The Ernst Herzfeld Papers at the Met: A Digital Resource Documenting the Study of Near Eastern Civilization

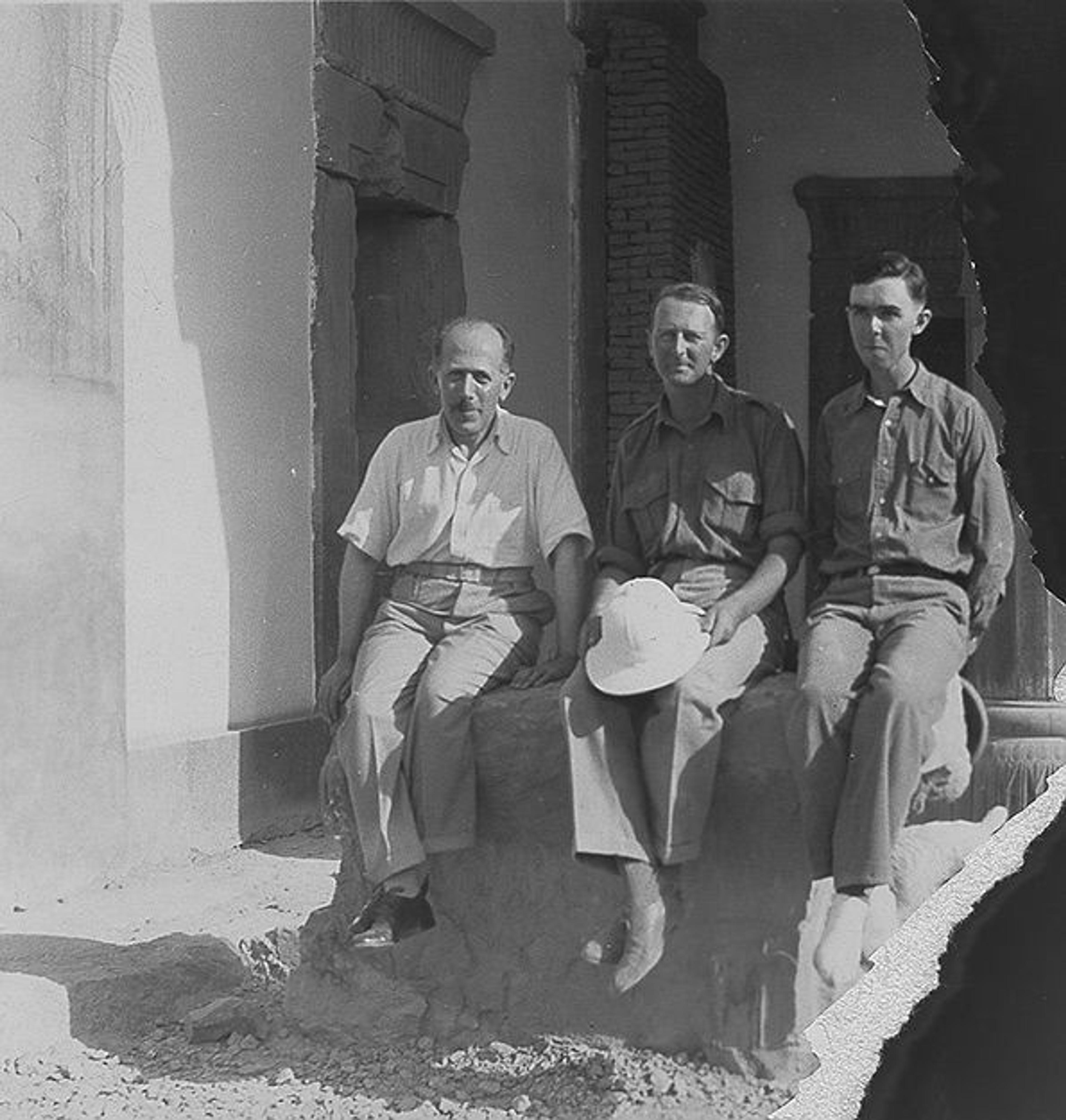

Herzfeld (left) and colleagues at Persepolis. Ernst Herzfeld Papers, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, eeh248

«It is my pleasure to introduce In Circulation readers to the Ernst Herzfeld Papers, a new resource that will be developed as part of the Digital Collections from The Metropolitan Museum of Art Libraries. Ernst Emil Herzfeld was a German archaeologist, historian, and philologist of the Near East active during the early twentieth century. The Met acquired a portion of Herzfeld's personal papers in 1943, while a larger portion went to the Smithsonian Institution and another group deposited in the Museum für Islamische Kunst, Berlin.» The Smithsonian is coming to the end of a project to digitize its portion of the archive, which will provide a wealth of information for Near Eastern studies scholars everywhere. The Department of Islamic Art at the Met is now working in collaboration with Watson Library to make the Met's portion accessible online. In late July of 2014, we launched the first series of documents from this collection—a number of architectural drawings of monuments in Syria, Iraq, Turkey and Egypt—all accessible here.

