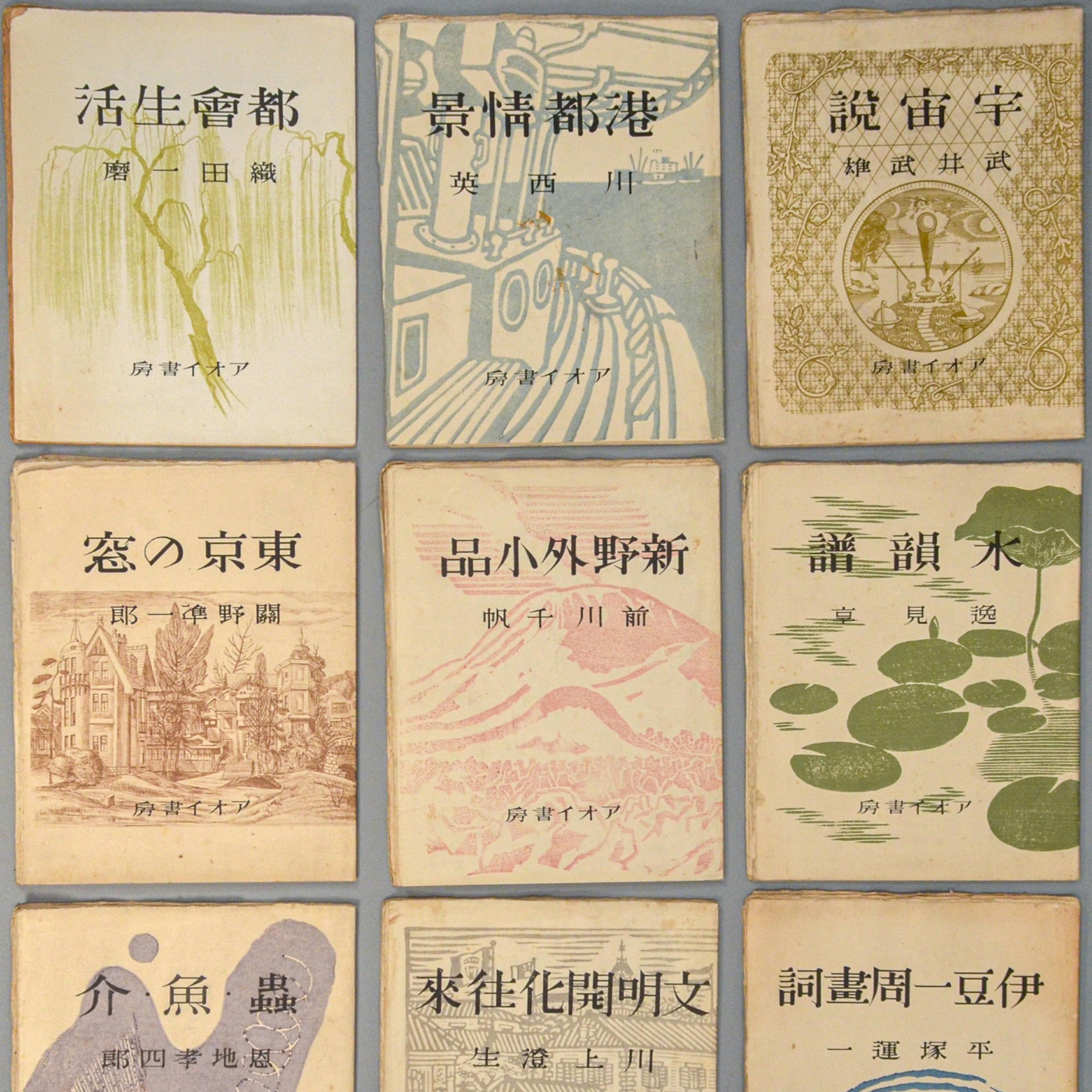

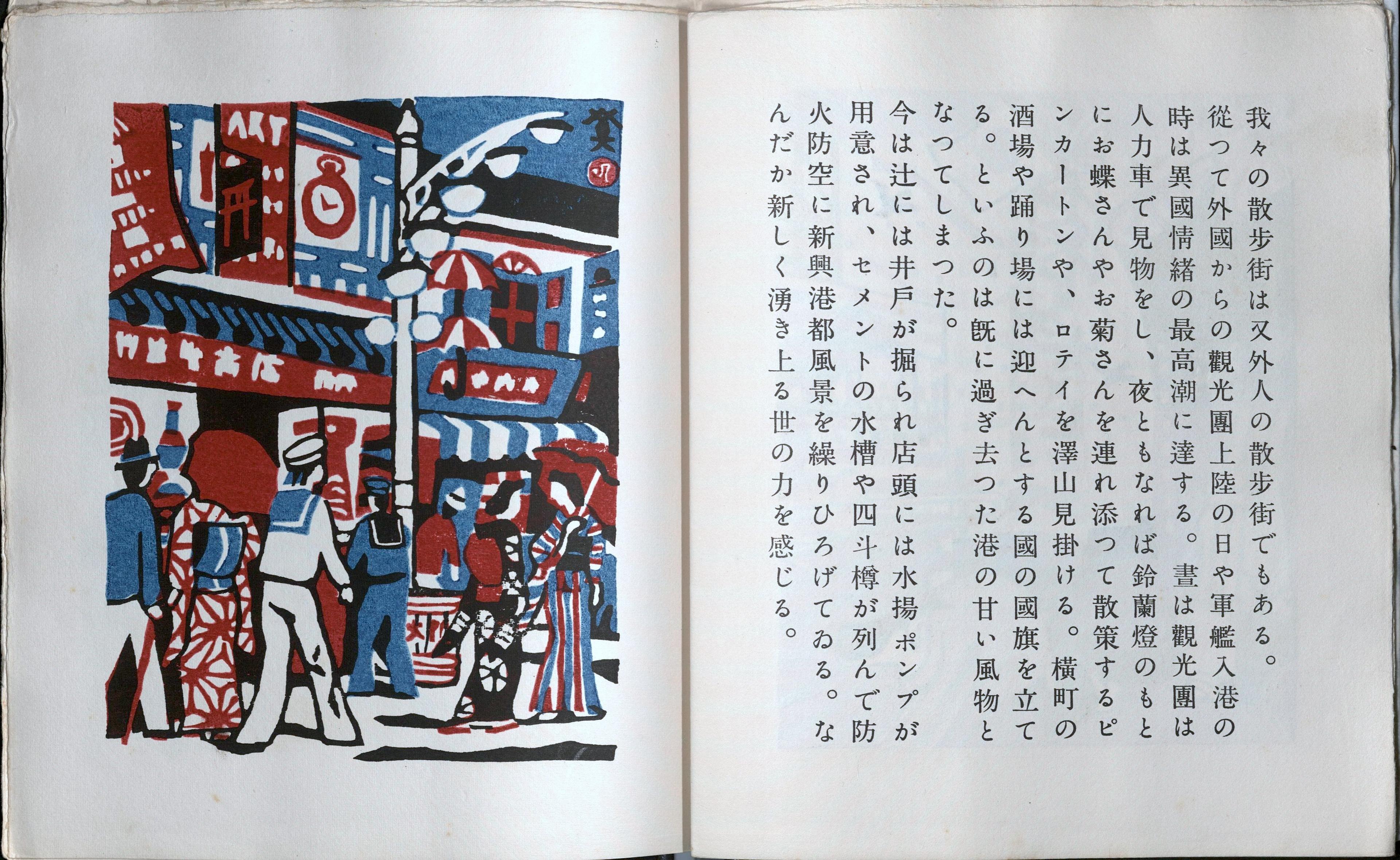

Thomas J. Watson Library recently acquired an important Japanese print portfolio, A Collection of Ten Print Albums Windowing Texts (書窓版画帖十連聚, Shoso hanga-cho ju-renshu). Published by Aoi Shobo and printed in Tokyo between 1941 and 1943, the portfolio contains nine albums, each of which was contributed by a different artist and contains ten prints. The albums were printed on large, heavy sheets of handmade mulberry paper—a rarity during wartime scarcity and rationing. When opened, the left sheet features a woodblock or copper plate print, while the right sheet contains a poetic inscription. The set captures the creative interplay between the literary and the visual arts popular in Japan during the early 1940s.

A Collection of Ten Print Albums Windowing Texts (書窓版画帖十連聚, Shoso hanga-cho ju-renshu). (Tokyo: Aoi Shobo, 1941–1943). Image courtesy of Boston Book Company

