Any library article about space planning will have one of four titles:

- In space no one can hear you scream

- Space the final frontier

- I have issues, I need space

- [current year]: A Space (Planning) Odyssey

Sadly, there are no good space-related puns left unused, but we still need to call these articles something. While there has been a library at The Met since it was founded in 1870, the current space reopened as the Thomas J. Watson Library in 1965 after a multi-year expansion and renovation. Since then, even though the Museum has changed around us, the library’s footprint has not.

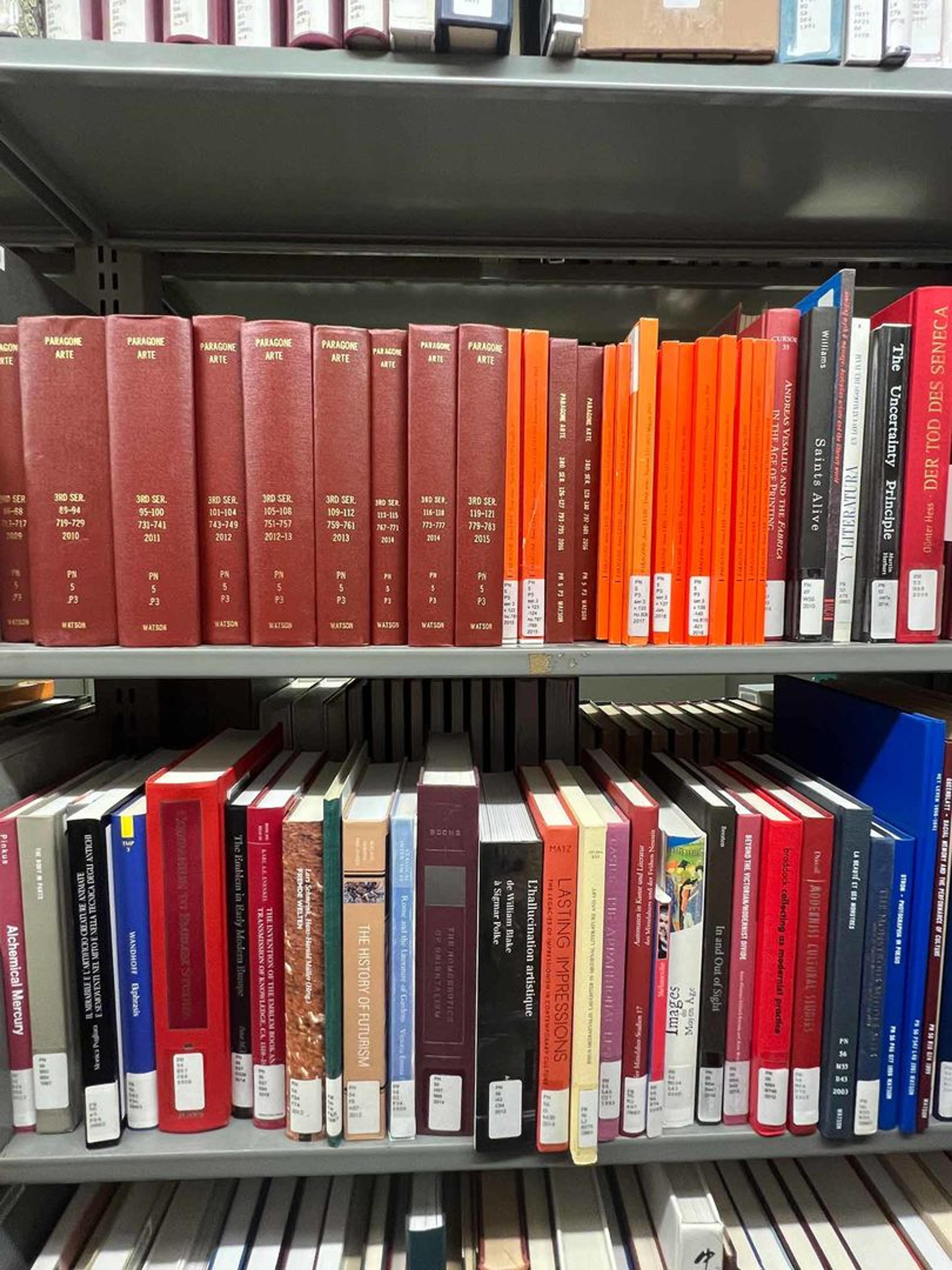

Books being shelved by workers from Clancy-Cullen

This means that our stacks, which were designed to house 270,000 books in 1965, now hold almost three times that number. We make use of offsite storage to house another 380,000 books. How have we managed to continue to operate within these fixed space limits?