The value of the Herzfeld collection lies in its breadth, documenting numerous sites and monuments from all over the Near East, and in doing so provides a window onto a scholarly world very different from ours today. In Herzfeld's time, art historians were also photographers, draftsmen, philologists, and archaeologists, and wrote on subjects as broad and variegated as the vast region of the Near East represented in the photographs, drawings, and notes in this archive.

Herzfeld's Scholarly Career

Herzfeld was born in 1879 in Celle, Germany, but attended high school and college in Berlin. In 1903 he graduated from the Technische Hochschule zu Berlin (now the Technische Universität or TU-Berlin) with the title of Königlicher Regierungsbauführer—a technical degree in architecture that enabled him to understand architectonics, draw floor plans, and develop an appreciation for world architecture. A number of sketchbooks from Herzfeld's time as an architecture student are preserved in the archive, shedding light on the curriculum of students at the Technische Hochschule. Herzfeld simultaneously undertook studies in history and philosophy at Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität (Humboldt University of Berlin), and would later earn a doctorate in 1907 under the supervision of Eduard Meyer (1855–1930), a preeminent historian of the ancient world.

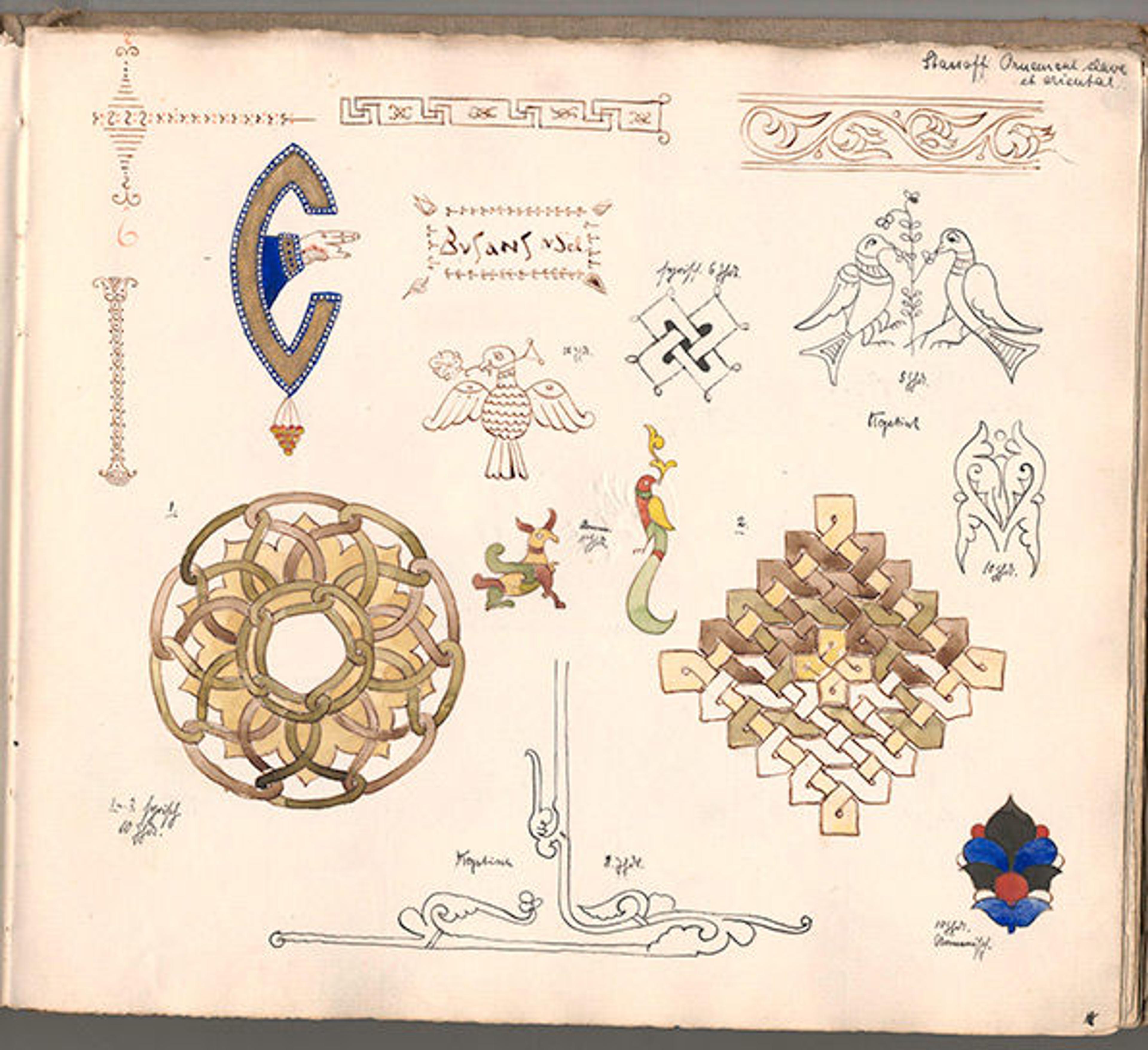

This sketchbook page, made circa 1902 as part of a course taken by Herzfeld at the Technische Hochschule zu Berlin, shows various "Byzantine" and "Coptic" ornaments copied from a textbook. Ernst Herzfeld Papers, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, eeh1689