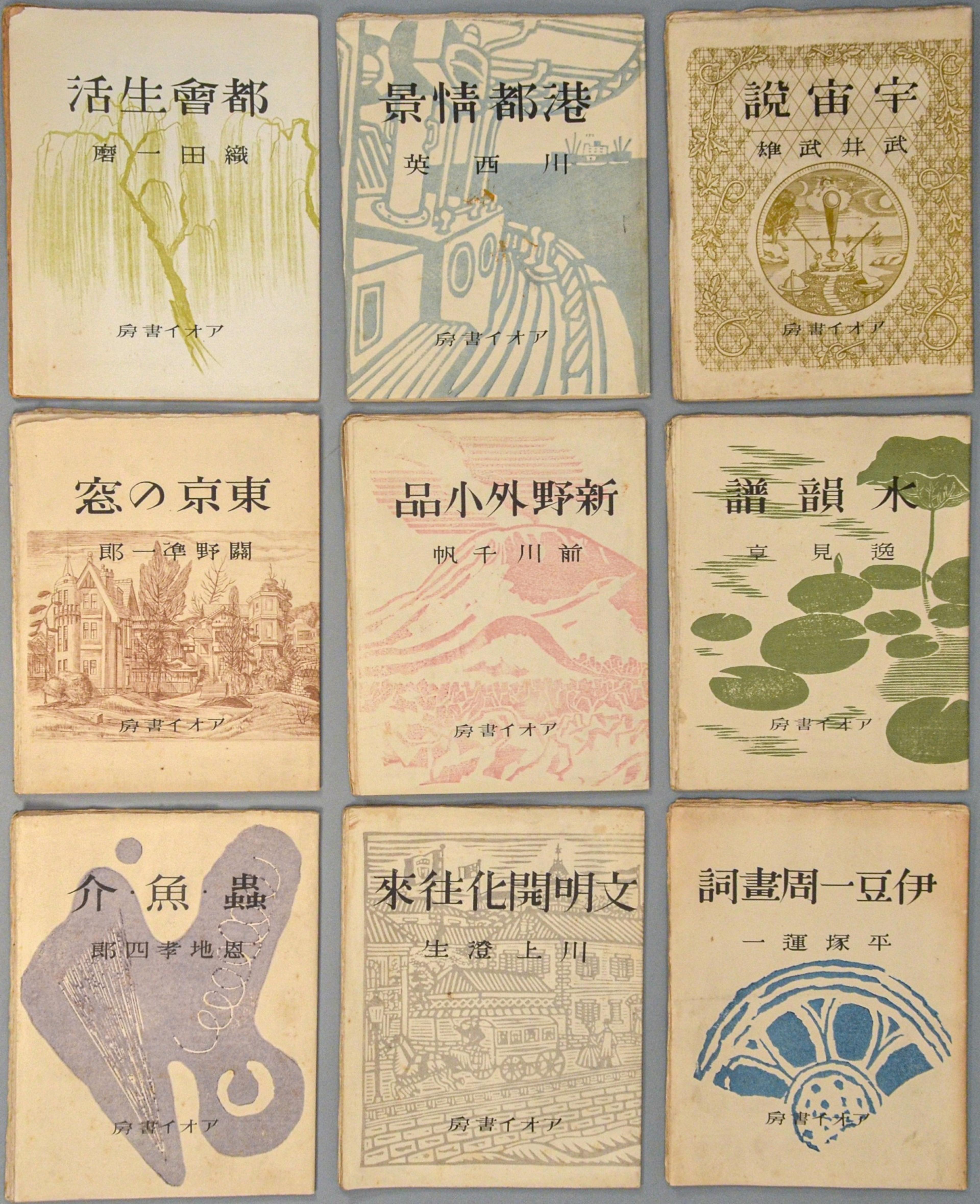

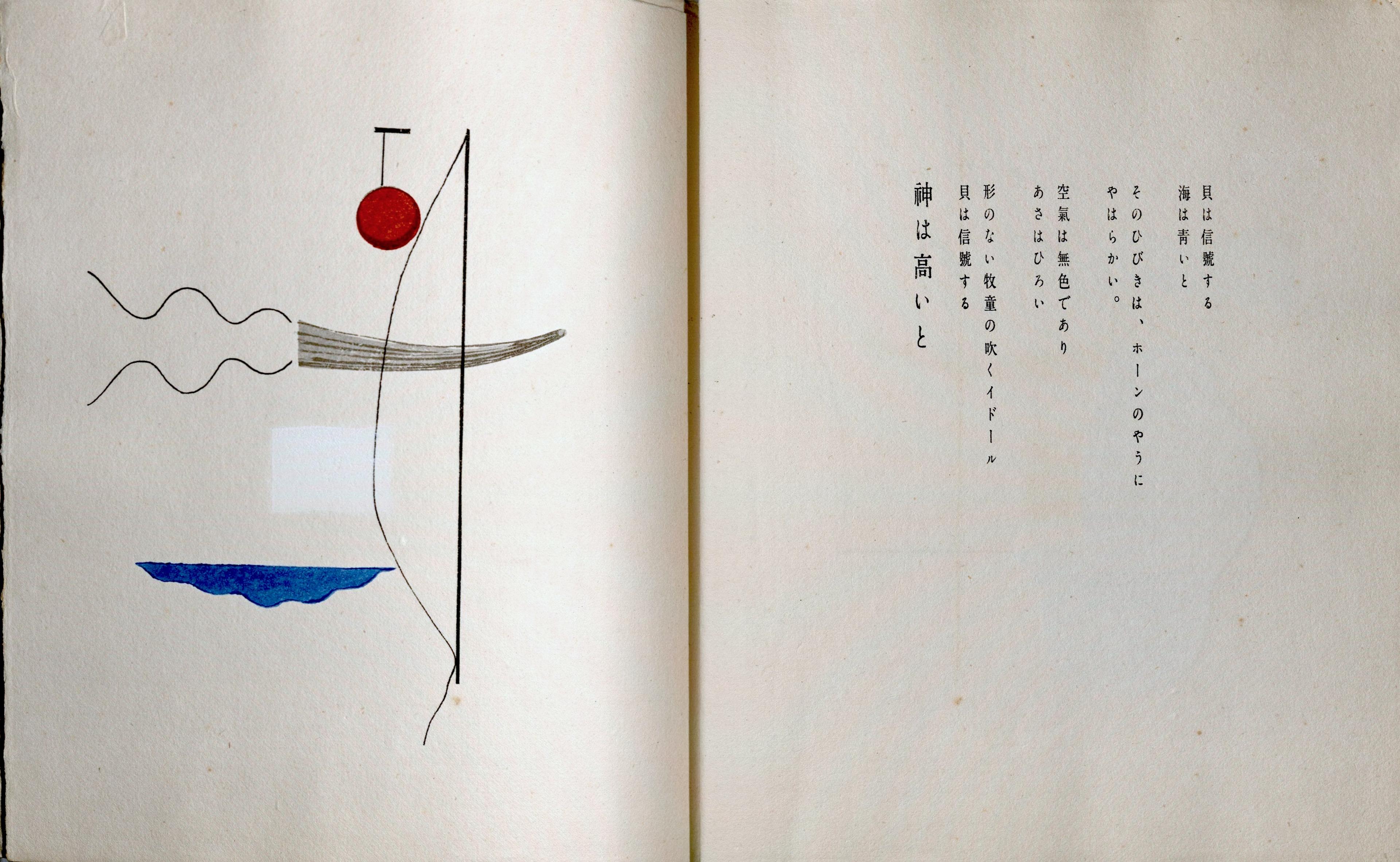

Onchi Kōshirō (恩地 孝四郎, 1891–1955) was the founder and leader of Japan’s Creative Print movement and the Etching Society. This loosely connected group of artists challenged the norms of art created solely for commercial or naturalistic purposes, and produced work on their own terms. Onchi’s contribution in this series, Insects, Fish, and Shellfish (蟲・魚・介, Mushi, uo, kai, 1943), demonstrates his pairing of experimental verses with innovative printing techniques. By merging color woodblocks with mechanically produced half-tone and line block prints, he conveyed subjective emotions through abstract prints. Insects, Fish and Shellfish features ten prints on insects and maritime animals, with poems exploring the dynamic relationships within the natural world.

Insects, Fish, and Shellfish (蟲・魚・介 , Mushi, uo, kai). (Tokyo: Aoi Shobo, 1943)

The companion poem to the spider illustration above was translated by Lawrence Smith in Japanese Prints during the Allied Occupation 1945–1952 (2002):

From where did she come to lay in that stock of mathematics?

