Cover of The Butcher, the Baker, the Candle Stick Maker: Images of Labor: An Exhibition. New York: Pratt Graphics Center Gallery, 1977

«Most of the world celebrates International Workers' Day, or Labor Day, on May 1, which was established by the Second International to commemorate the Haymarket affair (or "massacre" or "riot," depending on who's telling the story) that saw violence and persecution descend on Chicago as workers demonstrated for an eight-hour workday. To this day the Haymarket affair is one of the most significant events in United States labor history, and workers the world over continue to honor it with annual May Day celebrations.»

It is ironic, then, that the country whose Haymarket Affair sparked such international solidarity among workers no longer celebrates Labor Day on May 1, but instead is one of only two countries to do so (along with Canada) on the first Monday of September. Although we no longer celebrate Labor Day with the rest of the world, the United States, like so many other countries, has a rich tradition of depicting workers in art. From farmers to factory workers, laborers across the U.S. and the world have inspired artists for centuries, and Watson has dozens of books on the diverse ways workers have been represented in art internationally.

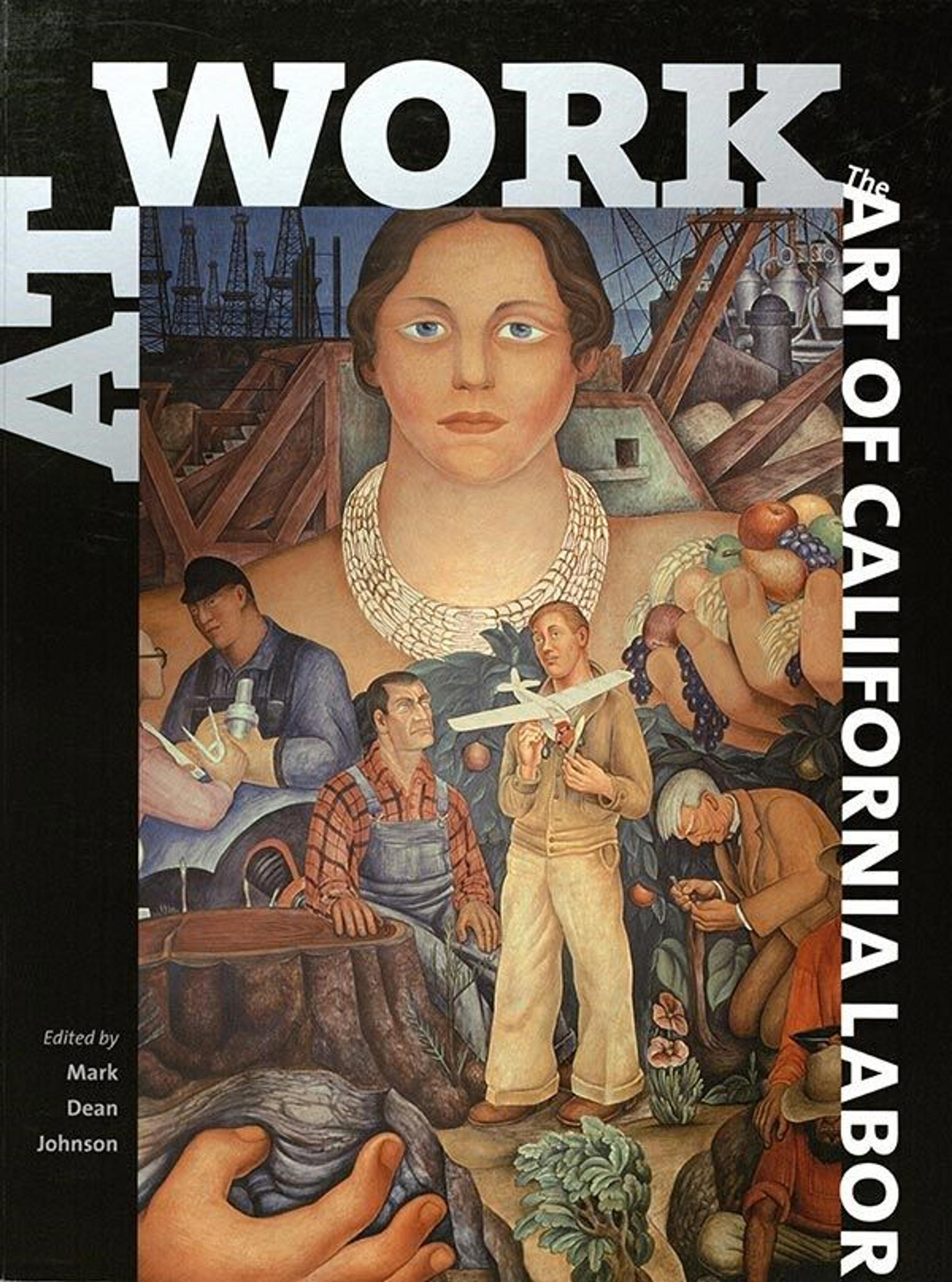

Cover of At Work: The Art of California Labor. San Francisco: California Historical Society Press in conjunction with Heyday Books, San Francisco State University, and the California Labor Federation, AFL-CIO, 2003

The cover of the exhibition catalogue At Work: The Art of California Labor is adorned with a painting, Allegory of California (1931), created not by an American artist but by the great Mexican muralist Diego Rivera. In it, Rivera captures the economic dynamism of a state that would go on to become the largest economy in the U.S.—showcasing everything from its robust agricultural output to its cutting-edge industrial and transportation marvels. This is very much in line with the catalogue as a whole, which gathers together over a century's worth of art depicting the constantly shifting nature of work in a state that has become such a vital part of the world economy. Rivera humanizes this relentless economic growth, and places workers squarely at the center of it.