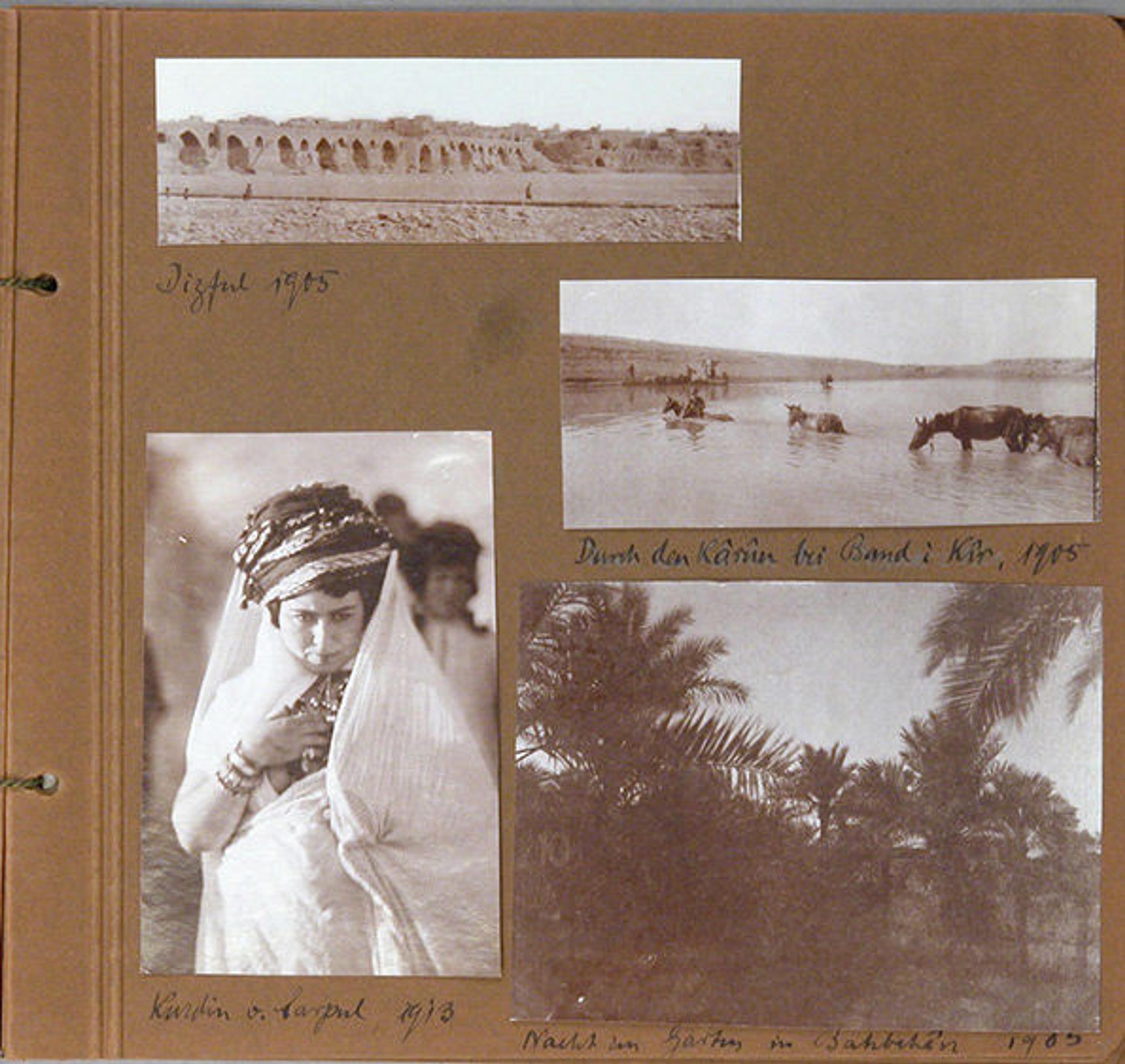

Soon after graduating from college, Herzfeld went to Iraq where he served as an assistant to Walter Andrae (1875–1956) in the German Archaeological Institute's excavations at Assur. This experience must have been formative for the young scholar, because Herzfeld was to spend much of his professional career in the Near East from this point on. After finishing his doctorate, he conducted extensive field research on architecture in Mesopotamia and Syria-Palestine between 1907 and 1914. During World War I, he returned to the Middle East where he served as a surveyor in the German army. In the 1920s, he relocated semipermanently to Iran to conduct fieldwork and advise the government on its antiquities legislation. Although he was appointed associate professor of Near Eastern geography and art history in Berlin in 1917, he was more at home in the Near East, as his many photographs from the region attest.

Herzfeld traveled far and wide in the Near East, documenting the people and places he saw. This page from a photograph album shows a Kurdish woman and various landscapes in Kurdistan (present-day Iraq and Iran). Ernst Herzfeld Papers, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, eeh591

