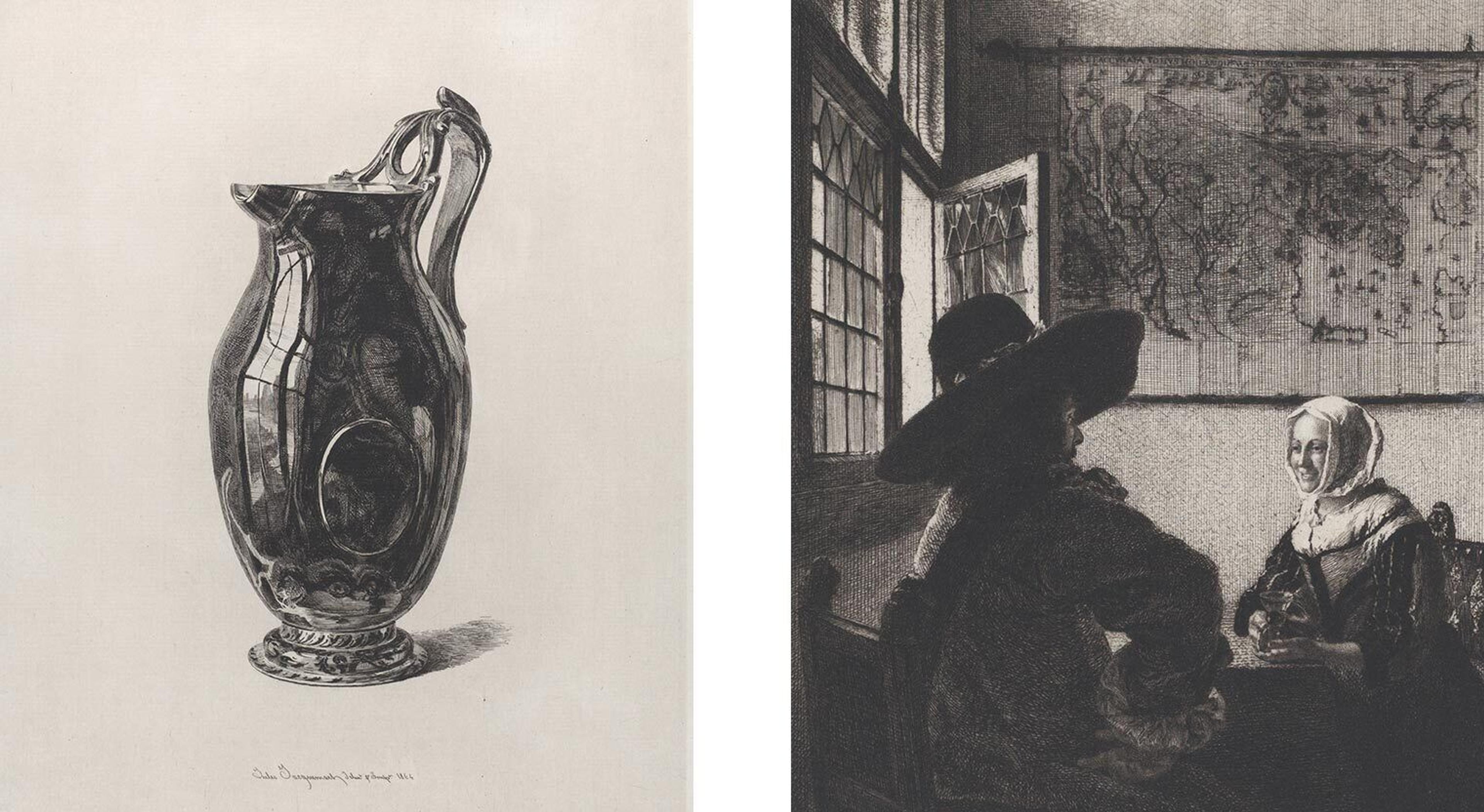

Each plate in The Crown Jewels displays Jacquemart’s virtuosic ability to describe the variety of precious materials, their textures, as well as the play of light on their surfaces. For example, the polished surface of an antique carnelian vase reveals a reflected view of the Louvre through the window of the palace’s studio where the artist worked directly from the objects. He earned two medals for the prints when he exhibited them at the Salons of 1865 and 1866.

