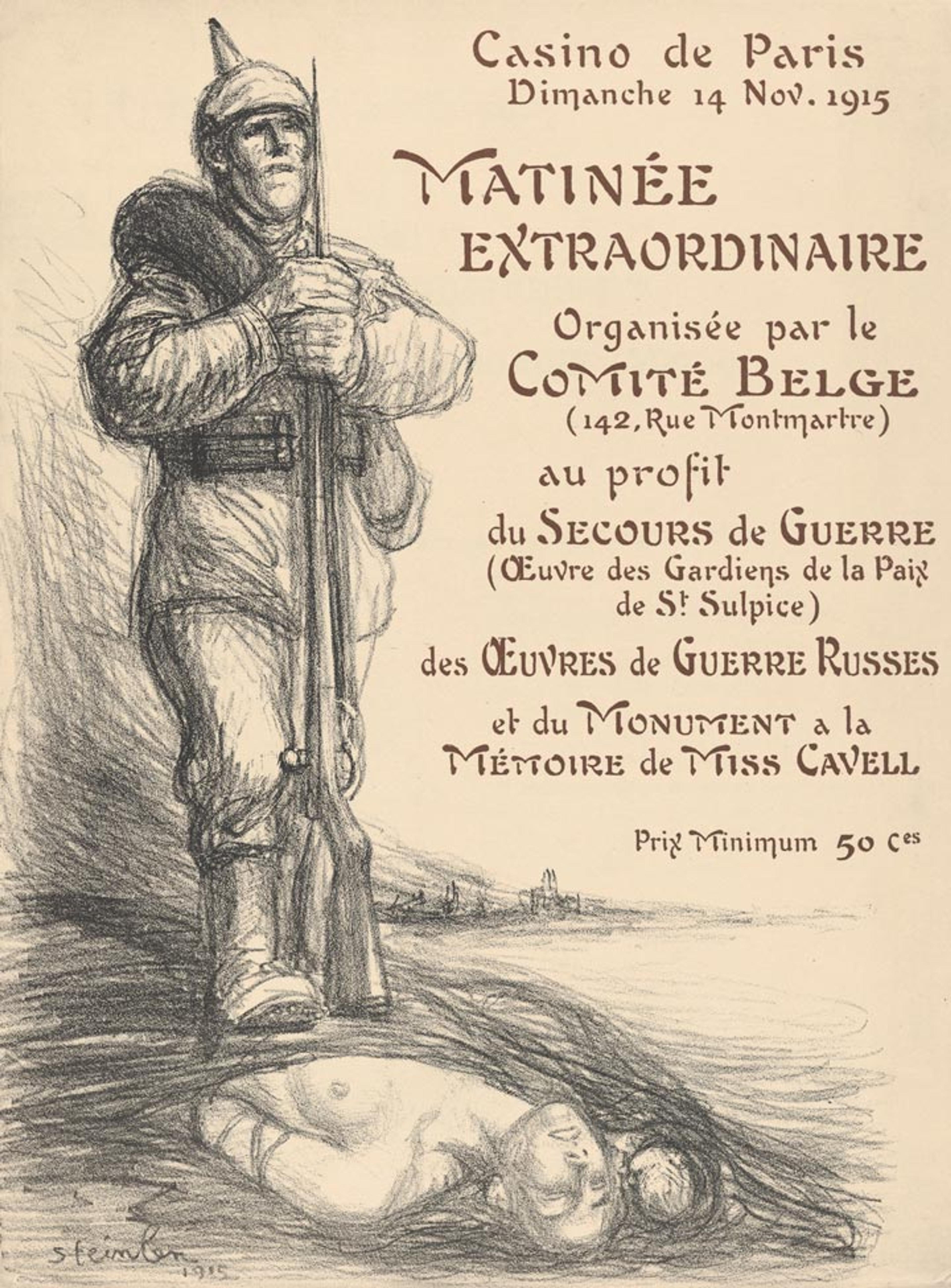

Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen (French [born Switzerland], 1859–1923). Program for the Matinée Extraordinaire, Casino de Paris, 1915. Lithograph, sheet (folded): 14 15/16 in. x 11 in. (38 x 28 cm); sheet (open): 14 15/16 x 22 1/16 in. (38 x 56 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Bella C. Landauer, 1926 (26.28.83)