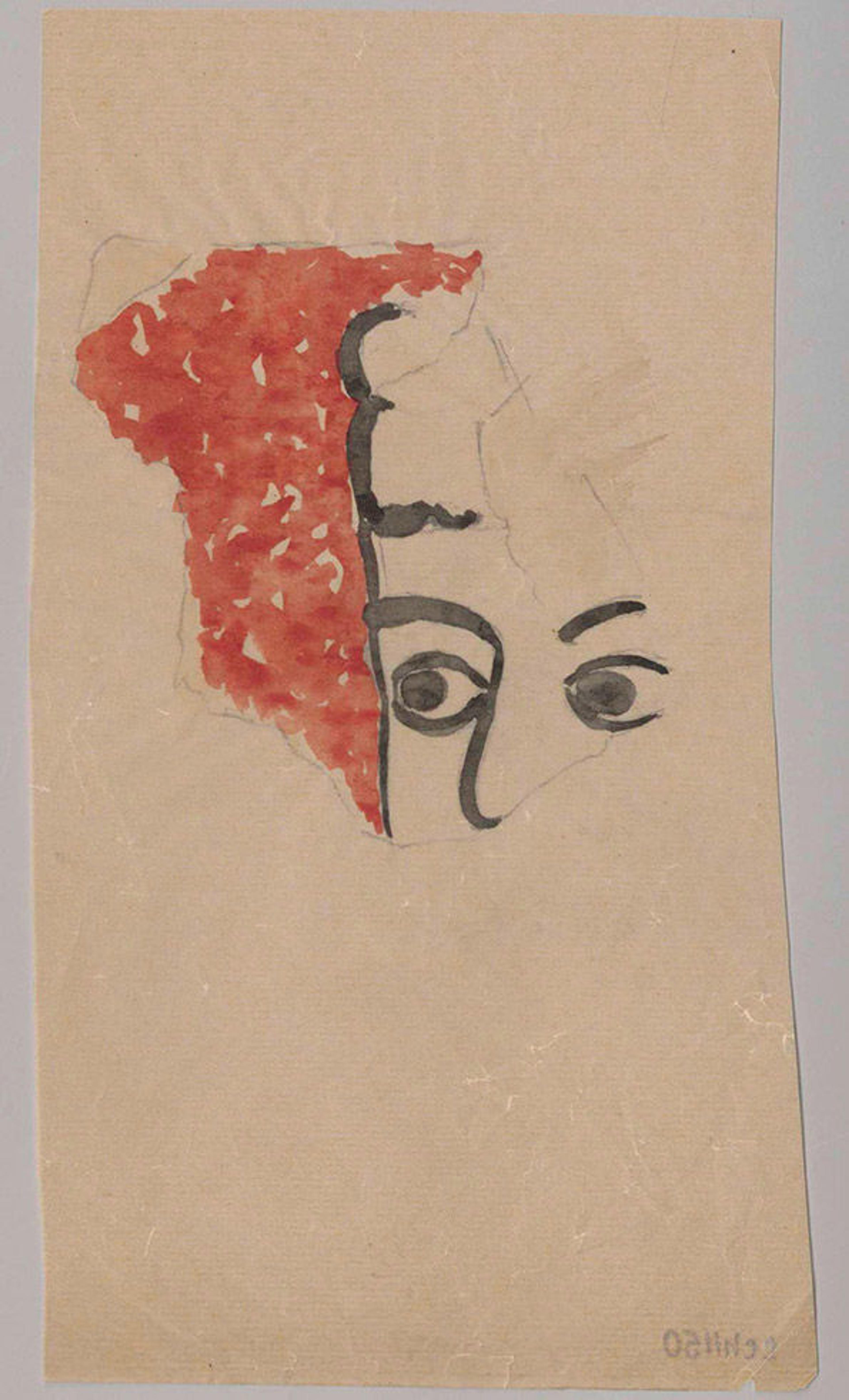

Herzfeld's research is too vast to summarize here: an author search on Watsonline returns thirty-seven books that give an idea of its breadth and depth. The expansive nature of his work is underlined by the fact that Herzfeld is still considered foundational to two different fields of scholarship today. Among historians of Islamic art, Herzfeld is celebrated for his excavation of Samarra, an archaeological site on the Tigris some one hundred kilometers north of Baghdad. Samarra served as the capital of the Abbasid Empire (a.d. 750–1258) for approximately fifty years, and its ruins represent the largest source of archaeological data we have on Abbasid art and architecture. Herzfeld spent two seasons, from 1911 to 1913, excavating Samarra's palaces and private houses, unearthing numerous examples of stucco wall panels, fragments of wall paintings, and pieces of pottery and glass.

Herzfeld published most of the Samarra finds in a six-volume series titled Die Ausgrabungen von Samarra. The Met's Herzfeld Papers include nearly a complete set of watercolors and drawings for the first and third volumes of this series, Der Wandschmuck der Bauten von Samarra und seine Ornamentik (Berlin, 1923) and Die Malereien von Samarra (Berlin, 1927). Consisting of over six hundred items, this series of drawings allows us to see Herzfeld's process in processing his finds for publication.

This watercolor depicts a fragment of a wall painting Herzfeld found in the Main Caliphal Palace of Samarra. This and other watercolors were eventually published in his catalogue of Samarra paintings, Die Malereien von Samarra (Berlin, 1927). Ernst Herzfeld Papers, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, eeh1150

