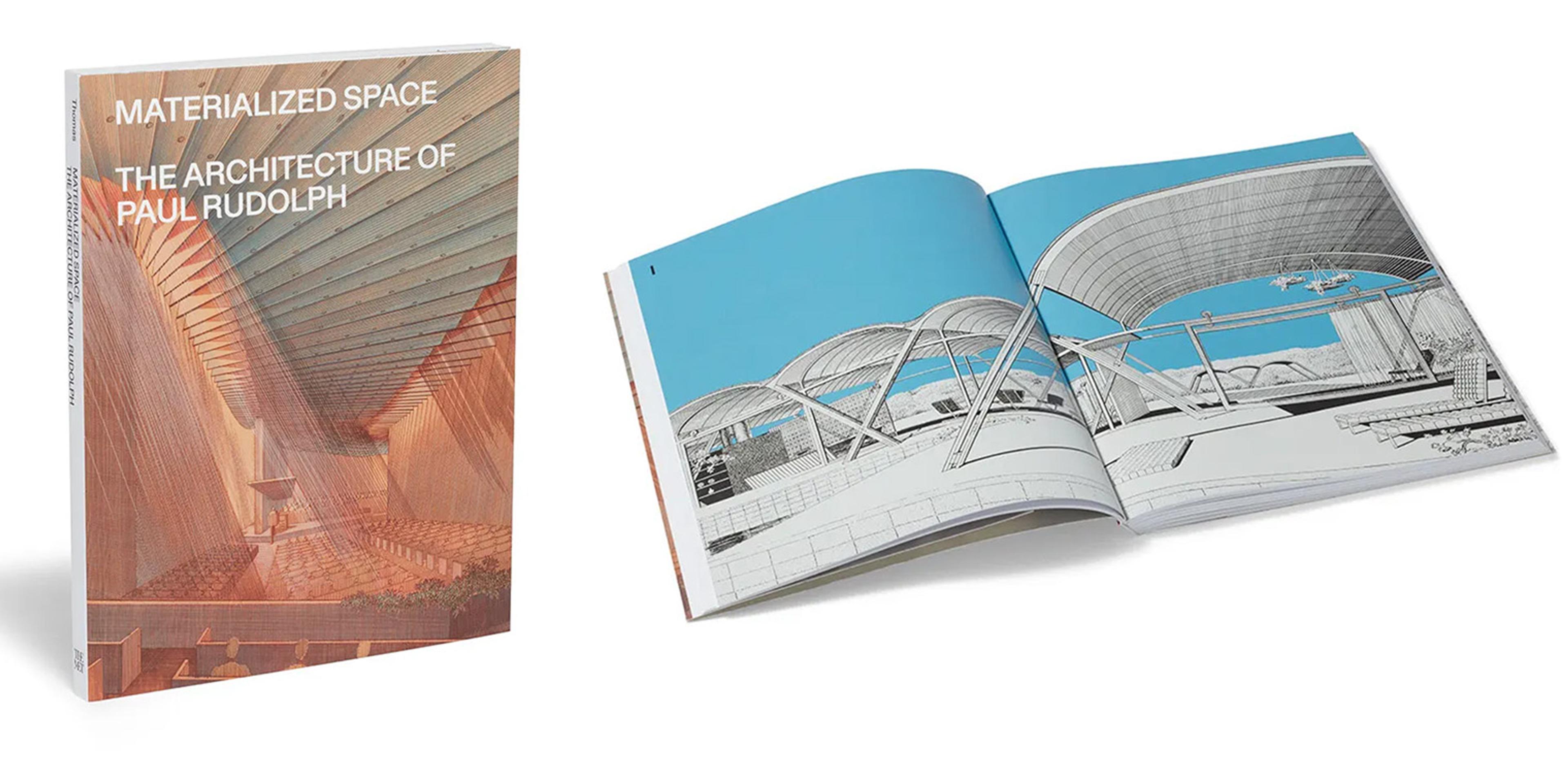

The exhibition catalogue Materialized Space: The Architecture of Paul Rudolph explores the influential work of twentieth-century architect Paul Rudolph, celebrated for his iconic modern homes and striking Brutalist structures. This publication features seventy-five illustrations, including images of Rudolph’s buildings, drawings, models, furniture, and press clippings, providing a comprehensive look at his significant contributions to architecture. It traces his journey from early experimental houses in Florida in the 1940s to the interiors of New York townhouses in the 1970s as well as his mixed-use skyscraper projects in Asia during the 1980s.

In my conversation with Abraham Thomas, curator of the exhibition and author of the publication, we discuss the need to reassess Paul Rudolph’s legacy and how Materialized Space marks an important first step in this reevaluation.

Materialized Space: The Architecture of Paul Rudolph is available at The Met Store and Met Publications

Lina Palazzo:

This book is unique in that it covers all stages of Paul Rudolph's career, from the Sarasota modernist residencies through his peak at Yale to his string of floundering commissions in the 1970s and finally his renaissance in Hong Kong, Singapore, and Jakarta. How did these eras influence each other, and what is the importance of seeing this complete trajectory?

