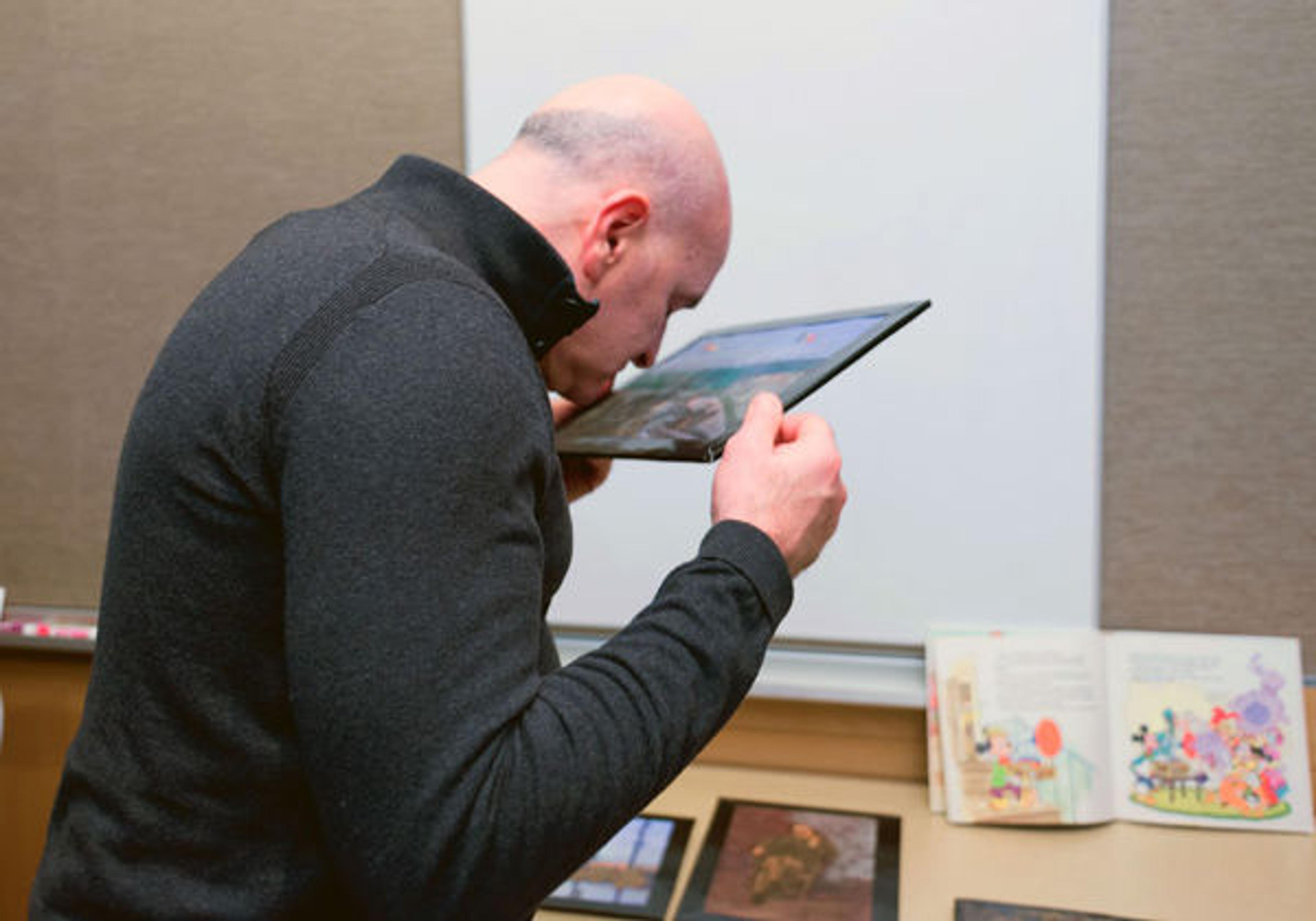

A visitor smelling a scratch-and-sniff painting at the spring 2015 MediaLab Expo. Image courtesy of the author

From Don Undeen, Senior Manager of MediaLab:

The MediaLab has been fortunate enough to work frequently with the Met's fantastic Access Programs and Community Programs Office in exploring ways that museums can be more welcoming to visitors of diverse abilities. One of the concepts we've been learning about is universal design, which is the idea that products and experiences should be constructed to be usable by a wide range of people regardless of disability, age, or background. A corollary to this is that when you design for accessibility you generally end up producing results that benefit everyone. After a discussion about how to make the museum experience available to blind and partially sighted visitors, Ezgi created a suite of products that can bring anyone closer to the Met's collection.

Multisensory Museum Experience

«In the majority of museums, visitors can only experience the artworks by viewing them. Most museums work to make sure that galleries have neutral smells and sounds so that the visitor can focus on the artworks, but those factors can alter the experience significantly. All of the senses—sight, sound, touch, smell, and hearing—are a part of the museum experience.»

Multisensory Met, a series of activities designed to create a more fulfilling museum experience, in the spring 2015 MediaLab Expo. Image courtesy of the author

In order to protect the artworks, visitors are strictly forbidden from having any physical contact with the art. This inspired me to create Multisensory Met, a series of activities designed to provide a museum experience that makes use of all the senses. I believe that creating a multisensory environment will truly enhance the museum experience.

Multisensory Booklet

I initially thought of making a multisensory booklet for visitors to carry around as they view the art. The booklet would feature pictures of artworks in the Met's collection that are equipped with touch-activated sounds and smells so that the visitor can view each artwork and interact with the corresponding activity in the booklet.

