In 1911, Tiffany Studios published a pamphlet titled “Mosaic Curtain for the National Theater of Mexico City.” A mastermind of marketing and self-promotion, Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848–1933) distributed this booklet in New York City to publicize his latest tour de force, a resplendent mosaic stage curtain made entirely of Favrile glass for the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City. Work on the curtain started in 1909 and it was displayed in 1911 at the Tiffany Studios in New York with great success before being shipped to Mexico City. The Palacio de Bellas Artes, the crown jewel of President Porfirio Díaz’s dictatorship (1876–1911), had been under construction since 1904 and was meant to open in 1910 to celebrate the anniversary of Mexico’s independence. However, construction came to an abrupt halt around 1912, soon after the curtain was installed, due to the Mexican Revolution.

R.L. Stillson Co. New York (Printer) and Tiffany Studios, Mosaic curtain for the National Theater of Mexico, c. 1911. Thomas J. Watson Library, The Metropolitan Museum of Art (NA6840.M4)

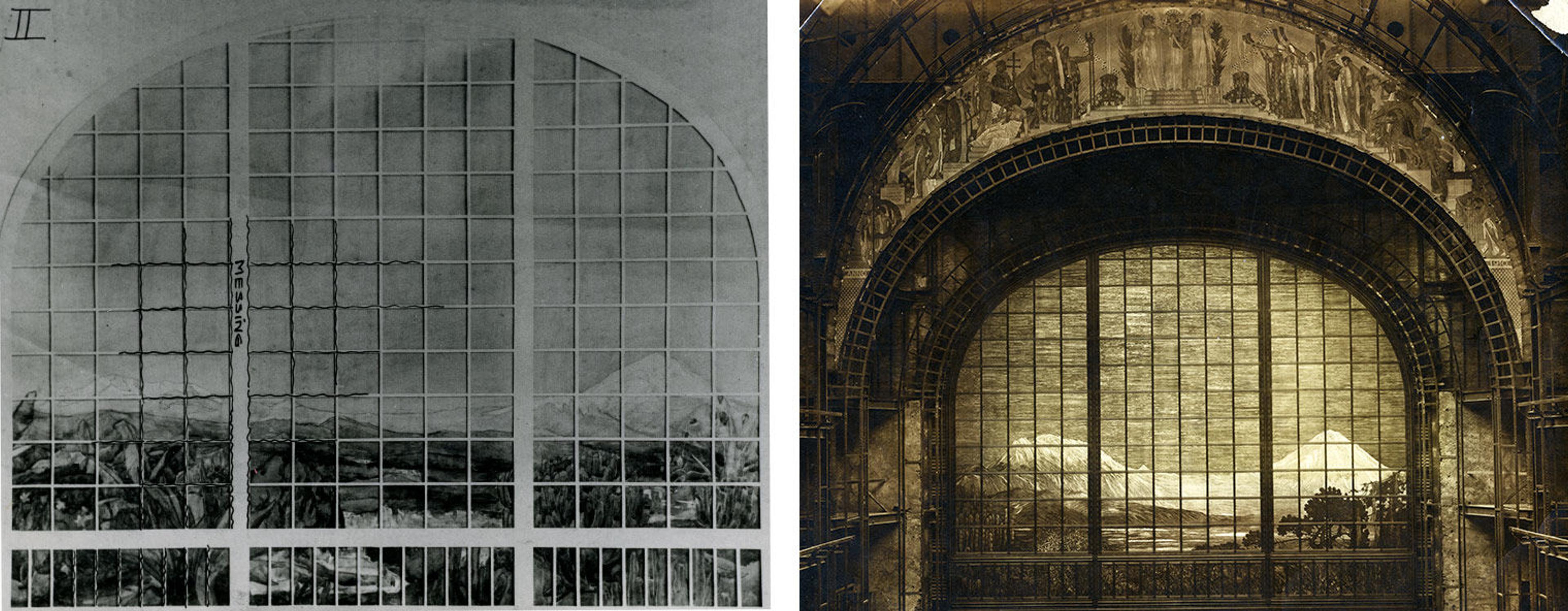

Described in the pamphlet as “a veritable poem of light,” the curtain depicts the glistening snow-capped peaks of Iztaccihuatl and Popocatepetl, two legendary volcanoes and landmarks of the Mexican panorama, rising thousands of feet into an iridescent sky. Fir trees stand out in the foreground among the variegated leaves of the bougainvillea and aralia, the delicate tones of the flowers contrasting with the giant cacti. A stream of water wends through the fertile valley at the foothills of the mountains.

