Francí Gomar (Spanish, active by 1443–died ca. 1492/3). Altar Predella and Socle of Archbishop Don Dalmau de Mur y Cervelló, ca. 1456–58. Alabaster with traces of paint and gilding, 107 x 183 x 26 1/4 in. (271.8 x 464.8 x 66.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Pierpont Morgan, 1909 (09.146)

«Last month, the recent season of Game of Thrones caused me to reflect on gruesome medieval images of the martyrdoms of Saint Lawrence and Saint Bartholomew, whose feasts are celebrated in August. This month, I turn to the depiction of two holy women whose feast days are in the fall: Saint Thecla (September 23 and 24) and Saint Catherine (November 25).»

I am predictably squeamish when it comes to artists' depictions of violence against women; it's far too easy for me to imagine their pain.

So, I am relieved that The Met Cloisters' alabaster altar from the archbishop's chapel at Saragossa presents an abbreviated, remarkably tame legend of Saint Thecla. Notwithstanding the lurid, graphic details of her legend, the patron of the altar carvings, Don Dalmau de Mur y Cervelló (died September 12, 1456), clearly chose to have the sculptor, Francí Gomar (active by 1443–ca. 1492/3), present only the crucial bookends of the story without excess drama.

Francí Gomar (Spanish, active by 1443–died ca. 1492/3). Altar Predella and Socle of Archbishop Don Dalmau de Mur y Cervelló (detail, left: Saint Thecla survives being burnt at the stake; right: Saint Thecla listens to Saint Paul's sermon), ca. 1456–58. Alabaster with traces of paint and gilding, 107 x 183 x 26 1/4 in. (271.8 x 464.8 x 66.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Pierpont Morgan, 1909 (09.146)

Standing at her window one day, Thecla, a young noblewoman, happened to hear Saint Paul preaching. The alabaster carving brings the scene to life in charming detail. In the section pictured above-right, Theca listens intently to Paul's words, arms propped on a pillow at her window. Other members of the crowd assembled outside are less attentive: one scratches his chin, another snoozes, and a third looks away.

However, omitted from the altarpiece are details of how Saint Paul's words and Thecla's emerging, unflagging sense of mission would get her into trouble. Overwhelmed by the power of Paul's sermon, Thecla determined to be a Christian, embracing chastity in flagrant defiance of her fiancé and her mother. She baptized herself and became celebrated as a preacher and healer.

Some 40 surviving manuscripts in Greek, Syriac, Coptic, Armenian, and Latin detail Thecla's heroic adventures.[1] This was a story ripe for illustration: lions, bears, and bulls were set upon her to no avail. Gomar's alabaster carving presents only the failed attempt to burn her at the stake (visible above-left); the fire is miraculously quenched and all stand in amazement.