Abraham Thomas:

The chapters of Rudolph’s career build off one another. For example, you can see the origin of his megastructures in his very early Florida houses; he was always thinking about modularity, modern materials, and the urgent need to build public housing more efficiently and at a greater scale in a cost-efficient way. He was always interested in building at a city scale, as evinced by his idea of the civic campus in his buildings for Yale University during his tenure as head of the architecture school. That period of Brutalism and his use of concrete derives from his long-held interest in city-making and constructing at scale. When he finally left Yale and academia in the 1960s, he did so because he wanted to become a skyscraper architect, and he relocated permanently to New York.

He was always thinking about modularity, modern materials, and the urgent need to build public housing more efficiently and at a greater scale in a cost-efficient way.

But he never really got to do that type of building in the States. In the 1970s he struggled to find architectural commissions at an architectural scale, which moved him toward designing interiors. Near the end of his career, when working on commissions in Asia, he finally had an opportunity to work with well-resourced clients at a scale that gave him a little more freedom. The mixed-use office towers, residential towers, and commercial retail spaces allowed him to implement the ideas about urbanism, place, and city-making that he'd been thinking about since the 1950s.

While it may be hard to recognize a Rudolph building because each era of his career is so different, there are interesting through-lines across his work. For this reason, the book and exhibition are not strictly chronological but arranged thematically to highlight these connections.

Palazzo:

Your introduction begins by quoting Rudolph’s obituary in the New York Times, which sums up his career as “a perplexing legacy that will take many years to untangle,” and you go on to discuss how historians have grappled with this controversial figure whose career has often been dismissed as an inconvenient blip within a grand arc of late modernism. How do you hope to change this perception of Rudolph through this publication?

Thomas:

I want to celebrate the messiness that some might see within Rudolph’s work. He doesn't adhere to orthodoxies as in the careers of his peers, such as Louis Kahn or Eero Saarinen. One major objective of this book is to shine a light on an underrecognized architect working on diverse projects at various magnitudes who didn’t fit a neat categorization within modernism. Rudolph once described his work as ranging “from Christmas lights to megastructures.” From his experiments with space, lighting, and design to massive urban projects like the Lower Manhattan Expressway, I've always been intrigued by Rudolph because his career spanned such a range of contexts. My hope is for the book to showcase his unique story.

