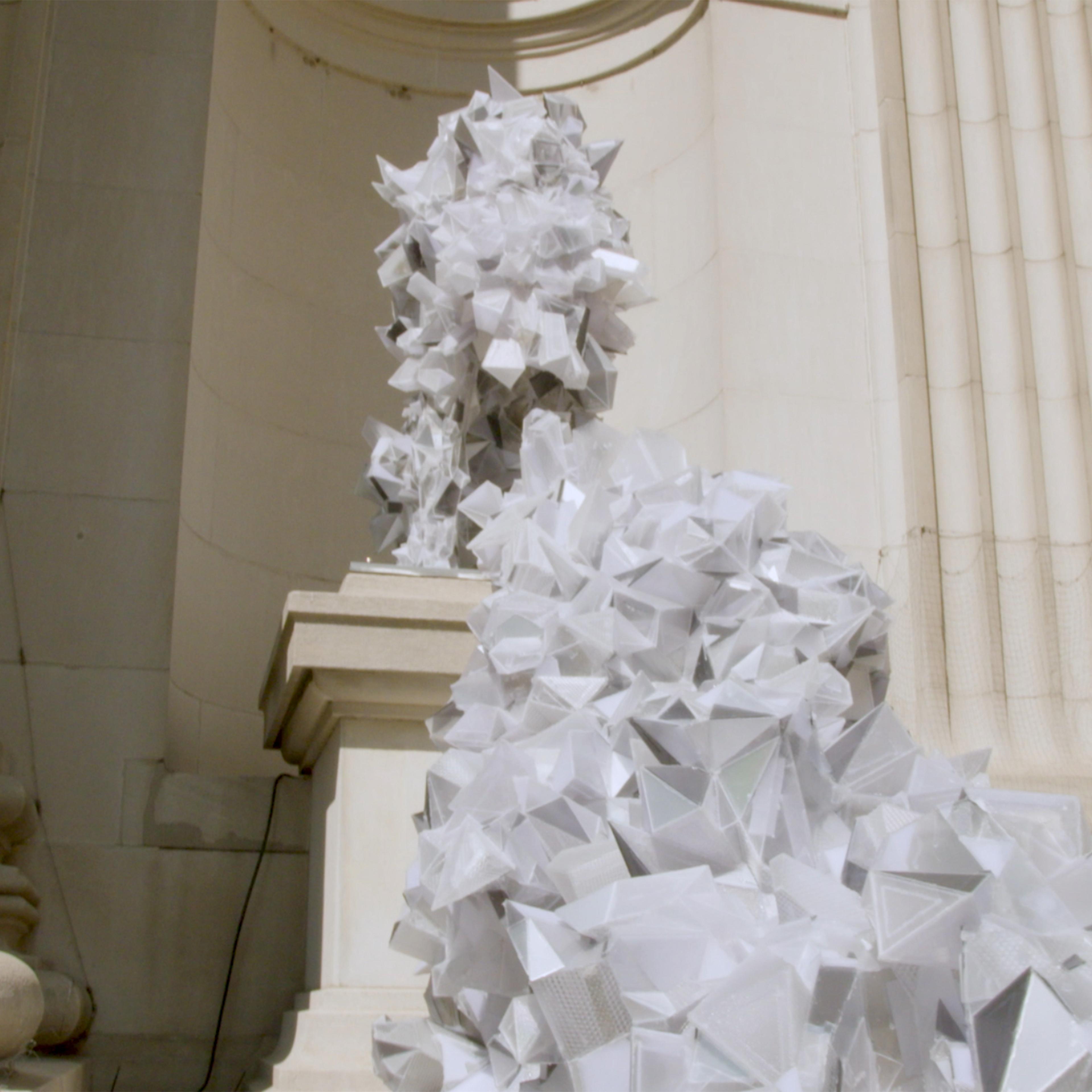

When I saw Lee Bul’s Long Tail Halo (2024), I saw it in media res, in metamorphoses, like an opened nesting doll of guardians. I wanted to answer her narrative capacity by describing the sculptures, moving back and forth between illustration and association. This was to try to pay homage to the way her figures could shift between past and future, human and animal, organic and inorganic, public and personal, mythical and real—all depending on perspective.