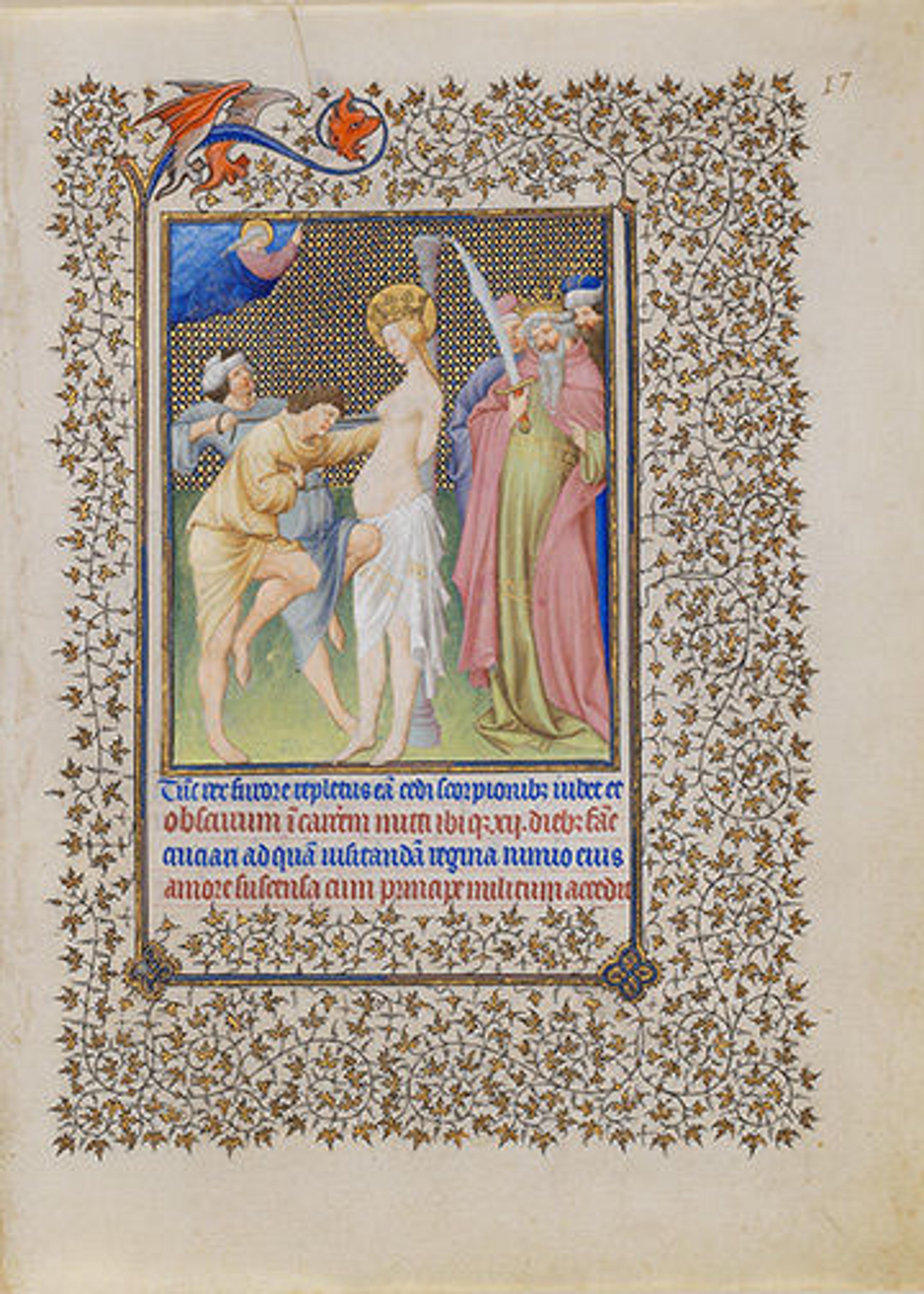

Left: The Limbourg Brothers (Franco-Netherlandish, active France, by 1399–1416). The Belles Heures of Jean de France, duc de Berry (detail, folio 17 recto), 1405–1408/09. Tempera, gold, and ink on vellum, 9 3/8 x 6 x 11/16 in. (23.8 x 17 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1954 (54.1.1)

By contrast, in images of Saint Catherine from The Met Cloisters' Belles Heures made for Jean, duc de Berry, the Limbourg Brothers present an elaborate narrative, deliberately and provocatively heightening the inherent drama of the story.

The Latin text concerning the flaying of Saint Catherine recounts how "The king, filled with fury, ordered her to be given up to scourging, and sent her to a dark prison and tortured her there with hunger for twelve days." How would one depict a hungry soul beaten in the dark? It's far more compelling to bring brilliant color to bear, contrasting the blanched naked torso of the passive woman with the raw aggression of powerful men. The setting is benign, even beautiful—no mud or soiled clothes here—but this is raw, prurient imagery.

Right: The Limbourg Brothers (Franco-Netherlandish, active France, by 1399–1416). The Belles Heures of Jean de France, duc de Berry (detail, folio 15 recto), 1405–1408/09. Tempera, gold, and ink on vellum, 9 3/8 x 6 x 11/16 in. (23.8 x 17 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1954 (54.1.1)

Set in perfect counterpoint to the rough images of Catherine's suffering are those that celebrate inspiration in the legend of Saint Catherine. Like Saint Thecla before her, Catherine is distinguished by her wisdom and a willingness to speak truth to power. Predictably, these are also the qualities that set the authorities against her, and they are celebrated emphatically in the Belles Heures.

In the first illumination of the cycle, Catherine sits peaceably in her private library. This point of transformation is equivalent to the image of Saint Thecla listening to Saint Paul's sermon. Yet, she does not hear a live sermon; rather, she reads. She is guided by Moses and the Law, images of whom are depicted in the room. Eight more books are on her bookstand. This is no tidy shelf; volumes of red, green, and pink lie atop one another, as if in active use, just set down. Reinforcing the image, the Latin text at Catherine's feet proclaims that this beautiful daughter of a king is "versed in the liberal arts."

The Limbourg Brothers (Franco-Netherlandish, active France, by 1399–1416). The Belles Heures of Jean de France, duc de Berry (detail, folio 15 verso), 1405–1408/09. Tempera, gold, and ink on vellum, 9 3/8 x 6 x 11/16 in. (23.8 x 17 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1954 (54.1.1)

In the next scene, Catherine defies and confounds the pagan emperor, who tries to force her to worship a false idol, "by the depth of her remarkable learning and by her eloquence." Elegantly, she turns her head away from the false god unworthily set on a gilded pedestal.

Right: The Limbourg Brothers (Franco-Netherlandish, active France, by 1399–1416). The Belles Heures of Jean de France, duc de Berry (detail, folio 15 recto), 1405–1408/09. Tempera, gold, and ink on vellum, 9 3/8 x 6 x 11/16 in. (23.8 x 17 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1954 (54.1.1)

Catherine then ramps things up even more, standing up to 50 learned men summoned by the emperor, winning them over "by the force of her arguments." The consequence will be martyrdom.

