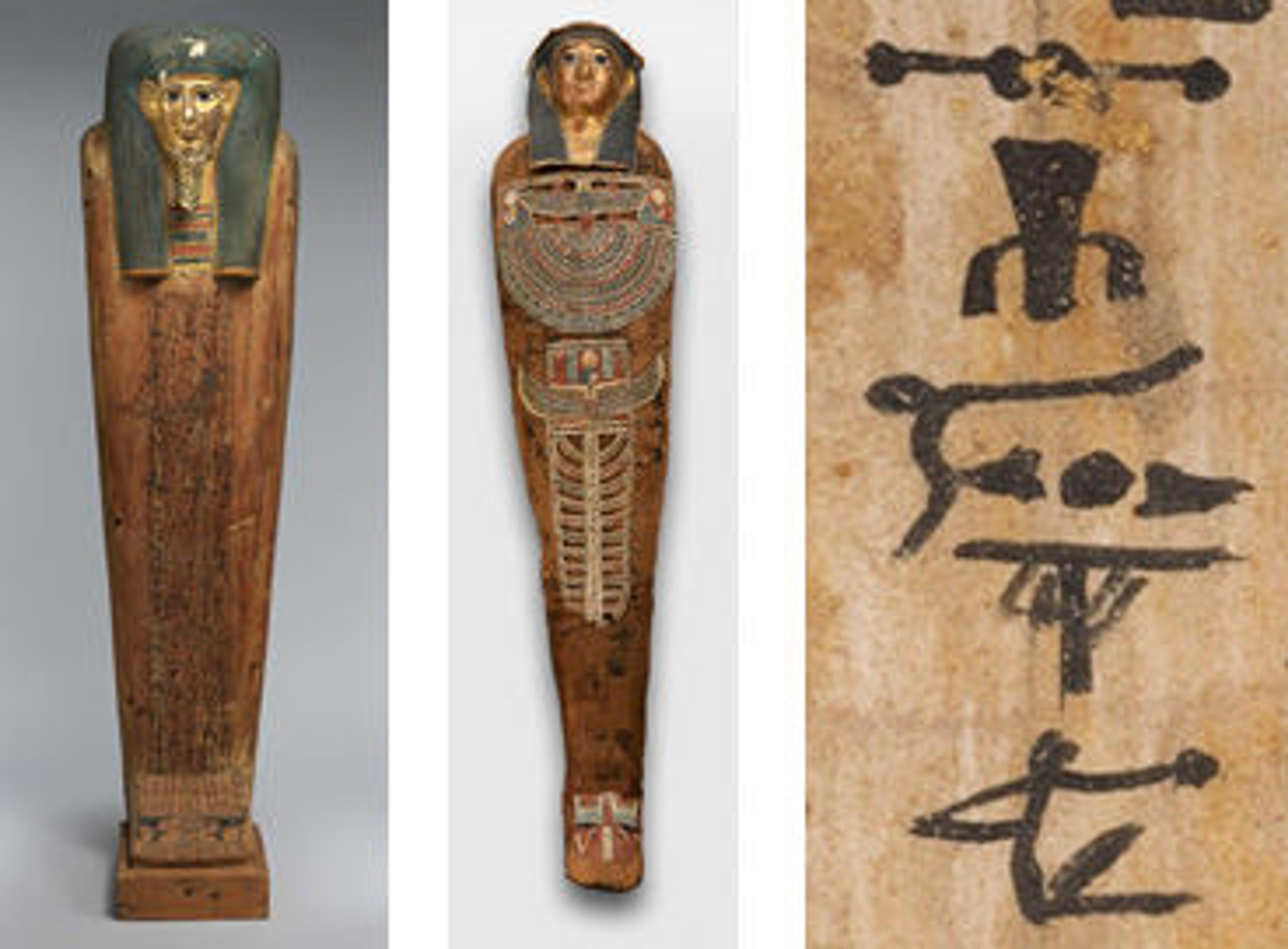

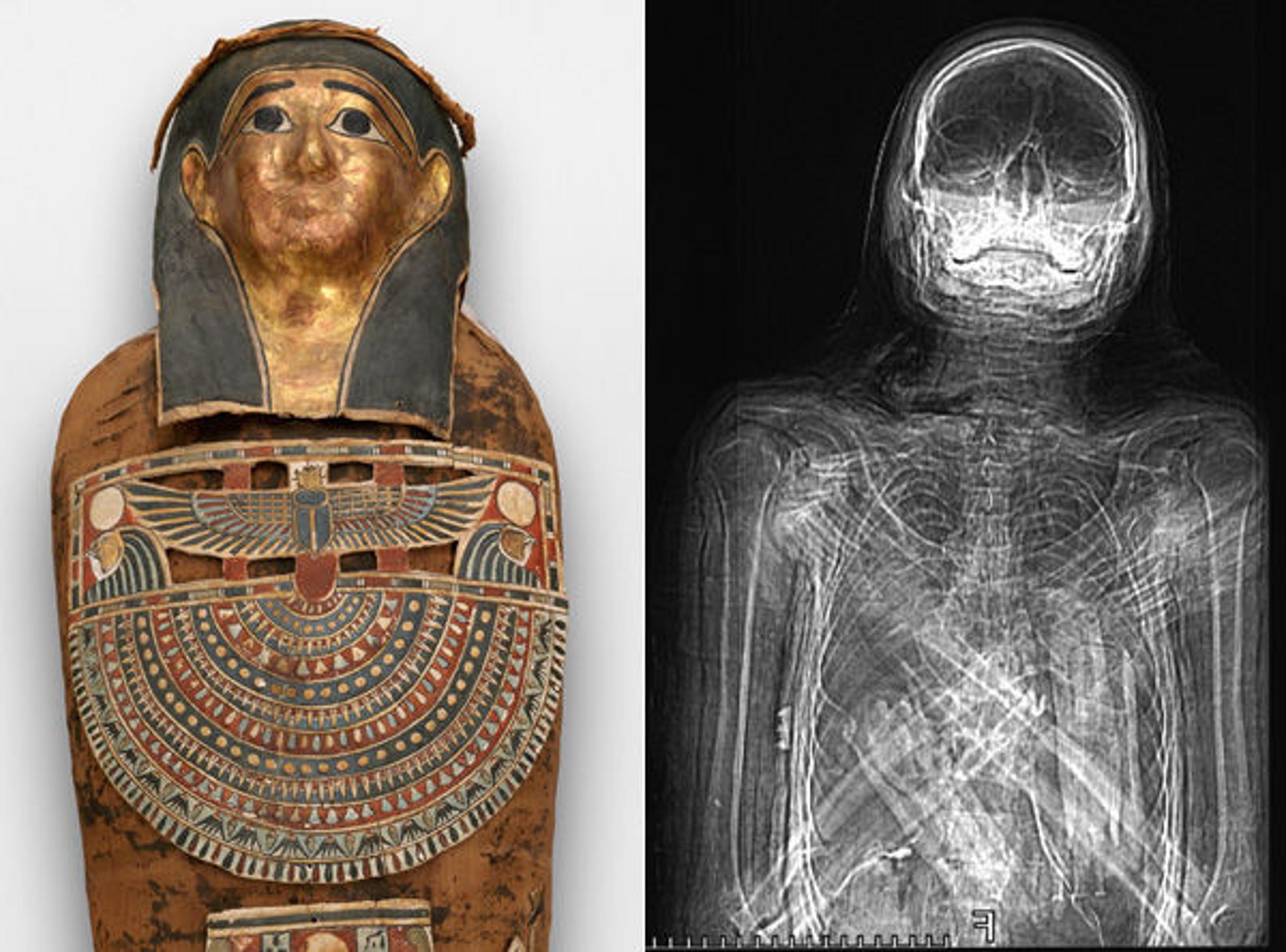

Fig. 1. Detail of the mummy of Nesmin with mummy mask. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Funds from various donors, 1886 (86.1.51).