«One of the first artists that visitors encounter upon entering the exhibition World War I and the Visual Arts is Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen. The three works on display—Mobilization, The Exodus, and Program for the Matiné Extraordinaire—represent the range of imagery Steinlen produced during wartime and a significant shift in the artist's practice. Like many of his vanguard contemporaries, Steinlen's artistic focus in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was centered on leftist social commentary. However, as the devastation of World War I emerged across Europe, the urgency of the human effects of war moved to the forefront of his priorities.»

Born in Lausanne, Switzerland, Steinlen moved to Paris in 1881 at the age of 21. He settled in Montmartre, an area in the north of the city where many ex-patriots, artists, and working-class people lived. Following the 1881 lifting of censorship in France and the passing of the Law on the Freedom of the Press, the production of politically focused artistic and literary ephemera flourished. From journals, periodicals, and newspapers to party invitations and public posters, the visual and literary arts quickly flooded the city with social discourse.

This suited artists like Steinlen perfectly. Though the artist created a number of paintings in his lifetime, it does not compare to the endless volume of politically focused ephemera he devoted his career to making. Steinlen was a socialist and a relentless supporter of working-class rights. Upon his move to Montmartre, the artist quickly engaged with the leftist community in France. He regularly contributed to the art-criticism periodical Gil Blas, the leftist satire journal Le Rire, the Marxist periodical Le Chambard Socialiste, and the anarchist paper La Feuille, as well as other publications and novels, often without compensation.

Through illustrating and printmaking, Steinlen aimed to communicate the chronicles of the working class as directly as possible, as he believed that understatement would affect the clarity of his argument. Since these widely circulated publications were part of a more democratic dissemination and reception of art, he viewed each of his works as a tool of resistance against oppression. This approach put his art in the hands of the individuals and environs he was concerned with—both artistically and socially—challenged traditional artistic hierarchies, and empowered the working class.