Tiffany Studios, Mosaic Curtain at the Palacio de Bellas Artes, 1909–1912.

The mosaic curtain in the Palacio de Bellas Artes was hailed as a major achievement in beauty and technology, featuring an innovative hydraulic lift mechanism that works in conjunction with a sophisticated light system. It also stands out among Tiffany’s theater commissions as the only extant one, since only drawings survive of the approximately six documented theater design commissions carried out by the Studios between 1880 and 1926. These included a beautifully embroidered proscenium curtain for a New York theater that caught fire two weeks after it opened.

The construction of the Palacio de Bellas Artes started around 1905, when Italian architect Adamo Boari (1863–1928) was hired to replace the existing Mexican National Theater with a new center for the arts. Seeking a safe alternative to a textile stage curtain, Boari invited three international design houses to produce sketches for the interior decoration of the main auditorium. The reflective qualities of Tiffany’s Favrile glass were unparalleled and the firm was chosen in to execute the curtain, the biggest and most striking example of the little-known and surprisingly understudied commissions by Tiffany Studios in Latin America.

American Photo Studios and Tiffany Studios, Ballroom of the Presidential Palace in Havana, Cuba, c. 1919. The Metropolitan Museum of Art (1981.1162)

There are only a few documented examples of these Latin American commissions, but they have a few aspects in common. They were all executed between 1909 and 1920 and catered to the taste and political agenda of the countries’ elites. Both government commissions—the glass curtain for the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City and the interior decoration of the Presidential Palace in Cuba—were housed in symbolic buildings meant to represent the power of the existing regimes. Both buildings were refurnished following the ideals of the Mexican and Cuban revolutions, which happened in 1910 and 1959 respectively. Once the construction of the Palacio de Bellas Artes resumed in 1930, some of the most famous Mexican muralists such as Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco were commissioned to decorate its walls. Likewise, in 1974 Cuba’s Presidential Palace was transformed into the Museum of the Revolution, which relays the story of the fight against former President Fulgencio Batista, that last official resident of the Palace. Surprisingly, Tiffany’s masterworks were kept in these buildings despite being silent emblems of pre-revolutionary power.

Left: Tiffany Studios, Design for the central dome of the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City, 1909–1912. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 67.654.59. Right: Tiffany Studios, Design for fixtures for conservatory. Res of Mrs. Josefina de Mesa. Habana, Cuba, 1915–1916. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 67.654.29

Every year, the American Wing’s Tiffany intern has the opportunity to curate a gallery rotation. I chose to focus on the ways art has driven hemispheric connections across the Americas, and began to research Tiffany Studios’ commissions in Mexico and Cuba. Titled Louis C. Tiffany and Latin America, this installation displays two extraordinary watercolors by Tiffany Studios: one illustrates a proposed design for the central dome of the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City (ca. 1909–12); the other shows lighting designs for the residential conservatory of Mrs. Josefina de Mesa (ca. 1915–16), the owner of a sugar plantation in the affluent neighborhood of El Vedado outside of La Habana. In 1918, Tiffany also executed the interior decoration of the Presidential Palace of Havana for President Mario García Menocal and First Lady Mariana Seva y Rodriguez. The firm employed several historicizing styles for the interiors such as Empire-style mahogany furniture for the President’s study and a neoclassical ballroom that recalls Versailles. French and Oriental rugs, bronze lamp-posts, and other furnishings either made or sourced by Tiffany decorated the interior.