On one thread she stares at the heavens

Antennas gleam in the sky

The sticky ball is methodically distributed

TIME TIME TIME

Then it becomes a pendulum

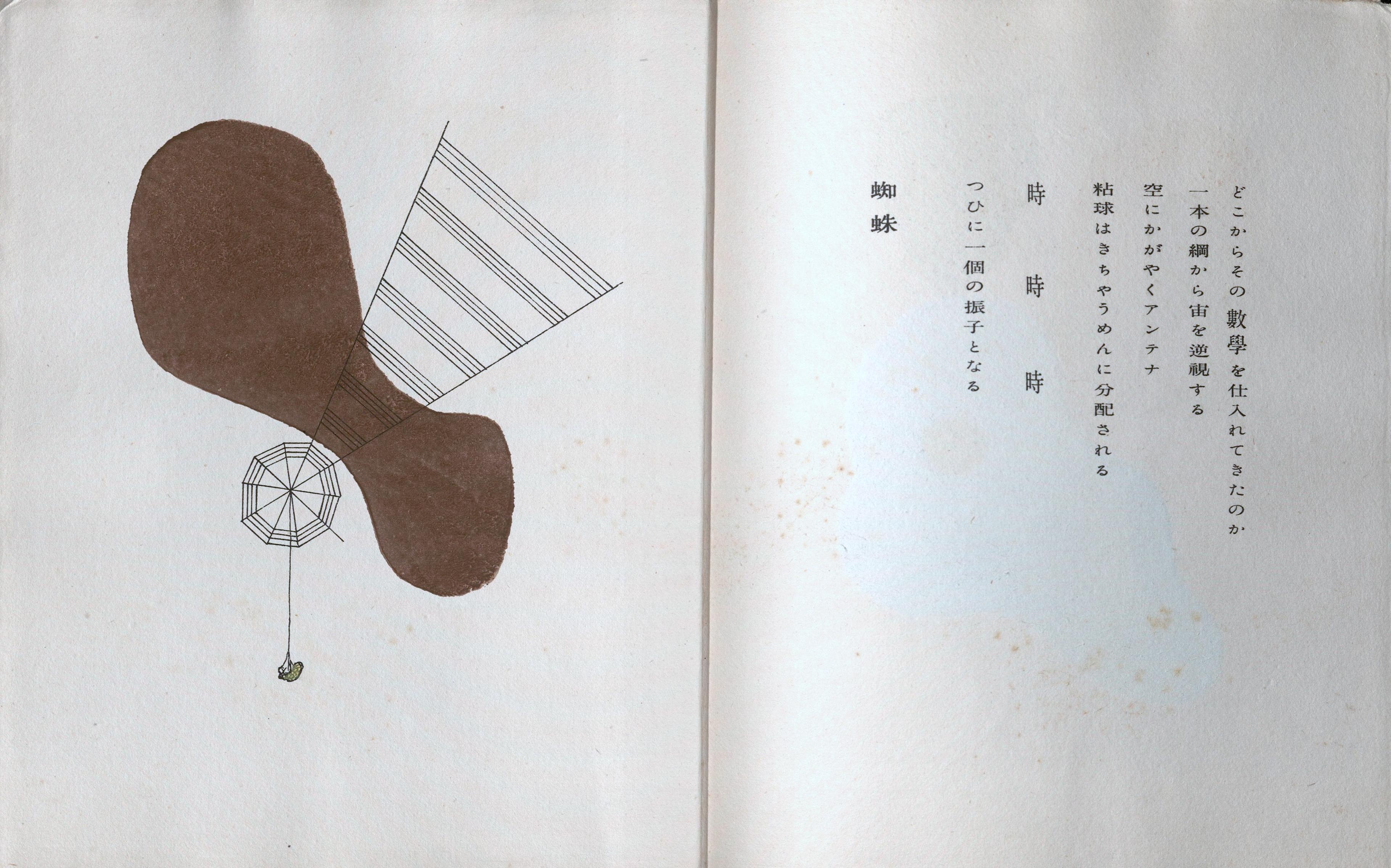

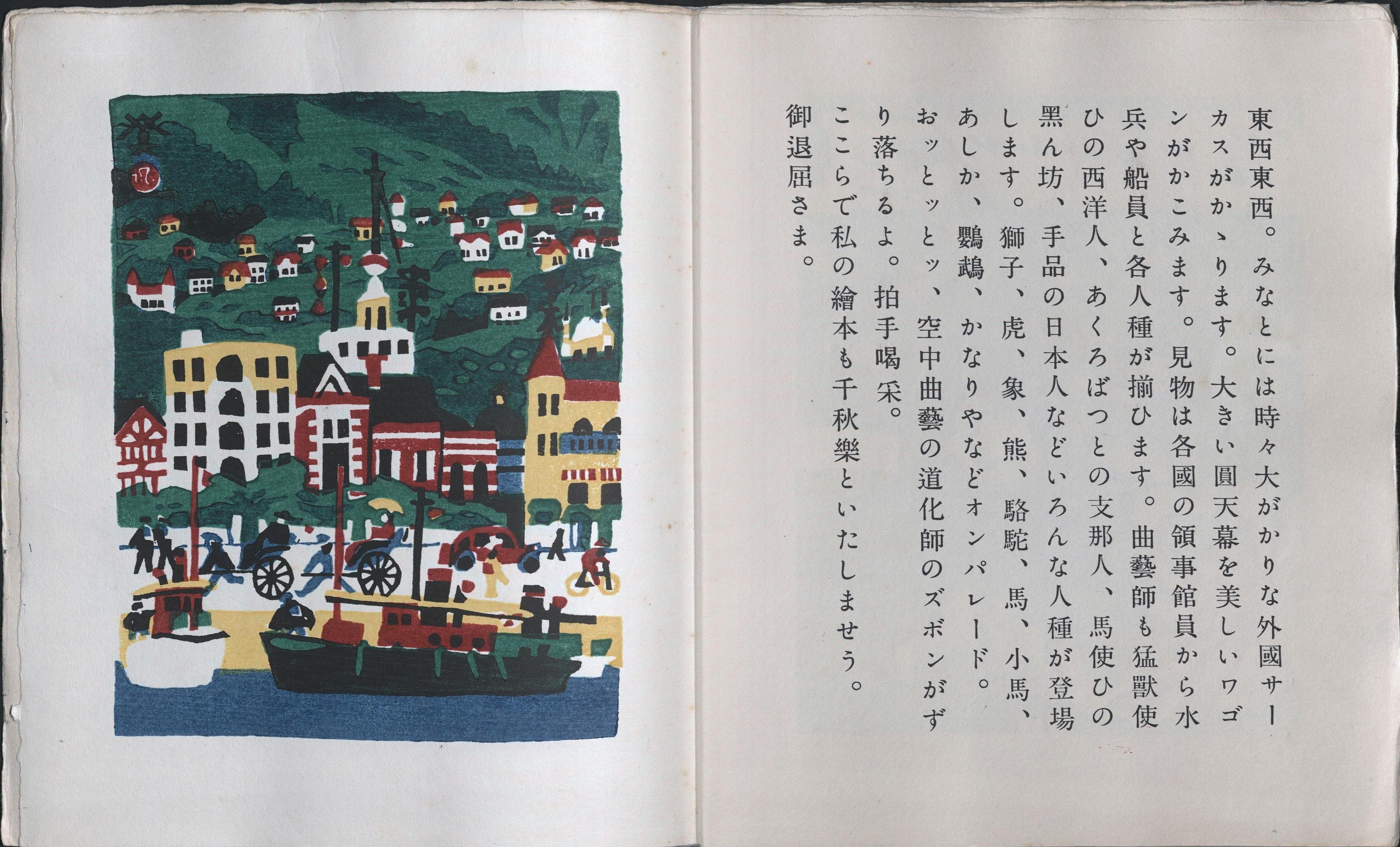

The variety of techniques, media, and topics explored by Japanese printmakers during wartime underscore their diverse interests. The second book in the series, Harbour Scenes (港都情景, Koto Jokei, 1941) by Kawanishi Hide (川西英, 1894–1965), illustrates how a once peaceful trade harbor was transformed for naval use. Amidst escalating global conflict and the height of Japanese expansionism in 1941, as the country extended its influence across East and Southeast Asia, the author invokes a sense of national pride as he observes the harbor filled with ships adorned with symbols of the Japanese military.

Harbour Scenes (港都情景, Koto jokei). (Tokyo: Aoi Shobo, 1941)

Roughly translated, the first paragraph reads:

To indicate our nationality, we painted a large Hinomaru (Japanese flag) on the middle of the steamship, and we were deeply moved to see the ship sailing merrily through turbulent countries and shining its flag with such vigor. When we look at it with those eyes, the Hinomaru shines like a medal on a soldier’s chest. At a time when the international situation is ever-changing, it is only natural that the eyes of Japanese people in a foreign country get excited when they see the Hinomaru on the hull of our ship.