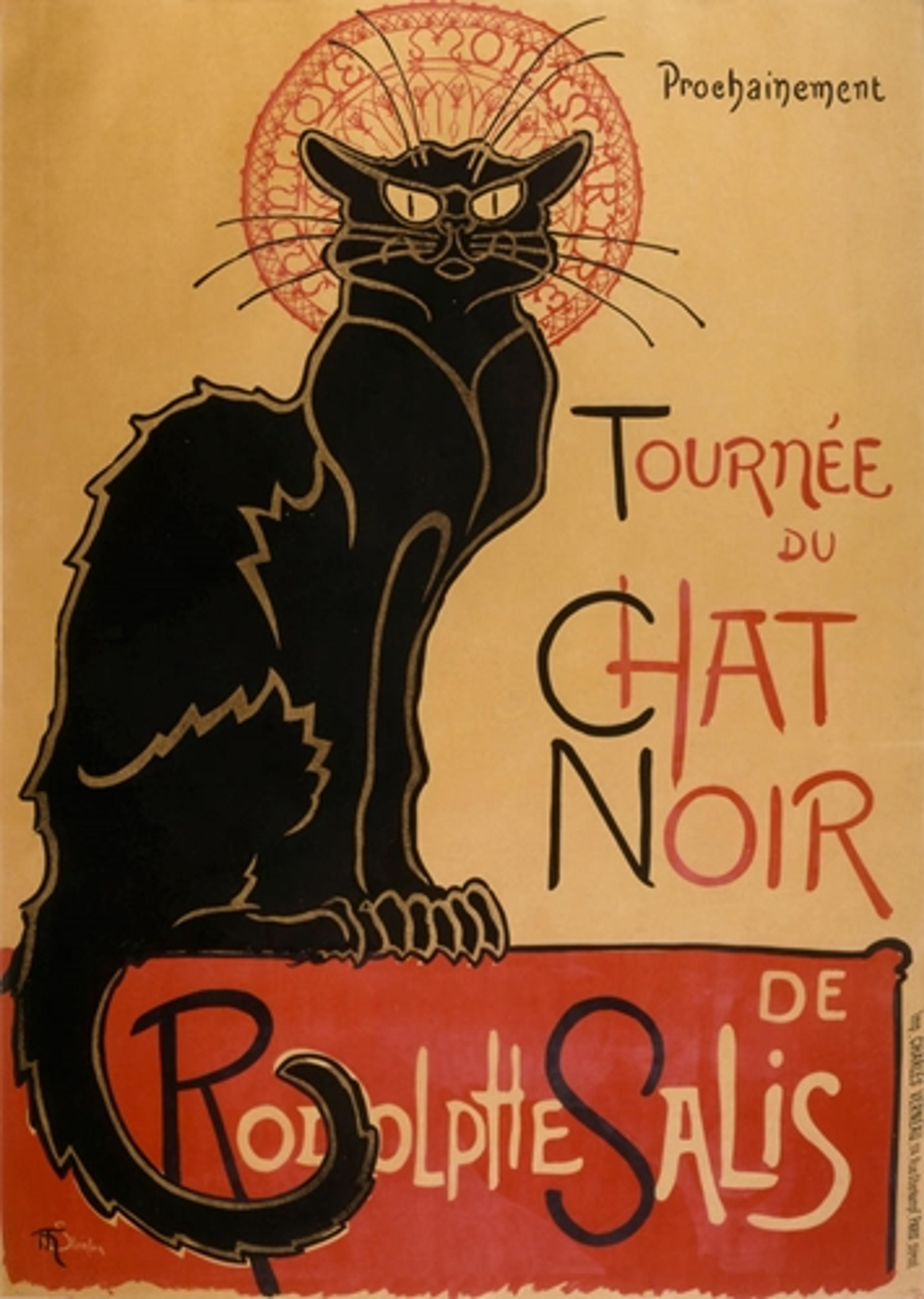

Steinlen became best known for his lithographic posters from the 1890s. Local Montmartre café concerts such as the famous Le Chat Noir would host provocative performers whose songs would engage in working-class narratives. It was there that Steinlen met Aristide Bruant, a singer who would influence the artist's work and politics, and serve as a frequent subject in his work.

Left: Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen (French [born Switzerland], 1859–1923). Tournée du Chat Noir de Rodolphe Salis, 1896. Chromolithograph, 53.5 in. x 37.76 in. Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University (77.050.003). Image via Wikimedia Commons

The two would go on to collaborate for many years, and it's clear to see why the performer would interest Steinlen: Bruant's performances exemplified the socialist priorities with which Steinlen was concerned. Singing in Argot, Bruant would meditate on the lives of local laborers while making fun of the bourgeois clientele in the audience. Parisians of all castes would be found together in these social spaces, and not only were they receptive to the scathing critiques about capitalism that Bruant expressed, they desired them. It is clear, then, to understand why Steinlen designed so many posters for this café concert, including his canonized Tournée du Chat Noir.