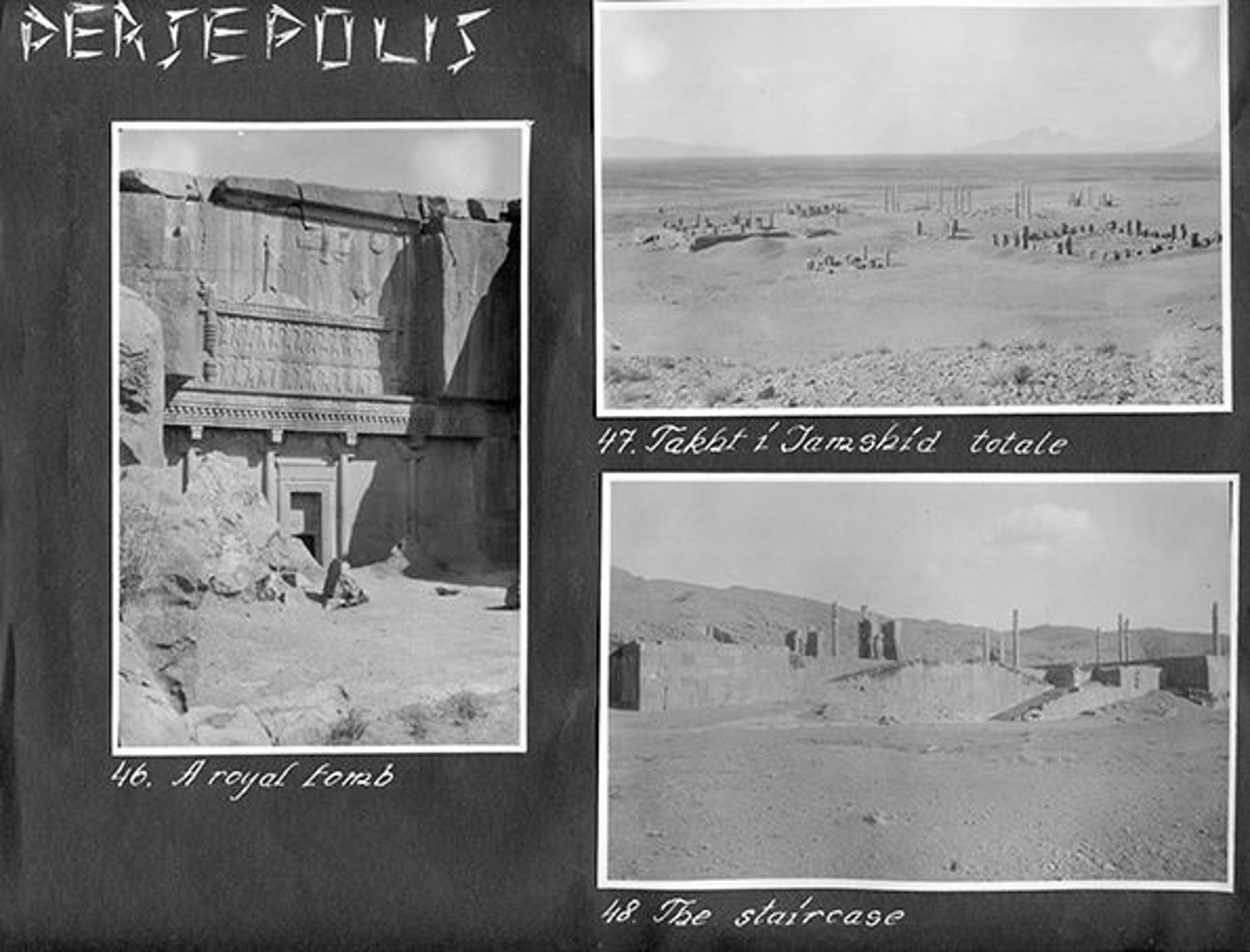

Herzfeld is equally lauded in the field of ancient Near Eastern art and archaeology. Most notably, he conducted excavations at the Achaeminid sites of Pasargadae and Persepolis, both located in Iran. Herzfeld's excavations at Persepolis were undertaken from 1930–34 as part of a project administered by the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago. Among the most significant findings of the Persepolis campaign was the discovery of the Eastern Stairway of the Apadana (columned audience hall) of Darius and Xerxes, which included bas-relief friezes depicting a procession of delegates bringing tribute to the Achaeminid ruler.

Photograph album showing scenes from Persepolis. Ernst Herzfeld Papers, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, eeh999

Herzfeld's activities in the Near East may well have continued for years but for the unfortunate events of the 1930s. Life in Germany was rapidly declining under the hegemony of the Nazi party, and the country's diplomatic relationships with Iran suffered as well. In 1935 Herzfeld was forced into early retirement from his professorial post because of Jewish descent, and he immigrated to the United Kingdom and then to the United States in 1936. In the U.S. he continued to write and deliver lectures and served as a fellow at the Institute of Advanced Studies, Princeton, until his retirement in 1944.

Not long after his retirement, Herzfeld fell ill. He died in Basel, Switzerland, in 1948, at the age of sixty-eight.

Herzfeld at the Met

Fortunately for the scholarly community, Herzfeld saved many of his records. When he moved to the United States, he brought with him a collection of photographs, sketchbooks, notebooks, and drawings that together formed a substantial archive documenting people, places, and artifacts from all corners of the Near East. Some of the material relates closely to his publications, but other portions were never published.