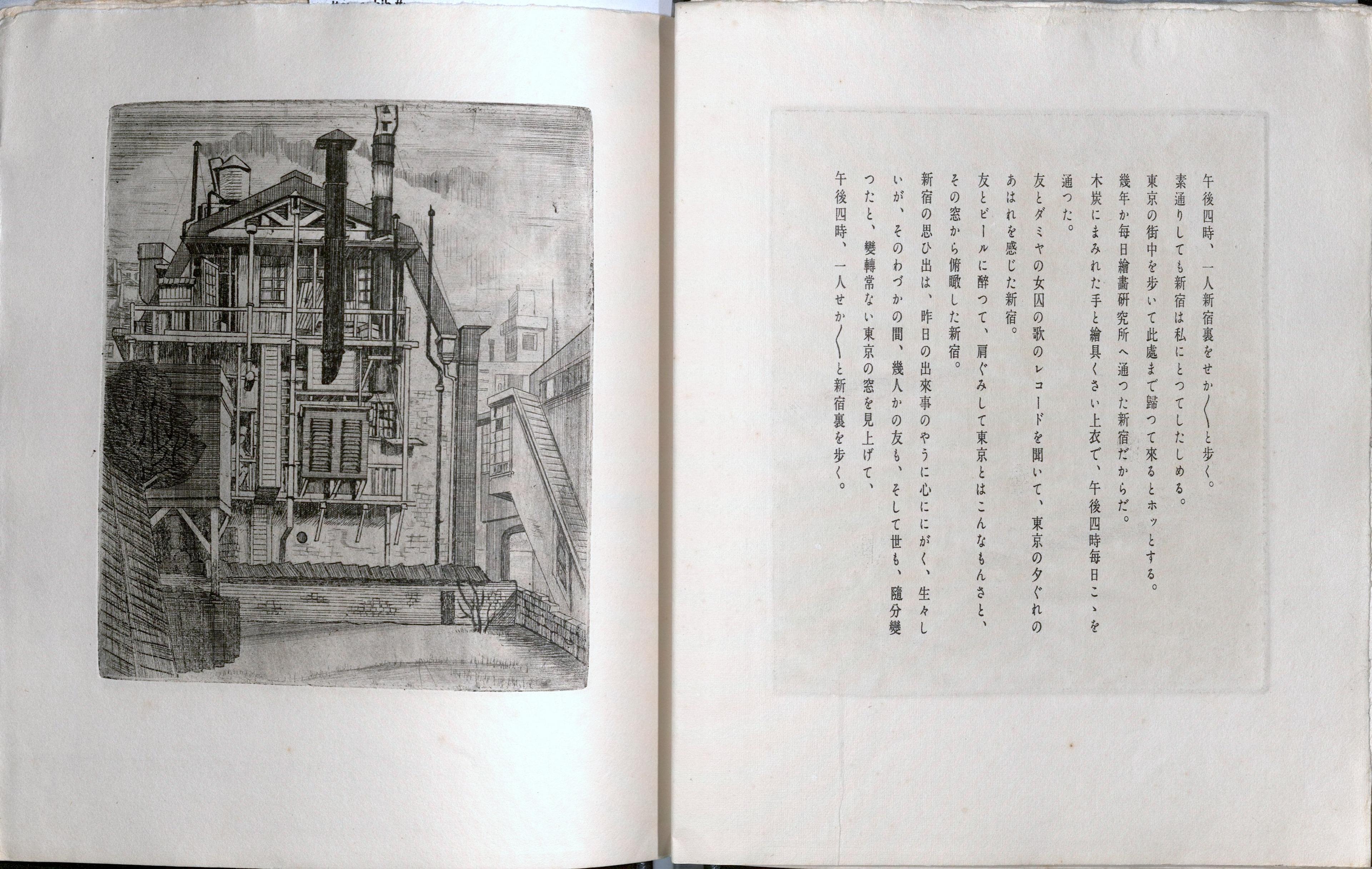

The fifth book in the series, Window to Tokyo (東京の窓, Tokyo no Mado, 1942) by Sekino Jun'ichirō (関野凖一郎, 1914–1988), adopts a more peaceful theme, capturing quiet, everyday scenes of Tokyo rather than the militarized, nationalistic atmosphere. Ten copperplate etchings show scenes, often through a window, around Tokyo. Each etching is accompanied by poems written by Sekino Jun'ichirō, reflecting his personal observations of the city. The artist’s playful use of light in these scenes imparts a Turneresque impression, inviting viewers into a dreamy, atmospheric vision of Tokyo that contrasts with the prevailing wartime tone.

Window to Tokyo (東京の窓, Tokyo no Mado). (Tokyo: Aoi Shobo, 1942)

