Since 1985, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) has commissioned more than four hundred permanent public artworks. Flight into Egypt: Black Artists and Ancient Egypt, 1876–Now is the first exhibition at The Met to designate site-specific art installations within the transit system as part of a show. Three works were selected, and their significance is explored further here.

Houston Conwill (American, 1947–2016). Detail of The Open Secret, commissioned 1984, unveiled 1986. Bronze relief, located at New York City Transit 125th Street station (4, 5, 6). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. © Houston Conwill. Photo: Trent Reeves

Four distinct emblems of black life exist at the juncture of Lexington Avenue and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard (125th Street) in Harlem. Beneath the fluorescent lights of the underground station and embedded in walls of gridded white tile, these polychrome bronze reliefs by American multidisciplinary artist Houston Conwill represent the first commission by the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) to be installed in the subway. Collectively titled The Open Secret (1984/86), they serve as monuments to the Harlem community of the 1980s. Located within a two-mile radius of this project, Maren Hassinger’s Message from Malcolm (1998) and Terry Adkins’s Harlem Encore (1999)—in which Harlem is similarly both site and subject—were unveiled the following decade. While disparate in style and form, these three site-specific works all visualize claims to ancient Egypt, symbolizing continued kinship with this ancient African culture and signaling its resonance within the global diaspora. In the 1920s and 1930s, ancient Egypt functioned as a powerful metaphor of ancestral achievement and belonging for the Black artists and writers associated with the Harlem Renaissance, a period of creative and cultural innovation centered in Harlem. Conwill, Hassinger, and Adkins extend this tradition with projects that vibrate with the symbolic resonance of ancient Egypt at their core, while celebrating histories and memories intrinsic to New York.

During the post–World War II era, as attention shifted to automobile infrastructure, New York’s subway system began to be perceived as unfashionable and outdated.[1] The city teetered on the brink of bankruptcy and subway construction halted. By the early 1980s, however, New York City began recovering from its fiscal downturn and established comprehensive plans to repair and maintain all MTA transit properties, from subways to commuter railroads—with art as a strategic component of this regeneration.[2] In 1982, the city passed the Percent for Art law, which required that one percent of construction costs for certain public buildings, such as libraries, schools, and courthouses, be allocated to the installation of art. Conwill’s The Open Secret—initially commissioned in 1984 by an arts panel formed in association with Percent for Art and chaired by Henry Geldzahler, the founding curator of contemporary art at The Met—was eventually absorbed into the MTA’s newly established Arts for Transit Program, now known as Arts & Design.[3] Created amid revitalization efforts above and below ground, The Open Secret symbolizes the historic preservation and public art movements that emerged in the wake of the prolonged urban decline of the 1960s and 1970s.