Left: Jules-Ferdinand Jacquemart (French, 1837–1880). Antique Carnelian Vase, 1864. Etching, sheet: 19 5/16 × 14 9/16 in. (49 × 37 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Howard Mansfield, 1917 (17.6.2) Right: Jules-Ferdinand Jacquemart (French, 1837–1880). Officer and Laughing Girl, after Vermeer, ca. 1866. Etching, sheet: 19 1/8 × 13 7/8 in. (48.5 × 35.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Theodore De Witt, 1923 (23.65.1)

From three-dimensional objects, Jacquemart turned to paintings as a challenge to his skill with the etching needle. His first successful etching after a painting, Vermeer’s Soldier and the Laughing Girl, appeared in 1866 in the Gazette des Beaux-Arts, an art journal that played a significant role in promoting etching.

The Met’s first print commission was integrally tied to the purchase that year of 174 paintings for the fledgling institution. Against the backdrop of the 1870 Franco-Prussian War and due, at least in part, to the destabilizing impact of that conflict, William Tilden Blodgett, the first Vice President of the Board and Chairman of the Executive Committee, acquired three groups of old master paintings while visiting Europe in the late summer and early fall. He bought two of these collections in Paris from Belgian dealer Léon Gauchez, who likely conceived of the print project for the Museum and suggested Jacquemart as the artist. [2]

With the onset of the Siege of Paris in September, Blodgett and Gauchez fled to Brussels. Jacquemart, meanwhile, enlisted in the National Guard to defend the French capital as one of the tirailleurs de la Seine, a brigade of sharpshooters that included a number of artists, among them fellow etcher James Tissot. Jacquemart remained in the city through much of the Commune—the popular uprising against the royalist-leaning government—but left with his family for Brussels during the Bloody Week that marked its brutal suppression.

According to a receipt in The Met’s archives, Gauchez made his first recorded payment to the etcher on May 23, 1871, presumably while they were both in Belgium. Back in Paris by autumn, the etcher gave his plates to François Liénard to print an initial one hundred sets in mid-November. They were officially published by print sellers P. & D. Colnaghi & Co. in London that December. Although the publisher’s circular announced the project as an ongoing series, it never advanced beyond the first group of ten prints.

By commissioning and circulating the prints, the Museum’s founders promoted their enterprise at home and abroad. This venture was, however, more than just an effective means of publicity. When The Met selected etching as the series’ medium, it entered a lively and ongoing debate around the graphic arts of the time.

In the decade leading up to the Museum’s founding, etching was increasingly in vogue. The Société des Aquafortistes (Society of Etchers), formed in 1862 by the publisher-dealer Alfred Cadart and a group of Paris-based artists, including Jacquemart, was instrumental in advancing the medium. Its popularity spread quickly to Britain and the United States. The Society and its proponents explicitly positioned etching in opposition to photography—increasingly used to reproduce artworks by the end of the 1860s—and equally against engraving, the intaglio technique traditionally associated with high-quality reproductive prints in the nineteenth century. The Museum’s first annual report in 1872 acknowledged these competing media when describing the endeavor:

For publishing representations of paintings, photography is available, and will become more and more so, as American photographers gain skill and acquire the ambition to do such work; and engraving on copper will always be more or less available. … But to the Museum was offered … the services of a most admirable etcher, Mr. Jules Jacquemart of Paris, and most fortunately it has been able to take advantage of the opportunity.