A video of Claude Monet's Garden at Sainte-Adresse in the Multisensory Booklet. Video courtesy of the author

Multisensory Sculptures

I think everyone has had the urge to touch, smell, or taste at least one of the Museum's objects. I was immediately fascinated by the beautiful figures in the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas galleries, and I found myself particularly interested in the Power Figure (Nkisi N'Kondi: Mangaaka). I wanted to touch and smell it mainly because of the variety of materials it includes (wood, metal, resin, and shell) and the materials that were added to the figure during rituals, like dirt from burial sites; white clay from riverbeds; and nails, blades, and other hardware.

Power Figure (Nkisi N'Kondi: Mangaaka), 19th century. Republic of the Congo or Cabinda, Angola, Chiloango River region. Kongo peoples; Yombe group. Wood, paint, metal, resin, ceramic; H. 46 1/2 in. (118 cm), W. 19 1/2 in. (49.5 cm), D. 15 1/2 in. (39.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace, Drs. Daniel and Marian Malcolm, Laura G. and James J. Ross, Jeffrey B. Soref, The Robert T. Wall Family, Dr. and Mrs. Sidney G. Clyman, and Steven Kossak Gifts, 2008 (2008.30)

I decided to create a small, touch-sensitive replica of the figure that would have its own smell and sound. I used clay and nails similar to the materials used to make the sculpture. I then put a little bit of essential oil on the top of the sculpture to simulate the original scent of the object.

Views of the clay replica of the Power Figure (Nkisi N'Kondi: Mangaaka). Images courtesy of the author

I also wired the inside of the sculpture so that it would produce a buzzer sound when touched. I used Arduino tools to create a programmable microcontroller and to play wav. files. The sound helped express and emphasize the power of the figure, which added a lot to the overall interaction and experience.

Video of a user touching the multisensory sculpture. Video courtesy of the author

The goal of creating this sculpture was to give visitors a better understanding of the original use of this figure and figures like it. Even though they can't be a part of an actual Kongo ritual, visitors can touch and smell the sacred object and imagine what it might have been like to experience it.

Material Book

I received some useful feedback on the multisensory sculpture, which was that making a replica is always risky because it never fully represents the actual work. Even if I 3D-printed every object, any small flaw or change of size would make the replica less authentic. So I tweaked the idea by removing the replication process and letting the materials speak for themselves.

Material Book is a booklet that allows users to touch a small amount of materials that are similar to those that the Senufo peoples used to create their figures and sculptures. Since visitors can't see the exact materials used to create the sculptures without taking a very close look, having the materials in front of them is a much easier way to gain an understanding of what it would feel like to touch the artworks.

The Material Book for the Oracle Figure (Kafigeledjo). Image courtesy of the author

I created a page for the Oracle Figure (Kafigeledjo) that included wood, iron, porcupine quills, feathers, and commercially woven fiber. I couldn't include bones and dirt in the page, but I replaced them with clay and homemade Play-Doh.

Oracle Figure (Kafigeledjo), 19th–mid-20th century. Côte d'Ivoire, northern Côte d'Ivoire. Senufo peoples. Wood, iron, bone, porcupine quills, feathers, commercially woven fiber, organic material; H. 32 7/16 x W. 13 x D. 4 1/2 in. (82.5 x 33 x 11.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Raymond Wielgus, 1964 (1978.412.488)

Scratch-and-Sniff Paintings

I then focused on how to make paintings a more interactive experience for the visitor, and I came up with the idea of scratch-and-sniff paintings. Inspired by scratch-and-sniff stickers, which I consider a very simple and effective way to add smell to an object, these paintings are safe for the museum environment because the smell is trapped inside the object until the user activates it.

Some of the scented powders that were used to make scratch-and-sniff paintings. Image courtesy of the author

I created these scratch-and-sniff paintings using powdered fragrances, incense, and spices. I stuck them on different parts of a photograph of a painting using a stamp pad so that different parts of the painting would give off different scents. For example, I used floral, salt water, and spicy-cocoa scents for Claude Monet's Garden at Sainte-Adresse to make all the things in the painting smell how they might in real life.

Claude Monet (French, 1840–1926). Garden at Sainte-Adresse, 1867. Oil on canvas; 38 5/8 x 51 1/8 in. (98.1 x 129.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, special contributions and funds given or bequeathed by friends of the Museum, 1967 (67.241)

Sound Paintings

I later decided to continue experimenting with sound by creating touch-sensitive paintings, and I used another Monet painting, Jean Monet (1867–1913) on His Hobby Horse, as my first prototype.

Claude Monet (French, 1840–1926). Jean Monet (1867–1913) on His Hobby Horse, 1872. Oil on canvas; 23 7/8 x 29 1/4 in. (60.6 x 74.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Sara Lee Corporation, 2000 (2000.195)

I created a switch for each element of the painting using tools similar to those used for the replica of the Power Figure (Nkisi N'Kondi: Mangaaka) so that they would produce a specific sound when touched. The switch is made of two layers of copper sheets: one sheet is connected to the ground and the other to the Arduino's power pin. I divided one of the layers into four pieces, all cut in the shape of the painting's four elements: the horse, the child, the ground, and the bushes. I used four different sounds: an ambient nature sound for the bushes, a child talking, a horse neighing, and the sound of moving carriage wheels. I put resistors, or devices that control the flow of electricity in a circuit, between each piece to differentiate them so that when one of the four elements is pressed, the specific switch is activated and it plays the corresponding sound.

A switch for Jean Monet (1867–1913) on His Hobby Horse, made with copper sheets and resistors. Image courtesy of the author

Conclusion

In my internship in the MediaLab, I had the chance to collaborate with people from many different departments at the Museum and learn about new technologies, and I had access to many resources, including 3D printers and prototyping tools. I was able to use my interests and expertise to create accessibility solutions and a more engaging and welcoming museum experience. Multisensory Met started out as an idea based on my interest in creating multisensory experiences and became a new possibility for the Museum.