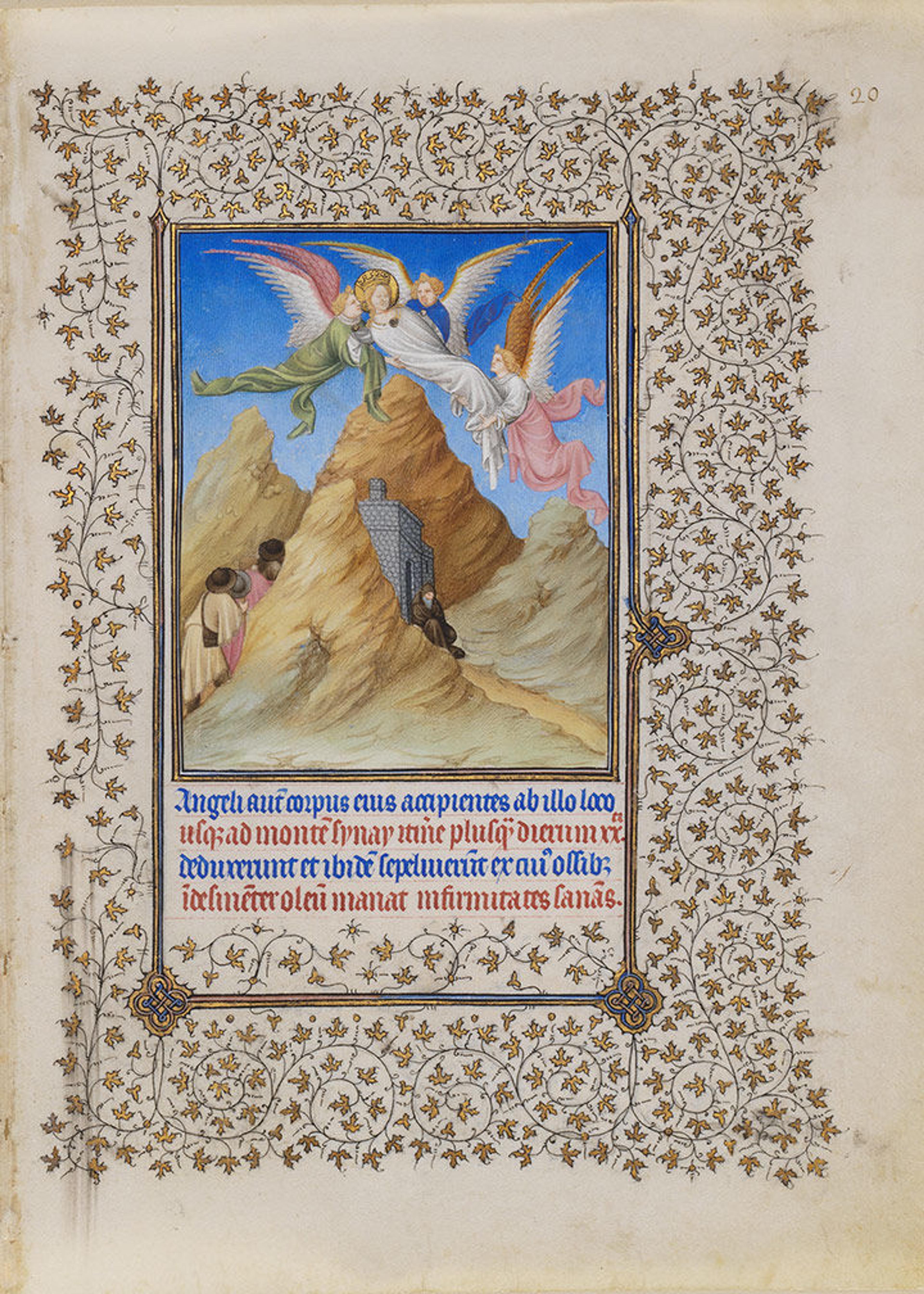

The false gods would appear to have won. But the manuscript—and, by extension, the creed of the powerful prince Jean de Berry, for whom it was created—argues otherwise, proclaiming Saint Catherine to be the one who ultimately triumphs, carried off by angels, and worthy of praise for all eternity.

The Limbourg Brothers (Franco-Netherlandish, active France, by 1399–1416). The Belles Heures of Jean de France, duc de Berry (detail, folio 20 recto), 1405–1408/09. Tempera, gold, and ink on vellum, 9 3/8 x 6 x 11/16 in. (23.8 x 17 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1954 (54.1.1)

Note

[1] Those interested in these tales should see: Stephen J. Davis, The Cult of Saint Thecla: A Tradition of Women's Piety in Late Antiquity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001).

Related Content

Read Barbara Drake Boehm's blog post "Broken Bodies: Violence in Art and Game of Thrones."

Steven Janke, "The Retable of Don Dalmau de Mur y Cervelló from the Archbishop's Palace at Saragossa: A Documented Work by Francí Gomar and Tomás Giner," The Metropolitan Museum of Art Journal, 18 (1983).