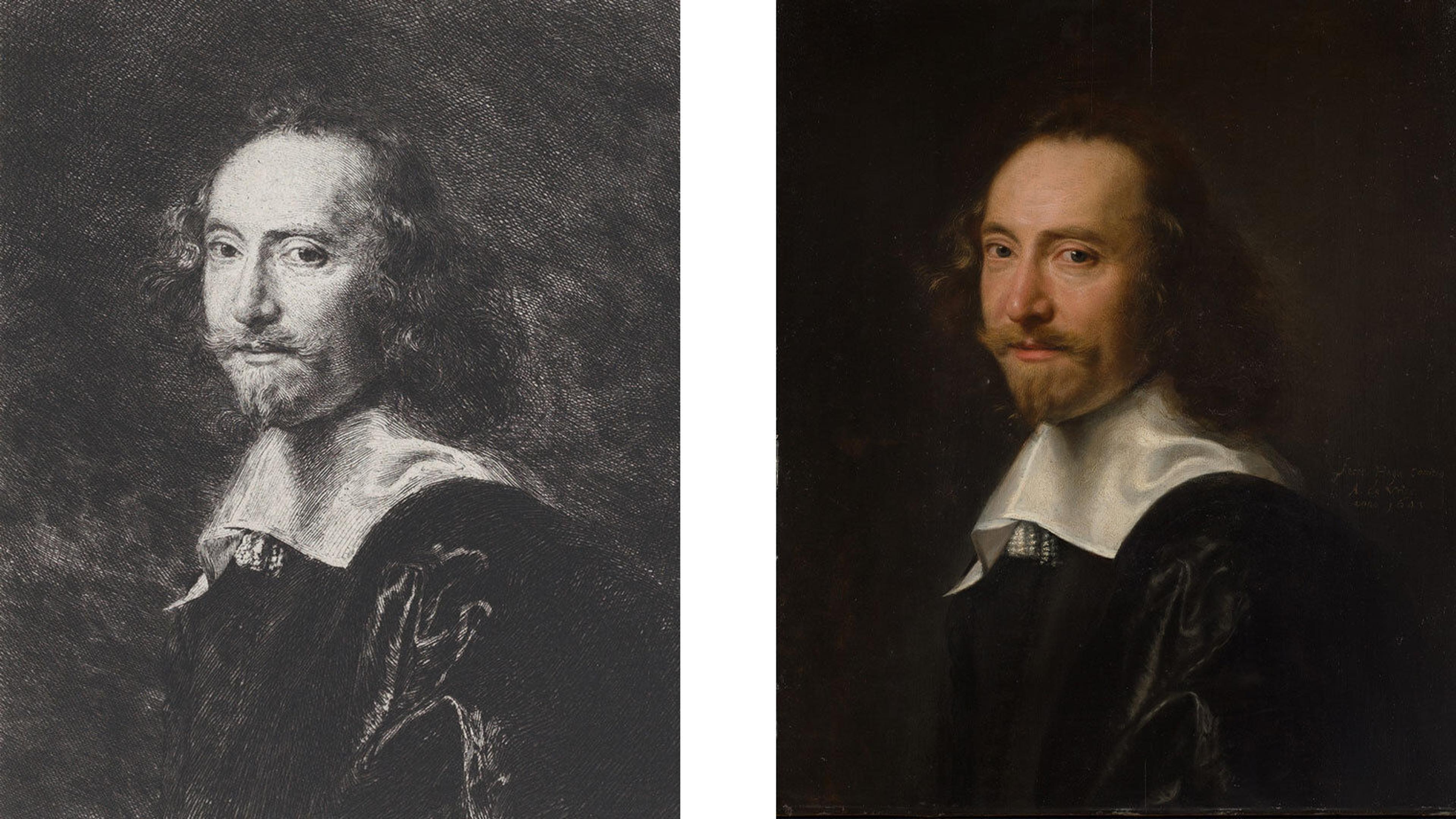

In his review of the Jacquemart portfolio, Philip Gilbert Hamerton, a major promoter of etching in England, was also explicit about the contest at stake between graphic techniques. He cites the “soft and rich” workmanship of the print after Adrien de Vries as a “good instances of the intensity of blacks that can be obtained in etching, and which constitute one of its superiorities over woodcuts and photographic reproductions.” Advocates touted etching as a medium suited to painterly effects and sensitive to the practitioner’s subjectivity. Hamerton underlined this point in his article, claiming “no art is so suitable as etching to the dissemination of the conceptions of painters.” [3]

Left: Jules-Ferdinand Jacquemart (French, 1837–1880). A Dutch Gentleman, after Adriaen de Vries, 1871. Etching, sheet: 18 1/2 × 13 3/8 in. (47 × 34 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, 1871 (19.59.9) Right: Abraham de Vries (Dutch, ca. 1590–1649/50). Portrait of a Man, 1643. Oil on wood, 25 1/4 x 21 in. (64.1 x 53.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, 1871 (71.63)