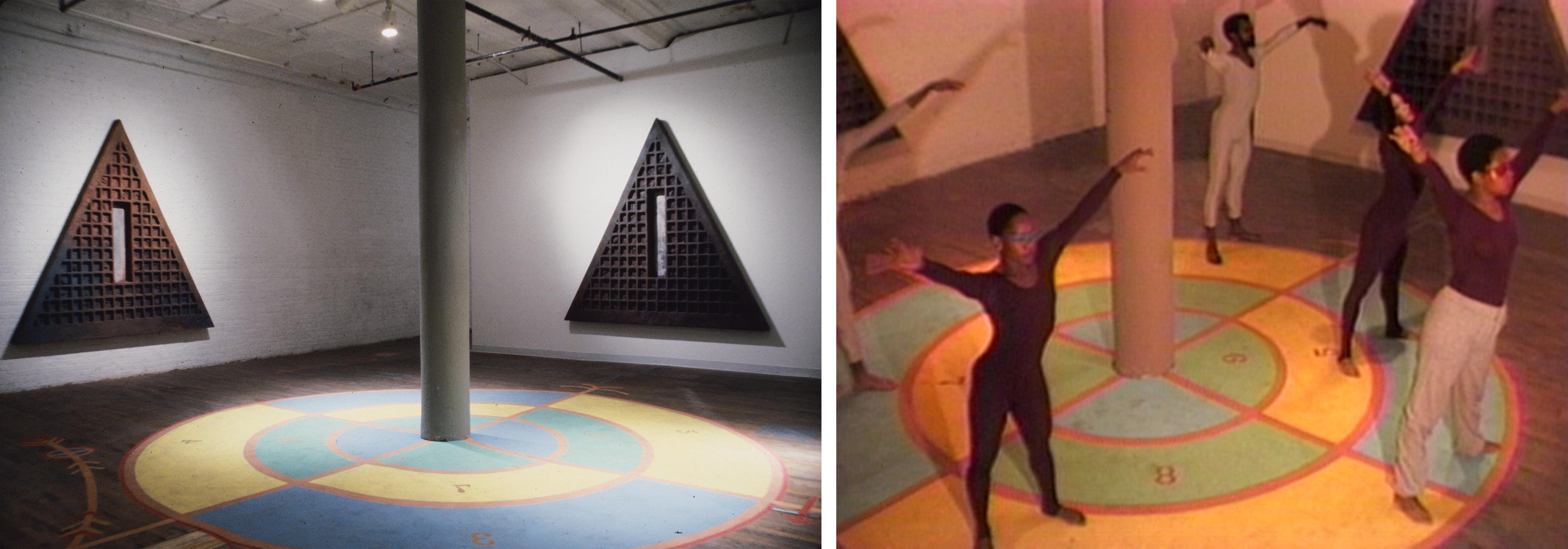

Left: Houston Conwill (American, 1947–2016). Cakewalk, 1983. Acrylic on linoleum floor with four wall reliefs of earth, wood, mirror, and pigment, originally installed at Just Above Midtown/Downtown, New York. Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY. Right: Ulysses Jenkins (American, born 1946). Still from Cake Walk, 1983. Video, color, sound, 26 min., 28 sec. Image courtesy of Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI), New York

Comprising two sets of graphically dense triangles on opposing walls, The Open Secret explores ancient Egyptian architecture, movement-based activation, and community engagement, themes the artist and former Benedictine monk had explored since the mid-1970s. For instance, Cakewalk (1983), an installation whose layout is echoed in The Open Secret, takes as its subject the cakewalk dance, a shuffling movement originally performed by enslaved people as an act of parody and resistance against white supremacy.[4] Within Linda Goode Bryant's Just Above Midtown (JAM) gallery, the artist broke apart the pyramidal form of his earlier sculpture Seven Storey Mountain (1982), placing each of its four sides on a separate wall and freeing the floor for choreographed performance, as seen in a 1983 film by the video artist Ulysses Jenkins. This open space, an integral component of the installation, allowed for moments of collective movement with the inherent resiliency of the dance as its premise. Building on this notion, The Open Secret—including the walkway that its bronze triangles frame—fosters a ceremonial environment for reflecting on the past while performing quotidian actions in the present. Conwill described his subway commission as an attempt “to capture the present for future generations of people through a ritual process: the creation of sacred spaces and the involvement of a community of people in bearing witness to the process and making it complete.”[5]

Conwill’s exploration of history and memory in The Open Secret is exemplified by the recessed time capsules ensconced within two of its triangles. As the artist explained, these “[hold] information and ‘secrets’ about a certain place at a certain time—Harlem in the 1980s.”[6] Here, he draws a connection to his earlier work Joyful Mysteries (1984), composed of seven bronze time capsules that contain the confidential testaments of seven distinguished Black Americans, from writer Toni Morrison to opera singer Leontyne Price. While these have been buried in the Studio Museum in Harlem’s sculpture garden, The Open Secret’s time capsules remain visually accessible, set within triangular reliefs that echo the funerary purpose of the ancient Egyptian pyramids. While their contents remain intentionally opaque, the dense array of iconography on their surfaces—derived from Dogon, Yoruba, Kongolese, and Kemetic imagery—speaks to Harlem’s Black community, present and future.

