John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925). Gassed, 1919. Oil on canvas, 23.1 x 61.1 cm. Imperial War Museum, London (Art.IWM ART 1460). Image © IWM

«Best known for his bravura society portraits and dazzling, sun-filled watercolors, the cosmopolitan American painter John Singer Sargent (1856–1925) might seem an unlikely candidate to document the Great War. Yet, in summer 1918, the 62-year-old painter traveled to France and Belgium as an official war artist for Britain. At the time, he was one of the most esteemed painters of his day, widely recognized in the United States and Europe for his portraits and for his mural work at the Boston Public Library and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Having accepted a commission to commemorate the joint efforts of American and British troops for a proposed Hall of Remembrance, Sargent spent four months at the front, sketching and painting in watercolor as he grappled with how to convey the magnitude and loss of the devastating war in a monumental composition.»

He ultimately abandoned his assigned theme, choosing instead to depict the impact of modern chemical warfare. Gassed (above)—an epic, frieze-like composition depicting soldiers blinded by mustard gas being led to treatment—was based on a scene that he had witnessed at Le-Bac-du Sud on the Arras-Doullens Road in August 1918. Along the side of the road, hundreds of injured soldiers convey the devastating human toll and horrific scale of the war.

Sargent's very public response to the war incorporated associations of his personal grief and loss. Months earlier, his beloved niece (and frequent model) Rose-Marie Ormond had been killed in the bombing of the church of Saint-Gervais in Paris on Good Friday. Only 24 years old at the time of her death, Rose-Marie had worked as a nurse treating blinded soldiers after her husband, Robert, died fighting for France in October 1914. Sargent likely associated the wounded soldiers in Gassed with her role in the war effort.

Four years earlier, when England and France declared war on Austria on August 4, 1914, Sargent was on one of his customary summer painting holidays in the Austrian Tyrol. Without a passport, he was forced to remain there until November, when he obtained the necessary documents. His letters to Rose-Marie and other family members reveal his concern and anxiety, especially for Rose-Marie's husband. Sargent was in Pustertal, near the Italian border, in late October when he received news of Robert's death.

Left: John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925). Tyrolese Interior, 1915. Oil on canvas, 28 1/8 x 22 1/16 in. (71.4 x 56 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, George A. Hearn Fund, 1915 (15.142.1). Right: John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925). Tyrolese Crucifix, 1914. Watercolor and graphite on white wove paper, 21 x 15 3/4 in. (53.3 x 40 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1915 (15.142.7)

Sargent was characteristically quite reticent; because of this, some of his friends suggested that he was unperturbed by the war. However, paintings from this period in Austria suggest otherwise: they are unusually meditative and somber in mood. Though he was not traditionally religious, Sargent incorporated religious imagery into several compositions, infusing them with intimations of spirituality and mortality. Tyrolese Interior depicts a group of local farmers sharing their midday meal in a converted castle. On the shelf and wall above, they are surrounded by statues of religious figures and a crucifixion, and dramatic light from the window at right casts an ethereal glow.

In Tyrolese Crucifix, Sargent depicted a roadside shrine against a gnarled tree. Such shrines across this region in Austria were common sites—often commemorative in function—serving as a place for travelers to stop and pray on their route. Sargent positioned himself below the shrine to concentrate on the bark of the tree and the lifeless figure of Christ as if he were praying. The image of Sargent poised beneath the shrine painting calls to mind the Latin motto that would later be inscribed on his tombstone in 1925: Laborare est Orare or "To work is to pray."