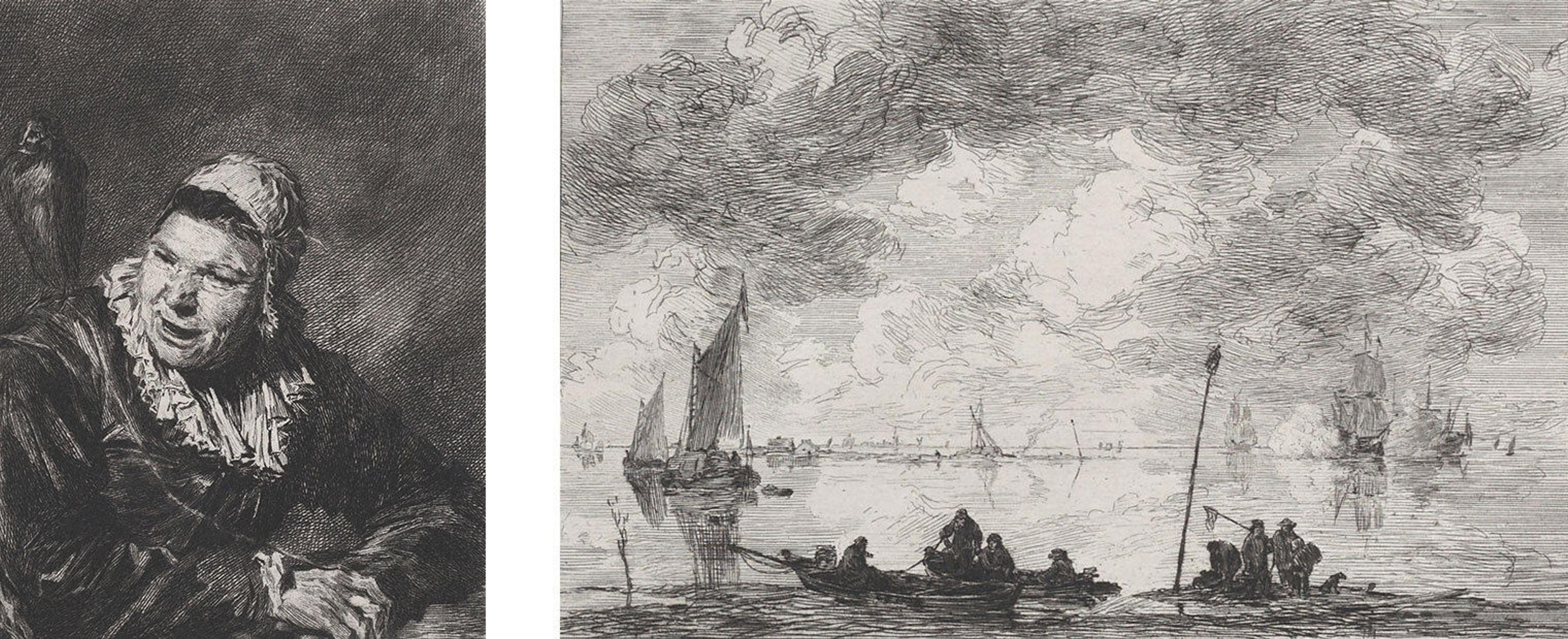

It is a testament to the quality of the objects selected that nine of the paintings included remain in The Met collection today and, among those, only two have changed attribution. [4] Of the ten works represented, one is French and the rest are from Northern schools; nevertheless, there is considerable stylistic variation among the group. Critics lauded Jacquemart’s ability to convey the array of artistic styles. An article published first in the Revue des deux mondes (and reprinted in translation in the New York Herald) called the artist “unrivaled in his power of seizing the expression and character of the work of art he copies.” [5] Pointing to specific examples, another critic wrote, “his needle, which knows no obstacles, translates in turns the frank and choppy touch of Hals and … the puffy clouds of Van Goyen’s marines.” [6]

Left: Jules-Ferdinand Jacquemart (French, 1837–1880). Malle Babbe, after Frans Hals,1871. Etching on chine collé, sheet: 18 7/8 × 13 3/4 in. (48 × 35 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1912 (12.191.26) Right: Jules-Ferdinand Jacquemart (French, 1837–1880). The Moerdyck, after Jan van Goyen, 1871. Etchings, sheet: 13 in. × 18 7/8 in. (33 × 48 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, 1871 (19.59.6)