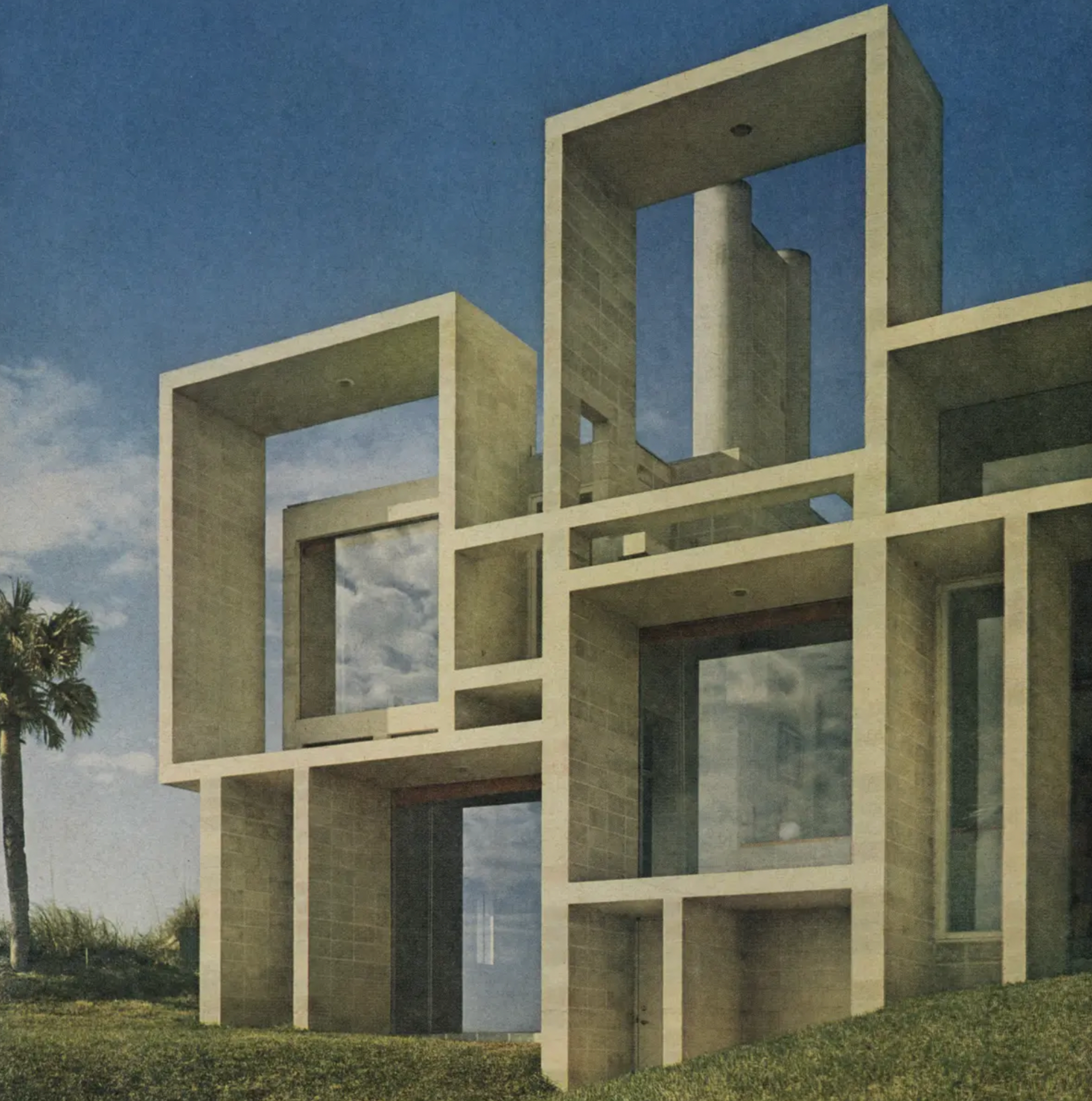

Walker Guest House, Sanibel Island, Florida, 1952. Photography by Ezra Stroller for House Beautiful. Paul Rudolph Collection, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division. © Ezra Stroller/ Esto, Yossi Milo Gallery

Palazzo:

