Fig. 1. Ceremonial handle, 7th–9th century. Mexico or Guatemala, Mesoamerica. Maya. Jade (jadeite/omphacite); H. 5 1/2 x 1 1/8 x 1 3/4 in. (14 x 2.8 x 4.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979 (1979.206.1132)

«Ancient Maya kings and queens were masters of political pageantry. Rulers and nobles engaged in ritual celebrations while wearing elaborate costumes and regalia that incorporated images of both ancestors and deities. One of the most important classes of objects shown in royal portraits and found in royal burials is that of the scepter, a handheld staff often made of stone. The Metropolitan Museum's collection contains a fragment of one such object made of greenstone (fig. 1).»

The most common type of scepter known from the Classic Maya period (ca. a.d. 250–900) is the "eccentric flint," an astounding feat of stone knapping that created a flashy, fractal-like ceremonial blade from a chert biface (fig. 2). The eccentric flints would have been hafted on a wooden handle for use in a procession or ritual dance. The human-like and supernatural profiles show a variety of characters, but most relate back to a Maya god known as K'awiil, the god of lightning. The most recognizable feature of K'awiil is his tall, prominent forehead, decorated with a pill-shaped cartouche pierced by either a jade celt, a torch, or a tobacco cigar, from which emerges plumes of smoke. He has a human-like body and a zoomorphic head that consists of an upturned snout, large eyes with a spiral pupil, and one or both of his legs often morph into a serpent. The meaning of the serpent leg is not immediately clear, although all across ancient Mesoamerica, lightning was associated with snakes.

Fig. 2. Eccentric flint scepters. Left: Scepter with profile figures, 7th—8th century. Guatemala, Mesoamerica. Maya. Flint; H. 13 5/8 x W. 7 1/2 x D. 5/8 in. (34.6 x 19.1 x 1.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Purchase, Nelson A. Rockefeller Gift, 1967 (1978.412.195). Center: Eccentric flint with profiles of K'awiil, the lightning god, A.D. 600–800. Belize, Guatemala, or Mexico. Late Classic, Maya. Chert; H. 33.3 cm, W. 15.0 cm, D. 1.1 cm (13 1/8 x 5 7/8 x 7/16 in.). The Princeton University Art Museum, Gift of Shelby White in honor of Gillett G. Griffin (2003-292). Right: Eccentric flint, 600–700 CE. Maya, Late Classic. Flint; 24.13 cm x 13.02 cm x 1 cm (9 1/2 in. x 5 1/8 in. x 3/8 in.). Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection (PC.B.587)