While at Princeton, Herzfeld communicated regularly with Maurice Dimand (1892–1986), who was then a full curator in the Department of Near Eastern Art at the Metropolitan Museum. When Herzfeld retired, he offered to sell the Met part of his archive, and the Board of Trustees authorized its acquisition in 1943. The material was to include some four thousand books from Herzfeld's library along with several thousand original drawings and watercolors, photographs, sketchbooks, and notebooks. Around the same time, Herzfeld donated an even larger portion of his archive to the Smithsonian Institution that remains in the archives of the Freer and Sackler Galleries today. For more on the Met's acquisition of its portion of the Herzfeld archive, see Rebecca Lindsey's essay in the finding aid for the Met's Herzfeld Papers.

The material received by the Met was initially divided between two departments: the books were sent to Watson Library while the archival material went to the Department of Near Eastern Art. In 1963, however, the archival material was further split with the division of that department into the Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art and the Department of Islamic Art.

A number of Herzfeld's books were eventually deaccessioned from the library, but those that still remain can often be identified by Herzfeld's personal book plate, which features a drawing of the spiral minaret of the Congregational Mosque of Mutawakkil at Samarra. Some books also bear the impression of his personalized stamp, reading "Dr. Ernst Herzfeld Photo" in square Kufic script.

Front cover of Herzfeld's copy of Baghdad during the Abbasid Caliphate, a classic work on the historical topography of Baghdad by Guy Le Strange (Oxford, 1900). One can see Herzfeld's personal bookplate and the impression of his stamp faintly next to the upper right-hand corner of the plate.

Some of Herzfeld's books lack the ex libris but have inscriptions that identify the book as coming from his collection. One intriguing example is a volume combining two reports published by the French architect Henri Viollet, who made excavations at Samarra just before Herzfeld. In this book, we have evidence of direct exchange between the two scholars who were initially at odds over Samarra. The title page has a personalized note from Viollet to Herzfeld dated 1910.

Front page to Herzfeld's copy of H. Viollet, Description du Palais de Al-Moutasim, fils d'Haroun-al-Raschid à Samara (Paris, 1909), inscribed by the author: "à monsieur E. Herzfeld. Hommage et cordial souvenir. Viollet"