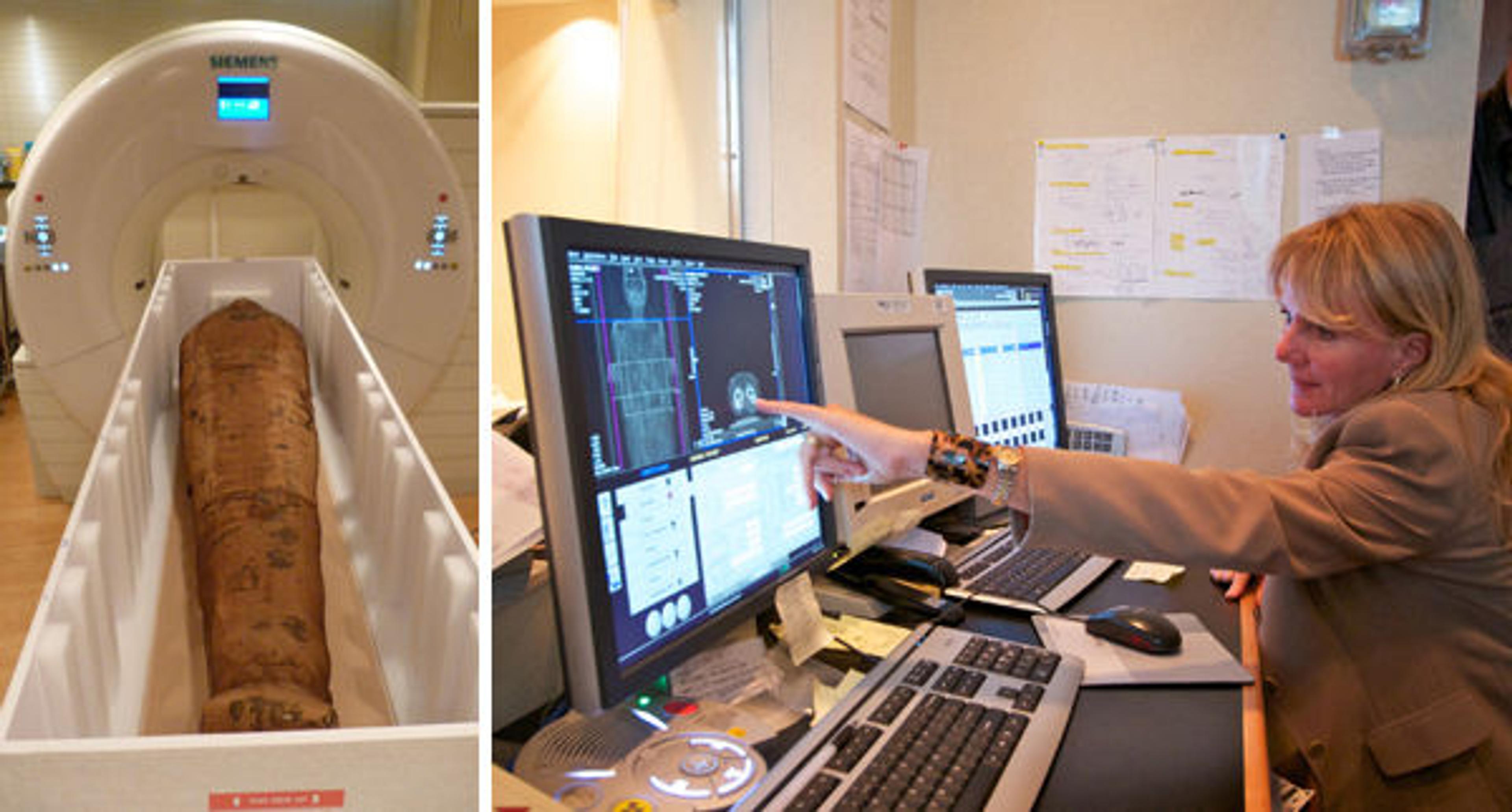

«For several years The Metropolitan Museum of Art has been collaborating with the NYU Langone Medical Center Department of Radiology, using computed tomography (CT) to study the Museum's collection.» In 2011 the mummy of Nesmin was scanned as part of this cooperation (figs. 5 and 6).1 The mummy was excavated at the site of Akhmim and, together with his coffin, bought by the Museum from the Egyptian government in 1886 (figs. 1–3). The mummy and coffin date to the Ptolemaic Period (332–30 B.C.); from the inscriptions on one of Nesmin's cartonnages and on his coffin we know his name and that he was a priest (fig. 4).