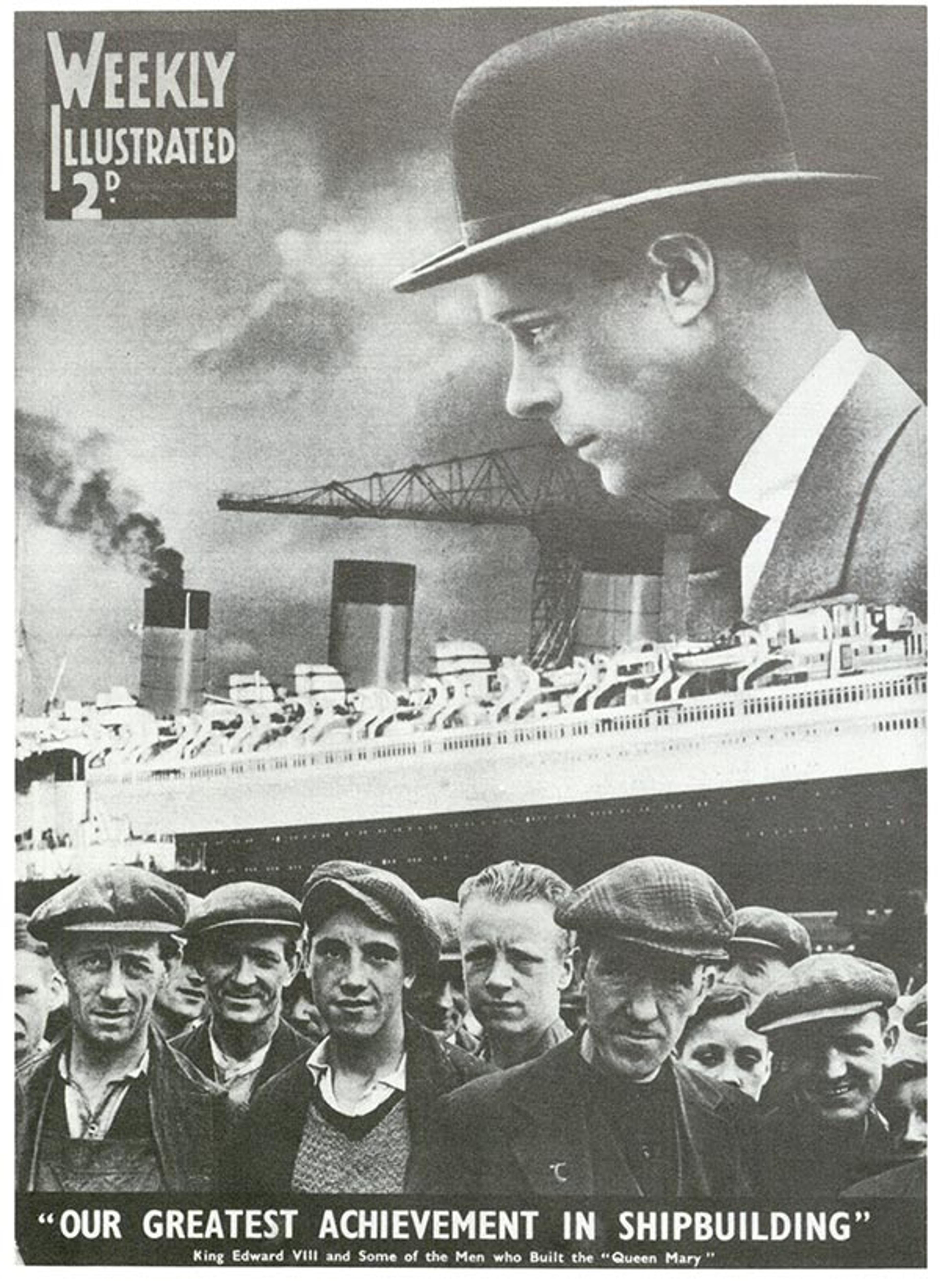

From The British Worker: Photographs of Working Life 1839–1939. London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1981

This photograph by James Jarché comes from an exhibition catalogue that explores a century of photographs of British workers. The image served as the cover of a 1936 Weekly Illustrated and, as the catalogue's caption notes, represented the "plight of Jarrow." In October of that year, some two hundred workers from the northern town of Jarrow marched three hundred miles to London to protest what had become unbearable levels of unemployment (nearly seventy percent of the town was without a job after its main employer, Palmer's shipyard, left Jarrow the year prior). In this montage, Jarché captures both the dignity and indignation of these laid-off shipyard workers, contrasting the grandeur of what these workers once built ("Our greatest achievement in shipbuilding" reads the caption at bottom) with the harrowing conditions they now confront.