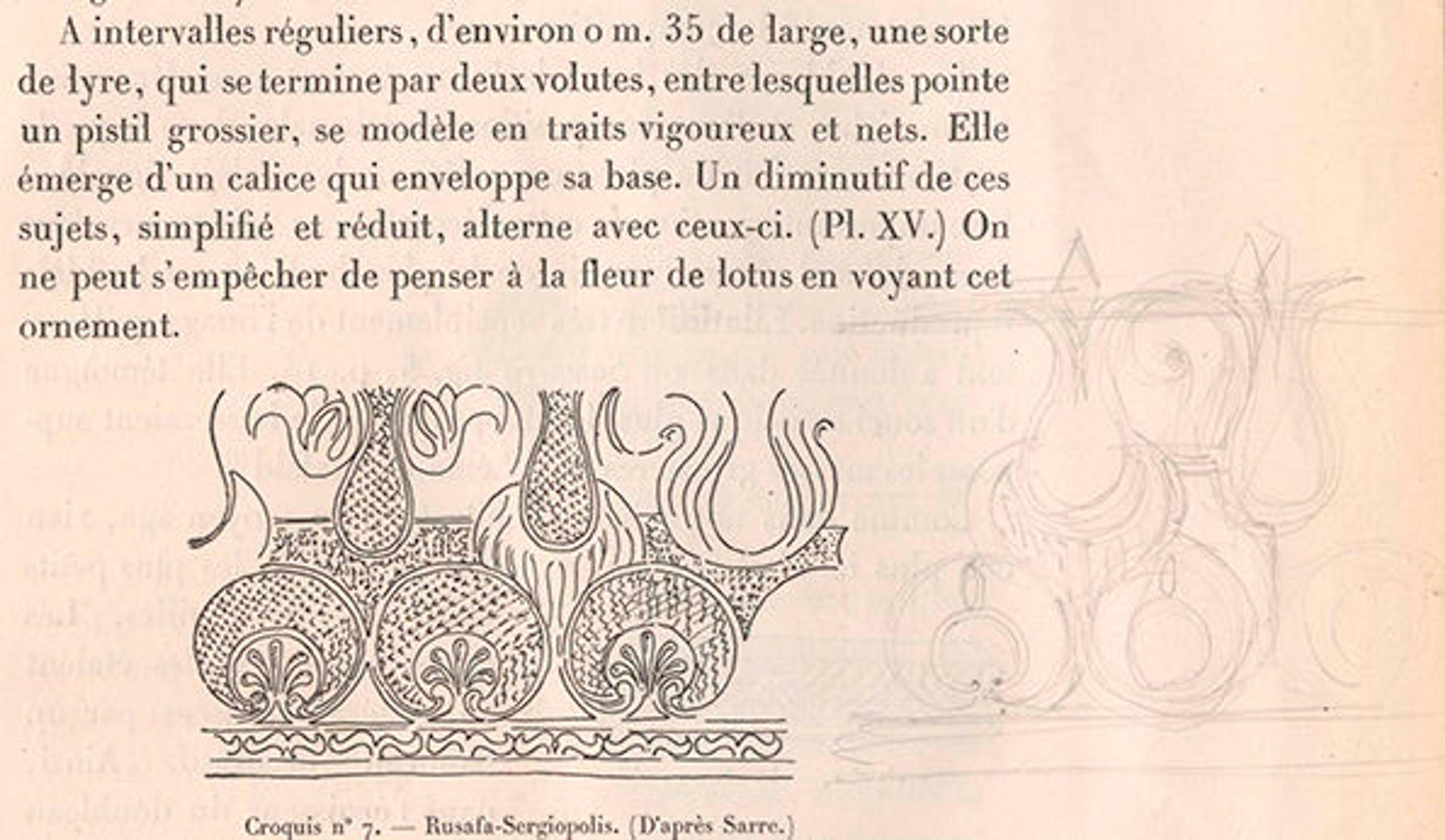

And lest any future readers in Watson Library get confused about the nature of early Islamic vegetal ornament, Herzfeld also made corrections to several of Viollet's reconstructions (in pencil, at least!).

Falsch! Herzfeld's corrections to Viollet's reconstructions of a frieze at Rusafa (Syria)

The materials housed in the two curatorial departments have seen some activity since their acquisition and division. In 1976 Margaret Cool Root numbered and inventoried the items housed in Ancient Near Eastern Art and published a summary of her work in the Metropolitan Museum Journal. Additionally a number of documents in the Department of Islamic Art were featured in a 2002 exhibition entitled Herzfeld in Samarra. In conjunction with this show, the Islamic material received conservation treatment and Rebecca Lindsey, a member of the department's visiting committee, devised a numbering system for the documents and began the process of cataloguing and scanning them.

Over the next two years, the Department of Islamic Art will finish cataloguing and digitizing its portion of the Herzfeld Papers. It is a big project, but thanks to the combined efforts of staff in Archives (James Moske), Digital Media (Cristina Linclau), and Watson Library (Dan Lipcan and Robyn Fleming), there is now a system in place to work through the material and make the jump from archives box to online collection. A number of summer interns have also been very helpful in the digitization process (Charmaine Branch, Ilana Grady, and Claire Elias).