Fig. 2 (left). Coffin of Nesmin. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Funds from various donors, 1886 (86.1.50a,b). Fig. 3 (center). The mummy of Nesmin with mummy mask and other cartonnage elements. Fig. 4 (right). Detail of one of Nesmin's cartonnage elements with part of a hieroglyphic inscription that gives his name and his title, indicating that he was a priest.

Fig. 5 (left). The mummy of Nesmin in his transport box with padding material and braces removed, about to be scanned. Fig. 6 (right). Control booth of the CT scanner of the NYU Langone Medical Center. Dr. Georgeann McGuinness from the NYULMC Department of Radiology is noticing signs of arthritis in Nesmin's hips.

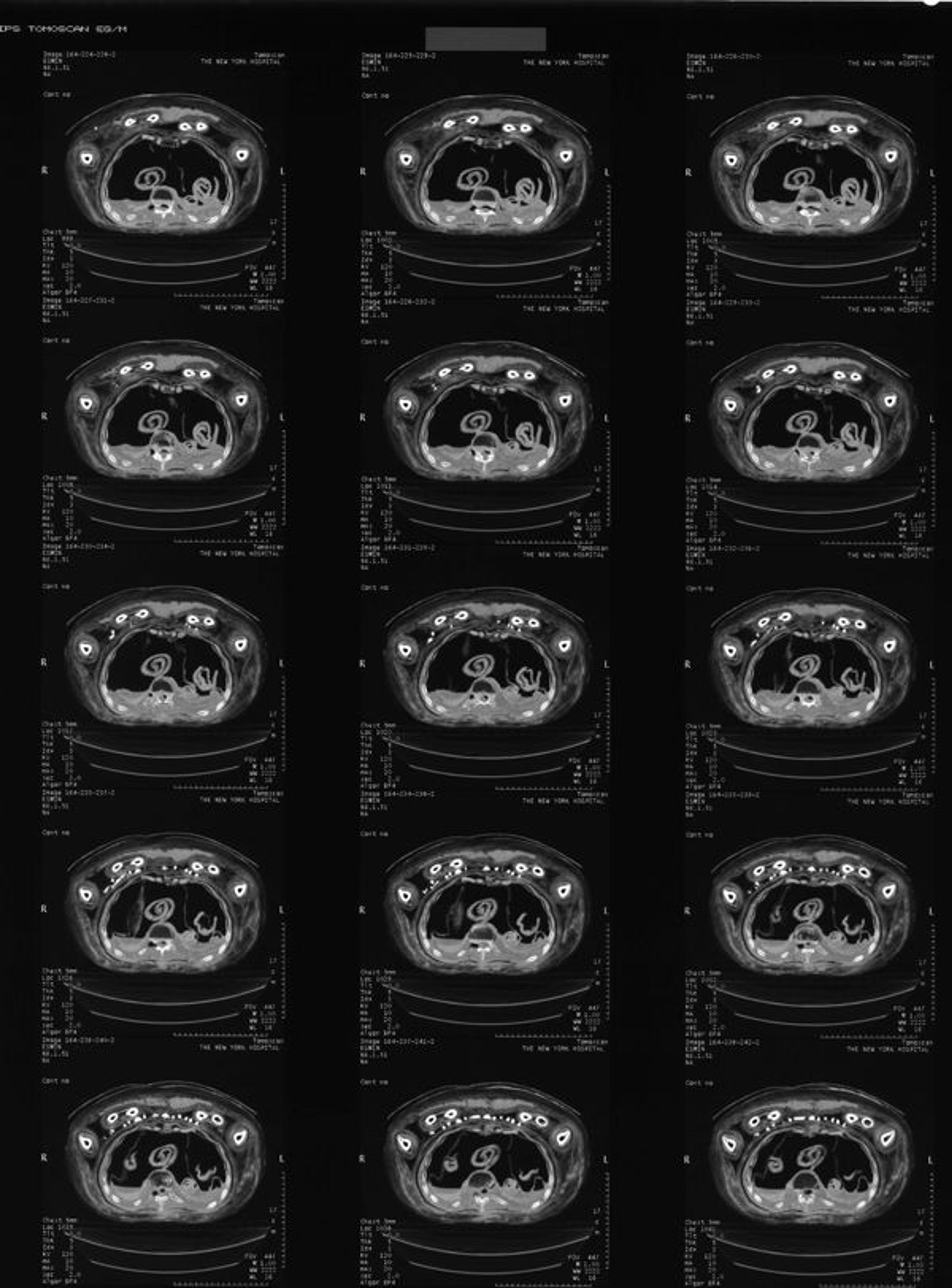

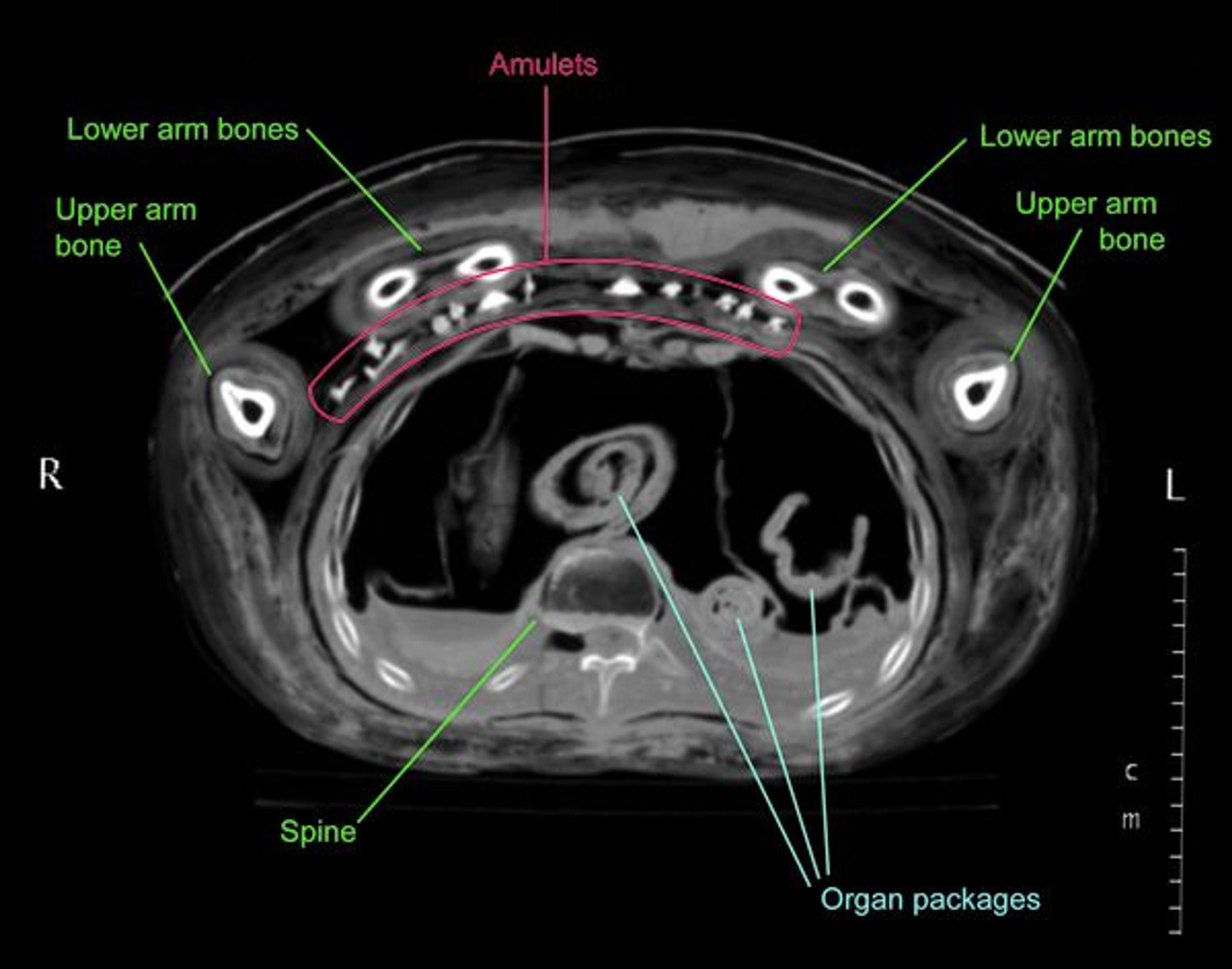

Older X-rays and CT scans of Nesmin that were taken in 1995 and 1997 (figs. 7–8, 10, and 13)2 had shown that his mummy is accompanied by a very large set of amulets (thirty-one in total) within the wrappings. The images that were produced at the time were on film and allowed the identification of the types of amulets (such as a standing god), but the information from these old images was limited and the visible details were not sufficient to permit the identification of the particular gods included, for example.

