Fig. 1. El Castillo, Chichen Itza, Yucatan, Mexico. Photo by the author

«Designated a UNESCO world heritage site in 1988, the pre-Hispanic city of Chichen Itza, Mexico, currently receives over two million visitors per year (fig. 1). The city itself was settled in the Early Classic Period (ca. A.D. 250–550), reaching its peak of population and architectural constructions in the Late and Terminal Classic Periods (ca. A.D. 650–1000).»

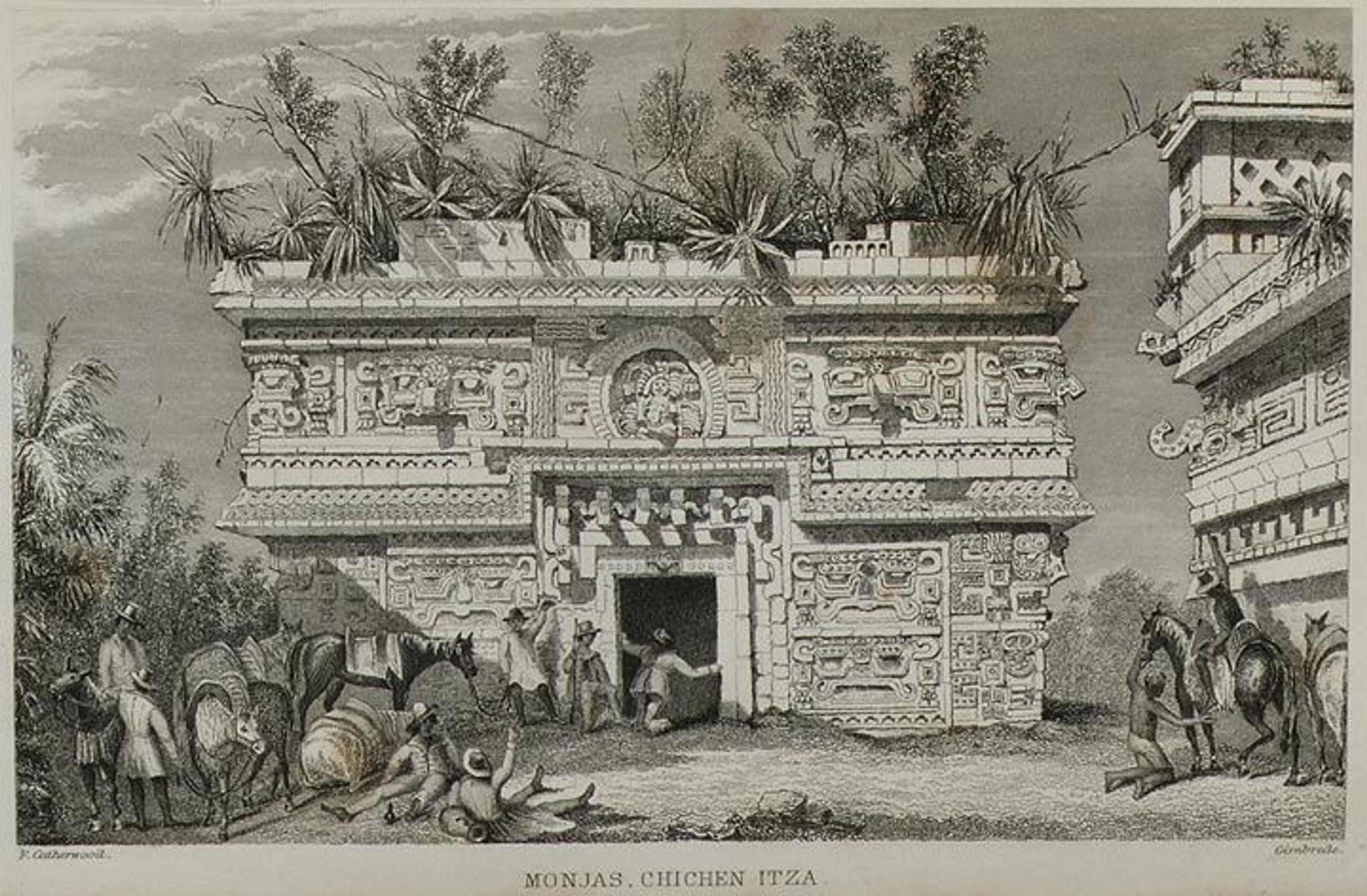

The site captured the imagination of the wider public in the 19th century after John Lloyd Stephens and Frederic Catherwood published their account of travels through Yucatan (fig. 2a), which led early photographers such as Désiré Charnay (fig. 2b) and Augustus and Alice Dixon Le Plongeon to Mexico to document the city. Explorers Teobert Maler and Alfred Maudslay recorded the architecture and inscriptions, but not until Edward H. Thompson purchased the land around the site in the late 19th century did archaeological explorations begin in earnest. Thompson dredged the Sacred Cenote—a water-filled sinkhole used for religious ceremonies and offerings that had served as a pilgrimage destination for centuries—and shipped the artifacts to the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University.