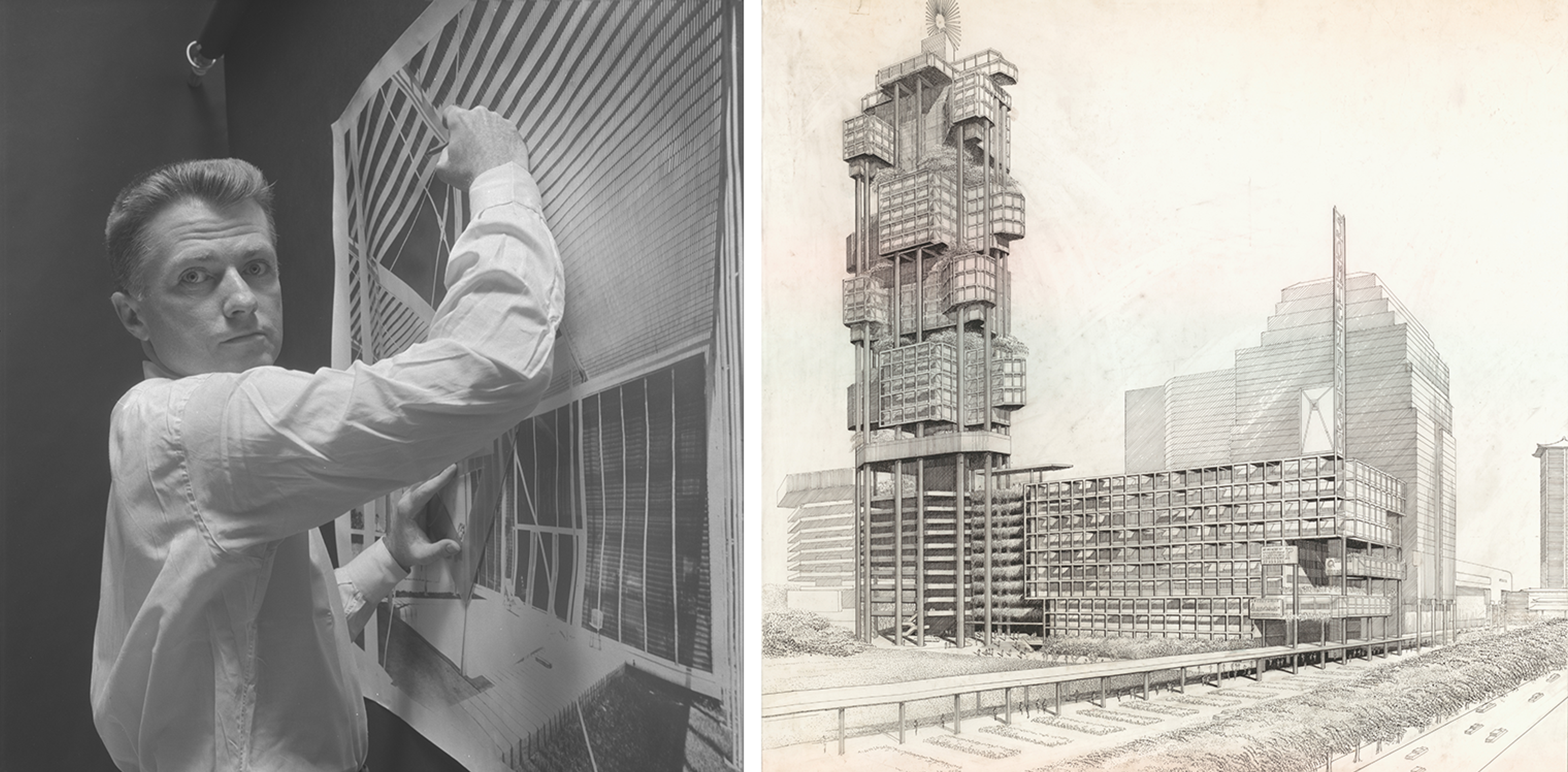

One prominent aspect of Rudolph’s work is draftsmanship. This book features drawings by Rudolph, some of which are published for the first time. Can you speak more about Rudolph as a draftsman, and can you walk me through how studying his drawings has changed your experience of his work?

Thomas:

One of the reasons I have been drawn to Rudolph is his talent as a draftsman. I was always enamored by his drawings. Many of these drawings—all from the Library of Congress Archive—have never been shown before, so it is exciting to present them to a larger audience.

It is rare for a lead architect to complete presentation renderings themselves, but Rudolph did. He loved the practice of drawing, and in fact, he talks about it influencing his choice of material; his interest in concrete seems to rise from his skill and enjoyment in rendering its texture in pencil and pen and ink when compared with brickwork, glass, or steel.

In both the book and the exhibition, I've foregrounded materials such as drawings, drawing tools, magazines, and ephemera. These objects give a sense of the life of the studio and the working process of an architect. For some projects that were never built, have been demolished, or have been altered dramatically, these drawings are the only surviving traces. They not only convey Rudolph’s vision but are used in architectural school didactics. Rudolph’s approach to drawing emphasizes the medium more generally as a tool for designing, communicating, testing, and sharing ideas.

Left: Rudolph working on drawing copy for the Hiss House (Umbrella House) in 1955. Photograph by Hans Namuth. Paul Rudolph Collection, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division. © 1991 Hans Namuth Estate, Courtesy Center for Creative Photography Right: Perspective drawing of the International Building for Hong Fok Corporation (unbuilt), Singapore, 1990. Ink on tracing paper, 31 ⅞ X 33 ¼ in. (81 X 85.6 cm) Paul Rudolph Collection, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, (LC-DIG-ppmsca-12345)

Palazzo:

On the topic of foregrounding materials, can you discuss the meaning of “materialized space” in Rudolph’s buildings and drawings? Why did you choose this phrase as the title of this book and exhibition?

Thomas:

Rudolph often gave lectures on the theme of space. Even though people associate him with Brutalism and its use of concrete, which some critics deemed overpowering and sometimes not appropriate for context and use, Rudolph was much more interested in how these materials helped define and shape space within his buildings. He explored transitions between different areas of the building and manipulated light to create a sense of space.

Materials, to Rudolph, were such an important tool for thinking about architectural history, place, and urbanism. His interest in materiality, ornamentation, decoration, and texture is something I wanted to highlight in the title. Materialized Space brought two related aspects of Rudolph’s work into focus: he added a sense of materiality to the space, but also, with materials, helped to define space as one volume with contrasts of shadow and light.