Fig. 7. Example of old film sheet with CT scan images from 1997.

Fig. 8. CT scan of the chest area from 1997 that shows a section of the chest with the amulets.

Fig. 9 (left). The mummy of Nesmin with mask and other cartonnage elements. Fig. 10 (right). Reconstruction of the CT scan data from 1997. Although it looks like an X-ray, the reconstruction is created from CT data.

Medical imaging technology and software have advanced so much over the last fifteen years that new reconstructions from the 2011 CT scan data show Nesmin's body and these small amulets (about 1–1 1/2 in.) with astonishing clarity (see figs. 11–12, and especially 14 and 16).

Fig. 11 (left). 2014 volumetric rendering of the mummy of Nesmin with the wrappings digitally removed to show his well-preserved body (more soft tissue is preserved on his arms and hands than is visible in this image) and the amulets that are placed within the wrappings. Fig. 12 (right). 2011 volumetric rendering of Nesmin's skeleton and his amulets, with the layers of wrappings and the soft tissue digitally removed. Note the crossed arms with the right hand open and the left one clenched; this is a common position in the Ptolemaic Period. The colors of all volumetric renderings are artificial.

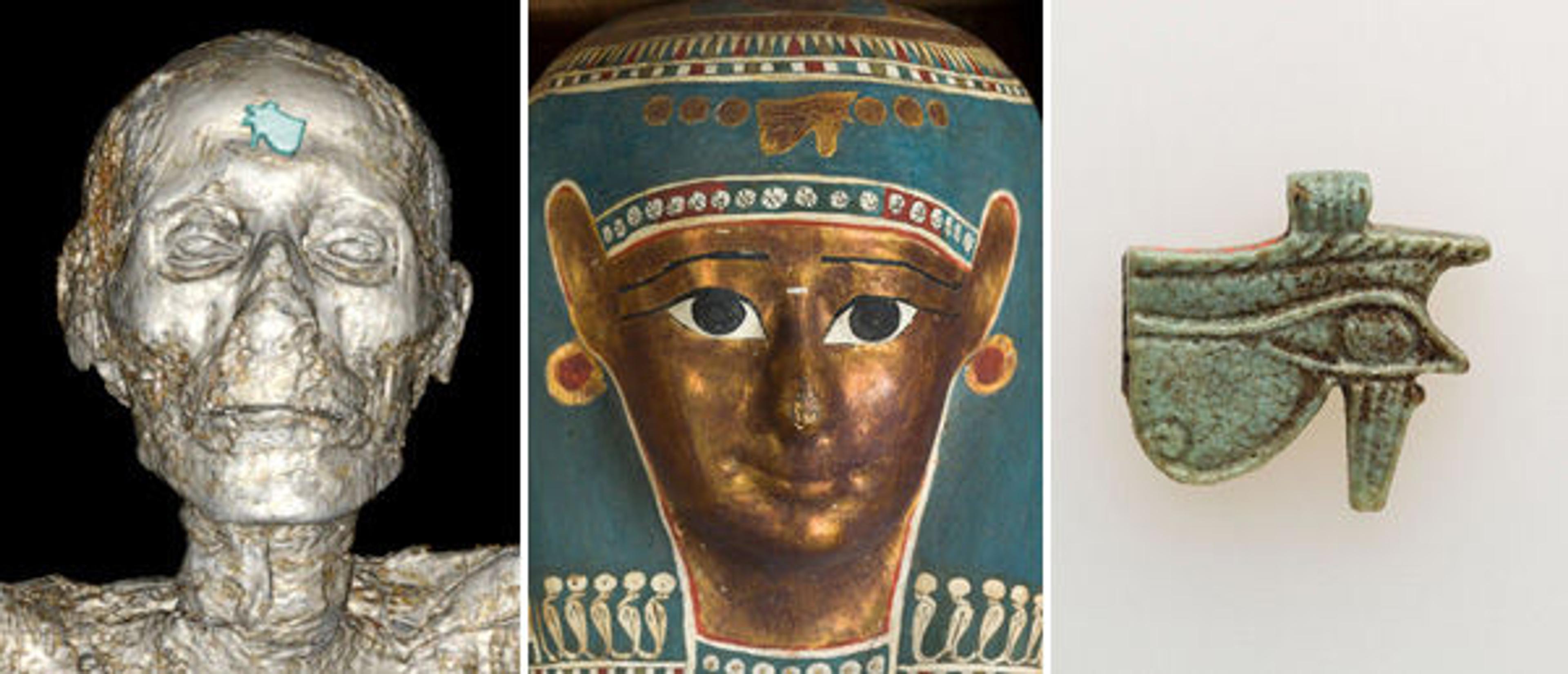

Fig. 13 (left). 1995 X-ray that faintly shows a triad amulet (about 1 1/2 in. high) within Nesmin's wrappings. Fig. 14 (center). 2011 volumetric rendering of the same triad amulet. Fig. 15 (right): Photograph of a similar triad amulet, Nephthys, Horus, and Isis. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917 (17.194.2246). Triad amulets usually depict the god Horus flanked by his mother Isis and his aunt Nephthys, as is the case here.

The NYULMC Department of Radiology produced some preliminary volumetric renderings in 2011 and a Museum intern worked last summer processing part of the 2011 CT data into additional visualizations, such as fig. 11, which allow us to see Nesmin's well-preserved soft tissue. Most fascinating are Nesmin's amulets, as his mummy is one of only a few in the world that is known to have such a large set of amulets still within its wrappings. One amulet of particular interest is visible on Nesmin's forehead (fig. 16). As a representation of the healed eye of the god Horus, this so-called wedjat eye was believed to have general healing and protective powers. Sometimes it is depicted on the forehead of mummy masks (fig. 17). Nesmin's amulet shows that such masks echoed an actual tradition of placing a real wedjat eye amulet on the dead person's forehead.