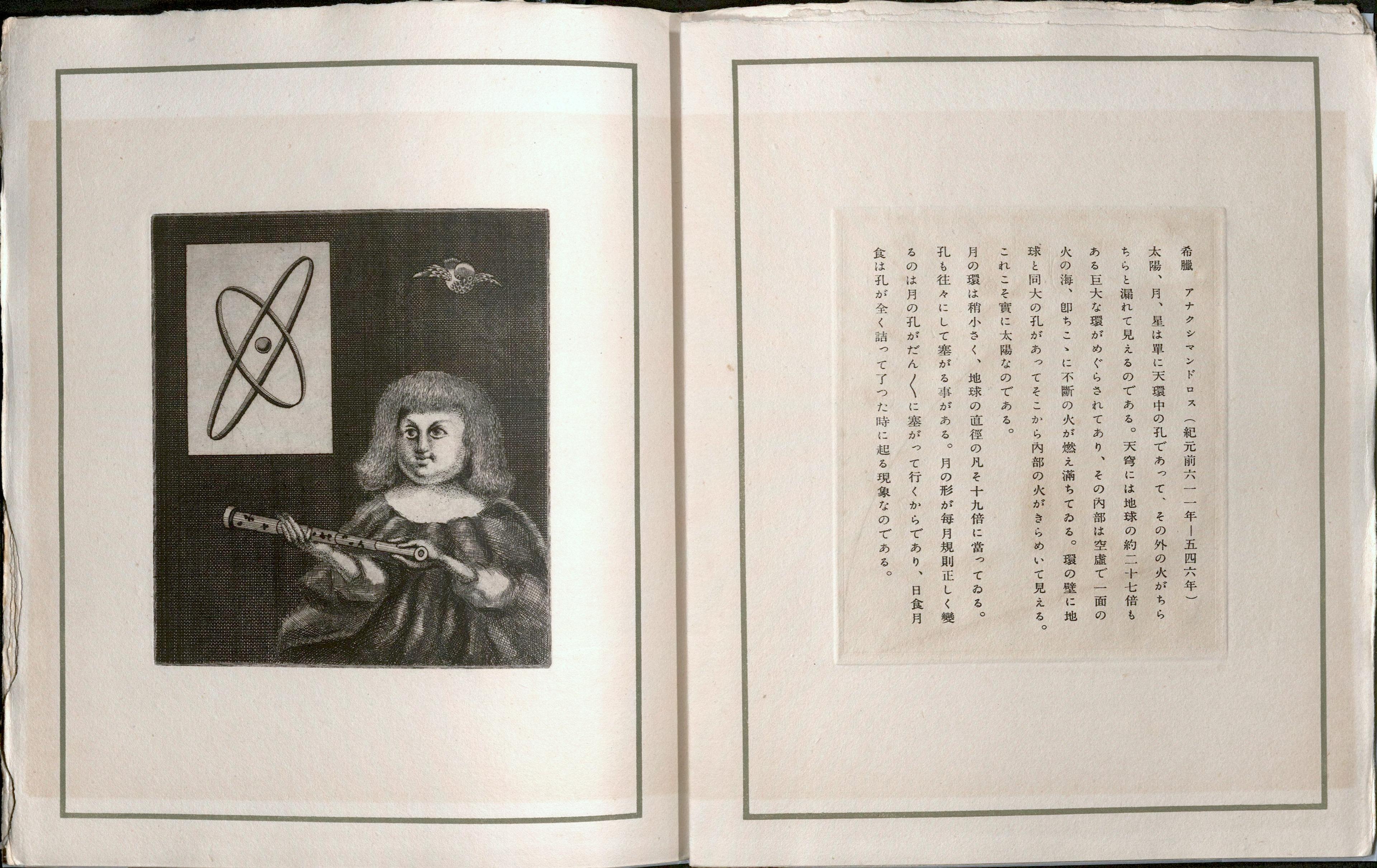

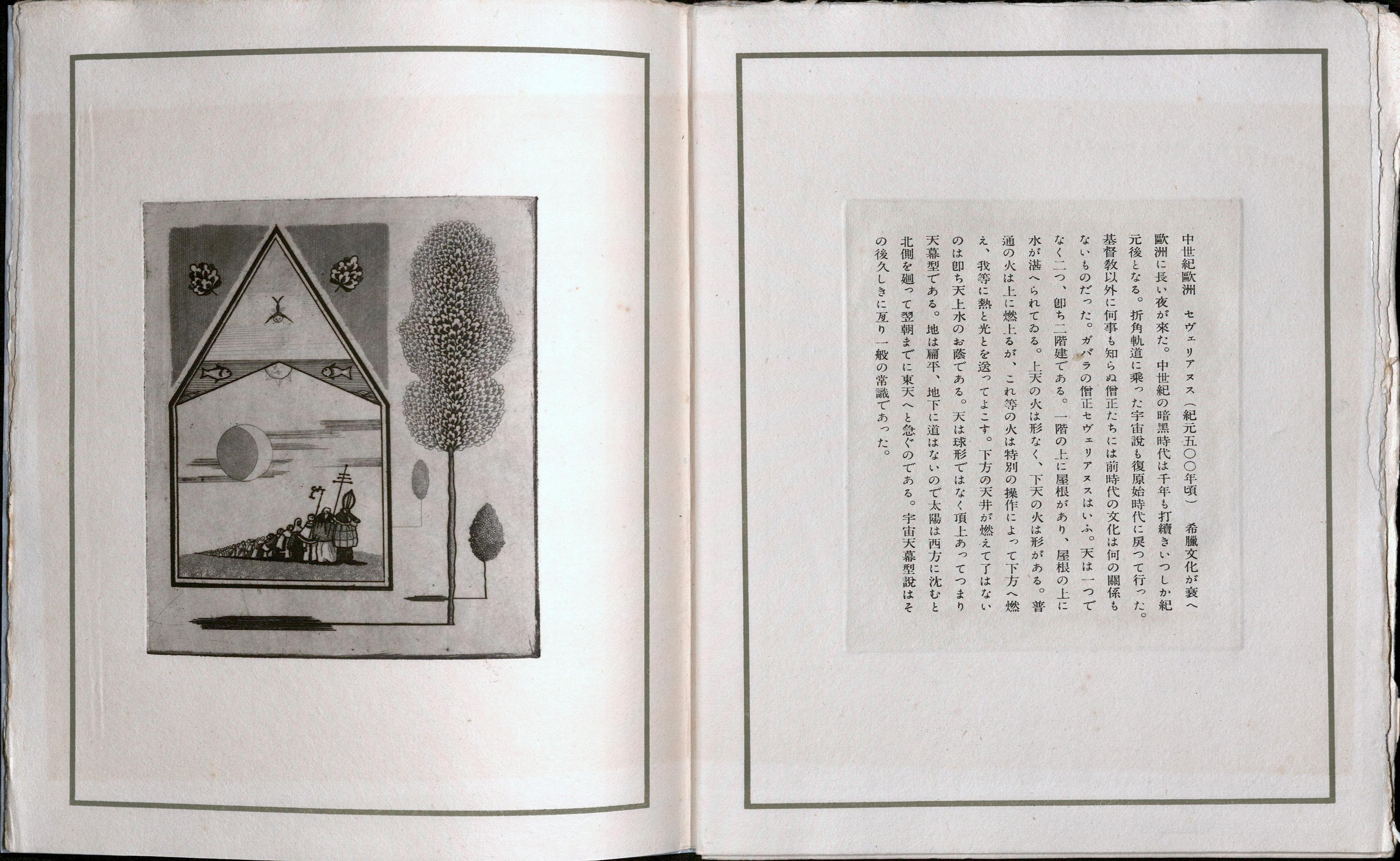

The sixth book, Story of the Ancient Universe (宇宙說, Uchu setsu) by Takeo Takei (武井武雄, 1894–1983), offers images and text on the origin of life and the establishment of ancient civilizations. The following selection is a tribute to Greek culture.

Story of the Ancient Universe (宇宙說, Uchu setsu). (Tokyo: Aoi Shobo, 1943)

Taken as a whole, the collection of nine print portfolios expresses the diversity of Japanese printmaking, featuring a wide array of techniques and themes that provide insight into Japanese art during World War II. While most sets of this rare publication are composed of portfolios from multiple editions, those in Watson Library’s copy are all from the same edition, number 82 of 250 (though it is unlikely that 250 copies were actually printed). This set enriches Watson Library’s collection on modern Japanese art and provides another valuable resource for scholars, students, and other researchers.