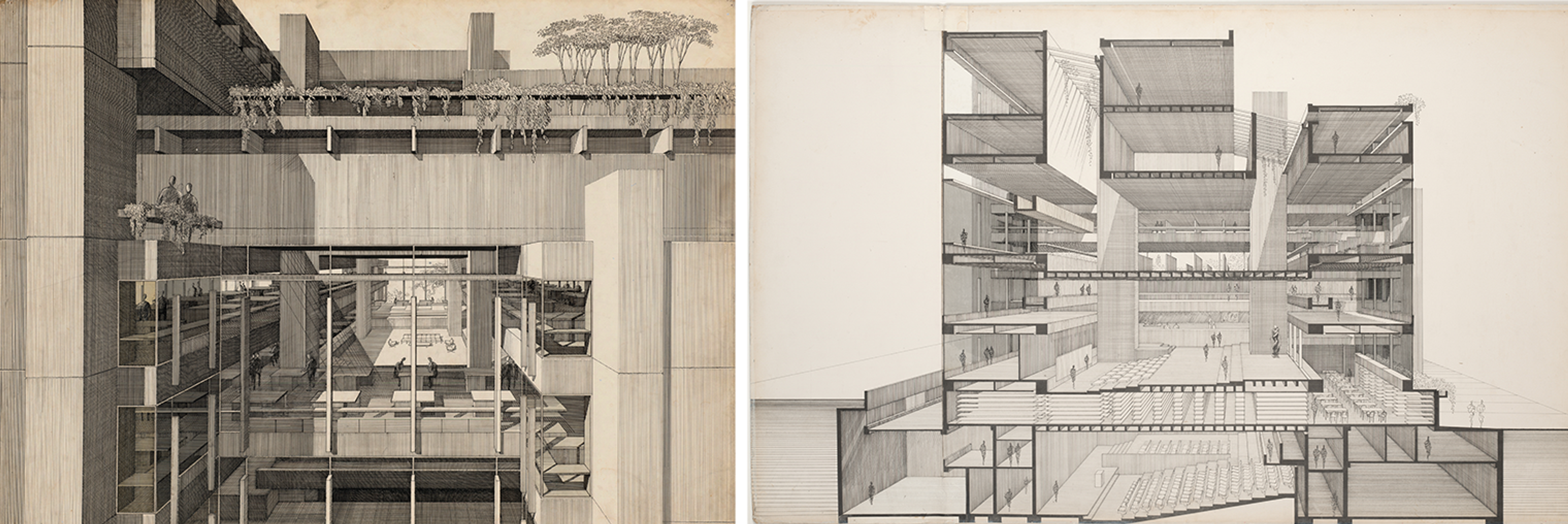

The Yale Art and Architecture Building, today called Rudolph Hall, is considered by many to be his definitive building. It's a large focus in the book and a great example of this idea of “materialized space.” In this seven-story building, Rudolph manages to create thirty-six different levels, which demonstrates how Rudolph controls and conveys the energy of architectural space.

Left: Perspective drawing of the Art and Architecture Building, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, 1958. Ink on board, 30 X 40 in. (76.2 X 101.6 cm).The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Gift of the architect (405.1985). Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY Right: Perspective section drawing of the Art and Architecture Building, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, 1958. Pen and ink, graphite, and plastic film with halftone pattern, on illustration board, 36 ⅞ X 53 ⅝ X 2 in. ( 93.6 X 136.2 X 5.1 cm). School of Architecture, Yale University, Memorabilia (RU 925). Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library

The drawing for the Yale Art and Architecture building is a particular type of architectural drawing called perspectival section or sectional perspective, which became Rudolph’s signature style. While he didn’t invent it, he really pioneered this drawing technique that combines a perspective drawing and a section drawing. It allows the viewer to see inside the building with its relationships between the floors, almost like a doll’s house that’s sliced open; it’s a great example of how Rudolph thought about space, which is closely related to the idea of materiality—in this case, concrete—but also more generally, texture.

Palazzo:

Besides concrete, can you speak more about the innovative materials and modular construction methods Paul Rudolph used?

Thomas:

Throughout his career, Rudolph showed a particular interest in industrial materials as well as newer modern materials. You can see this interest manifested from his very early Florida houses through to the extraordinary materials that he was using to outfit his New York apartment. From the 1960s through to the ’90s, he was constantly creating experimental environments in his home at 23 Beekman Place.

The exterior of 23 Beekman Place, showing the penthouse quadruplex. © Peter Aaron/OTTO

I argue that this interest in materials stems from his background working on repairing ships for the U.S. Navy in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, which exposed him to plastic, plywood, aluminum, and other materials that were being deployed during the Second World War for rapid construction.

In the 1960s and ’70s, Rudolph used materials like foam, Lucite, and Perspex. These plastics and reflective materials helped Rudolph think about space differently. He used Chrome-plated steel in a high-tech approach to architectural materials. He also thought a lot about modularity, and the idea of creating pieces that could be adapted for different needs. For example, in the book and exhibition we feature chairs that he fashioned using a Danish off-the-shelf modular shelving system and ball caster wheels commonly found on hospital gurneys.

Rolling Lucite and tubular steel dining table and chairs designed by Rudolph for his Beekman Place apartment. Photograph by Peter Aaron. LC-DIG-ppmsca-89926, Library of Congress © Peter Aaron/OTTO

Palazzo:

As you’re describing, the whole rhetoric of his work was utilizing innovative materials and modular construction methods to unify space, interior and exterior, and in doing so, unifying communities. However, as you discuss in the book, Rudolph’s critics ironically find fault with the lack of unity in his ideas.

Thomas:

Exactly. Even though it might look like Rudolph is working with many separate ideas, they all interconnect. His experience at the Brooklyn Navy Yard developed his interest in factory-like assembly, prefabrication, and standardized components and parts; he took inspiration from how building at mass scale was achieved. He began imagining how using factory-like assembly, and standardized components and modules that, as I mention in the book and exhibition, can be “plugged in and plugged out” could allow him to construct buildings that were extendable to a theoretically infinite scale, but at the same time, quickly adjusted depending on context and purpose. He employed this “plugging in and plugging out” from projects ranging from the Oriental Masonic Gardens in New Haven to the Fort Lincoln project for Washington, DC as well as the Lower Manhattan Expressway.