Fig. 16 (left). 2014 volumetric rendering of Nesmin's head with wedjat eye amulet on his forehead (highlighted in blue). Fig. 17 (center). Photograph of the mummy mask of Tasheriteniset with the depiction of a wedjat eye on the forehead. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1912 (12.182.48a). Fig. 18 (right). Photograph of a wedjat eye amulet from the Museum's collection (89.2.415, Gift of Joseph W. Drexel, 1889)

Radiographic analysis can not only detect objects within the wrappings, but it can also provide information about mummification techniques or the health of an individual. In Nesmin's case we can, for example, see that most of his organs were removed, mummified separately, and then placed back into the chest and stomach cavity (see fig. 8); this was a common practice in the Ptolemaic Period. Images of his hips revealed that he suffered from arthritis.3

Our research on the mummy of Nesmin is ongoing, and we are also currently working on new gallery labeling to present information about this mummy to our visitors.

[1] Special thanks are due to the NYU Langone Medical Center Department of Radiology, in particular to Georgeann McGuinness, MD, and Emilio Vega BS, RT, who performed the CT scans and produced preliminary volumetric renderings. We are also grateful to Daniel Mindich, whose donation supported the transport of the mummy. Many staff members of the Museum participated in arranging and preparing the packing and transport. We would like to thank Sarah Boyd, Emilia Cortes, Elizabeth Fiorentino, Ann Heywood, Dennis Kelly, Gerald Lunney, Isidoro Salerno, and Crayton Sohan and his team. We are also very grateful to Paco Link from the Museum's Digital Media Department, who has been working with the Department of Egyptian Art on this project and whose help has been invaluable.

[2] The 1997 radiographic project analyzed several mummies and was undertaken on the Museum's premises by the Department of Egyptian Art together with the physician David Mininberg and the Department of Object Conservation. Generous support was provided at the time from Philips Medical Systems, General Electric, Eastman Kodak, and the New York Hospital Department of Radiology of the Weill Cornell Medical College. Preliminary X-rays were taken in the Department of Object Conservation in 1995 by Ann Heywood and Deborah Schorsch.

[3] Arthritis of his hips was first noted in 2011 by Georgeann McGuinness, MD, from the NYU Langone Medical Center Department of Radiology.