See this photo of the beautiful modern exterior during the heartbreakingly brief period where our reading room had Central Park views.

Our stacks consist of two levels below the main Reading Room, which is accessed by an elevator, a variety of stairs, and a mechanical dumbwaiter if you are small enough to fit in it. The differing classification systems in the stacks by which the books are shelved is a palimpsest of the history of library science. The original home-grown Metropolitan Museum of Art (MMA) classification, which followed the familiar pattern of the Dewey Decimal System but with expanded areas for art, was employed until 2002, when we adopted the Library of Congress Classification System (LC) more familiar in American academic and research libraries.

We stopped adding books using the MMA Classification System and hired Clancy-Cullen—a relocation and logistics company that works with many libraries—to compact that area and add growth space to the quickly growing LC Classification section. This was also the first major group of materials sent to offsite storage at Clancy’s facility in Patterson, New York. At the time this gave us enough growth space for about nine years of growth.

Growth space is calculated using the highly technological method of the string measure. A team of two people uses a piece of string and a clipboard. One person measures along each empty space on the shelf and calls out “mark” each time they reach the end of the string, while the person with the clipboard makes the mark. When they reach the end of a section, they tally the marks and multiply by the length of the string. Then you have a relatively quick and accurate measure of the actual empty space on shelves.

String measuring a shelf

After this first big shift with Clancy in 2010, we had approximately 8,540 feet of growth space out of 33,000 total linear feet of shelf space in the regular stacks. By 2019, Watson Library was at 89% full, with only 11% growth space. The industry standard for completely full is 88% full—above that, you have to physically shift books every time you go to shelve a new book, and the entire process becomes unworkably inefficient.

However, in 2020, as we were attempting to get our finances together for another big shift to spread out our growth space, COVID–19 shut us down. It also impacted the Museum’s finances, resulting in drastic budget cuts and across-the-board layoffs. The lack of space in the stacks seemed less important by comparison, but was still a major problem as we worked with reduced staff to operate the library as normally as possible. Our other option, sending all new acquisitions offsite, was also out of the question since that budget was frozen as well. What to do?