Certain uses of the Herzfeld Papers are predictable and offer an immediate rationale for their digitization: unprocessed excavation notes or photographs of buildings whose forms have changed might provide scholars with new information on old sites. Similarly, seeing the process through which Herzfeld published his findings could shed light on assumptions he made that future historians may wish to rethink. The beauty of archival collections like the Herzfeld Papers, however, lies in their touching on a variety of subjects through a number of different media, and as such, one cannot fully predict what fascinating connections they may provide for future research.

Bibliography

Gunter, Ann C. and Stefan R. Hauser, eds. Ernst Herzfeld and the Development of Near Eastern Studies, 1900–1950. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2005.

Hauser, Stefan R., David Stronach, Hubertus von Gall, Prods Oktor Skjærvø, and Josef Wiesehöfer. "Herzfeld." Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XII, Fasc. 3: 290–302. New York: Encyclopaedia Iranica Foundation, 2004. http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/herzfeld-ernst.

Lindsey, Rebecca. "Introducing the Ernst Herzfeld Papers in the Metropolitan Museum, Department of Islamic Art." Published May 31, 2013. Accessed September 24, 2014. http://samarrafindsproject.blogspot.com/2013/05/introducing-ernst-herzfeld-papers-in_31.html.

Root, Margaret Cool. "The Herzfeld Archive of the Metropolitan Museum of Art." Metropolitan Museum Journal, Vol. 11 (1976): 119–124.

Upton, Joseph. Catalogue of the Herzfeld Archive. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1974.

Matt Saba

Matt Saba is the Mellon Curatorial Fellow in the Department of Islamic Art.