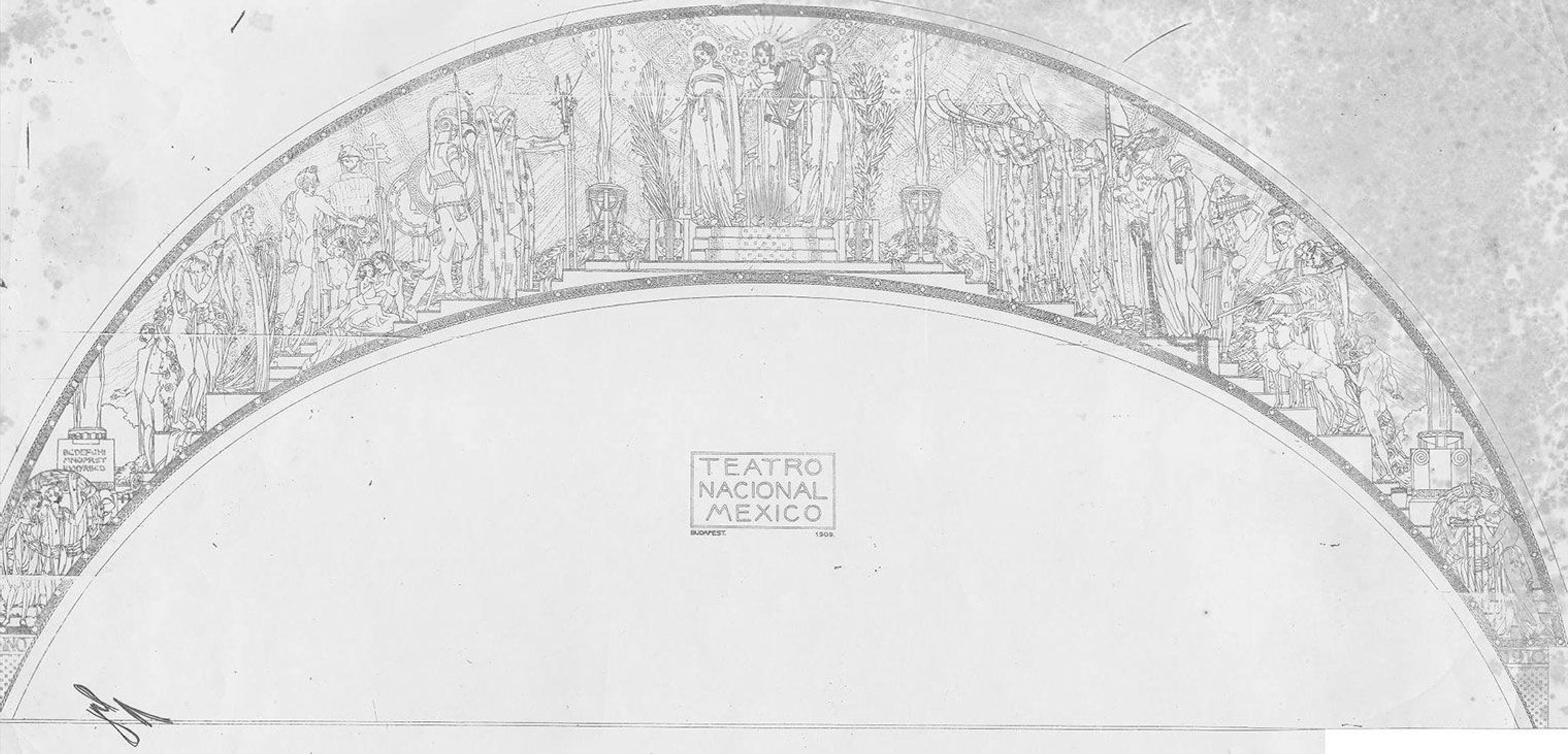

Final design for the proscenium's mural arc, 1908. Géza Maróti. Image courtesy of DACPAI - INBA.