Maren Hassinger (American, born 1947). Detail of Message from Malcolm, 1998. Mosaic tile, located at New York City Transit Central Park North–110th Street station (2, 3). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. © Maren Hassinger. Photo: Rob Wilson

“I lived in Egypt. I stayed in Egypt, and I was among brothers and I felt the spirit of brotherhood,” declared the political and religious leader Malcolm X in 1963. Situated on the subway platform at the Central Park North (110th St) station, these words become a central feature of Maren Hassinger’s 1998 multipart mosaic installation, Message from Malcolm. In a powerful act of ancestral reclamation, Malcolm X visited Egypt three times; he made subsequent speeches that related his experience of fellowship with Egyptian nationals and expressed his conviction that ancient Egypt was proof of a noble ancient Black civilization.

In Message from Malcolm, Hassinger harnesses his words to convey a message of kinship and equality to the community in Harlem, which the artist calls home. The curling cursive text of X’s words are set against richly colored gold and blue tiles, which sharply contrast the muted red columns and worn wooden seats surrounding the installation, infusing the mundane with a sense of majesty. The artist said of the commission, “Here the idea of power, leadership, and spiritual support are linked. Malcolm X believed that we as African Americans have the power to determine our destinies. This station is a reminder of that truth.”[7]

Left: Maren Hassinger (American, born 1947). Twelve Trees #2, 1979. Galvanized wire rope, originally installed along Mulholland Drive off-ramp, San Diego Freeway, Los Angeles. Image courtesy the artist and Susan Inglett Gallery. © Maren Hassinger. Right: Detail of Message from Malcolm, 1998. Mosaic tile, located at New York City Transit Central Park North–110th Street station (2, 3). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. © Maren Hassinger. Photo: Trent Reeves

A series of self-referential glyphs appear as decorative motifs throughout Message from Malcolm, beginning along the stairwell that leads to the subway’s turnstiles. Their forms recall the spindly shapes of Hassinger’s signature wire-rope installations, such as her Number series (1973) and Twelve Trees #2 (1979). The artist first encountered the material in a junkyard in the early 1970s when she was studying for her master’s degree in fiber structure at the University of California, Los Angeles. She experimented simultaneously with installation, sculpture, and performance alongside other Los Angeles–based artists, including Conwill—most of whom belonged to the loose collective of Black artists known as Studio Z. In her early sculptures, she utilized wire rope to explore the complicated relationship between the industrial and organic, identifying the latter as being overrun by the former. Through the simplified symbols across Message from Malcolm, the piece hints at the subsequent tension between cultural advancements (including transportation) and the nature they degrade. Like Conwill’s cryptic markings in The Open Secret, Hassinger’s mosaic pictograms evoke the advanced, code-like system of Egyptian hieroglyphs, yet resist verisimilitude.

Terry Adkins (American, 1953–2014). Detail of Harlem Encore, 1999. Aluminum panels, located at Metro North Railroad Harlem–125th Street station. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. © Terry Adkins. Photo: Trent Reeves

Throughout the 1990s, out of frustration with the gallery system’s emphasis on production and sales, Terry Adkins created installations of found materials in abandoned buildings slated for demolition in the Dumbo neighborhood of Brooklyn.[8] The MTA commission, however, offered a permanent solution that would remain outside the realm of commodification. Unveiled in 1999 at the Harlem–125th Street station of the Metro-North Railroad system, the two aluminum relief panels that comprise Adkins’s Harlem Encore reflect the artist’s sustained practice of assembling items with personal and historical resonance. Here, he merges allusions to his religious upbringing and later participation in jazz circles as a saxophonist with iconography derived from the Harlem Renaissance.

Raised Catholic and with a Baptist reverend grandfather, Adkins spent much of his childhood in churches. “This early exposure to an architectural space that was made for ceremony as well as contemplation had a profound effect on me,” he reflected in 2012.[9] The symmetry and doubling of Harlem Encore’s two panels gesture toward the architectural features of the pristine and ordered church interiors of his youth. An affinity for music also reverberates through the installation, its title suggesting a repeated performance—one of innovation, artistry, and uplift for Harlem residents and visitors alike.