Size-based Shelving

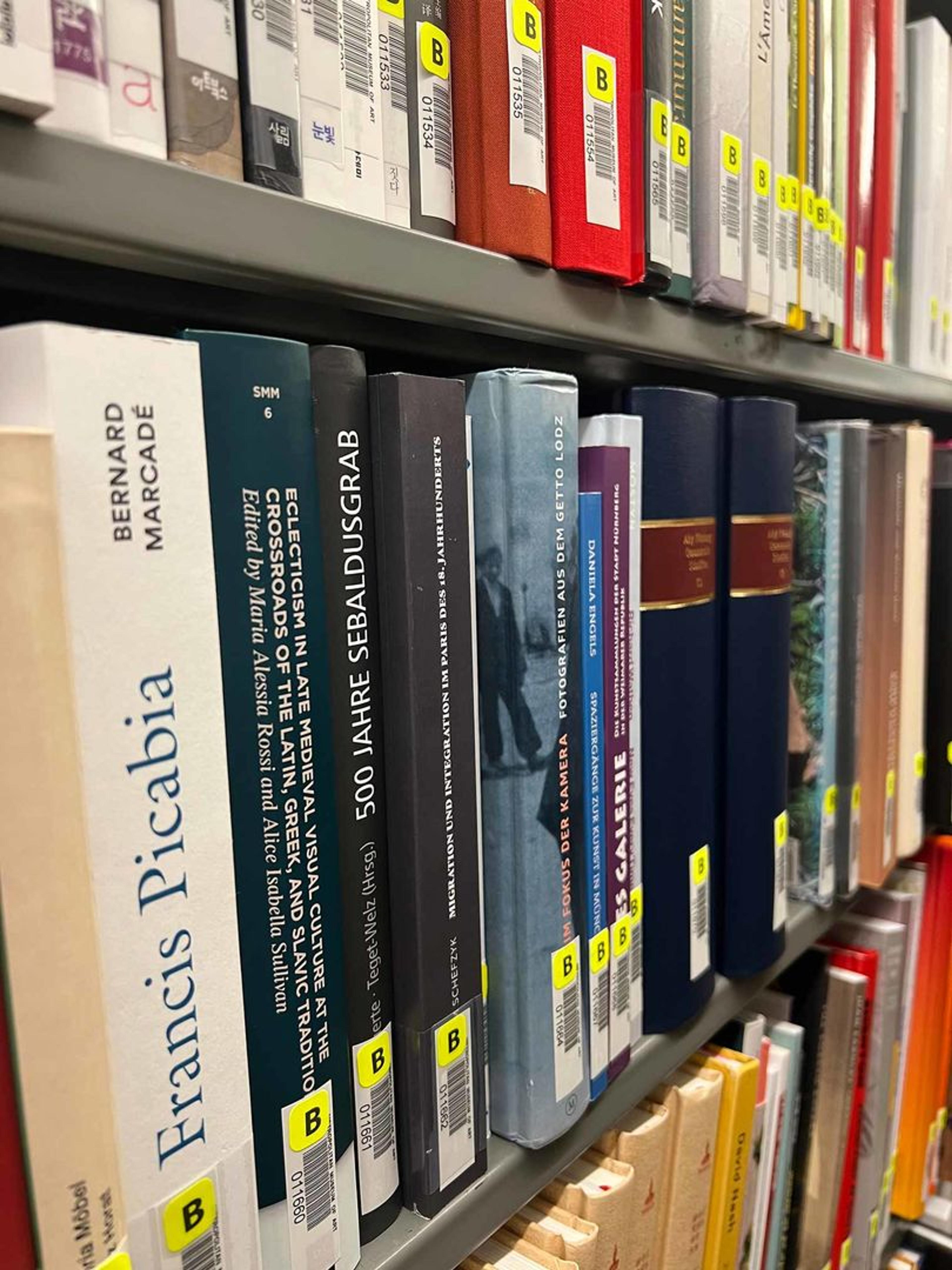

The pandemic closure proved to be the perfect opportunity to implement a new, more efficient shelving system based on size. Previously, there were six shelves to a bay to accommodate a range of book heights. However, this resulted in a lot of unused space to fit the outliers.

Look at all that wasted space in the old shelving system. In NYC, you could rent that out as a studio apartment.