For the Oriental Masonic Gardens, Rudolph, taking what he saw at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, used the idea of adapting self-contained mobile home units—which he termed the “20th century brick"—to build cities like Lego constructions. He believed that if he built large towers with these modules of self-contained units like Lego, he could build these cities. Hence, for Rudolph, using self-contained mobile units allowed him to play around with the idea of city and architecture becoming one. Using industrial prefabrication to create new systems of construction and assembly that were cost-efficient than conventional means thus not only unlocked potential for building at larger scales, but also created modules that were fitted to the programmatic needs of buildings or complexes of buildings. While his projects could be seen as vastly different in nature, they were all woven together by this thread of knowledge and inspiration taken from what he saw at the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

Palazzo:

Rudolph's legacy goes far beyond his own plans and structures. Can you speak about his role as a professor at Yale, his influence on the next generation of architects, and ultimately, how his legacy is still felt to this day?

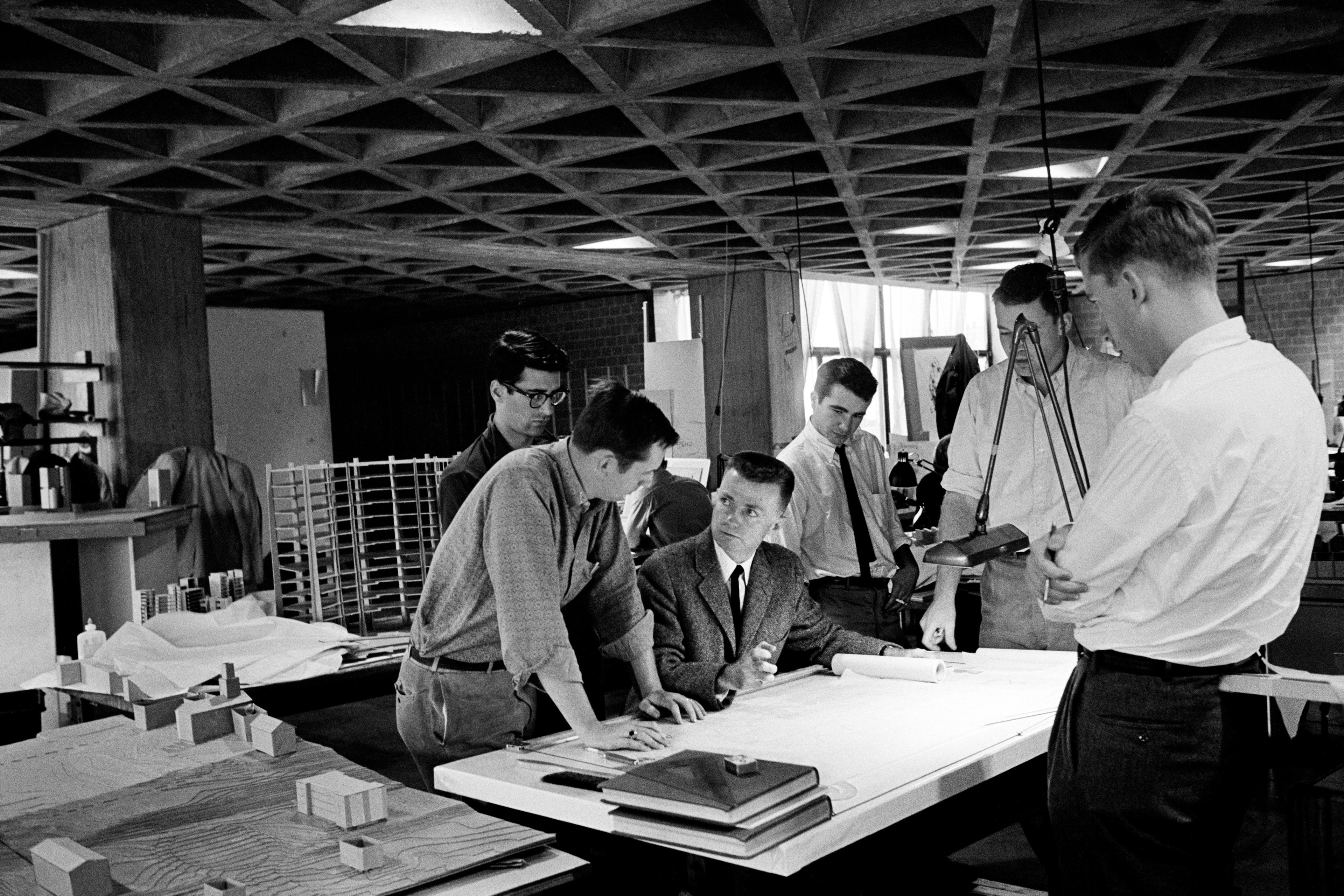

Rudolph with his architectural students at Yale, before the opening of the Art and Architecture Building, ca. 1962. Photograph by Elliott Rewet, for Vogue. Paul Rudolph Collection, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division. © Elliot Erwin/ Magnum Photos

Thomas:

Rudolph was astonishingly young when he became chairman at Yale—he was not even forty when appointed. Rudolph’s teaching style was described as brutal, and, to some, he was both the most harsh and most amazing teacher of their education. So many of today’s well-known architects studied under him and cite how influential he was as a teacher. For example, Norman Foster stated that Rudolph was the main reason he chose to study architecture at Yale. Studying alongside Foster was Richard Rogers, and other students of Rudolph's at Yale from this generation included Stanley Tigerman and Robert A.M. Stern—not to mention visiting critics as varied as James Stirling and Serge Chermayeff.