See additional selections from the nine portfolios

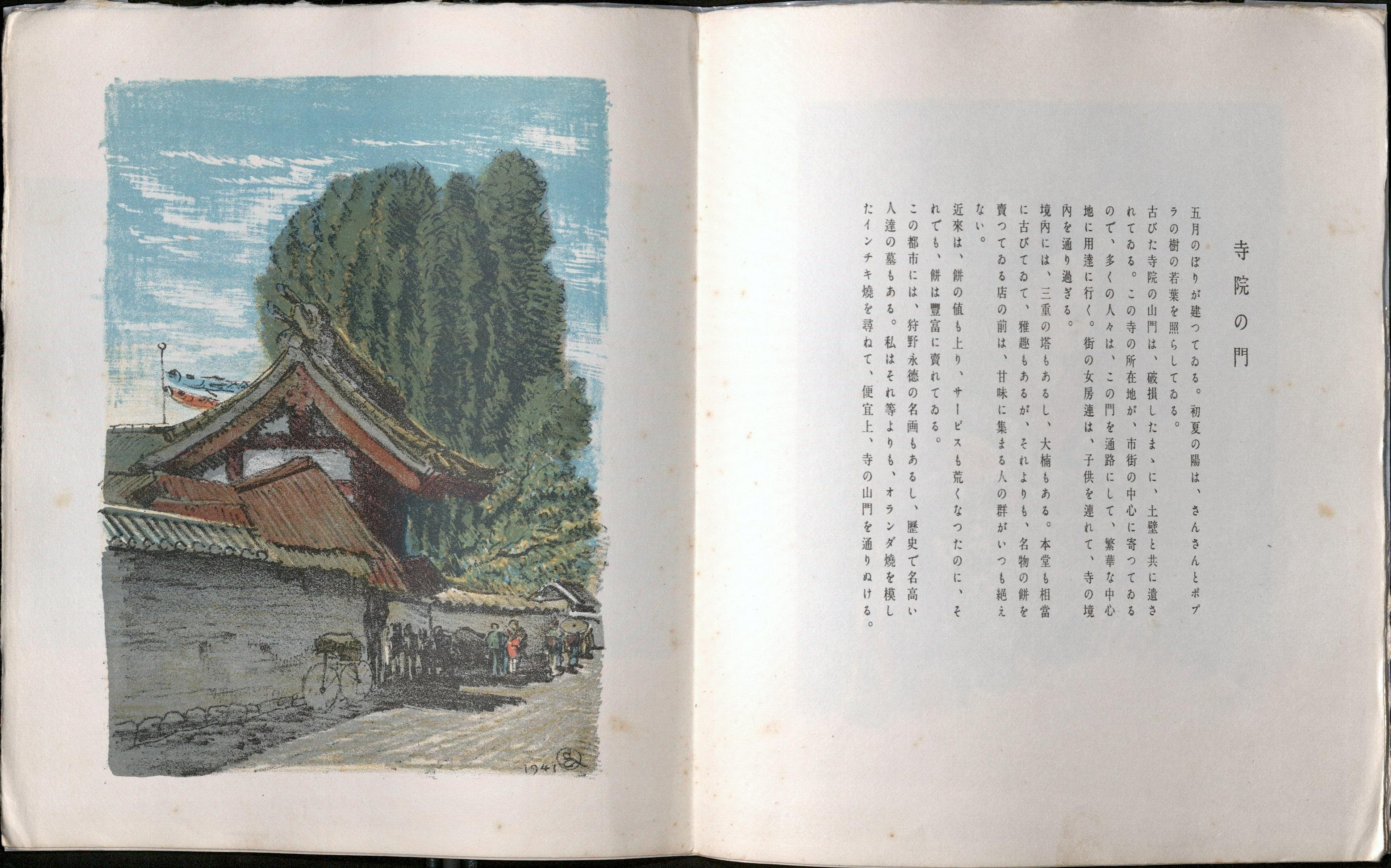

Ten lithograph illustrations with colorful and calming depictions of urban life in Japan. Oda Kazuma (織田一磨, 1882–1956). Life in the City (都會生活, Tokai seikatsu). (Tokyo: Aoi Shobo, September 30, 1941)

Ten woodblock-printed illustrations depicting the bustling life in and around harbor. Kawanishi Hide (川西英, 1894–1965). Harbour Scenes (港都情景, Koto jokei). (Tokyo: Aoi Shobo, December 15, 1941)