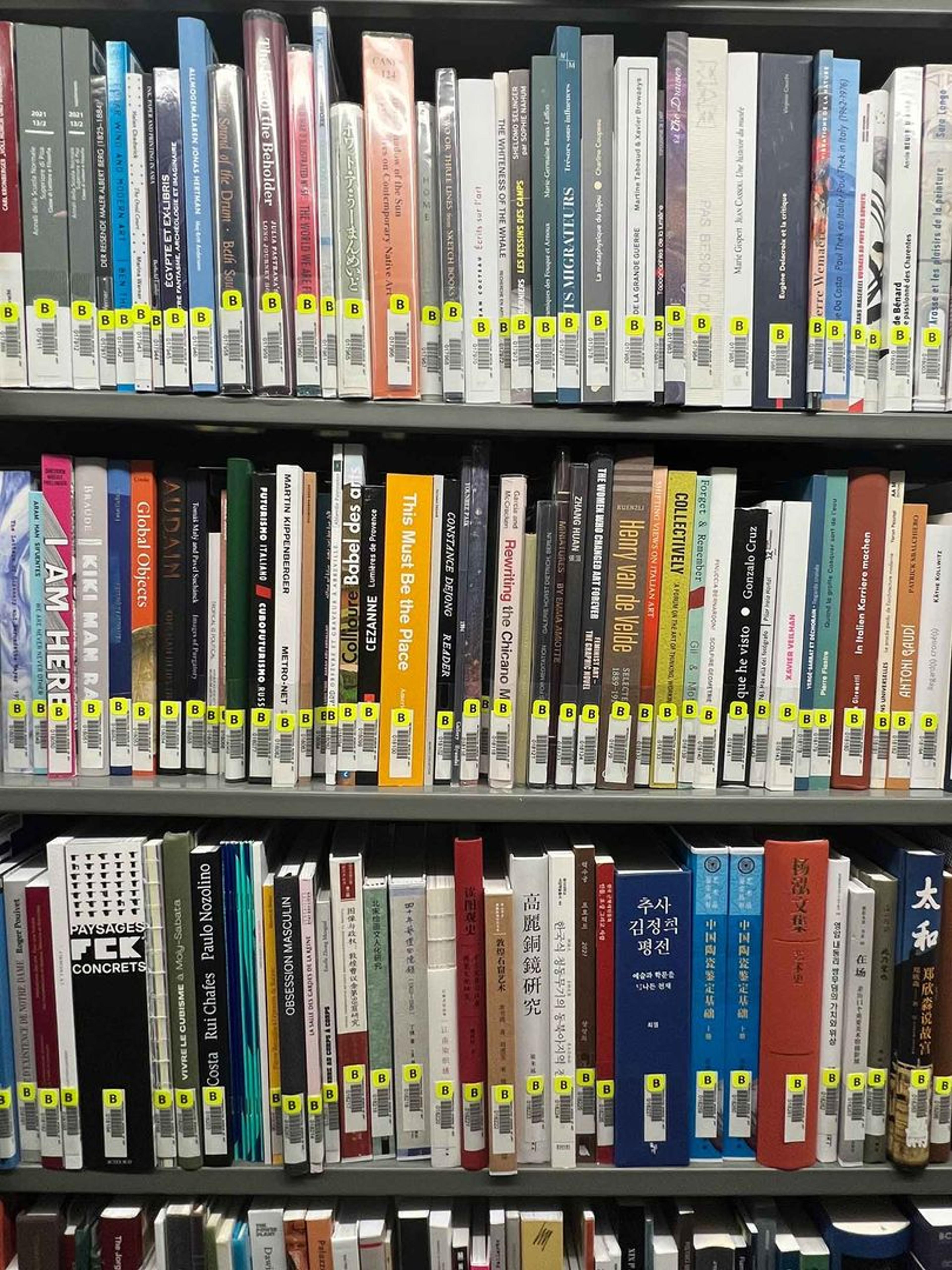

We realized that dividing books up by size would allow us to immediately add a good deal of growth space. In addition, by adding books to the shelves in the order they are received, we would be able to keep all the growth space together instead of spread out, so we would easily see how quickly we were using it up. It would also make shelving books simpler for our Circulation technicians. Shelves of new books are simply placed after the last books in each size section, rather than having to interfile them across the entire stacks, reducing the time to shelve a truck of books from an hour to a few minutes. In our new designations, which divide bays up into ten, eight, six, five, and four shelves, we find that approximately a third of the books formerly shelved in six-per-bay shelves fall in the eight-per-bay size, which gives us a 33% increase in shelving for a large chunk of the collection.

By eliminating the wasted vertical space, we have created more shelving, although less housing for the tight NYC rental market.

SIBS call numbers have their size designation followed by sequential numbers in accession order. This results in a different type of serendipity as seemingly unrelated books live next to each other, like listening to an iPod on shuffle.

After trying this as a pilot project, the many upsides outweighed the downsides, and we adopted SIBS (Size-Based Shelving) for all incoming books. The upsides were the efficiency in terms of space used, the ease of maintaining and tracking growth space, and the ease of shelving new accessions. The downside was the lack of browsing serendipity from shelving by subject. However, Watson Library is not a browsing library. Few patrons have access to the stacks and we already store a significant percentage of our collection offsite.