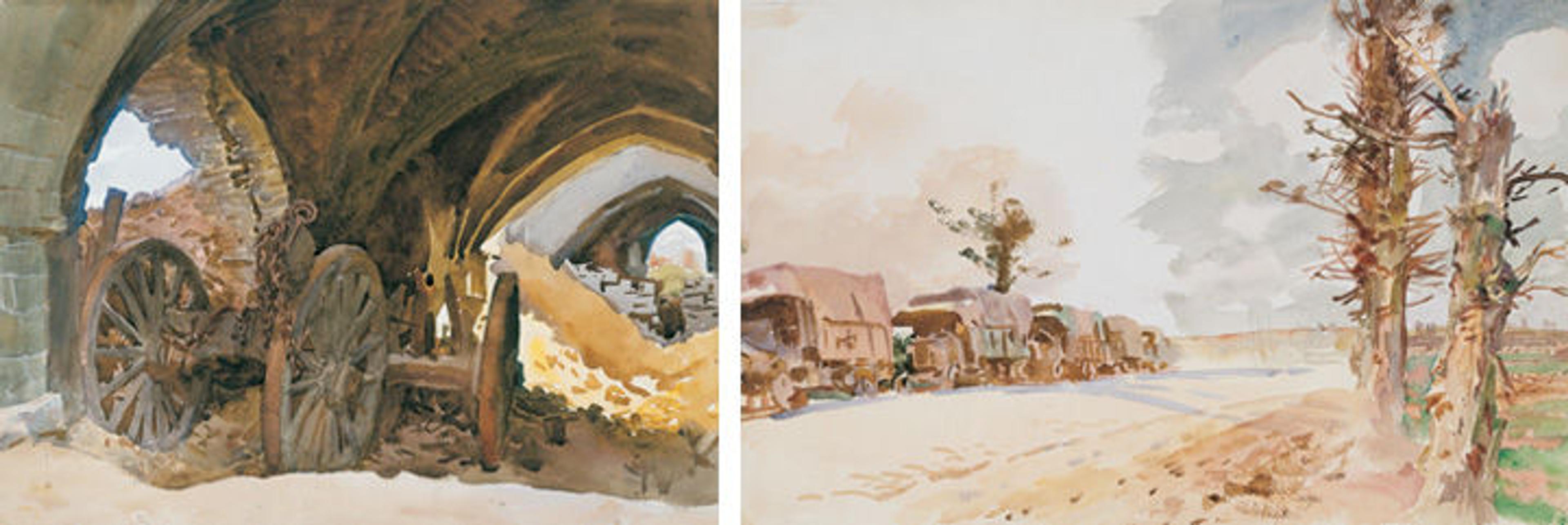

Left: John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925). Wheels in Vault, 1918. Watercolor, graphite, and wax on white wove paper, 15 3/8 x 20 13/16 in. (39.1 x 52.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Francis Ormond, 1950 (50.130.56). Right: John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925). Truck Convoy, 1918. Watercolor and graphite on white wove paper, 13 3/8 x 21 1/16 in. (34 x 53.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Gift of Mrs. Francis Ormond, 1950 (50.130.54)

In 1950, The Met's Sargent holdings were amplified by a major gift from the artist's sister Violet Ormond. Among the collection of more than 300 works—mostly drawings and watercolors—were 17 sheets made during Sargent's time at the front. Many of these works, such as the evocative Wheels in Vault or the more documentary Truck Convoy, were unfinished and not exhibited in the artist's lifetime. These sheets reflect Sargent's search for a subject for his commission and often relate to more formal war compositions, many of which are in the collection of the Imperial War Museum in London.

John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925). Two Soldiers at Arras, 1918. Watercolor and graphite on paper, 6 7/8 x 9 1/2 in. (17.5 x 24.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Promised Gift of Jacqueline Loewe Fowler (L.2017.25.21)

Two Soldiers at Arras, a recent generous promised gift to The Met from Jacqueline Loewe Fowler, presents the danger of chemical warfare on a small and intimate scale. Sargent depicted the two debilitated soldiers against a plain grassy backdrop—the composition tightly cropped and lacking a horizon. The figure at right still wears his gas mask while the figure at left clutches his eyes, underscoring a grave effect of exposure to mustard gas. Two Soldiers at Arras seems to relate to Gassed; its creation may have been part of his artistic process for the monumental composition even though it also served as an independent work of art.

John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925). Tommies Bathing, 1918. Watercolor, gouache, and graphite on white wove paper, 13 5/8 x 20 15/16 in. (34.6 x 53.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Francis Ormond, 1950 (50.138.58)

The physical closeness of the figures as they lie in the grass invites associations with a pair of candid watercolors in The Met collection depicting of the daily lives of the soldiers, which are both entitled Tommies Bathing. In one (above), Sargent renders a peaceful, off-duty moment for a group of British soldiers known as "Tommies": two of them lounge in the long grass while a third bathes nearby.[1] In a second iteration (below), two naked soldiers seem relaxed and vulnerable as they sleep on a tuft of grass alongside the water. Sargent never exhibited these candid watercolors, the intimacy of which has, in more recent years, provoked curiosity about his sexuality.[2]

John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925). Tommies Bathing, 1918. Watercolor and graphite on white wove paper, 15 5/16 x 20 3/4 in. (38.9 x 52.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Francis Ormond, 1950 (50.138.48)

Currently at The Met Fifth Avenue, you can consider some of Sargent's public and private responses to the war in two different locations and contexts: Wheels in Vault—as well as a selection of drawings and a study for The Coming of the Americans—is on view in the exhibition World War I and the Visual Arts in galleries 691–93 through January 7, 2018; and Tyrolese Interior and a small selection of World War I watercolors by Sargent are on view in gallery 770 of The American Wing.

Notes

[1] The nickname "Tommies" for British soldiers came from the name Thomas Atkins, which was the generic name used on government documents (similar to the American John Doe).

[2] Sargent was intensely private. Although it seems likely that Sargent was gay, he left no evidence of relationships with men or women. He lived most of his adult life in England where sodomy was illegal.

Related Links

World War I and the Visual Arts, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through January 7, 2018

Read more blog posts in this exhibition's Now at The Met series.