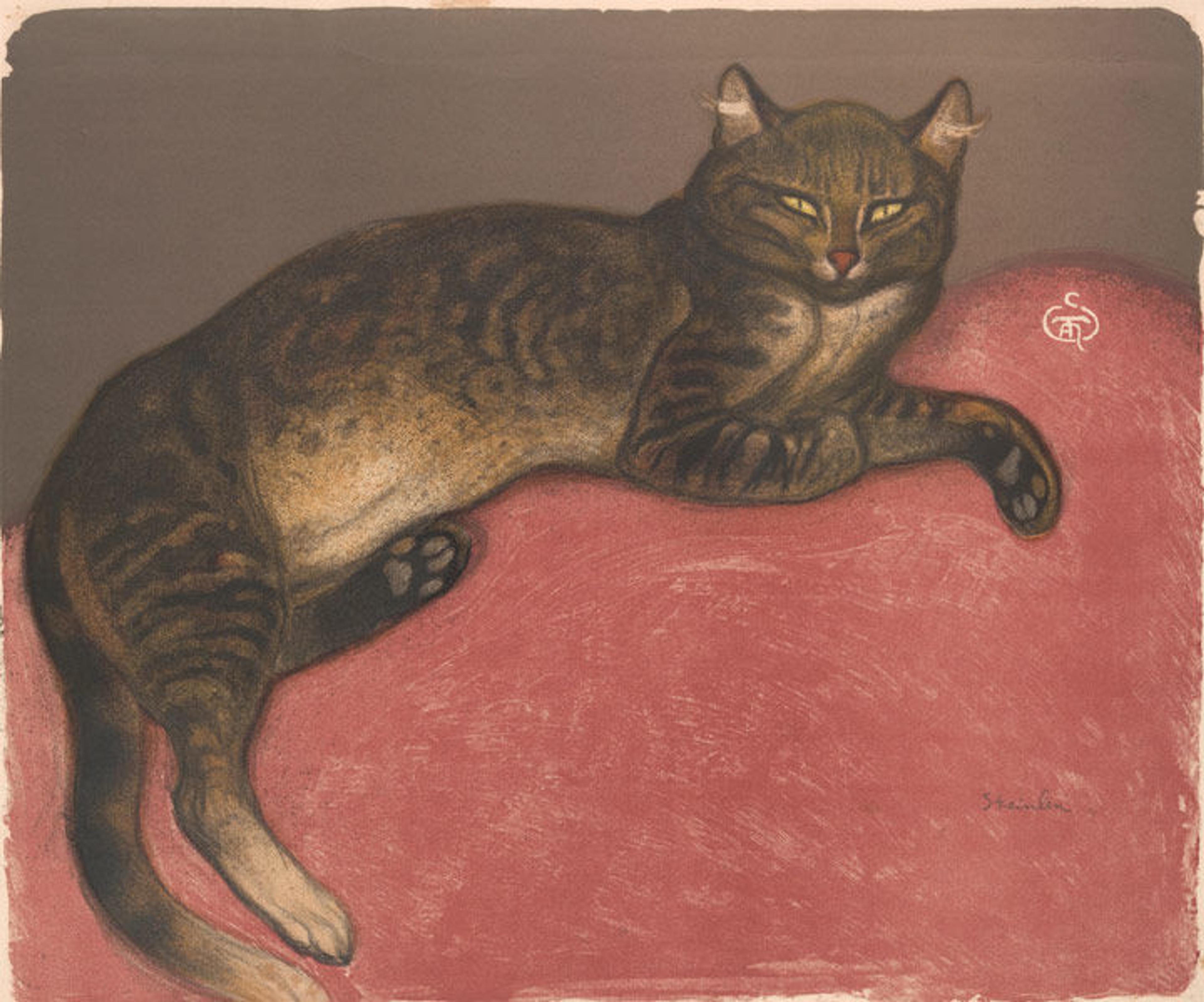

For anyone who has a sense of Steinlen's oeuvre, it is evident that cats were an important subject for him. The artist had affection for the animal, and was known to feed dozens of local cats in Montmartre. In many cases, cats appear in his advertising posters such as Lait pur Sterilisé, which also featured his daughter, Colette. However, he also produced an immense number of drawings and prints of cats in moments of leisure.

Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen (French [born Switzerland], 1859–1923). Winter: Cat on a Cushion, 1909. Color lithograph, sheet: 20 x 24 in. (50.8 x 61 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1950 (50.616.9)

Why the focus on cats? At the time, cats were symbolic of bohemia and, more specifically, bohemian women. The fact that many Parisian cats lived in Montmartre, free of bourgeois domestication, was perceived as a metaphor for modern bohemia, or the refusal of bourgeois social norms of that time. Steinlen perhaps most assertively and humorously represents the cultural presence of cats in Montmartre through an allegorical painting from 1905, The Apotheosis of the Cats of Montmartre. In contrast to his works that critiqued capitalism and narrativized working-class plights, Steinlen used works like these to explore the potentials of bohemian life unobstructed by capitalist Paris.