The reproductive aim of Jacquemart’s prints mark a key distinction from The Met 150 portfolio, which features original artworks by diverse artists. (Although it resonates intriguingly with Robert Rauschenberg’s Centennial Certificate MMA, produced for the Museum’s 100th anniversary, which incorporates reproductions of works from the collection.) Importantly, reproductive prints held a markedly different status in 1871 than they do today. Jacquemart’s etchings were not perceived as facile copies, but rather as interpretive reproductions. Hamerton credits them with providing “the double pleasure of well-selected originals and the most sympathetic interpretation.” He goes so far as to credit Jacquemart’s descriptive power as exceeding that of an art critic: “It is all very well to write criticisms on works of art, and say that we appreciate them for this or that quality … but what commentary ever went into the matter so incisively as Jacquemart’s etching needle?” [7] This assessment emphasizes both Jacquemart’s critical subjectivity and manual skill in creating the prints.

As a promotional venture, the portfolio was particularly successful at earning attention abroad. It garnered additional reviews in The Art Journal and The Graphic in Britain and the Gazette des Beaux-Arts and La Republique française in France, among others. Louis Decamps noted in the Gazette that The Met “shows itself at the outset to possess a great number of the works of masters whose importance is attested by the [etching needle] of a French artist of splendid talent.” [8] Jacquemart’s reputation and work shone favorably on the new museum. In addition to the critical success of the etchings, the artist was evidently pleased with his work, as he elected to exhibit them at the Salon of 1872.

From a commercial perspective, however, the portfolio was a flop. In 1876, Colnaghi, the publisher, wrote that the prints were not selling well and by 1879, the print-seller Goupil said they “do not expect any success with them.” [9] The failure to attract many buyers beyond Museum trustees may reflect the changing attitudes about originality in printmaking that occurred in the last quarter of the nineteenth century—especially in the luxury market at which the portfolio was aimed. The discourse of the etching revival, which emphasized originality over reproduction, won out. For twenty-five dollars a set, the serious print collector of the period likely expected to purchase an originally conceived work of art. Nevertheless, today the Jacquemart portfolio speaks volumes for the The Met’s early ambitions, its engagement with the finest artists of the day, and its investment in the print medium for circulating works of art beyond the Museum’s walls.

Many thanks to Jacqueline Banigan, MUSE Intern, for cataloguing these works in 2019 and to Donato Esposito, who initially called my attention to them.

[1] For more on Jacquemart, see: James A. Ganz, “Jules Jacquemart: Forgotten Printmaker of the Nineteenth Century,” Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin 87, no. 370 (1991): 1-24. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3795452. Return

[2] Katharine Baetjer, “Buying Pictures for New York: The Founding Purchase of 1871,” Metropolitan Museum Journal, Vol. 39 (2004): 161-245. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40034606. Return

[3] Philip Gilbert Hamerton, “Jacquemart’s Etchings from Pictures,” The Portfolio vol. 4 (1873): 16. Return

[4] For reasons of condition, The Moerdyck was sold as attributed to Jan van Goyen at Sotheby's, January 12, 1989, no. 50. See Baetjer, Appendix 1: Part B, no. 128. Portrait of a Woman, formerly given to Lucas Cranach the Younger, was reattributed to Bernhard Strigel and Malle Babbe, which entered the collection as Frans Hals, is now considered “School of.” Return

[5] “The Metropolitan Museum of Art. A Complimentary Notice by the Secretary of the Late Emperor Napoleon’s Minister of Fine Arts—The Splendid Collections Made in Europe” New York Herald, Nov 22, 1871, 4. Return

[6] René Menard, La Gravure au Salon, Gazette des Beaux-Arts 6:182 (August 1, 1872): 123. Return

[7] Hamerton, “Jacquemart’s Etchings from Pictures,” 14. Return

[8] Louis Decamps, “Un Musée transatlantique,” Gazette des beaux-arts vol. 5 (January 1872): 33. Return

[9] Letter from P. & D. Colnaghi, March 24, 1876 and Letter from F. H. Tripp of Goupil & Cie. to Samuel P. Avery, August 9, 1879, Museum Archives. Return