Long Tail Halo: The Secret Sharer III, 2024. Stainless steel, polycarbonate, acrylic, polyurethane, dimensions variable Part A (top): 154(h) x 80(w) x 163(d) cm - Upper Part B (bottom): 217(h) x 95(w) x 245(d) cm - Lower. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, © Lee Bul. Courtesy of the Artist

This poem echoes the dual structure of the inner and outer figures, but in the spirit of the work, transforms it into something unexpected. The first part of the poem responds to the way these figures seem to evolve before our eyes—a chance for a better life. A sea urchin felt like a fitting analogy since they experience a rebirth—growing their juvenile self inside their larval forms, and, when the time and tide are right, turning inside out. I saw this in The Secret Sharer II and The Secret Sharer III, all spiky explosions of fang-like fur, suddenly gifted with speech. I saw this new protective layer echoed in the compelling fortresses of CTCS #1 and CTCS #2.

Left: Lee Bul (South Korean, b. 1964). Long Tail Halo: CTCS #1, 2024. Stainless steel, ethylene-vinyl acetate, carbon fiber, paint, polyurethane, 275(h) x 127(w) x 162(d) cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, © Lee Bul. Courtesy of the Artist. Right: Lee Bul (South Korean, b. 1964). Long Tail Halo: CTCS #2, 2024. Stainless steel, ethylene-vinyl acetate, carbon fiber, paint, polyurethane, 268(h) x 127(w) x 111(d) cm. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, © Lee Bul. Courtesy of the Artist

The second part of the poem took more time. I looked up at CTCS #2 for a while. My mind filled in what should have been a head but instead was a wing. CTCS #1 had the same transcendent effect: it evoked the story of Pegasus, emerging from the neck of Medusa—the winged horse rising from the mostly human figure. There was the hope of Long Tail Halo in that image. Seeing the human-like and dog-like figures frozen, but in motion, colossuses between columns, there again was Medusa, how she and her Gorgon sisters turned any being who looked at them to stone. But after looking, and looking again, the story now seemed an act of mercy.

The spines of the sea urchin and the snakes of Medusa’s hair were a happy coincidence.

"The costs" by Hannah Sanghee Park

The costs

1: From a sea urchin turned inside out

Finally—

adrift after

draft after draft of

a life lived larval—

the arrival

of the more viable

living thing.

Body livable.

Less altricial.

Innards turned skin;

skin turned spines.

Little obliteration

to a better iteration

in time.

2: To Pegasus, for Medusa

You see,

stone from skeleton, skeleton formed by stone. Dog from geode,

guts quartz. Try to understand where she’s coming from.

Turning all that is animal mineral: all the better to endure

the violence. Look, her glance is benevolence. Here, without

a head wired in frenzy, frozen, no one can hurt you, and you

can’t hurt them in return. Gargoyles, transformed by Gorgons:

loyal guardians. What I wouldn’t do for you. What I did.

I can be chimeric when beyond bone, behind armor, bounded

by hounds. I can evolve you, finally. Here are the double helixes,

twisting upward, smooth and scarred. Here is a future where

you are protected: you too can have edges, the soft made sharp,

body and head vestigial. Please, at the end of all this, be wings.

Younger, I always worried about earthquakes. Kits and drills

guaranteed nothing. So it seemed the solution was to somehow

shrink my family and put them in a locket. Carry them to safety.

And don’t I still wish for the miniature, how you could form

in me from only the best of me. And still wish the improbable,

the idea that the neck gives way to wings. To lift you out of here,

should it spare you from my mistakes. To show mercy, but not be at

the mercy of the world. And the difference is to yes, love with all you have,

but still love yourself enough to survive it.