Steinlen's concern with the working class and marginalized populations was a theme he carried through his entire career. However, the outbreak of World War I necessarily altered the artist's subject matter, as it did for many of his contemporaries such as Jean-Louis Forain and Auguste Rodin, two artists also represented in World War I and the Visual Arts. Steinlen became artistically concerned with communicating the everyday experiences and human effects of war. The subjects in his work remained the same in many ways—women, children, the impoverished—but expanded into resting soldiers, displaced people, orphans, and those killed in battle. He generally steered clear of battle scenes and the narratives of political leaders, drawing attention to the multifarious devastations of what many considered a senseless war.

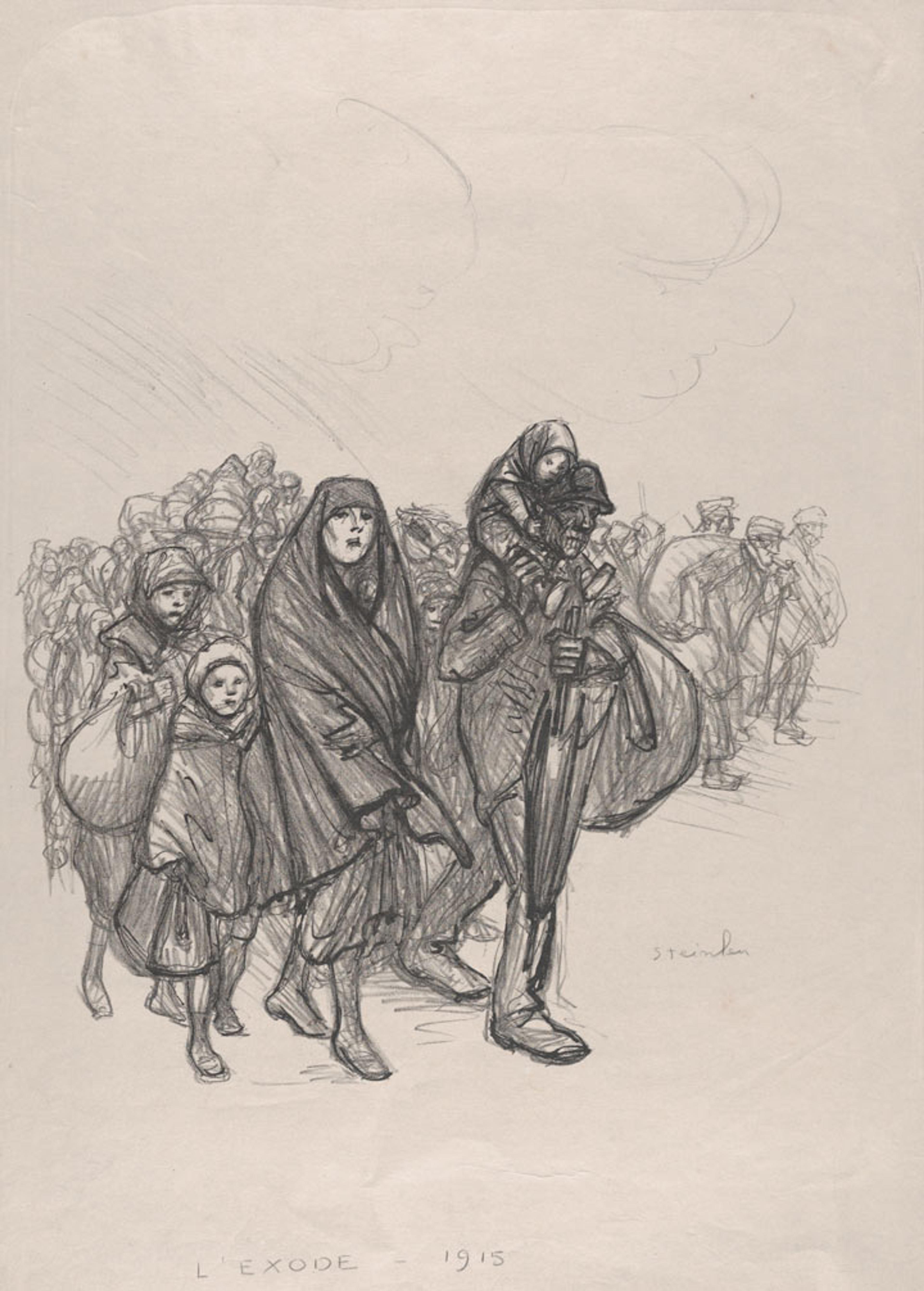

Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen (French [born Switzerland], 1859–1923). The Exodus—1915 (L'exode—1915). Lithograph, sheet: 25 11/16 x 19 13/16 in. (65.3 x 50.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Edward C. Moën, 1960 (60.593.16)

The Exodus—1915 (L'exode—1915), also called The March of the Orphans, depicts an evacuation from Belgium after a German attack. Between 1914 and 1915 nearly 200,000 refugees fled Belgium, including numerous orphaned children. This work begs close attention, not only for its visual nuances but also for its striking and regrettable resemblance to contemporary images of displaced people. A stoic mother holding an infant leads a sea of children. Individualized subjects in the foreground give way to faceless figures in the background, which Steinlen suggests with quick, sweeping lines that blend into the vast horizon. The mother's eyes fixate with strength and despondence on the distant unknown, while the children's expressions remain ambiguous and unsure against a faraway landscape.