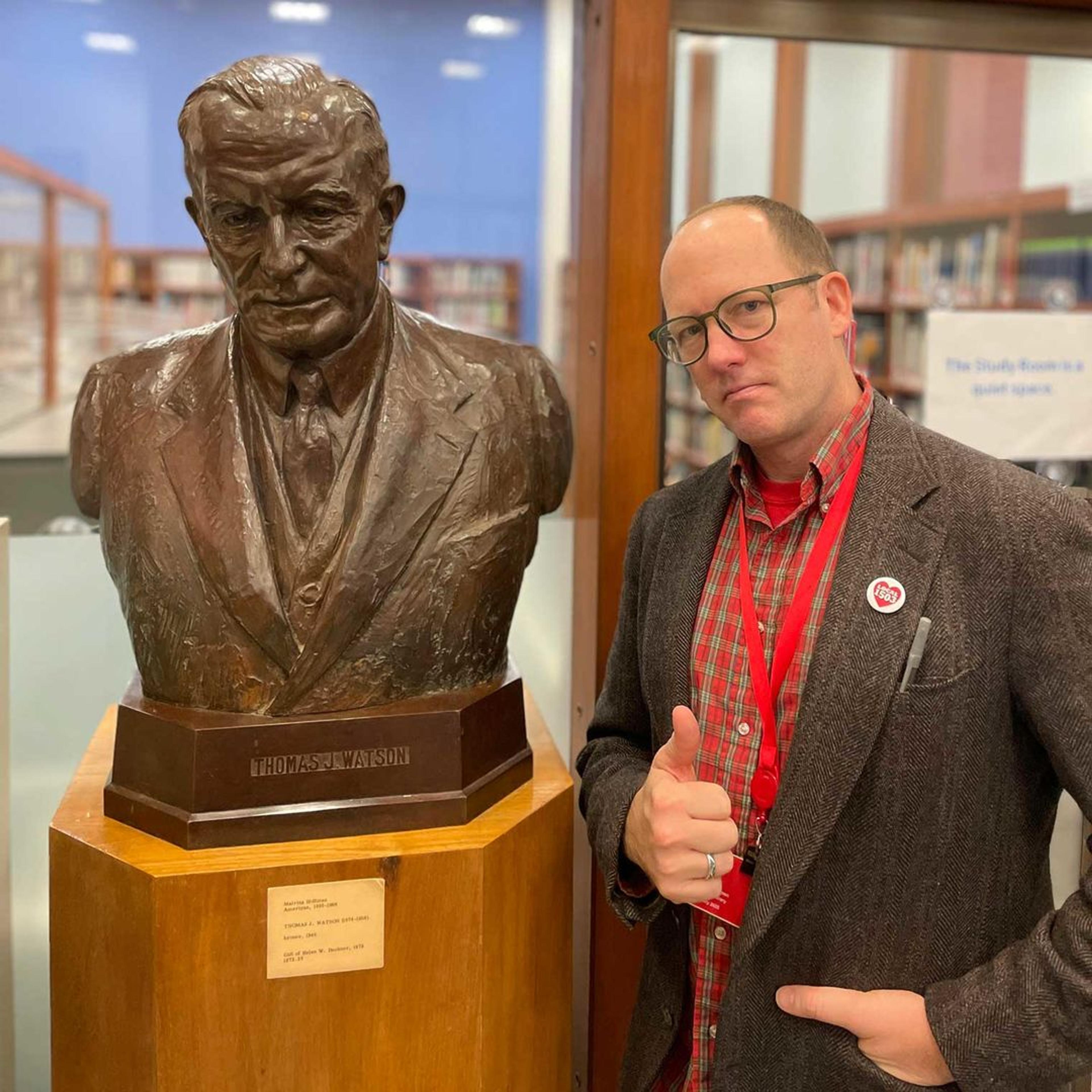

We’ll continue to add new books in SIBS,and gradually convert the older books to SIBS or send them offsite as appropriate. Given the size of our collection, it means job security for several lifetimes. Considering the extreme space constraints we face, the choice between continuing to expand our collection for the future or ceasing to acquire new research materials seemed like an easy call. It’s a radical departure from traditional library approaches to shelving books, but when it comes to radical approaches, we like to think Thomas J. Watson would approve.

The author with a bust of Thomas J. Watson—if he had thumbs we know he'd give us a thumbs up.