The styles of Rudolph’s acolytes are all so different. This is reflective not only of Rudolph’s own diversity of work but also of the faculty he developed at Yale. He wanted to create a very broad platform that didn't necessarily reflect his own design approaches. Rudolph brought on and did not shy away from people who disagreed with him regarding architectural ideas. He liked that mix.

Advertisement for Martin Marietta concrete company, “A city to grow up in,” featuring an architectural model of the Buffalo Waterfront redevelopment project (partially demolished), Buffalo, New York, ca. 1970. Paul Rudolph Collection, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division,(LC-DIG-ppmsca-12345)

It’s fascinating to see how that legacy continued not just through these architects but also in the way we think about architecture today. The urgent need for public housing, how to create mixed-use public space, modular construction, and rapid deployment of architecture are things that we still talk about today—in short, the role of architecture in a community. These are all things that Rudolph was trying to get right.

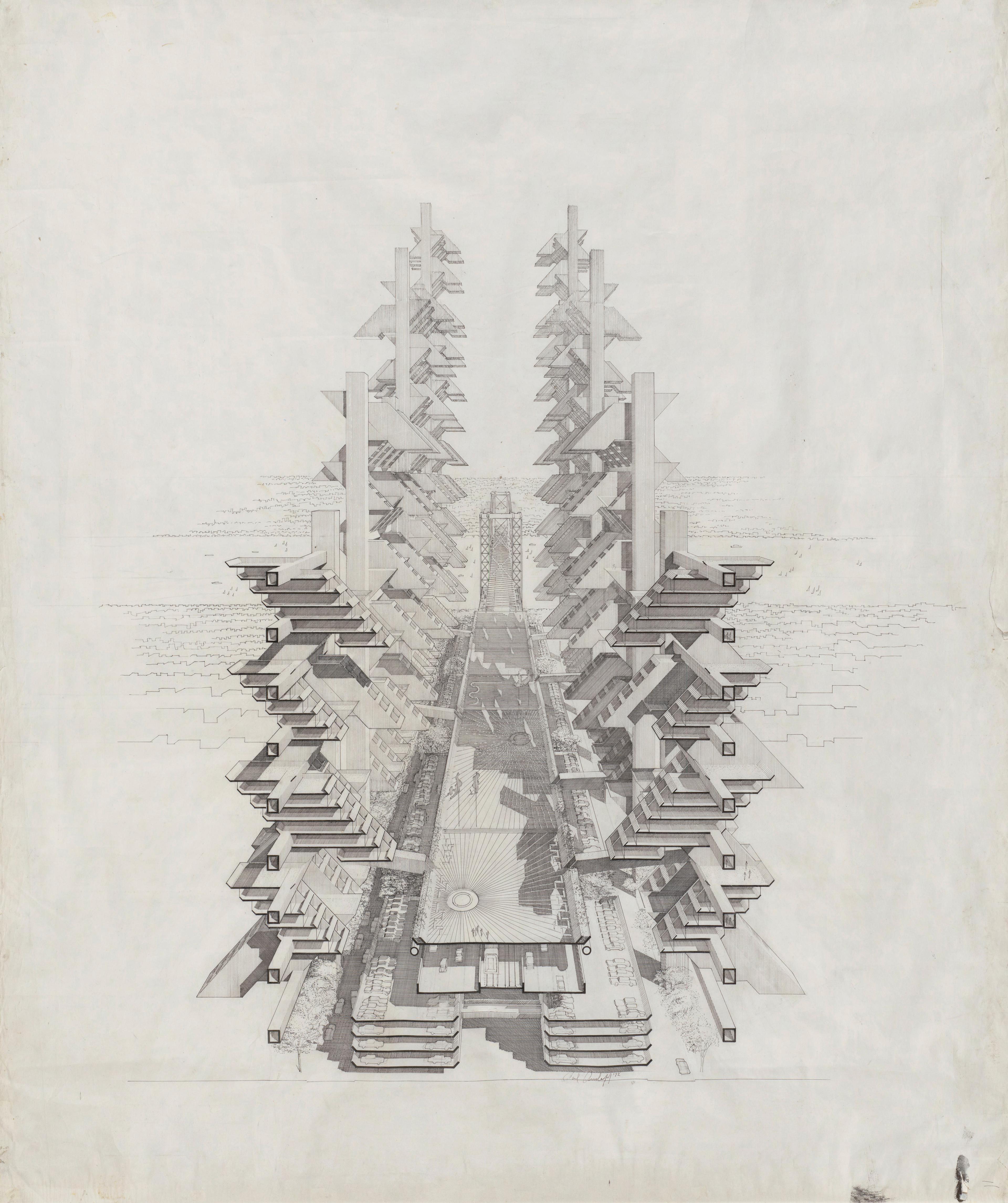

His controversial project—and perhaps best known—the Lower Manhattan Expressway is in itself such an interesting concept as a modularly constructed megastructure with an almost science-fiction level of building at the city scale. It was terrifying to many. But when considering this unrealized project, it is important to remember that Rudolph was creating something in response to Robert Moses’s much more extreme proposal of driving a massive highway through the city without considering its impact on infrastructure. Rudolph’s plan tried to stitch together the community infrastructure—everything from public transportation to public pedestrian walkways, housing, retail spaces, and plazas, all around this idea of the highway. Though not realized, the project still has a robust legacy as it dealt with ideas of building in a city with consideration of urban density and multiple mixed-use integrated functions, which is still a major concern of architects and city planners today.