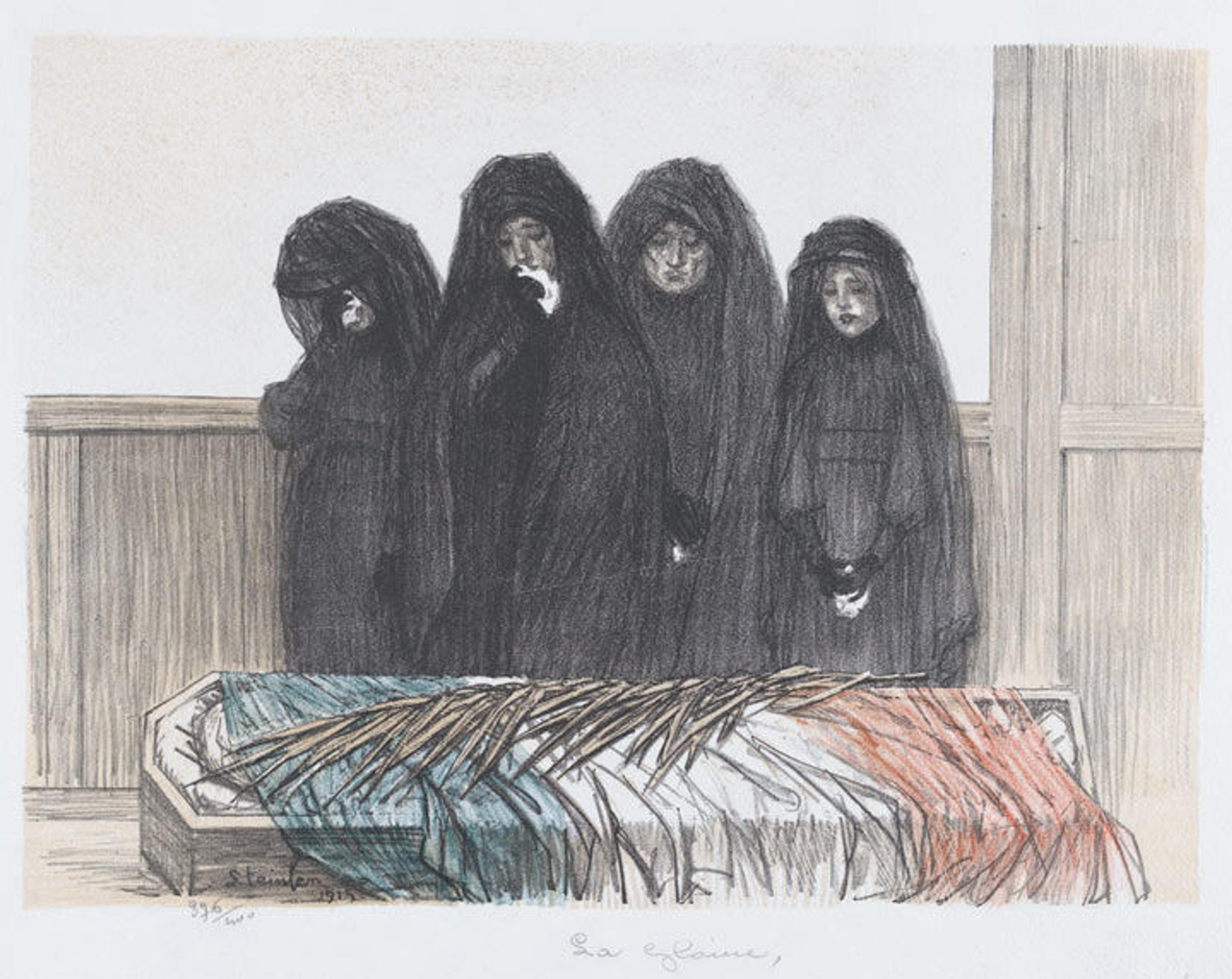

Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen (French [born Switzerland], 1859–1923). Glory (La gloire), 1915. Lithograph, Sheet: 14 3/4 x 20 7/8 in. (37.4 x 53 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Chester Dale, 1968 (68.785.6)

Steinlen, like Forain, also took to revealing the tragic contradictions of war. In one of his better-known war prints, Glory (La gloire), he depicts four women dressed in black—a mother, wife, and two sisters—mourning over the coffin of a fallen soldier adorned with a French flag and palm branch. Traditionally a symbol of victory, peace, and eternal life, the stiff palm branch seems here to echo the lifelessness of the person it honors. A rare example of color printmaking during World War I, this composition points to the loss and devastation that inevitably accompanies the "glories" of war. Both The Exodus and Glory were made using a lithographic printing technique, which involves drawing onto limestone with an oil-based medium that holds ink and is then pressed onto paper. This technique generally creates a more graphic, bold image that Steinlen may have been striving for in order to communicate this urgent sentiment.