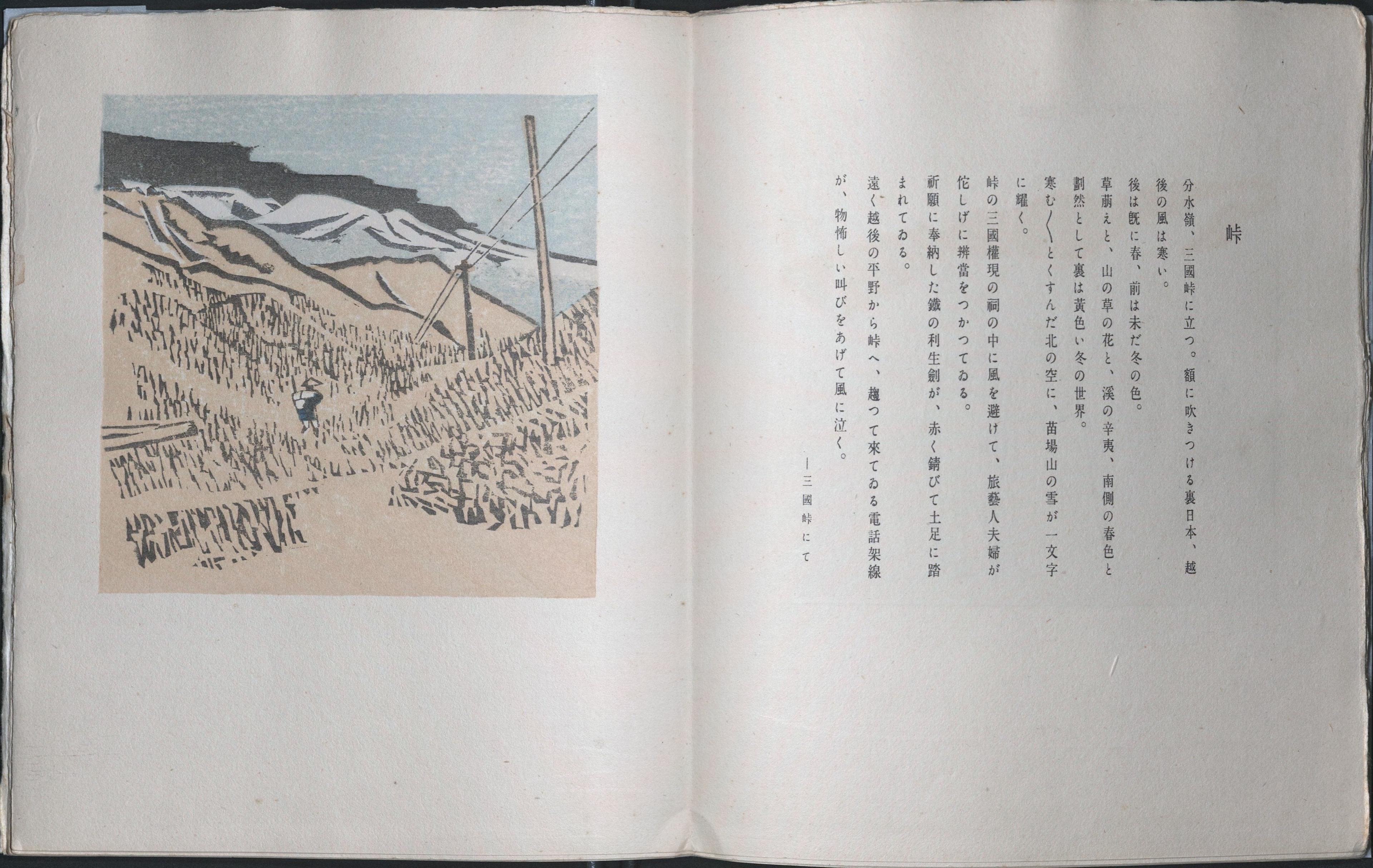

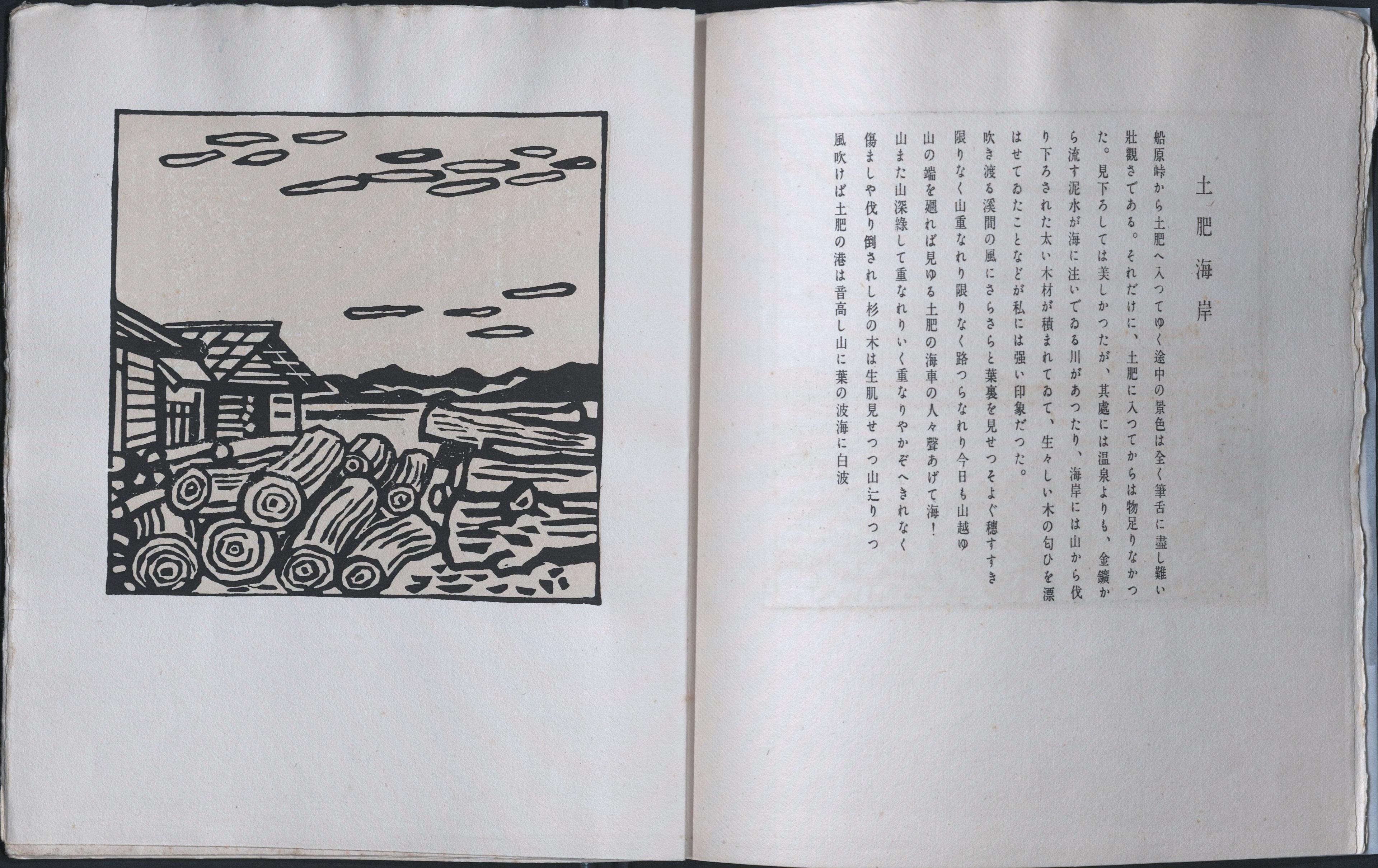

Ten woodblock-printed illustrations showcasing scenes of rural landscapes and country life in Japan. Sempan Maekawa (前川千帆, 1888–1960). New Sketches of the Field (新野外小品, Shin Yagai Shohin). (Tokyo: Aoi Shobo, July 25, 1942)

Ten copper-plate etchings on the origin of the universe and a study of ancient civilizations. Takeo Takei (武井武雄1894–1983). Story of the Ancient Universe (宇宙說, Uchu setsu). (Tokyo: Aoi Shobo, December 25, 1943)

Ten woodblock-printed colorful illustrations of organisms that one might otherwise neglect in the natural world. Onchi Koshiro (恩地孝四郎, 1891–1955). Insects, Fish, and Shellfish (蟲・魚・介 , Mushi, uo, kai). (Tokyo: Aoi Shobo, March 15, 1943)

Ten woodblock-printed designs depicting naturalistic and texture-rich landscapes from the Izu Peninsula. Hiratsuka Unichi (1895–1997). Pictures and Words on a Circuit of Izu Peninsula (Izu Isshu Shoshi). (Tokyo: Aoi Shobo, March 15, 1943)