Fig. 2a. John Lloyd Stephens (American, 1805–1852). "Monjas, Chichen Itza" from Incidents of Travel in Yucatan, 1843. New York: Harper Bros. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of the Department of Twentieth-Century Art, 1998 (UD S83 1843 v.2)

Fig. 2b. Désiré Charnay (French, 1828–1915). La Prison, à Chichen-Itza, 1857–89. Albumen silver print from glass negative; 33.3 x 42.4 cm (13 1/8 x 16 11/16 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gilman Collection, Purchase, Jennifer and Joseph Duke Gift, 2005 (2005.100.565)

The Mexican government and the Carnegie Institution excavated and restored buildings beginning in the 1920s. In 1926, as part of the Carnegie Institution project, archaeologist George Vaillant excavated in the earliest part of the city, known as Old Chichen, in a group of buildings decorated with architectural sculpture. One of these buildings was a small, south-facing temple (Structure 5C3) nicknamed the Casa de Cabecitas (House of the Small Heads).

Fig. 3. Head of a rain god, 10th–11th century. Mexico, Mesoamerica, Yucatan. Maya. Fossiliferous limestone; H. 13 3/4 x W. 11 7/8 x D. 9 3/8 in. (34.9 x 30.2 x 23.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Gift of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1963 (1978.412.24)

A limestone head in The Met collection (fig. 3) recovered by Vaillant was the finest of many pieces of sculpture found within the temple chamber; other notable artifacts included two intact Atlantean figures that once supported the lintel of the entryway. This head, now detached, likely belonged to an architectural sculpture in high relief as part of a facade or as a free-standing monument. The fact that excavators did not find the body associated with this head may indicate that former inhabitants of the city had removed the head from its original location and revered it enough to place it in the small temple.

This monumental head, carved from limestone, depicts a supernatural being, as defined by its skeletal features and the presence of large earflares and a beaded headband. The subject's long hair is held back, which is indicated by deep incisions flowing down the reverse side of the head. A circular boss dominates the forehead, probably representing a round jewel hanging down from the headband.

The Maya perceived deities such as the one depicted here to have a different type of vision than humans, which artists indicated through their presentation of these subjects' eyes. Framed by heavy brows and under-eye lines that terminate in scrolled shapes, the sculpture's prominent eyes have an incised spiral-shaped pupil with traces of red pigment. Combined with the raised dots on the cheeks on either side of the nose, these pupils are markers of godliness in Maya art. The fleshless jaw contains a row of straight, squared teeth, and two scrolls emerge from either side of the mouth. There is notable damage to the nose, the loss of which may have occurred over the course of its use in antiquity.

Fig. 4. Mexican museum collections hold several sculptures similar to The Met's example. Seen here are comparative sculptures from the Gran Museo del Mundo Maya, Mérida (left) and the Museo Regional de Antropología de Yucatán, Palacio Cantón, Mérida (right). Photos by the author

Maya artists often depicted supernatural entities with a mixture of signifiers attributed to multiple deities, an artistic approach that complicates efforts to identify these subjects according to the particular divine attributes of the culture's pantheon. While most of the depicted features seen in The Met's sculpture—the skeletal jaw, scrolls emitting from the mouth, earflares, god eyes with spiral pupils, and long hair—associate this image with the rain deity known as Chahk, the under-eye scrolls could also indicate that the artists infused this rain deity with an aspect of the Sun God, whose eyes are often adorned with such motifs.

The sculpture of the deity face also reflects facets of several different stylistic approaches, one of the hallmarks of art from Chichen Itza. Scholars commonly interpret the blurring of styles as evidence of interaction between the Maya at Chichen Itza and their contemporaries, the Toltecs of Central Mexico, during the Early Postclassic Period (ca. A.D. 1000–1200). Regardless of its precise identification, this representation was a supernatural portrait meant to draw the viewers' attention to the mercurial natural phenomena personified in the subject's fearsome face.

Reference

Vaillant, George C. "1952 Report of George C. Vaillant on the Excavations at Station No. 13 [1926]." In Chichen Itza: Architectural Notes and Plans, by Karl Ruppert, 157–162 and fig. 145b. Washington: Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1952.

Related Links

Now at The Met: "'The Blood Was Pooled, the Skulls Were Piled': Maya Star Wars and a Misconstrued Doomsday" (May 29, 2015)

Now at The Met: "Sacrifice, Fealty, and a Sculptor's Signature on a Maya Relief" (March 19, 2015)