Research for this rotation took me to Mexico City in March 2022, where I was fortunate to spend time in the Palacio de Bellas Artes’ archives and experience the grandeur of the mosaic curtain in conjunction with the theater’s famous Folkloric Ballet, an ensemble that represents the historical music and dances of Mexico. A majestic, white marble monument that serves both as performance hall and art museum, the Palacio de Bellas Artes is situated in the historic and artistic center of Mexico City, flanking the famous Alameda. While the exterior architecture illustrates the so-called Porfirian Beaux-Arts style, melding classical and Art Nouveau aesthetics, the interior decorations reflect the geometric, pyramidal shapes of both Art Deco and pre-Hispanic art. The Palacio’s archives preserves period photographs of the theater’s construction, annotated blueprints and mock-ups detailing the structure’s characteristics, and sketches of the other artworks that adorn the building, such as the mosaic proscenium arch by Hungarian artist Geza Maroti (1875–1941). A group of photos document the installation of the curtain and the evolution of its design from sketch to final product.

Left: The mosaic curtain design realized by Maróti, with his annotations above the photograph. Right: Mosaic curtain during installation. Image courtesy of DACPAI - INBA.

When I visited the Archivo General de la Nación, which houses most of the archival material related to the construction of the theater, I read through dozens of files of correspondence between Italian architect Boari and representatives from Tiffany Studios. I held the original contract that stated the conditions, deadlines, and payment agreements for the execution of the mosaic curtain. These archives allowed me to create an accurate timeline of how events unfolded in the tumultuous years leading up to the revolution. Routine documents, such as a telegraph recording the arrival of the curtain to Veracruz from New York in the steamboat “Monterrey” on June 29, 1911, infused this almost epic story with a worldly quality.

This plethora of records fleshed out a saga that, up until then, had been merely about the surface beauty of the theater curtain. The labor behind the execution, transportation, and installation of the curtain became evident in the dozens of anonymous individuals captured in the photos. Sketches and mock-ups of the masterpieces currently adorning the building revealed the arduous challenges that led to these celebrated artworks. And the copious correspondence among those involved in the construction and decoration of the Palacio elucidated how personal conflicts such as the unresolved debate of who had been the original designer of the mosaic curtain—as well as historical events like the Mexican Revolution and the First World War—fueled drama throughout the Palacio’s construction.

In March 2022, as part of her yearlong internship, the author visited the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City. Photo courtesy of the author.

Without a doubt, the pinnacle of my trip was seeing the mosaic curtain in the famed Mexican Folkloric Ballet, a show that uses the curtain’s shimmering depiction of the Mexican landscape as a prelude to the performance. Founded in 1952 by Mexican choreographer Amalia Hernández, the ballet became internationally renowned after it represented Mexico in the 1959 Pan American Games held in Chicago. The ensemble presents the most emblematic regional dances of Mexico, many of which uphold Mesoamerican traditions and reflect the multiculturality of modern Mexico. The Dance of the Matachines, Mariachi, Jarabe Tapatio, and the Charreada are some of the more than sixty choreographies performed in full costume by the ensemble.

Tiffany’s artworks in Mexico and Cuba became an entryway into the multicultural artistic environment of early twentieth-century Latin America…

As soon as the room darkened, the curtain came to life in a burst of iridescent multicolor. Percussion instruments start playing in the background as shifts in the reflected lights turn the legendary landscape in the curtain into a moving image. The cloudless skies shift from the intense reds and oranges of sunrise, to the turquoise and cerulean of daytime, and the rosy pinks and dark indigo of nightfall. The performative play between the stage lights and the glistening, colored tesserae of the mosaic curtain turned the otherwise static landscape into a ballad, an ode to the nation of Mexico.

Tiffany Studios’ commissions in Latin America is a subject ripe for further study and interpretation. In particular, the little-known projects in El Vedado, Cuba, remain obscured on account of the difficult history between the United States and the island. For me, Tiffany’s artworks in Mexico and Cuba became an entryway into the multicultural artistic environment of early twentieth-century Latin America, enriching the dull perception I had of this pre-revolutionary era. In a moment when our society craves connectedness and collaboration, what better lens to apply to our research than that which demonstrates the perpetual artistic interactions throughout the Americas.

Visit Louis C. Tiffany and Latin America in gallery 743 of the American Wing to learn more about Tiffany Studios’ commissions in Mexico City and Cuba.