Perspective section drawing of the Lower Manhattan Expressway / City Corridor project (unbuilt), New York, 40 X 33 ½ in. (101.6 X 85.1 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Gift of the Howard Gilman Foundation (1290.2000). Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

Such a large part of understanding Rudolph’s legacy is to live in or use one of his buildings, and I’m trying to simulate that as much as possible in the show and catalogue. One way we have done so is by featuring the work of architectural photographer Ezra Stoller. He is synonymous with this generation of architects, and he had a very close relationship with Rudolph. Stoller’s work shows what it's like to experience a Rudolph space in a different way than the drawing or models.

Palazzo:

Considering Rudolph’s legacy more broadly, could you discuss The Halston House and Rudolph’s influence on popular culture?

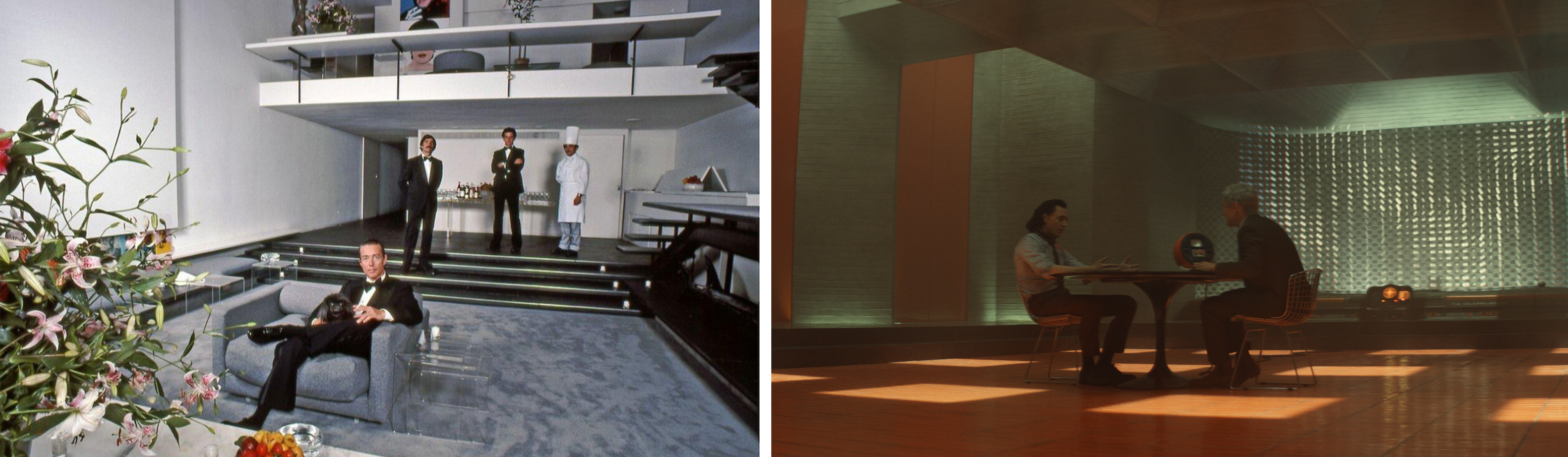

Left: Hirsch (Halston) Residence, 101 East 63rd St., New York City. Photo of Halston taken in 1978. © Harry Benson Right: Production still from Marvel Studios’ Loki, season 1, episode 4, 2021. Courtesy of Marvel Studios

Thomas:

Yes, that house became the site of legendary after-parties for Studio 54 and the so-called Halston Happenings. Andy Warhol took several candid photographs of Bianca Jagger, Liza Minnelli, and others attending those parties. I'm always interested in the broader application of architecture and how it permeates through popular culture. I explore this in the book by looking at echoes of Rudolph’s style in contemporary cinema. For example, the set design from Marvel’s Loki (2021) shows how production designers have been inspired by Rudolph’s architecture.

Rudolph’s career touches upon so many key architectural and pop culture moments during the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. He has never had a major exhibition before now, and I am so excited to share his work with our audiences.