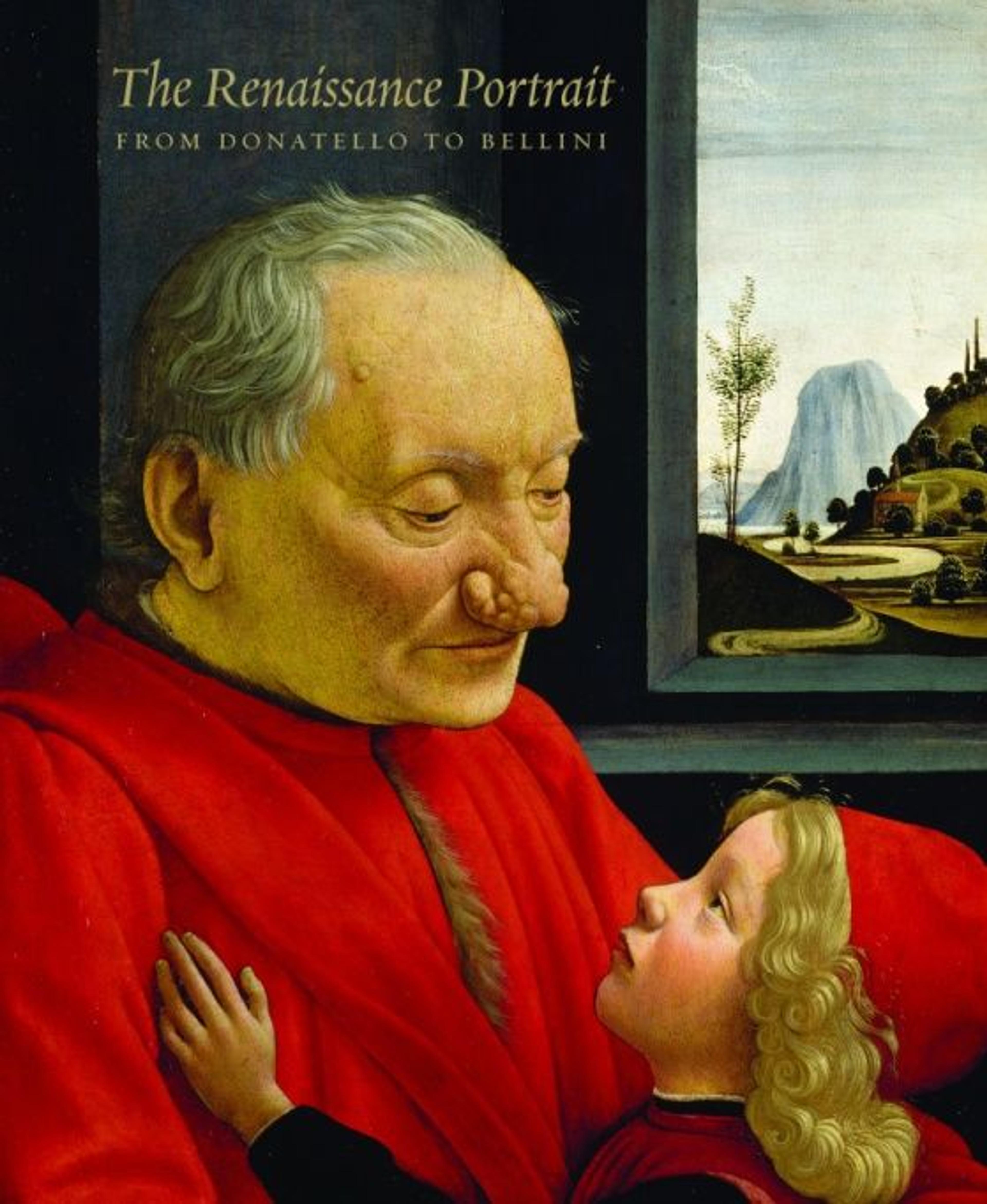

In conjunction with the exhibition, the Met recently published The Renaissance Portrait: From Donatello to Bellini, a 432-page hardcover catalogue with 275 full-color illustrations, available in The Met Store.

«In the words of the historian Jacob Burckhardt, fifteenth-century Italy was "the place where the notion of the individual was born." In keeping with this notion, early Renaissance Italy hosted the first great age of portraiture in Europe.» Artists working in Florence, Venice, and the courts of Italy created magnificent portrayals of the people around them—heads of state and church, patrons, scholars, poets, artists—concentrating for the first time on producing recognizable likenesses and expressions of personality.

Written by a team of international scholars, The Renaissance Portrait provides new insight into the early history of portraiture in Italy, examining in detail how its major art centers—Florence, the princely courts, and Venice—saw the rapid development of portraiture as closely linked to Renaissance society and politics, ideals of the individual, and concepts of beauty. More than 160 magnificent works, in media ranging from painting and manuscript illumination to marble sculpture and bronze medals, created by artists that include Donatello, Filippo Lippi, Botticelli, Verrocchio, Ghirlandaio, Pisanello, Mantegna, Giovanni Bellini, and Antonello de Messina, are illustrated and extensively discussed. With abundant style and visual ingenuity, these masters transformed the plain facts of observation into something beautiful to behold.

Botticelli (Alessandro di Mariano Filipepi) (Italian, Florence 1444/45–1510 Florence), Ideal Portrait of a Lady ("Simonetta Vespucci"), 1475–80. Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main. Image © U. Edelmann—Städel Museum/ARTOTHEK

Excerpts

No patron was pricklier about her own image than Isabella d'Este (1475–1539) . . . a portrait by Cosmè Tura had been sent to her prospective husband, Francesco Gonzaga, with a letter assuring him that it was not her looks but her "marvelous intellect and intelligence" that was most impressive. Isabella later complained to her husband that if she had had more to do with running the state then she would not have grown so fat, but a rare medal issued in celebration of her wedding already shows her to be a rather uncomely bride.

—From the essay "Portraiture at the Courts of Italy" by Beverly Louise Brown, independent scholar

As daughters, wives, and mothers, women were judged by another standard and are generally represented following a very different criteria…Many are in profile, emphasizing flowing contours and allowing for the appreciation of every detail of their finery and delicately delineated features, without any threat of suggesting an immodest or dangerous exchange of glances.

—From the essay "Understanding Renaissance Portraiture" by Patricia Rubin, Director of the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University and an authority on the art of Renaissance Florence

One of the most powerful motivating forces behind the rapid development of the art of portraiture in fifteenth-century Italy was a new sense of the individual human personality. Conversely, it is probably true that during the first century of its history, that development was often constrained by a political and social ethos that placed a higher value on the collective interests of the Venetian state than on individual self-expression. Before about 1500, autonomous Venetian portraits– including those of their greatest exponent, Giovanni Bellini–tended to be simple in pose, objective in treatment, and impassive in mood. All this changed with the advent of the generation of Giorgione, Lotto, and Titian.

—From the essay "The Portrait in Fifteenth-Century Venice" by Peter Humfrey, Professor at Saint Andrews University specializing in Renaissance Venice

Related Link

The Met Store