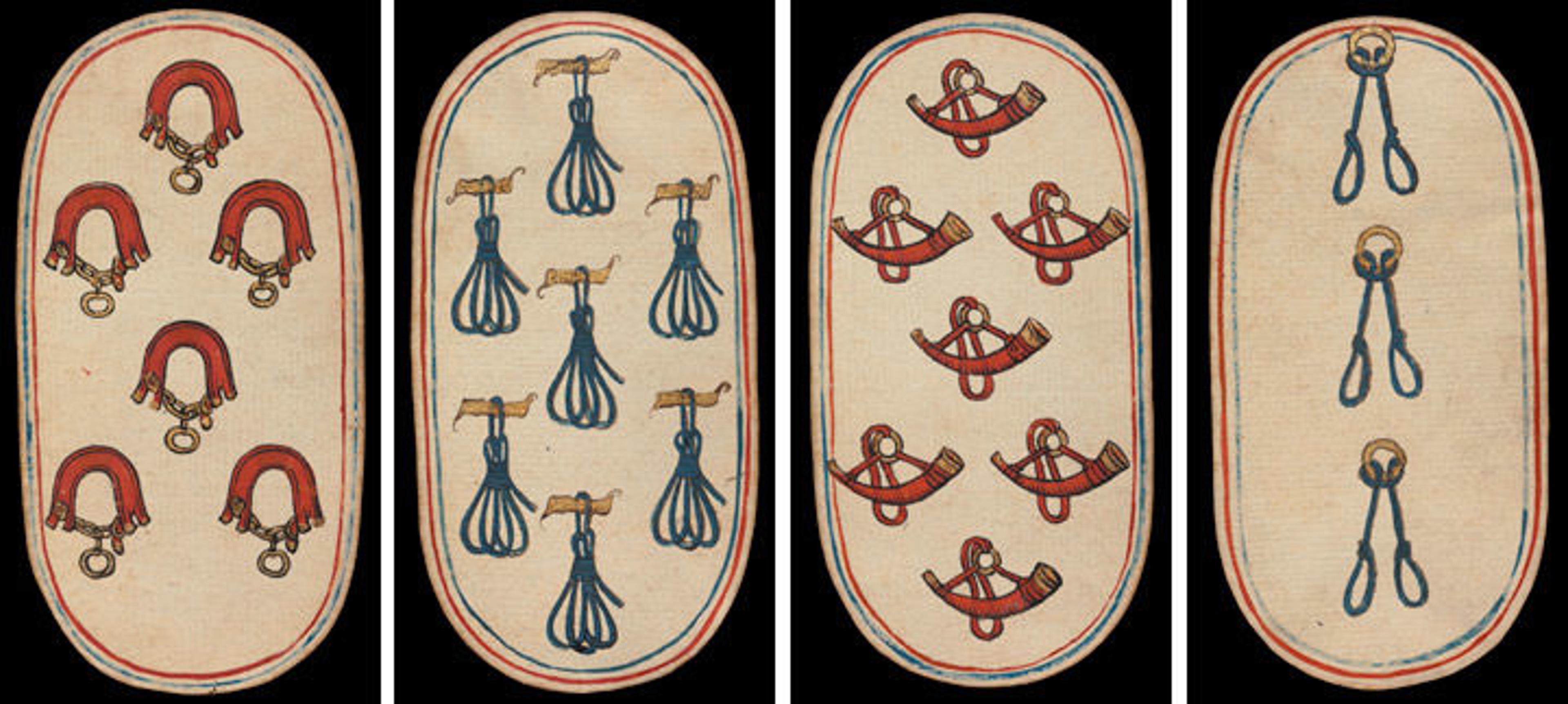

6 of Collars, 7 of Tethers, 7 of Horns, and 3 of Nooses, from The Cloisters Playing Cards, ca. 1475–80. Made in Burgundian territories. South Netherlandish. Paper (four layers of pasteboard) with pen and ink, opaque paint, glazes, and applied silver and gold; 5 3/16 x 2 3/4 in. (13.2 x 7 cm); The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 1983 (1983.515.1–.52)

«Largely based on style, The Cloisters Playing Cards have been attributed to the Netherlands under the rule of the dukes of Burgundy and dated to about 1475 to 1480. However, the deck is more similar to the German packs discussed in this series than to French ones. Like the German decks, the suit symbols pertain to the hunt, but here they are all inanimate: Collars (for dogs), Tethers (for hounds), Horns (for hunting), and Nooses (for suspending birds or small game from the belt), all of which can be seen in use by a huntsman and his white hound in the center foreground of the calendar page for August in the Grimani Breviary.»

Right: Gerard Horenbout (1465–1541). Grimani Breviary, calendar page for August, A Hunting Party Sets Out (detail), ca. 1510–20. Netherlandish, ghent or Bruges. Tempura on vellum. Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, Venice

As with the German packs, the relative value of the suits is unknown. The face cards consist of a king, queen, and single knave, followed by pip cards 10 through 1. The suit of the face cards is denoted by the appropriate symbol that each figure wears, carries, or has emblazoned on his or her costume, except for Tethers, which are repeated four times in the background. The values of the pip cards are indicated by the appropriate repetition of the symbol, as they are in The Courtly Hunt Cards.

The face cards were produced entirely freehand. The outlines of the figures were sketched in with both score marks made with a stylus and charcoal underdrawing, some traces of which can still be detected. The figures were then filled in with pen and ink and colored with typical medieval pigments bound in organic glue, glair (a sizing made of egg white and vinegar), or gum arabic. Glazes were used extensively to finish the figures, and gold and silver leaf applied over an organic adhesive was employed liberally throughout.

The elaborate, magnificent costumes of the kings and queens, which display abundant amounts of ermine and bejeweled trim, gold embroidery, and substantial gold necklaces with gem-studded pendants, are perhaps the most striking aspect of the face cards. The knaves wear the less opulent costumes appropriate to their varying stations: jester, herald, foot soldier, and huntsman. Rather than as a record of some specific time or event, the royal figures in all their sartorial splendor function as fashion plates representing the middle and later decades of the 15th century.

King, Queen, and Knave of Nooses, from The Cloisters Playing Cards

A number of details seem odd or excessive even by the standards of Burgundian court fashion. The short doublet with open-seam sleeves worn by the King of Nooses, for example, is a costume usually identified with a courtier rather than a king. By the late Middle Ages, the emblazoned tabard of the King of Collars was generally worn by a knight over his armor or was the garb of a herald and not the king.

King, Queen, and Knave of Collars, from The Cloisters Playing Cards

It is difficult to discern whether these sartorial oddities reflect the excesses of Burgundian court fashion or whether they are deliberate exaggerations to lampoon those immoderations. In any event, these embroidered devices identified the wearer with the master he served and were generally worn by courtiers and not by the lord. The extravagant gold-embroidered devices on the leggings of the King of Tethers and the King of Collars as well as on the leggings and sleeves of the Knave of Nooses were considered eccentric.

King, Queen, and Knave of Tethers, from The Cloisters Playing Cards

These court figures in their lavish dress displaying ordinary equipment of the hunt as if it were regal appurtenances might have been intended to parody the extravagances of the Burgundian court. Unlikely a noble commission, The Cloisters Playing Cards may have been commissioned by a well-to-do member of the mercantile class who felt secure enough in his burgeoning social status to hazard satirizing one on the wane. If this was the case, the lampoon was provident, for the death of Charles the Bold, the last of the Burgundian dukes, on the battlefield in 1477 heralded the demise of the court as it had been known.

Related Link

Met Blogs: View all blog posts related to this exhibition.

1983.515.1–.52