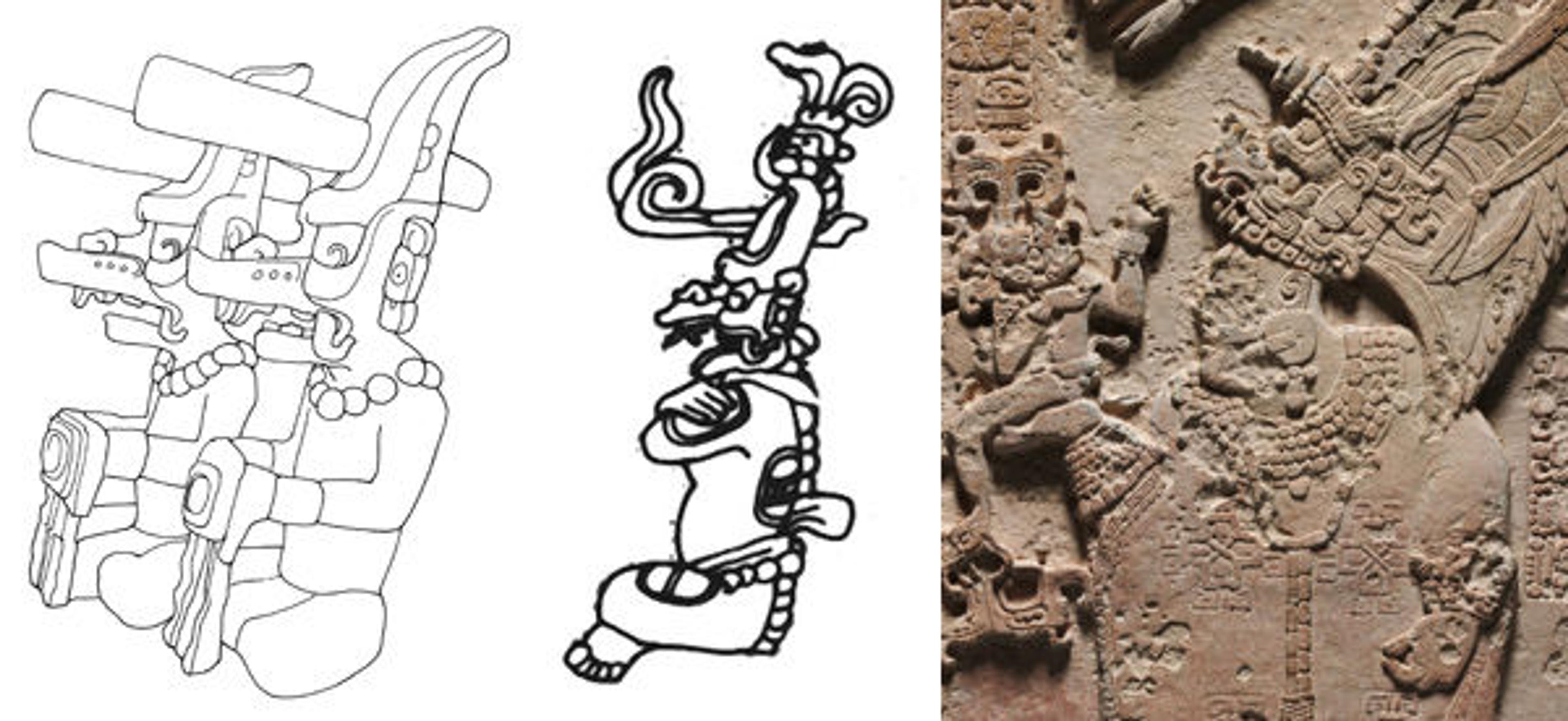

Maya artists during the Classic period portrayed the K'awiil scepter not as a stone object, but as an animate participant in the rituals depicted (fig. 3). The small-scale god flails about, sits in a solemn pose with crossed arms, gestures to the viewer of the scepter, or even holds other objects himself. K'awiil is particularly associated with accession rites, and scribes commemorated one's ascension to the throne using the metaphor for "conjuring" the god K'awiil. The first conjuring of K'awiil in a ceremony was presumably reenacted as the new kings and queens grasped the stone scepters.

Fig. 3. Depictions of K'awiil. Left: Stucco-covered wood sculptures from Tikal Burial 195. Drawing by Linda Schele. Center: Panel from Temple XIV. Detail of drawing by Linda Schele. Right: Panel with royal woman (detail), ca. A.D. 795. Mexico or Guatemala. Maya. Limestone; H: 60.40, W: 69.80 cm (23 3/4 x 27 7/16 in.). The Cleveland Museum of Art, Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund (1962.32)

The Met's jade fragment probably represents the lower portion of a K'awiil scepter, portraying his lower legs and serpent foot (fig. 4). Analysis of the stone classifies it as omphacitic jadeitite—a hard mineral composed of silicon, aluminum, calcium, iron, and magnesium, with which the sculptor could add a curvy profile to the lower leg in order to subtly create a sense of tactile flesh. The scepter terminates in the head of a serpent with round eyeballs, an open mouth with fangs, an upturned snout, and distinct eyebrows. Tiny biconical drill holes along the serpent's lower jaw would have allowed for beads or other danglers to be attached in order to make loud sounds as the ruler employed the scepter in motion.

Very few sculptures of K'awiil in the round have survived, as they were probably made out of wood or other perishable materials (as in fig. 3, left). This characteristic makes the possible K'awiil foot rare and important for understanding Late Classic Maya regalia as depicted in relief carvings and painted vessels. Just as with the eccentric flint scepters, rulers would have commissioned this jade object to embody the god of lightning as they performed in front of nobles and courtiers.

Fig. 4. A hypothetical reconstruction of the Met's K'awiil scepter, based on plate 72 in Lords of Creation: The Origins of Sacred Maya Kingship by Virginia Fields and Dorie Reents-Budet.

Resources and Additional Reading

Fields, Virginia, and Dorie Reents-Budet. Lords of Creation: The Origins of Sacred Maya Kingship. Los Angeles: Scala, 2005.

Miller, Mary, and Simon Martin. Courtly Art of the Ancient Maya. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2004.

Schele, Linda, and Mary Ellen Miller. The Blood of Kings: Dynasty and Ritual in Maya Art. Fort Worth: Kimbell Art Museum, 1984.

Stone, Andrea, and Marc Zender. Reading Maya Art: A Hieroglyphic Guide to Ancient Maya Painting and Sculpture. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2011.