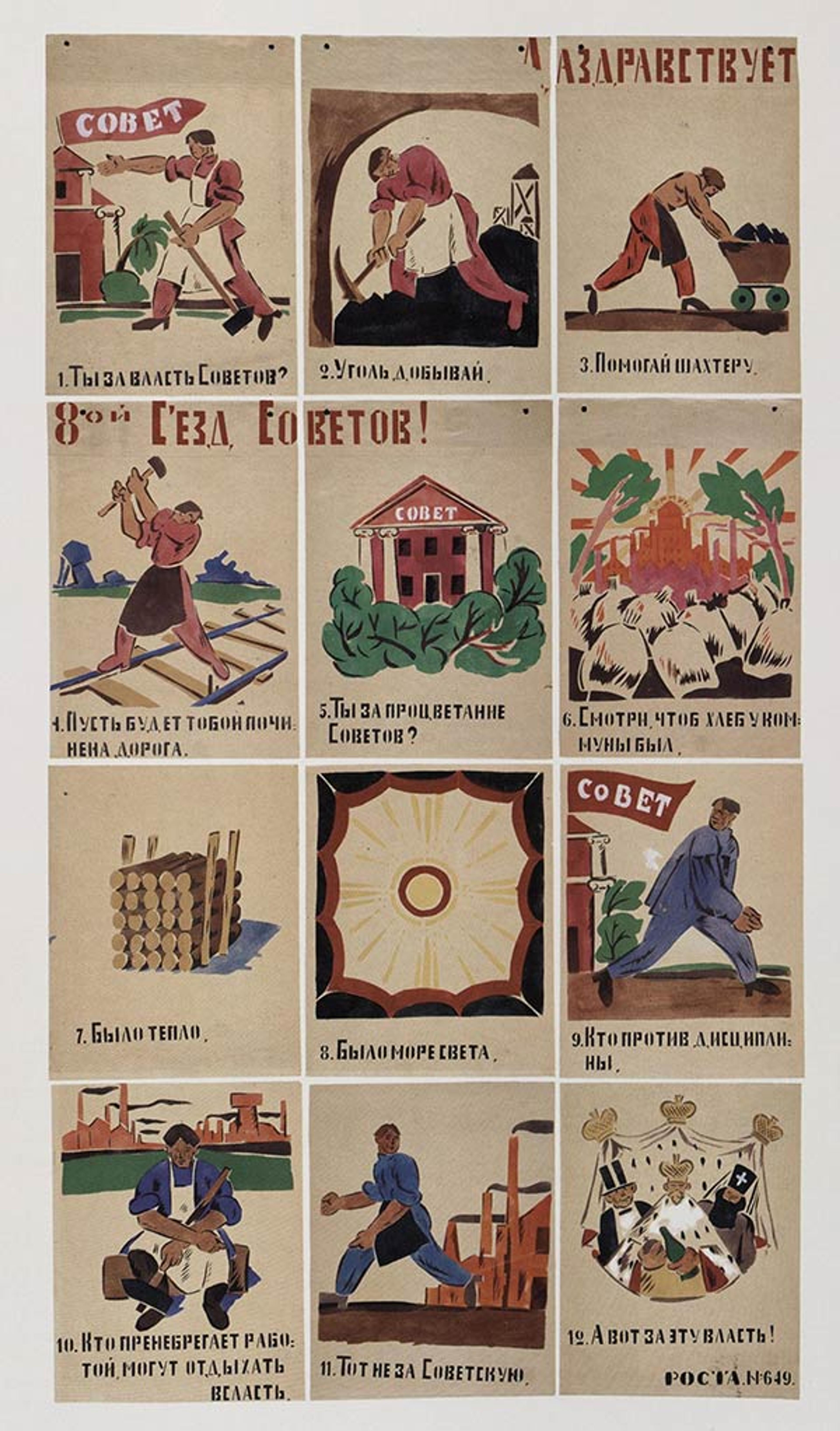

From Power to the People: Early Soviet Propaganda Posters in The Israel Museum, Jerusalem. Jerusalem, Israel: The Israel Museum, 2007

This series of Soviet images, one of many in Power to the People: Early Soviet Propaganda Posters in The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, was produced for the eighth All-Russia Congress of Soviets in Moscow, held in 1920. During this period Russia was still in the midst of a civil war, and food shortages and harsh working conditions were creating a climate of deep discontent. To bolster the spirit of Soviet citizens, art such as this was produced, depicting all sorts of workers—miners, factory workers, railroad laborers—dutifully carrying out their tasks in the face of great obstacles. Their rewards, these images promised, were the electrification of Russia, as captured in panel eight, and radiant communes, as depicted in panel six. Workers, it was understood, were the only hope for elevating Russia out of the morass and depression of civil war.

Related Links

In Circulation: "Oh Say, Can You See . . . Hot Dogs!" (July 1, 2015)

In Circulation: "O Tannenbaum, O Tannenbaum, Your Branches Green Delight Us!" (December 24, 2014)