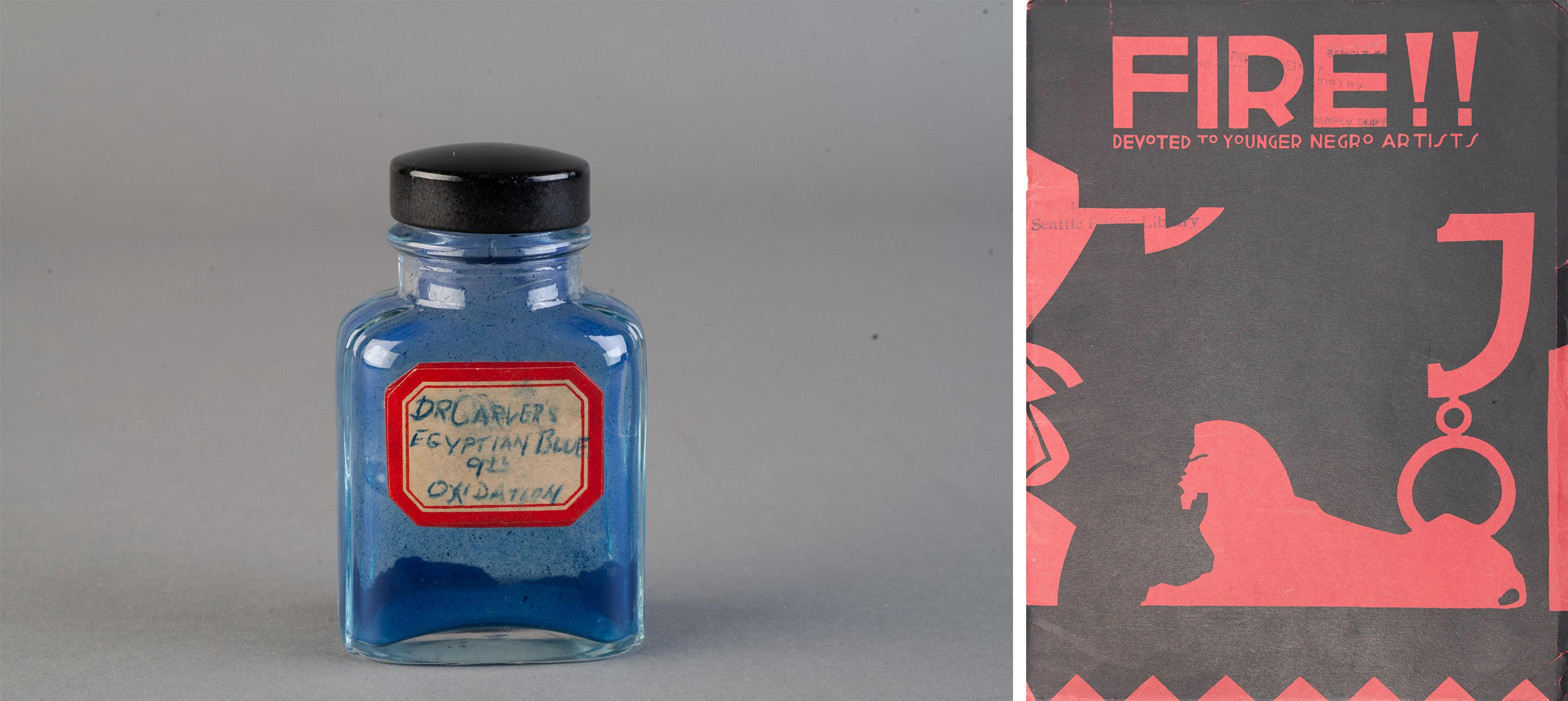

Left: George Washington Carver (American, ca. 1864–1943). Dr. Carver’s Egyptian Blue 9th Oxidation, 1930s. Glass bottle containing pigment. Special Collections and University Archives, Iowa State University Library, Ames. Right: Aaron Douglas (American, 1899–1979). Cover of Fire!! A Quarterly Devoted to the Younger Negro Artists, November 1926. Collection of Walter O. and Linda Evans. © 2024 Heirs of Aaron Douglas / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Image courtesy Walter O. Evans Foundation for Art and Literature