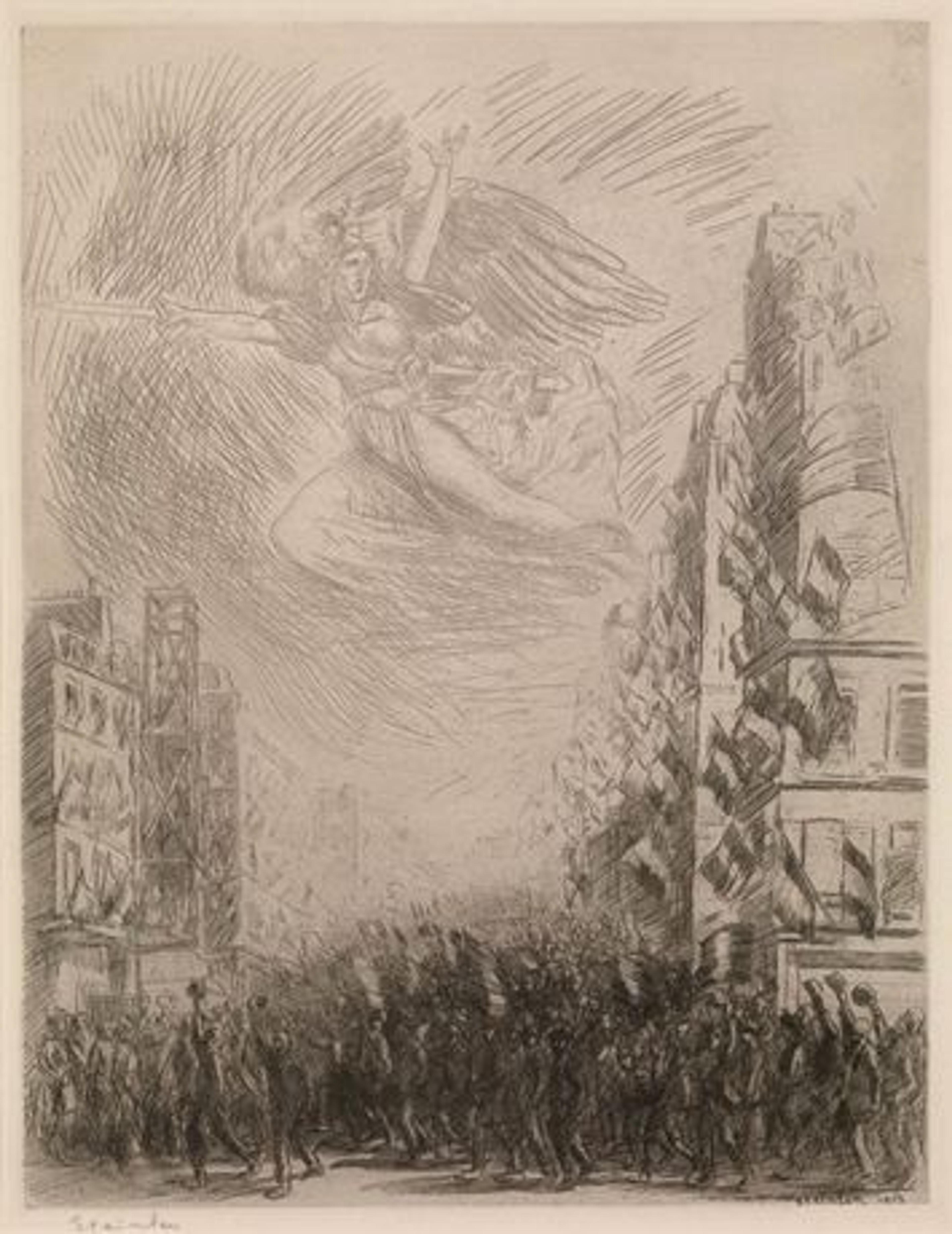

Right: Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen (French [born Switzerland], 1859–1923). Mobilization, or La Marseillaise, 1915. Etching, sheet: 25 11/16 x 19 11/16 in. (65.2 x 50 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1924 (24.58.31)

In rare instances, Steinlen appeared to engage with French patriotism—which contradicted the anti-military sentiments he asserted in the past, particularly during the Dreyfus Affair and the Panama Canal verdict. However, this seeming shift is more complex than first meets the eye, and is exemplified in his incredible virtuoso etching Mobilization, or La Marseillaise. In this detailed print, Steinlen renders the mobilization of French ground and sea troops on August 2, 1914. Anticipating Germany's invasion of France the next day, this particular moment gave rise to local patriotism, a sentiment captured in the people's gestures and the numerous French flags. Expressive lines infused with movement capture the intensity of the event, an effect likely indebted to the sketches Steinlen made from life as it unfolded.

Steinlen later translated those drawings into this etching—a process of drawing into a copper plate covered in acid-resist with a stylus, dipping the plate in acid to dissolve the areas where the lines were drawn, then inking those lines to make prints. His technique creates an incredible depth and tonality to the composition. The figure of Marianne—a symbol of the French Republic and the personification of liberty and reason—leads the charge from above. In his depiction of her, Steinlen references François Rude's 1836 sculpture La Marseillaise, created for the Arc du Triomphe in Paris. Named after the song, La Marseillaise memorializes the French Revolution and is symbolic of collective mobilization for freedom. With this in mind, Steinlen's decision to engage with this image becomes clearer; perhaps he was suggesting solidarity rather than nationalism. Interestingly, Steinlen had depicted the figures of liberty alongside the hungry in a work created before the war, explaining, "they are symbols of the crowd's solidarity in misery."

Related Link

World War I and the Visual Arts, on view at The Met Fifth Avenue through January 7, 2018