With Harlem Encore, Adkins develops links between two great forebears of the African diaspora, George Washington Carver and Aaron Douglas. The blue of the painted background and tinted lights is a color Adkins returned to throughout his practice, drawn to its celestial references in the Catholic tradition and its connection to Carver, a prolific agricultural scientist and artist. In 1923, a year after the richly painted tomb of the ancient Egyptian pharaoh Tutankhamun was rediscovered, Carver submitted a U.S. patent application for a pigment he called “Egyptian Blue.”[10] Viewed in the context of Adkins’s final series, which directly cites Carver alongside French artist Yves Klein, who developed the pigment International Klein Blue, the deployment of blue in Harlem Encore can likewise be understood as an allusion to ancient Egypt. In the foreground, the stylized sphinxes that bookend pictorial reliefs explore African ancestry by way of Aaron Douglas, a painter and illustrator who was a major proponent of ancient Egypt as a creative source for the Harlem Renaissance. Adkins was mentored by Douglas while at Fisk University in the early 1970s.[11] Here, he replicates the elder artist’s 1926 cover illustration for Fire!! A Quarterly Devoted to the Younger Negro Artists, a magazine published by a cohort of Black writers that included Zora Neale Hurston and Langston Hughes, among others. Made in an effort to “right historical wrongs,” as Adkins put it, Harlem Encore affirms ancient Egypt as a lasting source of inspiration and identification for Black artists and cultural figures.[12]

From passageways to platforms, the sites that host The Open Secret, Message from Malcolm, and Harlem Encore are not final destinations but rather spaces of locomotion, connection, and transition. Mimicking the function of these built environments, the installations forge a series of transhistorical linkages with ancient Egypt as their starting point. As curator and writer Mia Matthias asserts, “Ancient Egypt becomes a vessel for building personal and collective mythologies and a self-reflexive mythology for Black people speaking to each other across time and space.”[13] The works function as distinctive yet related time capsules that invite Harlem residents, commuters, and visitors into the valuable histories they carry.

Notes

[1] Sandra Bloodworth and William S. Ayres, New York’s Underground Art Museum: Expanding along the Way (New York: The Monacelli Press, 2014), 15.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Tracy Fitzpatrick, Art and the Subway: New York Underground (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2009), 230.

[4] Susan Krane, Art at the Edge: Houston Conwill: The New Cakewalk (Atlanta, Georgia: High Museum of Art, 1989), 9.

[5] Bloodworth and Ayres, New York’s Underground Art Museum, 60.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Bloodworth and Ayres, New York’s Underground Art Museum, 208.

[8] Stephanie Weissberg, “Resounding,” in Terry Adkins: Resounding, ed. Heather Alexis Smith (St. Louis, MO: Pulitzer Arts Foundation, 2020), 22.

[9] Heather Alexis Smith, ed., Terry Adkins: Resounding (St. Louis, MO: Pulitzer Arts Foundation, 2020), 12.

[10] “Something Out of Nothing is Negro’s Gift to Science,” Virginia Register, November 2, 1932.

[11] Akili Tommasino, Andrea Myers Achi, Makeda Best, Mia Matthias, et al. Flight into Egypt: Black Artists and Ancient Egypt, 1876-Now (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2024), 240.

[12] Bloodworth and Ayres, New York’s Underground Art Museum, 64.

[13] Mia Matthias, “‘We Are Both Myth’: Ancient Egypt and Opacity,” in Akili Tommasino, Andrea Myers Achi, Makeda Best, et al. Flight into Egypt: Black Artists and Ancient Egypt, 1876-Now (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2024), 51.